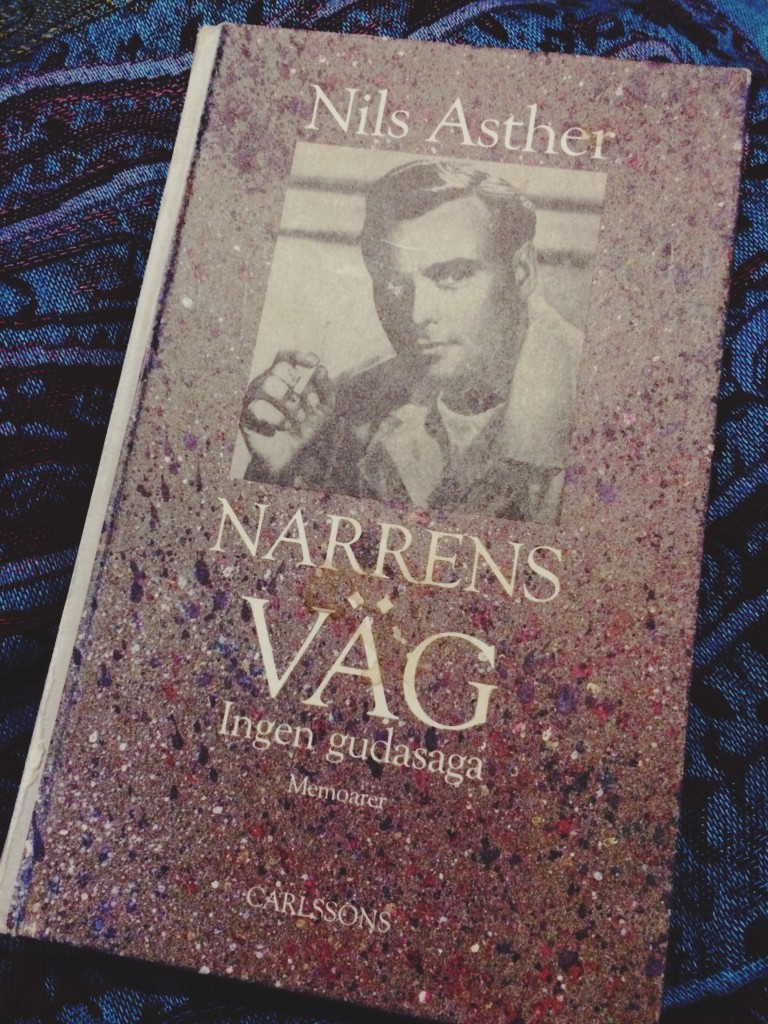

Hej! Välkommen till min blogg. I’ve been haltingly translating movie star Nils Asther’s memoirs from Swedish, because who needs a social life, really? The fact that I understand only extremely basic Swedish hasn’t stopped me, as I’ve been going page-by-page with the surprisingly good Scan&Translate Pro app and the help of a few very patient Swedish friends.

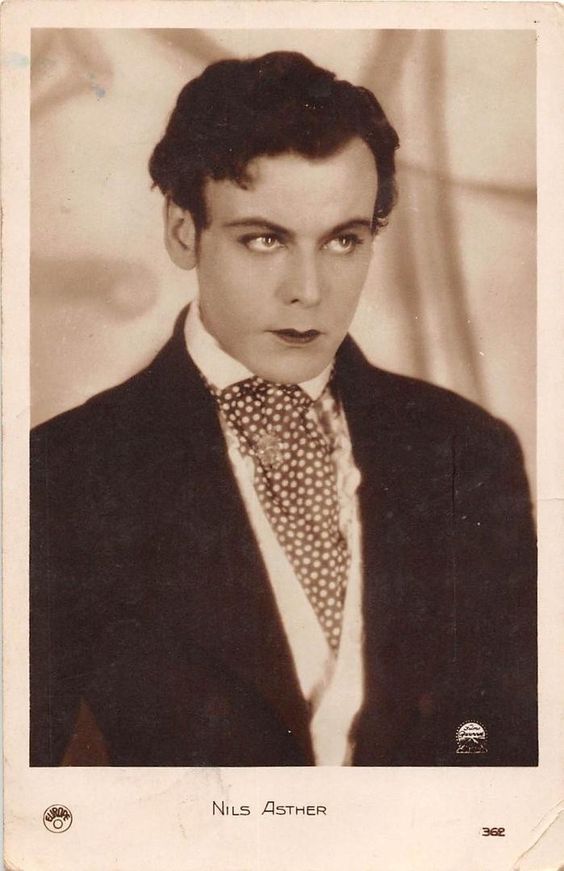

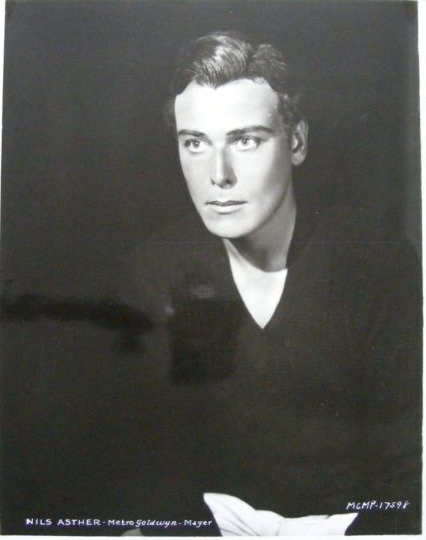

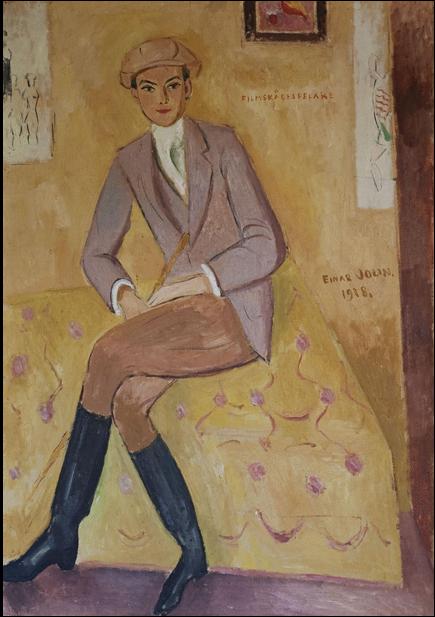

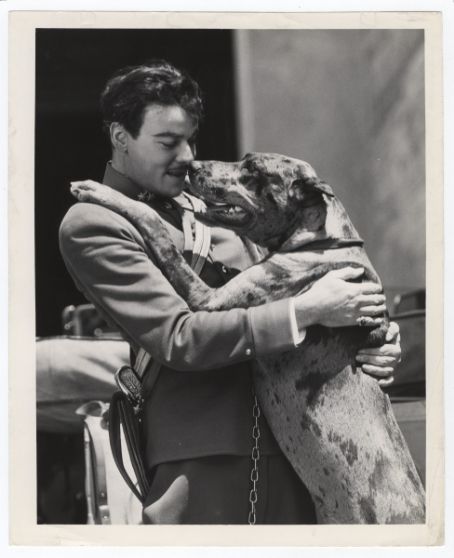

When we last saw the lovely Nils, he’d been having a gay old time in Hollywood. Though the roles required little more than standing around looking gorgeous, the money was pouring in, the fan mail was piling up, and the press adored his mysterious, intellectual, possibly-an-aristocrat-or-a-spy-who-cares-which persona. It was shallow and dumb, and as much as he sneered at it, it was fun.

When we last saw the lovely Nils, he’d been having a gay old time in Hollywood. Though the roles required little more than standing around looking gorgeous, the money was pouring in, the fan mail was piling up, and the press adored his mysterious, intellectual, possibly-an-aristocrat-or-a-spy-who-cares-which persona. It was shallow and dumb, and as much as he sneered at it, it was fun.

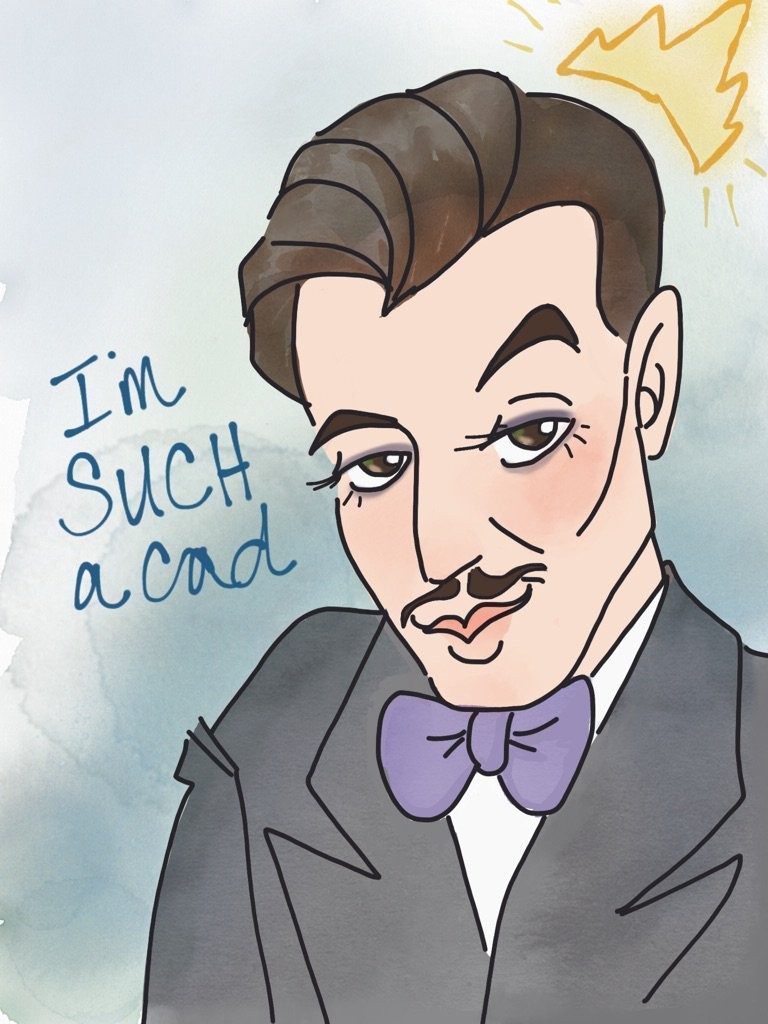

Enter Eddie Mannix, Hollywood fixer and all-round sentient turd. ‘A thug in a suit’, Mannix cleaned up the messes stars left behind: rapes, murders, suicides, and everything in between. If you were a 1930s Hollywood luminary and you’d just found a body in your swimming pool, you called Mannix, not the police. Mannix ran with the Mob, and he had a hand in more than a few suspicious deaths, including his own wife’s. He controlled press, police and coroners alike. If you defied him, you not only risked your career, but your neck.

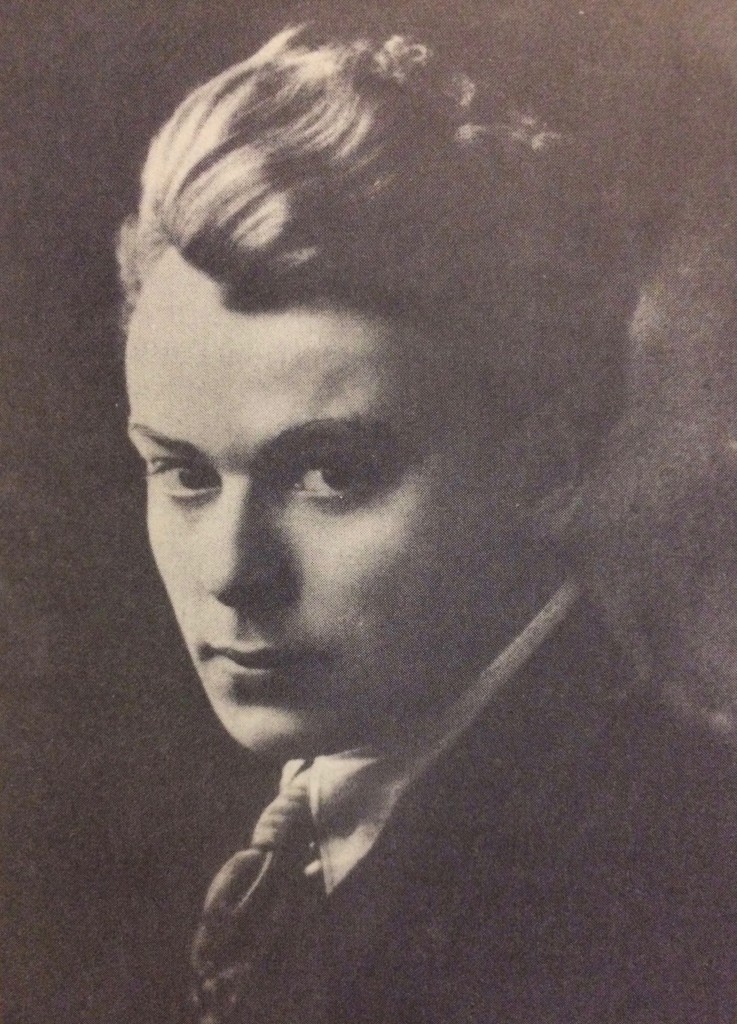

Is this the face of a man with a soul? Nay. Nay and fie.

Part of Mannix’s job was to conceal the private lives of homosexual stars. During the 1920s, attitudes were more liberal within Hollywood, but as the thirties moved in, once successful and beloved figures began to disappear. Ferociously bisexual Nils was being watched.

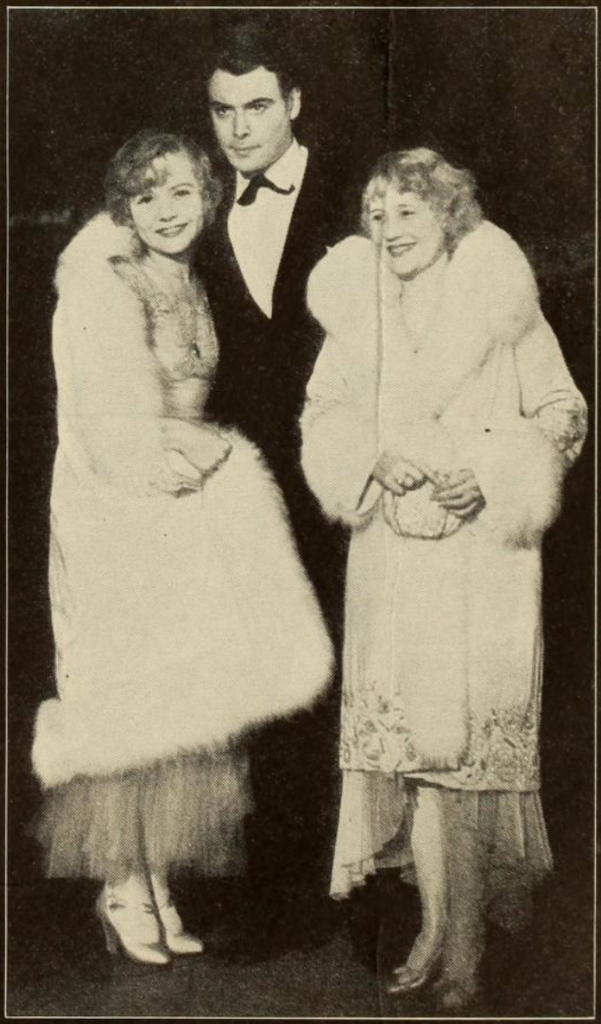

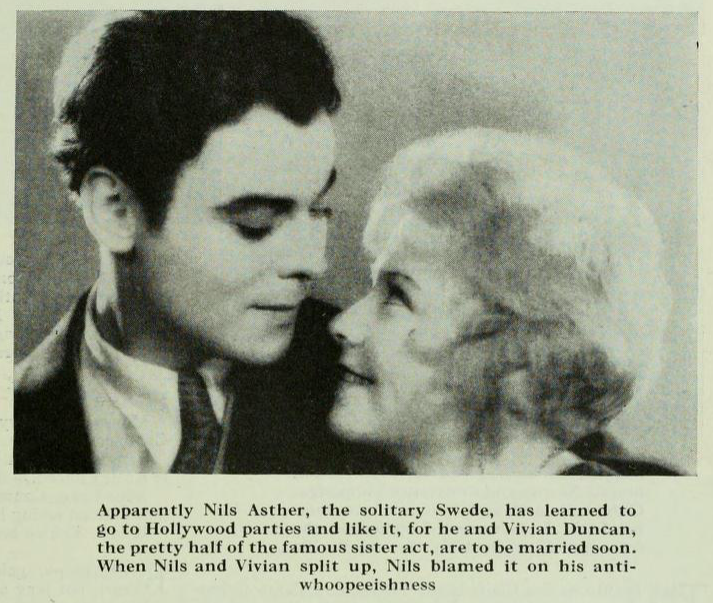

Mannix was tasked with marrying Nils off. Early in his career, Nils had been in an Uncle Tom’s Cabin spinoff, Topsy and Eva, starring the vaudeville twins Vivian and Rosetta Duncan. The twins were wildly popular, but there was a snag – Rosetta was a known lesbian. The neat fix would be to hitch her to Nils, but Rosetta was not considered a beauty. The next best thing was Vivian. Tiny, blonde, and dimpled, Rosetta’s pretty twin would dispel the aura of scandal around the Duncans as well as their mysterious one-time co-star. If it was good enough for Mannix, it was good enough for the studio – if the actors complied.

If.

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

The studio responded by withholding roles. Fine, Nils said. He had enough money saved to support himself for years. He could open a grocery store if he felt like it. But going without work drove him slowly crazy. He found himself lying around, sketching self-harm fantasies all day. If he could disfigure himself, he thought, the studio would leave him alone.

But Nils was terrible with money. Having enjoyed the attentions of sugar daddies for so long, he took his attitude from The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (which was incidentally one of his aliases): live life to the full and have no regrets. Which is fine, unless you’re living right after the great stock market crash of 1929. Nils’ savings bank was one of dozens who folded, losing him over $30,000. Without work, there was no way he could support himself in any meaningful sense. Mannix simply had to wait for who would blink first.

It was during this strange standoff that Louis B. Mayer paid for a spell in an upmarket psychiatric clinic for reasons Nils was not willing to write about. One wonders if it was one of the early twentieth century’s gay ‘cures’. Whatever it was, he came out just as depressed as ever. Might as well marry.

Before his wedding, Nils went on one last romantic retreat with Greta Garbo. Garbo was bisexual but discreet, so Mannix was happy to treat her with fond tolerance. They walked through the woods together by moonlight. For the third time, he expressed his deep regard for her. Perhaps as an official couple they could find some sort of happiness, or, more importantly, freedom – intellectual and artistic. But it wouldn’t work. Greta’s own marketing shtick was aloneness. When he took himself off to bed alone, saddened and silent, she crept in and gave him a cuddle. Soon they were giggling again like old comrades, but the situation was bleak. They both knew they were at the mercy of Mannix.

Vivian Duncan wasn’t having fun either. In public, her ex-boyfriend Rex Lease punched her in the face. The open secret of lavender marriage carried a stigma akin to prostitution. She had tried to get to know Nils – he taught her to ride horses, she dragged him to parties he hated – but they were fundamentally clashing personalities.

They married in Reno.

Garbo found the whole thing grimly hilarious. “You don’t even know which one you’re married to, do you?”

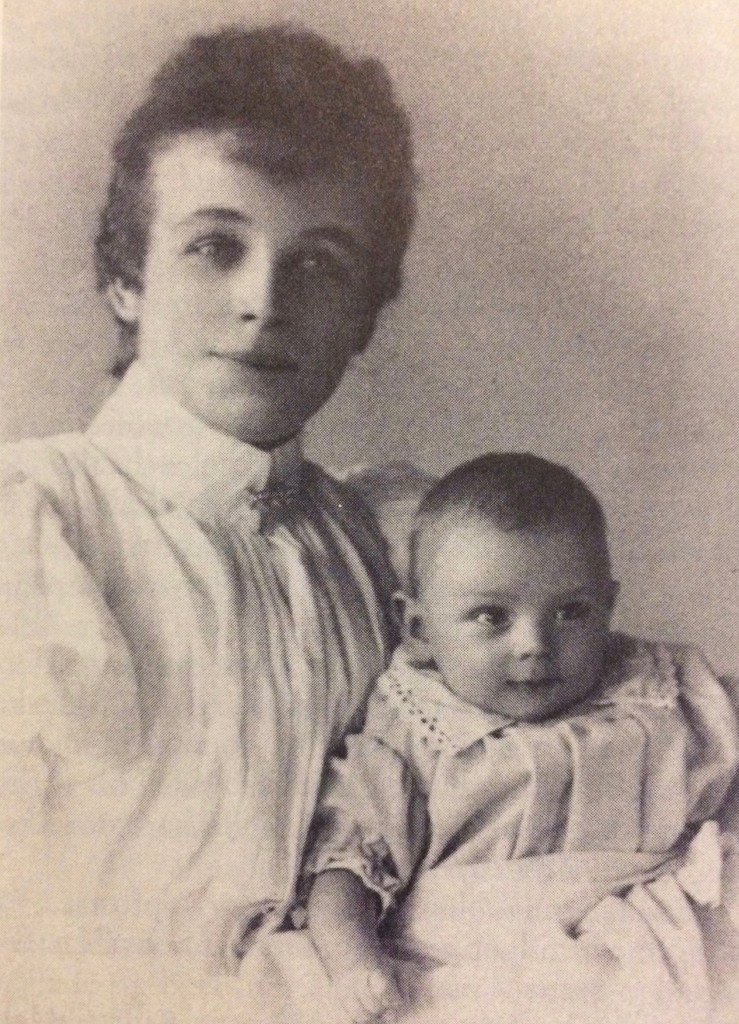

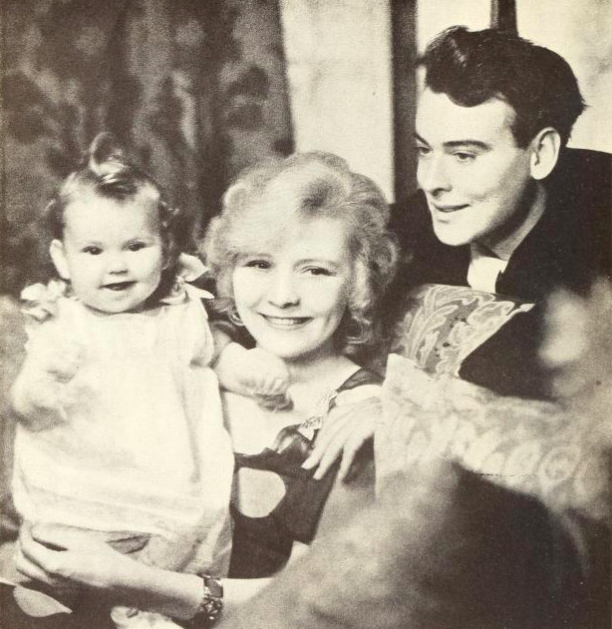

Then in 1931, to the studio’s relief, along came a beautiful baby. No one could deny who her father was.

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

Little Evelyn grew up to raise guide dogs and horses in California. As a child, she was wheeled out as ‘The International Baby’, singing in vaudeville skits with her mum and aunt. It looks like she had no relationship with her father. In his autobiography he simply says “we had a child”. That’s it. Of Vivian he said “she only married me for the money”. He never mentions either of them again.

Having done his part by spawning an infant, Nils was no longer keeping up any pretence of being happy, stable or straight. The press were fed quotes about him adoring his vivacious wife while loathing the media’s interference. “It cheapens our love,” said someone who sounds nothing like Nils. “I love her still, and yet…I am a bad character…”

Okay, that last bit does sound like him.

By 1933, pretty boys were going out of style. Leading men needed to be ‘rugged’, ie) straight-coded, and Nils’ refusal to hide his dalliances with men rankled the wrong people. Eddie Mannix gave the press the go-ahead to drop unsubtle hints about Nils’ private life. Why did he not live with his beautiful wife? What secret was he hiding? All the gossip columnists knew what that meant. They’d rooted out queers before, here was the latest.

The punishment continued. The studio passed him over for all but the lousiest roles (fighting a mutant sting ray – a mutant sting ray – being one of them), forcing him to go on a vaudeville tour with the Duncans out of sheer poverty.

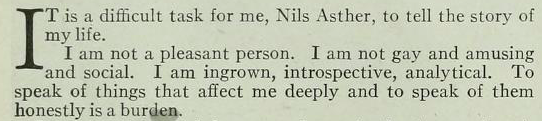

“But I am not mysterious,” he protested in Screenland Magazine. “I have not a secret in the world. I come, I do my work, go home. I have my friends. I never hide anything I do. I think people make up things to guess about me, then say I am mysterious when it is a really they. I am just a young Swede trying to get along.”

“But I am not mysterious,” he protested in Screenland Magazine. “I have not a secret in the world. I come, I do my work, go home. I have my friends. I never hide anything I do. I think people make up things to guess about me, then say I am mysterious when it is a really they. I am just a young Swede trying to get along.”

By the end of 1933, he all but vanishes from the movie magazines that once praised his every move. He was blacklisted for ‘breaking contract’, ‘unacceptable foreign accent’, and ‘visa problems’ variously. He and Vivian divorced.

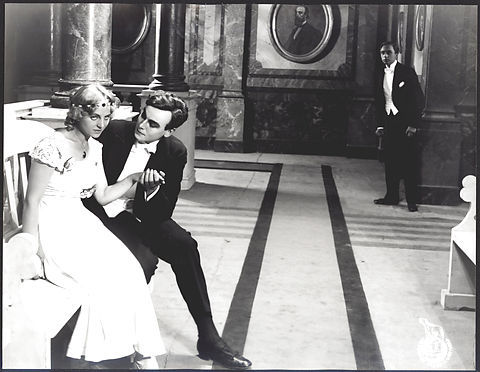

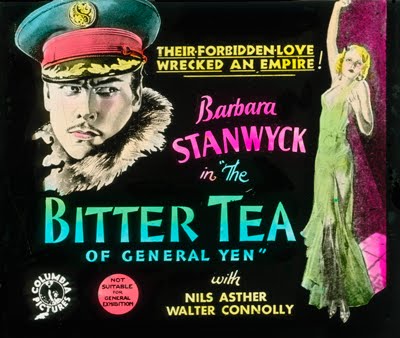

And then General Yen happened.

(If you don’t already know the film, here’s an advance warning for yellowface.)

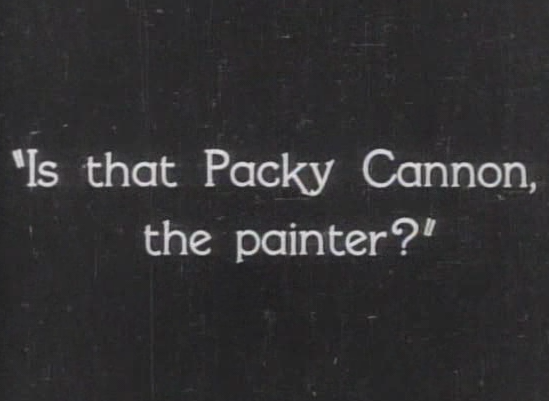

Their forbidden love wrecked an Empire! Frank Capra had a vision. A love story like no other, smashing taboos and shaking up the audience as much as the characters. War, sex, religion, race, and downright double-crossing peril. There was one problem. Cinematic code of the time meant you couldn’t depict a love story between two people of different races. However – there was a loophole. The rule only stipulated actors, not characters. An interracial love story was permitted so long as both actors were white.

Capra wanted a tall, imposing Chinese actor to play the General, but that wasn’t possible. In Nils’ tranquil disposition, Capra said he could see the wisdom of an ancient empire. (Steady on, Frank). As for the rest, Nils already had slightly slanted eyes and high cheekbones, so the makeup artists only had to enhance these features*. There’s a short documentary showing the transformation here. They trimmed his long eyelashes, resulting in painful surface burns from the studio lights. He was in real danger of losing his sight, but he never complained. He was just pleased to be doing something that didn’t involve a mutant sting ray.

Yes, it’s uncomfortable to watch. Though they did their best to avoid the grotesque charactures that had come before – and there were many – it’s still yellowface. Barbara Stanwyck’s character, a respectable Christian missionary, realises she holds deeply racist beliefs incompatible with her faith. Worse, she – a married woman – is in love with a foreign warlord. Instead of fighting her attraction, she accepts it, returning to her life among white people changed, disturbed, bereft. Yen himself is charming, cultured, and challenges his leading lady on her hypocrisy. Capra expected an Oscar for what he saw as his magnum opus, but it wasn’t to be. Can love survive such ground-in prejudice? A significant portion of the audience couldn’t care less. Complaints came rolling in.

Young women, however, were into it. The press silence was broken by letters demanding to know when they would see Mr Asther again. Interviews followed, some openly accusing the Duncan sisters of blowing their chances with this ideal piece of husband material. It was their fault he’d disappeared from public life.

He seemed so healthy, so happy, so pleased to chat, said reporters. Was he in love?

Nils smirked.

You need to remember that smirk. Because so did Eddie Mannix.

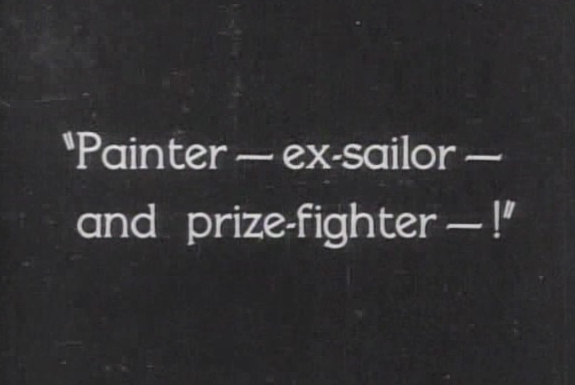

* Quick note: Nils actually claimed he came up with the makeup techniques for General Yen. Take it with as big a pinch of salt as you wish, but he wrote how he’d spend his days off in Chinatown, making sketches of his acquaintances there. Then, at home, he’d try to modify his eyelids in a more realistic manner than Hollywood’s usual ‘just tape them up, who cares’ method.

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.

Braham, John, Esq.

Braham, John, Esq.