I’ve been translating Nils Asther’s memoir from Swedish because I apparently have nothing better to do. Catch part one here.

It’s fair to wonder what would have happened to Nils Asther had he not attracted the attention of Mauritz Stiller that evening. The teen had no money, no qualifications, no home to go to, and in his mind at least, no family.

Stiller was born in Helsinki in 1883, and fled to Sweden to avoid being drafted into Czar Nicholas II’s army. He was a pioneer of silent films, writing and directing more than thirty-five features in his lifetime. The night he laid eyes on Nils, Stiller was eating out with a fellow screenwriter, Sam Ask. Stiller ushered Nils and his companion over to Ask. “Doesn’t this one look like an actor?”

(Nils’ friend was ignored for the rest of the evening. Poor boy, he was lovely, but he had a face like the back of a tram.)

Soon they were joined by a hefty gentleman with thick curly hair. He looked out of place in the noisy eatery, standoffish and over-eager at the same time. This was Hjalmar Bergman, a respected author. Having established himself as highly literary and intellectual, the death of his father brought about huge debt, and Bergman was forced to write more crowd-pleasing works. This required research, such as drinking, snorting cocaine, and fraternising with gorgeous young men.

Tonight was Bergman’s lucky night.

“He looked at me as if I were an angel fallen from the skies,” Nils wrote. “It took a while before he sobered up. He asked me my name and what I did. I told him that I was kicked out of my adoptive parents’ house and from the Spyken school in Lund. Now I had decided to become an artist. Hjalmar Bergman reacted negatively. Not many artists could live on their jobs. Such fancies! Movie actors made big money. I was assured that all the artist dreams would be beaten out of my mind.”

Debt be damned, Bergman was besotted. He rented an apartment for Nils, with a little kitchenette and a big bed with red curtains. Unaccustomed to older men being kind to him, Nils wondered if Bergman was his true father. When he asked him this, the writer became tearful. He only wished it were so! Trying to shrug off the emotion, he said if he were Nils’ father, he would pack him off back to school – even if he had to bribe the teachers to put up with him. From now, on Nils would be Bergman’s ‘foster son’, along with a young German lad who was coincidentally also a gorgeous actor who liked to do uppers on trains. Bergman had a type.

Bergman isn’t widely known outside of Sweden, but in 1919 he published a drama based on his relationship with Nils: God’s Orchid. In it, an oafish father watches his beautiful son grow up and wonders how anything so perfect could have been created by him. The boy is compared to Christ, but he’s full of guile, always with his eye on the next opportunity to escape his low upbringing. They bicker and make up and bicker again, with the father’s obsessive love always verging on something more unhealthy.

In Bergman’s letters, he says of Nils, “It’s not his fault he’s a degenerate, nor mine”. But they encouraged each other. Nils doesn’t talk about cocaine in his memoirs, but Bergman joked that if he ever wanted anyone killed, he’d just send them out to party with his foster son.

After drinks, Bergman sometimes liked to arrange Nils where he could sit and stare at him, which isn’t at all skin-crawlingly weird. “You are Jesus to me,” he said on one such occasion. “I will love you as long as I live.” He dared to kiss his cheek. Another time, he gifted his ‘foster son’ with a copy of Death In Venice, which is a bit like handing someone a neon sign blinking “RUN AWAY”.

Aschenbach Off, Hjalmar

But Nils had nothing to run away to. His behaviour seems deliberately coquettish – at one point, he describes undressing in front of Bergman before inviting him to stay over. He always protested their relationship was never more than platonic. “He never tried to rape me,” he wrote, nevertheless describing all the awkward caressing as if that’s just what writers are like. It seems his need for a father figure meant he was willing to put up with almost anything.

Strange men started coming up to the apartment, seeking Nils’ company. That some of these men were publishing professionals makes me suspect Bergman deliberately fed rumours that he was getting more for his money than he really was. Everyone knew what was going on. Or thought they did. The artist Nils von Dardel teased Asther about it. “I know very well Bergman likes you, the pederast.”

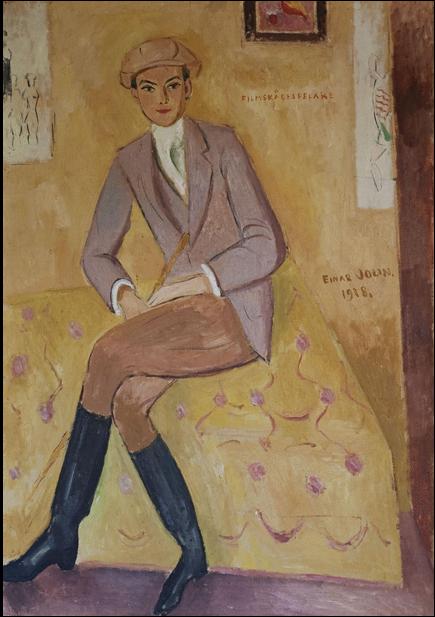

Mauritz Stiller paid close attention. In 1916, he got Nils into the Royal Dramatic Theatre for tuition. “Try not to get expelled,” he said. Next came a film role, in Stiller’s The Wings. It’s a strangely post-modern piece, a film within a film, and you can see what remains of it here.

The Wings was a film about gay desire. At 19, Nils was too young for the lead, but Stiller couldn’t resist writing him a part to keep him close.

“He opened me to the art of loving and enjoying my own sex,” Nils wrote. Again, their relationship was one of power imbalance. Stiller was liable to fly into rages if his demands were not instantly obeyed. “The man had a demonic power over us actors. If he said that we must obtain and drink a teaspoon of piss every day […] I assure you that we would have done it.”

But threats and tantrums were nothing new to Nils. He was getting small film and stage roles, and as soon as he had enough money, he could quit and become the artist he longed to be. Acting was like worshipping a monstrous pagan god, he thought. Fame and decadence were fun, but he was astute enough to see they wouldn’t lead to happiness.

Speaking of unhappiness, Hjalmar Bergman’s wife was less than pleased with her husband’s obsession with this wayward boy. To comfort her, he suggested they have a baby. Isn’t that nice? But Nils had to be the father. Hjalmar only wanted a pretty baby.

Her reaction? “Get some class, deadbeat!” and a slap in the face. Not for Hjalmar. For Nils. Which seems slightly unfair.

Drug use and hectic living eventually killed Bergman. But jealousy put pay to his relationship with Nils, at least in Bergman’s eyes.

A Love Triangle Pyramid Dodecahedron

Augusta Lindberg in 1906

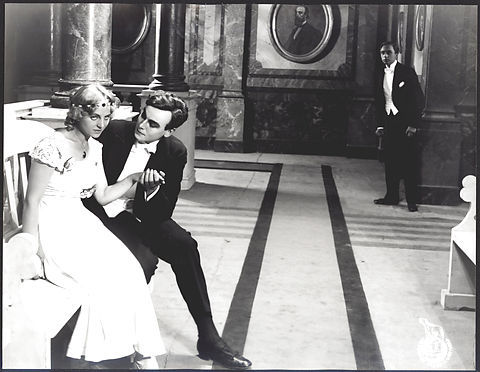

Augusta Lindberg was Bergman’s mother-in-law. She was in her fifties when she first encountered Nils. As a veteran actor and mother of the director Per Lindberg, Bergman and Stiller thought she was a suitable mentor for their new discovery.

Sigh.

He was deposited in front of her with the script for Ibsen’s Ghosts. The play is a typically Norwegian nightmare about syphilis and incest, but Nils flipped through it and remarked Ibsen could have had the decency to throw some actual ghosts in. Like, yawn, am I right?

Augusta was tickled. Surprise-surprise, their weekly private acting classes didn’t involve much acting. Augusta had a taste for exhibitionism. A neighbour complained she had to pour herself a large brandy whenever Nils showed up at the door. At a party, Augusta decided to show Bergman he didn’t own Nils by dragging him into an adjacent room for loud, obnoxious understudying. Nevertheless, Augusta saw the wounded child in Nils and could always sense his anxiety. She mothered him, made sure he ate properly, and helped to keep him in school despite the cocaine and the all-night adventures with Bergman.

Nils saw all this in his unique and adorable fashion: “It has been claimed that there was a tug of war between him and his mother, Augusta Lindberg, and that she emerged victorious. It’s not true. He was merely amused to hear me talk about our games.”

Amused, devastated? One of those.

Stiller also had opinions on Nils’ love life. As well as Augusta Lindberg, there were the actresses Linde Klinckowström and Lutzy Doraine, another fellow student, and a set of twins he could just about tell apart. Over dinner one night, Nils confided in Stiller that he was worried one of the twins might be pregnant. Stiller went ballistic.

“You fucking idiot. Is it not enough that you’re riding that hag Augusta?”

No one would ever buy into a movie star who was saddled with a wife and kids. Was that what he wanted? To be domesticated? If he went ahead with these relationships, Stiller would dump him completely. Worse still, Bergman was withdrawing his affection. It came as no surprise when Nils had a breakdown.

The Real Reason Visiting Hours Are Restricted

“I was an ambitious hunchback not worthy of anyone’s love. No one has ever loved me, and it’s certainly my hideous failure. Why was I such a vindictive and obnoxious person? Was it perhaps my hideous childhood filled with hymns, beating and screams that characterised me?”

Nils retreated to a sanatorium at Saltsjöbaden where he was the youngest by about seventy years. Whether he was off the magic fairy dust at this time was unclear, but he still managed to make another of his trademark disastrous decisions by having a girlfriend over to visit. They conceived a child on the ward.

She miscarried, much to their mutual relief, and they celebrated… by getting pregnant again. They fell out and she went to Switzerland to give birth alone. If he was remotely interested in his child, he doesn’t let on.

If you’re thinking it’s about time his mother gets involved, you’d be right. He arranged to meet with Hilda Asther for the first time since running away. The poor woman looked broken. Anton had set up with another lady and was raising a new family. Nils urged Hilda to divorce him, and promised to support her for the rest of her days. To prove it, he handed her a wad of banknotes. Probably Hjalmar Bergman’s banknotes, but the sentiment was sound. He still couldn’t bring himself to ask her about his adoption. In his mind, she was his foster mother, and she loved him in a distant way that was the best he could hope for. With all his relationships, Nils seemed to have seen himself as someone merely passing through. He never imagined anyone could truly become attached to him.

But where could Hilda go? The Asther house in Malmö wasn’t hers. And Nils surely couldn’t put her up in his sugar daddy’s apartment.

Nils knew just the place.

[Cut to the freshly-divorced Hilda Asther setting up home with Augusta Lindberg.]

Okay…?

Pingback: The Fool’s Way Part III – Bloody Greta Garbo | Somewhere Without Horizons