I have a recurring dream. I’m at my grandparents’ house, the one with the grotty pink shag carpet that enveloped my toes when I was small. I’m alone in the house, wandering through dark rooms with orange floral curtains and vases of papery Honesty, gathering dust. I touch the doorstopper that looks like a slab of chocolate but smells of burned things. The bath towels are scratchy with age.

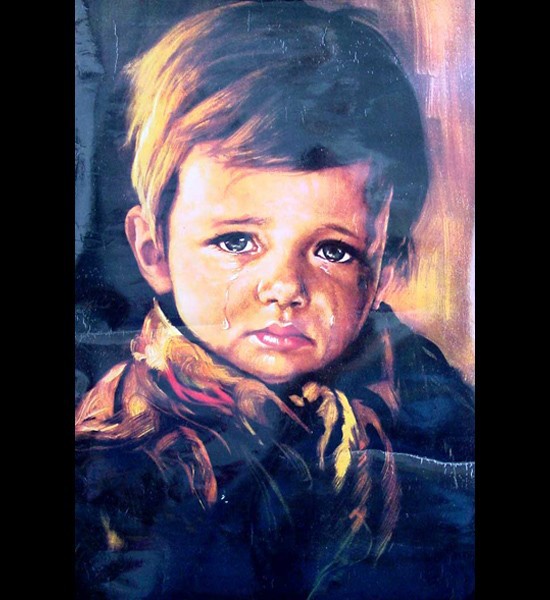

In my dream, I never look up at the Crying Boy.

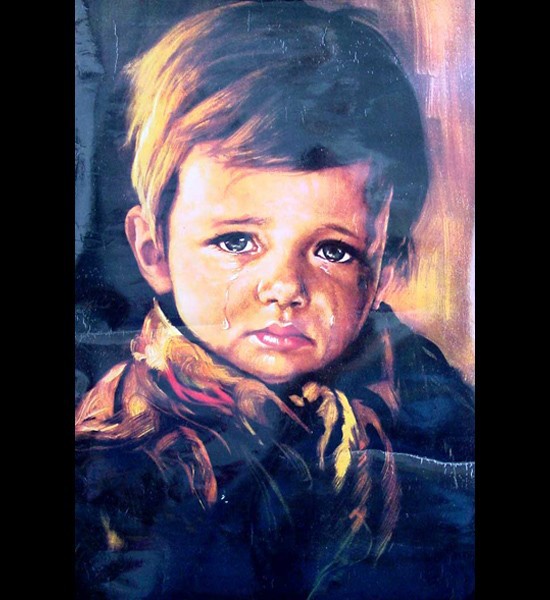

He disappeared from my life long before I was old enough to know his folklore, but even as a kid under ten, I could have told you that painting was cursed. The boy stands in a void, the ruffles of his infant blouse reminiscent of a Tudor prince awaiting the block. Something has made him cry. Not the tantrum of a little boy who’s just flushed his Lego down the toilet – there’s dread. We can’t see who or what he’s looking up at. And what is he pleading for? Comfort? Forgiveness? Mercy?

He disappeared from my life long before I was old enough to know his folklore, but even as a kid under ten, I could have told you that painting was cursed. The boy stands in a void, the ruffles of his infant blouse reminiscent of a Tudor prince awaiting the block. Something has made him cry. Not the tantrum of a little boy who’s just flushed his Lego down the toilet – there’s dread. We can’t see who or what he’s looking up at. And what is he pleading for? Comfort? Forgiveness? Mercy?

You’ll know The Crying Boy. Your own grandparents probably had one. Somehow, during the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, context-free devastated children struck a chord with the British public. There are dozens of versions of the Crying Boy, and by 1985, an estimated 50,000 prints of one Crying Boy variant had been sold in Britain.

It isn’t the first time the British have flocked to purchase pictures of children they aren’t related to. Where nowadays you might have a calendar of Yorkshire Terriers in your kitchen, Victorians exhibited their softer side by collecting sentimental pictures of children. This gauze of innocence still applied if you were a single man, and even if said children were unclothed (looking at you, Lewis Carroll). Sentimental infants go in and out of fashion – look at those unspeakable Anne Geddes bumblebee babies, for instance – but the Crying Boy has an altogether more intriguing history.

In September 1985, Ron and May Hall lost their home in that most retro of household disasters – the chip pan fire – leaving them with nothing but an intact Crying Boy. Days earlier, the couple had laughed at Ron’s fireman brother as he warned them of all the times he had attended blazes where the child had hung weeping on the walls. “Peter told us he wouldn’t have the picture in his house,” May told The Sun, “and nor would his friends at the fire station.” Maybe Peter and his friends just weren’t tacky as all hell. Or maybe they were onto something.

In September 1985, Ron and May Hall lost their home in that most retro of household disasters – the chip pan fire – leaving them with nothing but an intact Crying Boy. Days earlier, the couple had laughed at Ron’s fireman brother as he warned them of all the times he had attended blazes where the child had hung weeping on the walls. “Peter told us he wouldn’t have the picture in his house,” May told The Sun, “and nor would his friends at the fire station.” Maybe Peter and his friends just weren’t tacky as all hell. Or maybe they were onto something.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

For those who don’t know, if it’s printed in The Sun, it might as well be printed on Beelzebub’s toilet paper. ‘Enough is enough, folks’, they wrote, as if the Crying Boy were some kind of foreigner, leftie, or feminist. ‘If you are worried about a crying boy picture hanging in your home, send it to us immediately. We will destroy the painting for you, and that should see the back of any curse there may be.’

Soon enough, The Sun had a pile of Crying Boys, and Sexy Sandra was armed with a can of kerosene to sort them out. The paper’s fine arts correspondent, Paul Hooper, was relieved to report that no muffled cries were heard as the paintings turned to ash.

The South Yorkshire Fire Service were forced to issue a statement assuring the public their Crying Boys would not turn on them, but their chip pans might. The Boy was a running joke in the fire service for years afterwards. Prints became the retirement gift du jour, but the picture retained an aura of bad luck long after the tabloids ran out of fuel. I recently saw the Boy donated to a charity shop, only to be immediately thrown in a skip by the management for being ‘too spooky’.

The South Yorkshire Fire Service were forced to issue a statement assuring the public their Crying Boys would not turn on them, but their chip pans might. The Boy was a running joke in the fire service for years afterwards. Prints became the retirement gift du jour, but the picture retained an aura of bad luck long after the tabloids ran out of fuel. I recently saw the Boy donated to a charity shop, only to be immediately thrown in a skip by the management for being ‘too spooky’.

The legend of Crying Boy lived on. Who was the model? Some say he was an Italian war orphan. Others said he was a runaway who disappeared after posing for his portrait; his anonymity played nicely into the cultural fascination with child murder victims. At school in the 1990s, we had The Boy Ghost who heralded your death if you caught a glimpse of him wandering the corridors. Children are inherently creepy. You can’t have innocence without acknowledging the threat of corruption and death.

The Crying Boy has entered urban legend, where he belongs. Thanks to the Internet, The Sun‘s campaign of burning can continue, despite a BBC documentary in which a leading expert in the field of cursed paintings explains that varnish can have fire retardant properties.

One of the final Crying Boy headlines read: ‘Tears for fears…the portrait that firemen claim is cursed.’ It’s an interesting choice of words. ‘Tears for fears’ relates to psychologist Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream therapy. Janov argued that neurosis is caused by the repressed pain of childhood trauma. This pain could be brought to conscious awareness and resolved through re-experiencing the incident, expressing the resulting pain during therapy. The patient trades their repressed fears for cathartic tears. In short, the inner child screams.

What does therapy have to do with a spooky newspaper hoax? The victims of the boy – or at least the real people who were captivated by the curse – were working class, struggling to make ends meet. Power cuts, unemployment and strikes made the post-war decades grim. Parents and grandparents harboured traumatic memories of recession and war. Perhaps this mass desire to bring innocence and sentimentality into the home was a method of banishing the ghosts of the early twentieth century, putting all those sorrows in a frame and leaving them safely on the living room wall. Maybe that’s why the legend of the Crying Boy still holds the attention – old trauma, like a curse, has a way of bursting out into our cosy homes.

So what happened to my grandparents’ Crying Boy, hanging behind the kitchen door? Their house never burned down. There were no floods. But there was one incident…

Whenever we ate Edam cheese, my mum would roll the red wax between her fingers and tell me the story of a juvenile food fight she had with her siblings in the old house of my dreams. Cheese rind is a natural projectile, and as the five of them pelted each other with Edam wax, a blob of it flew over its target’s head and hit the Crying Boy right on the nose. Choking with laughter, they peeled it off the canvas to discover it had stained the nose clown red. It was permanent, and my nan went spare. Every dinner time became an exercise in not sniggering at the picture, red nosed and tragic forever.

It was around that time that my youngest uncle decided he was going to grow up to be a karate master. He practiced high kicks at the kitchen door beside the Crying Boy, gradually training his muscles until he could connect with the top of the door in one kick. Only one day he got his shoe stuck. Losing his balance, his whole body ended up suspended from his ankle, which broke instantly, leaving him dangling there under the tearful gaze of the red-nosed boy.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

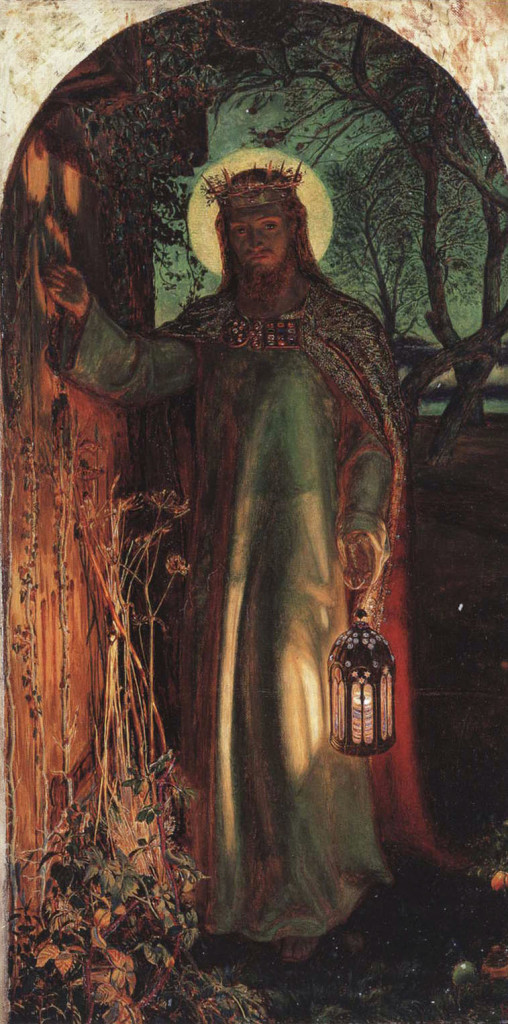

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

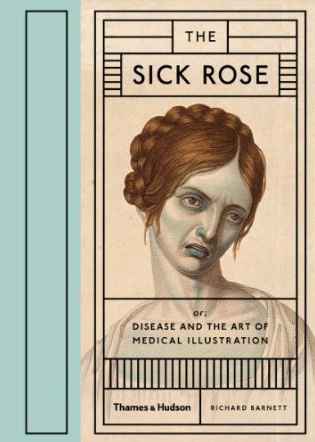

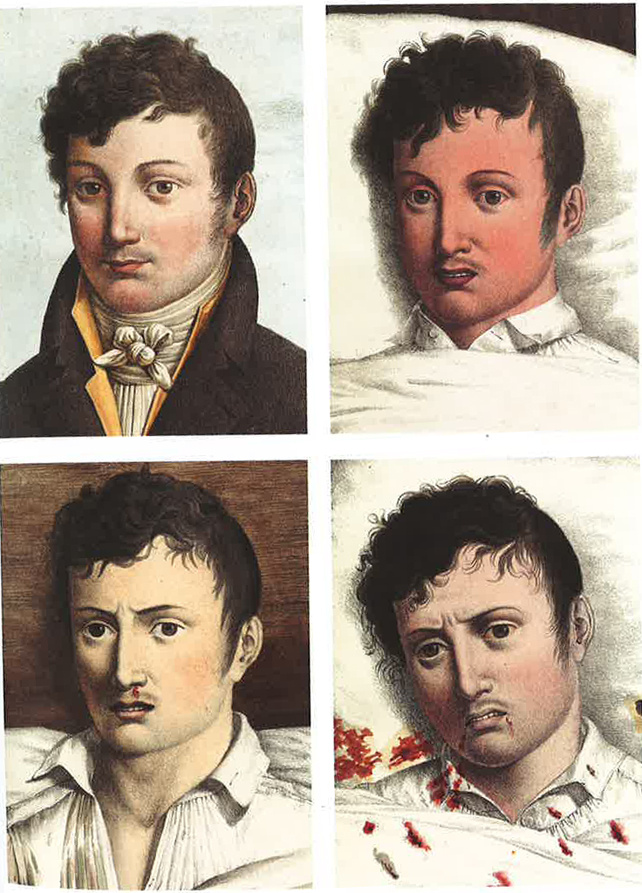

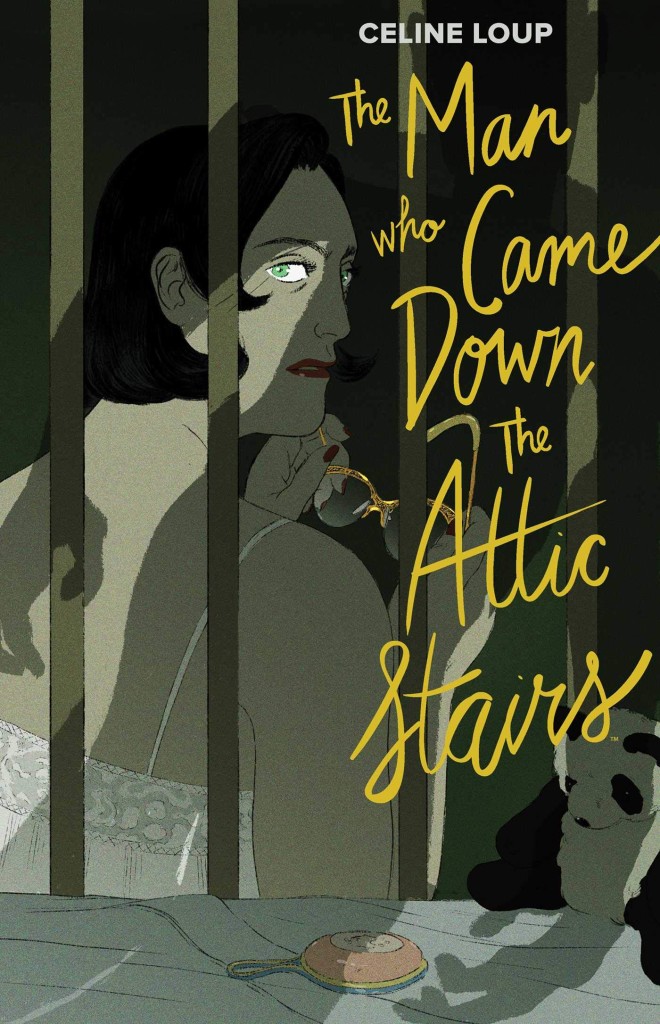

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–