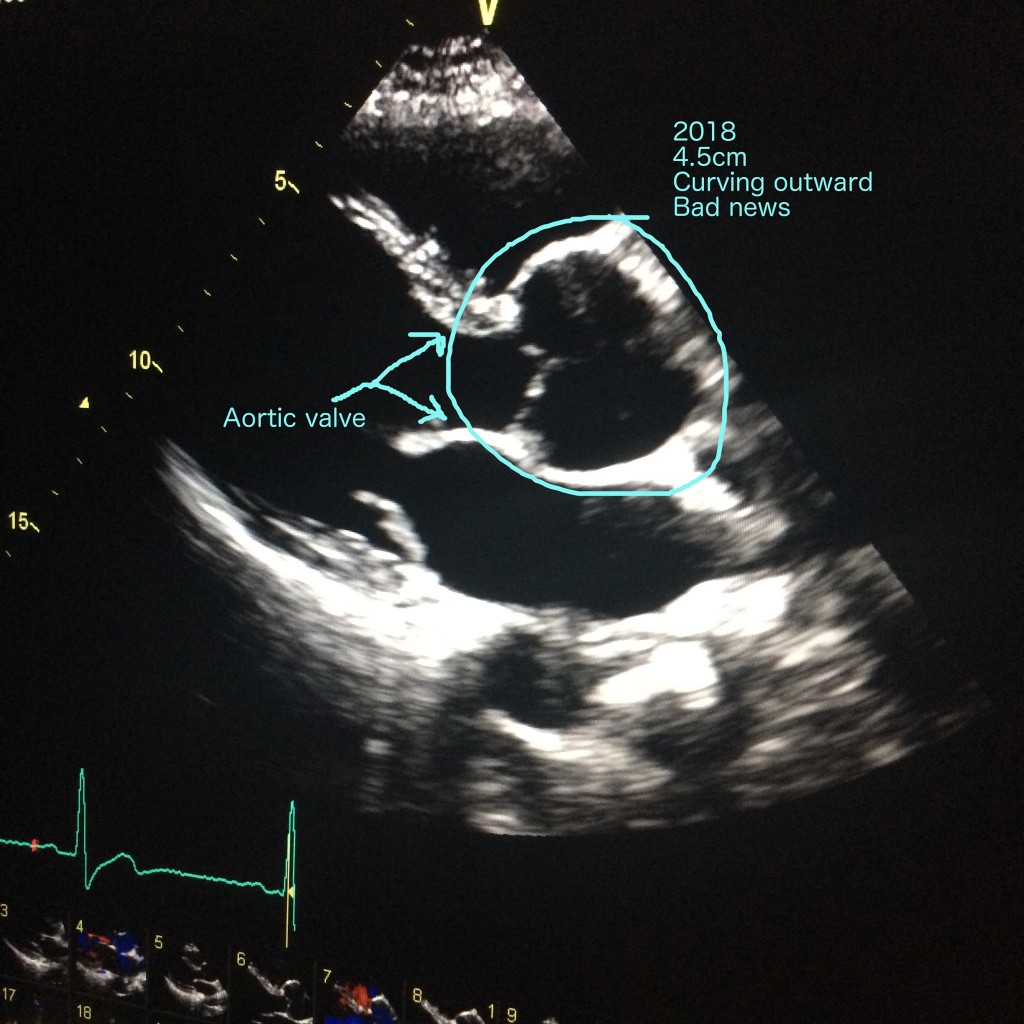

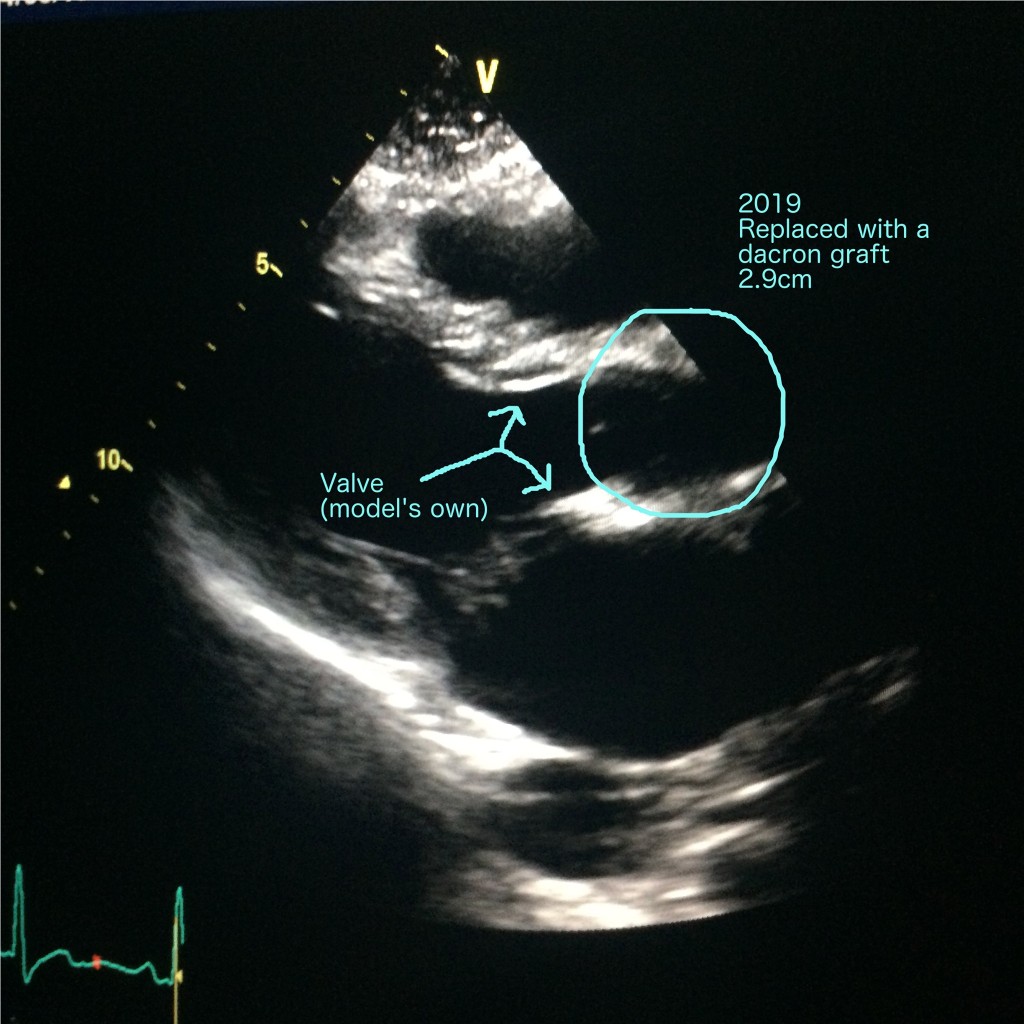

It’s Marfan syndrome awareness month, so it’s about time I finished this series, isn’t it? It’s been a long time since I last blogged about my aortic root replacement and bypass. That’ll be the pandemic. I was in the middle of my final stretch of cardiac rehab when the gyms were first closed, so that effectively put an end to my journey as an outpatient.

I was extraordinarily lucky to have elected to have my surgery in 2019. Any later, and I don’t know how any of it would have worked. I suspect I’d just wait until everything went back to normal, but as I write this – in February 2021 – that day still looks distant.

So. When I left you, I was on the ward, just about able to sit in the chair for an hour a day, in less pain than before, but still impossibly weak. Stage one rehab had begun – a slow walk to the end of the corridor every day, plus one stair if I felt like a challenge.

Something I wasn’t prepared for was losing the dexterity and strength in my hands, albeit temporarily. I couldn’t cope with mugs, so my nurses started giving me coffee in a toddler’s sippy cup. And frankly, being a giant, caffeinated baby was pretty great.

The other thing I wasn’t prepared for was the migraines. Within a few days of my surgery, I started experiencing bright lights in my vision, and eventually those bright lights became crippling headaches, stopping me from completing my all-important task of getting out of bed once a day. This would become the greatest obstacle of my recovery and the year that followed. I’ve done so much reading, visited a neurologist, and had my brain scanned, but still don’t know exactly what caused this. The good news is, I now only suffer one migraine a month. Daily magnesium is the only thing that has helped.

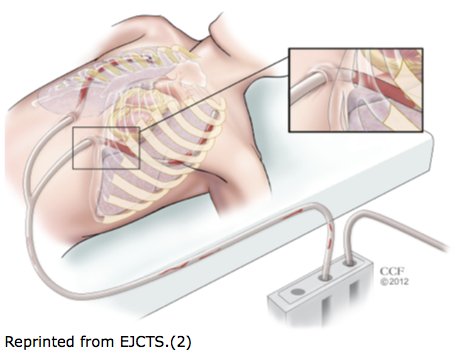

I was in hospital for a total of ten days. Most only stay for four after an operation like mine, but as I’ve said, I kept spiking fevers and they wanted to keep an eye on me. By day nine, my nurses were running out of viable veins to prick me in, and I discovered the extreme delight that is the eight inch cannula. No. Don’t Google it. This isn’t normal, but I have delicate vessels, and after heart surgery, there are only so many places left to try.

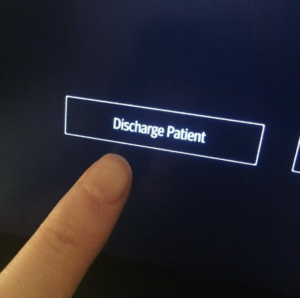

Would you believe, when the time came for me to leave, I was thoroughly institutionalised. The idea of shuffling out into the car park was like boarding a rocket to Mars. Trivial things frightened me – showers, doorsteps, kids running past me. I was a delicate piece of porcelain, a snail without a shell, painfully aware of my broken bones and bruised flesh.

I had to leave my ‘teddy’, my roll of towels, behind. I was scared of that thing in Pavlovian way. The word ‘teddy’ still makes me pause, being so attached to pain, but swapping it for a cushion from home felt strangely reckless. I’d need to carry a cushion for twelve weeks, for sneezing, standing, and rolling out of bed. Make sure yours is soft but firm, with no pointy buttons or zips.

Practical tips: when getting in and out of cars, sit on a blanket with two loose ends either side of you. If you get stuck in a sitting position – which you will – someone can hoist you. Sitting and getting up was my Rubicon, post-op. “She is risen!” I’d say, because every time I successfully stood without aid, it was cause for celebration. Whenever you have to go anywhere – and you’ll be swamped with outpatient appointments – take a thick cushion. Don’t be like me, unable to stand in a GP surgery, while a dozen OAPs look on in amusement. You are forbidden from using your arms to bear your own weight. Indeed, the temptation will be gone altogether. On my first trip out of the house, someone handed me a pint glass of water, and I stared at it in terror. Nothing heavier than a travel kettle full of water – that’s the rule.

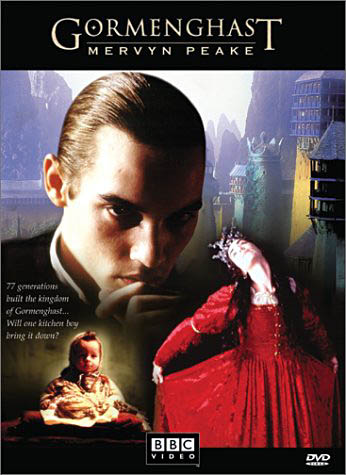

After two weeks, my chest looked like this:

Surprisingly good! Puffy, bruised (note my green hand) but healing steadily.

Then, by six weeks:

For scar minimisation, I used a silicone treatment called ProSil, and it’s seems to have worked. My nurse warned me not to use Bio Oil – no clinical proof of it working, apparently, and if you use it too early it can do more harm than good. Don’t @ me, Big Bio Oil.

In that first month or so, my life was a limited one. Once an hour, I took a sedate walk around the garden. Very sedate. I got to know every blade of grass intimately. I slept all the time. I called them my Cataclysmic Death Naps, because I got a two minute warning and then I was just out. Gone. I’d wake up and think a week had passed. As for food, I was hungry, but only for green things. I craved salads and eggs. How boring. I drank kefir in the mornings, with fresh blueberries. And then there were the bananas. Bananas are good for bone metabolism, and as my bones were healing, I needed one a day. I forced down those yellow bastards. Sometimes it took me three hours. Yes, there were sweeties, too, and wine. You need some joy.

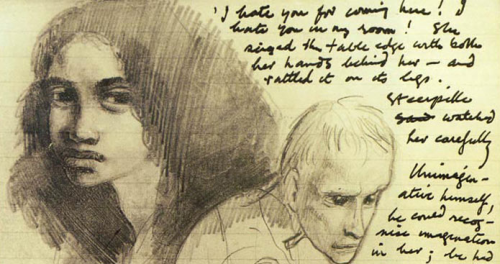

Exhaustion, effort, exhaustion. I learnt to budget my time. A brief shower would cost me an hour of rest, at least. Roll out of bed, no hands, recover. Stand up, recover. Dress without bending over, recover. I had a crate of books begging to be read and I touched maybe two of them in six weeks. Sitting was a trial, so I spent my evenings propped up by pillows in bed, managing one small sketch in a notebook and maybe half a chapter of a novel. All that time to myself, and no energy to enjoy it with!

I noticed my chest scar was becoming hard and bumpy. This is called ‘brawny tissue’ – scaffolding, effectively. It’s temporary, but a little alarming at first. The knot at the top of my sternotomy scar freaked me out the most. After a few weeks, the sharp end was threatening to piece my skin, and I phoned my nurse after a sleepless night, thinking the wires knitting my sternum together were breaking out, Alien-style. No. The knot never broke through, by the way, but it’s quite routine for them to do so, and a nurse will just snip it flat. After about three months, mine just went away. But you’re going to be jumpy about all sorts of small things. One time, the sound of a child bouncing a football was enough to make me say, “I have to go home”.

I was very anaemic. Considering I’d just been through a combine harvester, it wasn’t surprising. The anaemia, combined with a spike of pain in my back, put me back in hospital briefly. I was given iron pills rather than infusions, as my difficult veins weren’t behaving and in the end the nurses decided the stress of repeated attempts outweighed the benefit of instant iron.

So, pain. Enough to keep me awake some nights, but nothing like the pain in hospital. Ridges of muscle popped out from my back, spasms I couldn’t wriggle away from. I’m a side-sleeper, and that wouldn’t be safe to attempt until the twelve week mark. In truth, it took me nine months to sleep that way again. In the meantime, I was given good old diazepam to loosen my muscles and to make me care a little less. This, like all the post-op challenges, would fade away with time. None of this is permanent.

I began stage two rehab after my twelve weeks of sternal precautions were up. Rehab is optional, but if you want to get better, you’ll do it. Classes are 45 minutes long, usually at a local leisure centre, and everyone is a seventy year old man. I’m only mildly exaggerating – I was the only female until my final two classes, and the youngest by at least twenty years, but everyone was shyly friendly – feeling vulnerable, like me – and had a story to tell. Tough old boys who’d keeled over on golf courses, younger guys who’d lived a bit too hard. The exercises are simple, gentle, and last a minute each. A minute of gentle weight-lifting, a minute of walking, a minute with a resistance band, and so on. This will all seem daunting at first, but the nurses are constantly checking your pulse and oxygen. I usually spent the rest of the day in a Cataclysmic Death Nap, but rehab was a good experience for me. It gave me an excuse to buy this t-shirt, for instance:

I graduated rehab in the summer, seven months post-op. Got a little certificate and everything. Since April, I’d lost most of my muscles, my stamina was rock bottom, and my body felt like someone else’s. I was down about it sometimes, but that unhappiness was intermingled with awe at what I’d survived and each new milestone I was meeting. Some of these moments were hilarious. I once stood up faster than a ninety-year-old lady in a neighbouring chair and did an inward fist-pump. I learnt to pick socks off the floor with my feet and toss them into the air to catch. BBC’s sitcom Ghosts was the highlight of my week, but it hurt too much to laugh, so I’d try to hold it in, which only made it funnier. Being able to enjoy the absurdity is a real asset after something so massive.

Stage three rehab is voluntary, but I signed up anyway. It’s largely the same as stage two, only you do it alone, in a real gym, with a pulsometer and oxygen monitor on stand-by. I walked twenty minutes to get to the gym, worked out gently but determinedly for forty-five minutes, then walked home. Every Tuesday, I felt like Geralt of Rivia. Sometimes I didn’t even need a nap afterwards.

And then… 2020 happened. The gyms closed, I stayed at home, and any plans for a one-year anniversary party were shelved. But recovery didn’t stop. At twenty months, I found I could sleep on my left side again, hearing my heart loud and strong. My sternotomy scar is pale and flat. My ankle scar is invisible, and my bypass incision on my thigh is white and soft. Of my lung drains and pacemaker, three Xs remain, and at the base of my neck are two perfect white dots where the catheter entered. I love them all.

I want to thank everyone who got me through open heart surgery. Mister Nashef my surgeon, my whole surgical team (who I met but mostly can’t remember because drugs), all my hardworking nurses and therapists, the cheerful cleaners who chatted to me even when I was wittering rubbish, my rehab team and fellow zipper club members, my family, my friends, my partner, my gentle dog, and all the Internet heart veterans who held my hand virtually through the whole thing.

And now… back to life.