This post is brought to you by a cocktail of painkillers, hypnotics, and anxiolytics, administered by a lovely NHS anaesthetist whose name I can’t remember – only the sight of her leaning over me with a smile: “You’re going to forget my name.”

Just some routine Marfans stuff. But two days later, I’m still swimming through dreams. I like to think the lingering hypnotics are giving me the authentic Rossetti experience, minus the raccoon hiding in the wardrobe. And the genius.

Hanging onto the tail of this wooziness, I want to talk about childhood, but also about Jan Švankmajer’s gorgeously surreal 1988 film, Alice: “A film for children… perhaps.”

Years ago, a counsellor complimented my socks. They were pale blue and white striped, up to the knee, and they were perfect, she said, “because you’re Alice in Wonderland.”

This probably wasn’t wise of her.

Like a lot of only children travelling with military parents, I was prone to dissociation. That’s the psychology term for intense daydreaming. And I mean intense – to the point that reality was almost entirely blocked out for the majority of every waking day. Mostly, it was paradise, but there were snags. Teachers found they had to full-on yell to catch my attention. I once kicked a cannonball-sized hole through a porter cabin wall without noticing.

Dissociation is a creative coping mechanism for when life is unstable or lonely. It’s very much like the intravenous sedative experience – a protective measure that picks you up and whisks you away. Eventually, children who habitually dissociate grow up to remember more about their dream worlds than the reality of the past. Some of them become writers. Ahem.

Onto Alice. As a chronically fantastical child, I was rankled by the Disney version of Alice In Wonderland. It was all so very pastel, so very clean. Nothing pristine, I knew, could ever be magical. Childhood is frightening, and nonsensical, and inappropriately hilarious – much like the original Wonderland tales.

Children inhabit another planet. Lewis Carol knew that.

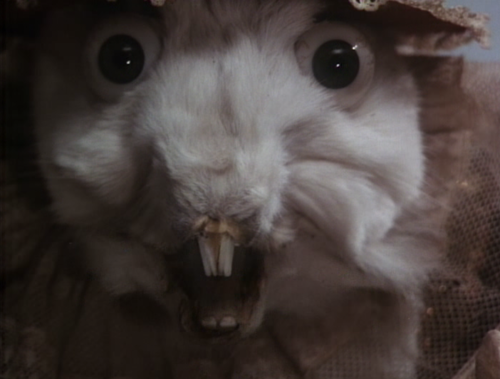

So on the other hand, you have Jan Švankmajer’s Alice. A film for children… but probably not for parents. The White Rabbit is taxidermy, leaking sawdust. Socks have teeth and the jam is full of drawing pins. Wonderland itself is a wreck of broken china and splinters, pickled specimens, potted tongue (prone to slithering), and other Victorian relics. Alice – the only living person in the film – has a way of turning into a decidedly spooky china doll and back again, tearing off the chrysalis of painted skin and making a run for it. Like the doll, her facial expression never changes. She never smiles or frowns. Those are things you do for others, and this Alice is content to be alone with her imagination.

Drowsy and doped as I am, it strikes me how strangely authentic Švankmajer’s vision of childhood imagination was.

In 1989, the year after Švankmajer released Alice, I was three. The Navy posted Dad to Scotland, and we ended up living on a dismal estate near a submarine base. Someone had spray-painted a peace symbol on the garden fence for our arrival. I wasn’t ready for school, and we never stayed anywhere long enough to make friends. I think I tried, on a few sparse occasions, but it was so much effort for so little return when inside was infinitely better than outside.

Perhaps it was the jerky stop-motion animation, or the twisted quality – lurking on the indistinct border between dreams and nightmares – but watching Švankmajer’s Alice for the first time a few weeks ago, I began to spontaneously remember scraps of day-to-day surrealism from that time in Scotland.

Someone – I forget who – told me bubbles were living things, and that when you popped them, they died.

There was a nearby play park where a boy knocked himself out trying to make the swings turn full circle. I saw his body in a red tracksuit, face down on the ground. ‘Cracked his head open’, I thought for years, was literal. Bash the hinge hard enough and the skull pops open like a spring-loaded box.

That play park was an island of concrete amongst hillocks of unkempt greenery. One day, some other children took my doll, so I wandered off to where you could see the Forth Rail Bridge, muddy-bloody coloured, in the distance. Over a hill, I found the skull of a ram, picked clean. The coiled horns looked like the fossils in my dinosaur books. I can’t recall the doll.

From the spare bedroom, if the light was good (by Scottish standards), you could see dark cylinders moving slowly through the cold seawater. I’ve never grown out of the fear of submarines, but the house held hidden dangers of its own. I was playing in the garden. Making a pile of gravel. The house had been arsoned before we moved in, so the gutters full of gravel also contained all the glass from the shattered windows. Not that I noticed. I was grabbing handfuls, piling it up, until I registered I was bleeding from dozens of tiny cuts. I took myself up to my parents’ bedroom and triumphantly held out my hands to them. It didn’t hurt.

A fisherman on a jetty shouted at me for dropping a stone in the sea and disturbing the fish.

“I want to cut him in half,” I said, and I can still clearly see the satisfying image in my mind, of a man sliced in two like a pink salmon.

Sugar, spice, and murder fantasies. There’s a whimsical grotesquery to childhood I think we’re programmed to erase. Perhaps it’s only free to come out when we’ve been dosed up by friendly anaesthetists without names.