I’m back on Patreon talking about one of my favourite books, in all its deranged glory. Join up for £1 to watch.

I’m back on Patreon talking about one of my favourite books, in all its deranged glory. Join up for £1 to watch.

It’s happened. I’ve pivoted to video. Over on Patreon, I’m talking about As Meat Loves Salt, one of my all-time favourite novels about stabbing people and establishing a cult during a brutal civil war. It’s £1 to join, and you get a bookmark in the post.

I’m fairly new to comics and graphic novels. Since my surgery I’ve been reading almost as many comics as novels. Being forced to slow down has had its advantages – I’ve been getting through some brilliant graphic works. The latest is Celine Loup’s The Man Who Came Down The Attic Stairs.

Celine Loup is an award-winning cartoonist seen in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Penguin, and many more prestigious publications. Her work has been honored by The Ignatz Awards, Best American Comics, American Illustration, The Society of Illustrators, and CMYK. She is currently working on Hestia, a serialised erotic Gothic comic set in Ancient Greece.

The Man Who Came Down The Attic Stairs is as Gothic as they come. A loving couple expecting their first child move into a beautiful country house. When Emma’s husband goes to open the locked attic room, she hears a commotion and rushes to investigate. She finds her husband unscathed, but somehow… different.

It’s a Gothic interpretation of the anxiety surrounding motherhood written at a time in Loup’s life when she was ambivalent about starting a family herself and wanted to explore those difficult feelings in a safe place. That’s good horror, really, isn’t it? A sandbox for our worries.

I really enjoy Loup’s art style. It’s painterly, and bodies appear soft and natural. Wide sweeping vistas zoom in to uncomfortable close ‘shots’, raising the tension of isolation and paranoia. I love how Loup conveys loneliness through groups of almost empty panels lingering on repetitive household noises, on tasks that will never be complete. Always present is the baby’s scream, in wavering bold text – is she an exhausting burden, or is she trying to warn Emma of something?

There’s a lovely consciousness throughout of the absurdity of Gothic, that Castle Of Otranto camp that lovers of the genre embrace. The giant portrait of Freud behind the therapist’s head is very funny, but also perfectly illustrates the weight of outdated psychology hanging over women with postpartum depression and psychosis. There’s one particular moment of the uncanny that stands out – simple, elegant and absolutely chilling – but I won’t give anything away here.

Overall, this is a slice of well-executed psychological horror I’ll be returning to. Other reviews have made comparisons to Shirley Jackson, and they are spot on.

A belated happy Halloween to you all!

Ghost stories of the nineteenth century are enjoying a new lease of (un)life at the moment, with publishers scouring the archives for stories that have never since been republished or anthologised. Anyone who loves the genre knows the titles that regularly enjoy fresh publication, and, classic and beloved as they are, it can feel like they take up unnecessary space. There’s a rich untapped seam of ghostly tales, especially by women, and Black Shuck Books are working to rescue these stories from obscurity.

I actually received A Suggestion of Ghosts last Christmas and haven’t had a chance to get into it until now, but it’s spooky season and I felt the need to expand my knowledge of hitherto unknown authors.

First of all, what a fun cover. You know you’re in for a luxurious ride of delicious cliches. The collection is full of ancestral homes, hidden passageways, indomitable heroines with an eye for eligible bachelors, and a whole crew of spectres from the beyond. All the good stuff.

Of course, a good ghost story isn’t merely about a ghost, and there’s a range of interpretations of the form in A Suggestion of Ghosts. The collection shows what women authors of the latter half of the nineteenth century were doing with the ghost trope; fully indulging in the high Gothic or being more playful, working across genres.

The editor, J.A. Mains has typed out the stories by hand rather than relying on scanning software, so original spelling is preserved, which I appreciate. I love the biographical information on the neglected authors, too, some of whom published anonymously or only once. Others were prolific, like Katharine Tynan who published over a hundred novels and was championed by WB Yeats. There’s a real mix here. Tynan, with her knowledge of Irish witch lore, managed to elicit an “Oh, gross!” from me, which isn’t easy.

There are a couple of switcheroo type stories where the ghostly element is a device for a more straightforward romance. These were popular in ladies’ magazines, being less risqué than Gothic tales or sensation stories. In fact, they were generally aping them. The Ghost of the Nineteenth Century by Phoebe Pember is one of these, and I didn’t take to it, mainly because it’s full of nasty racist asides. The author was a Confederate nurse during the American Civil War. At the Witching Hour by Elizabeth Gibert Cunningham-Terry is a much better example of an author playing with genre and cutting edge technology in the same vein as Bram Stoker.

There are, predictably, more stories about or by the aristocracy than otherwise. That’s partly a genre thing (a sprawling ancestral home as your setting is basically the law) and partly a class thing (how many working class women of the late nineteenth century had the time, energy or encouragement to write?), but Lady Gwendolen Gascoyne-Cecil’s The Closed Cabinet is actually one of my favourites of the bunch. A young woman staying at her childhood friends’ home encounters rumours of a family curse, and though she laughs to be given ‘the haunted room’, the resulting nightmares lead her to make a terrible choice which might just change history.

But by far my favourite is A Speakin’ Ghost by Annie Trumbull Slosson. No stately homes here, and no dazzling heroines with a queue of suitors. Written entirely in patois, I thought it was going to be a slog to read, but the story unfolds into sensitive study on what ghosts mean to lonely people, to the unwanted, and how a ghostly encounter can mean radically different things to different people. This is why I love ghost stories. I want to see what they can do.

Overall, A Suggestion of Ghosts is an enjoyable collection showcasing a range of authors’ responses to supernatural encounters, ghost hysteria, and Gothic romance. There are authors who enjoyed success in their lifetimes, and those who only ever got one shot. This makes it an interesting and important snapshot of the period, and some of these tales will stay with me for a good while. Honestly, the more of these anthologies the better, and I’m happy to report Black Shuck Books have already published a sequel, which I’ll definitely seek out.

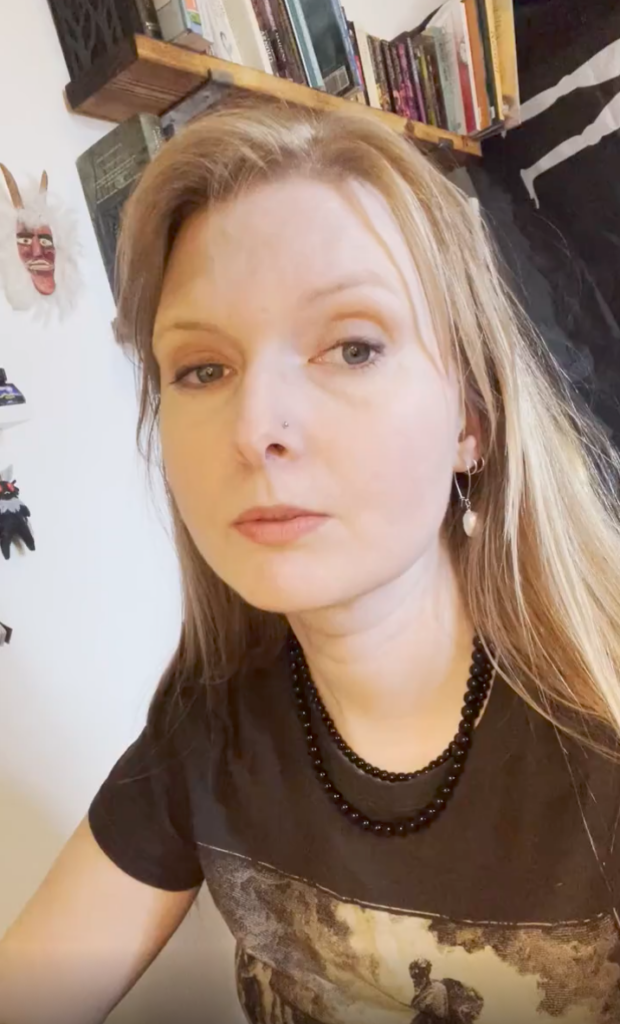

I’m still translating Nils Asther’s memoirs of silent stardom from Swedish. Catch up on parts I and II. And look – Nicole of Strange Fiction is providing illustrations!

Meanwhile, in the Roaring Twenties…

Meanwhile, in the Roaring Twenties…

When he wasn’t yelling at him and making threats, Mauritz Stiller liked to tell Nils he was his favourite. He probably told Greta Garbo that too.

Stiller helped the teenage Greta Gustafsson come up with a new name and a new look. He had her lose weight and fix her teeth, chose shoes to make her feet look smaller (Stiller had a complex about the size of his own feet, so hey, why not everyone else’s?) and began to cultivate the special something that would make her a star. Rumour had it, her beat her. There was plenty of whispering about Greta Gustafsson. The girls at the Royal Dramatic Theatre called her untalented and ugly, but Stiller believed in Greta with his characteristic possessive fervour, and she adored him.

There was plenty of whispering about Nils, too. He was getting decent reviews for his stage work, plus plenty of film roles, but his fellow students were sure he was only tolerated because he was sleeping with the great Augusta Lindberg. Augusta’s exhibitionism wasn’t doing much to dispel the gossip. On one occasion, he was forced to climb out of a window mid-session to preserve her honour. She was perfectly happy with her quota of honour, but it was nice of him to make the effort.

When Nils met Greta, they were both students. Their first encounter would haunt him for the rest of his life. She wasn’t anything special to look at, not at first, but then…

“Suddenly she looked up and into my eyes. It felt like I was hit by a thunderbolt. I stared bewitched at her. But it seemed like she did not notice me. Her girlish face seemed to me wonderfully beautiful. My whole body was carried by a pleasant springing sensation, which I never before experienced, and the effects of which I could never completely free myself from. Something strange had happened inside me. The peculiar theatre student had lit a fire of love in me, bordering on bliss. It insisted that I must join with her forever.”

Within three days of setting eyes on her, Nils proposed for the first time.

This was typical Nils. Where Greta Garbo was supposed to fit alongside Augusta, Hjalmar, Stiller, Lutzy, the twins, and the estranged mother of his child, I don’t know. She wasn’t sure either. With grace, she told him she was married to her craft.

Anyway, there was Linde Klinckowström to consider. Linde was a Swedish countess who would become known for daring solo trips across Europe on horseback. She was intelligent and artistic, and Nils being Nils, he couldn’t help but flirt with her. They met when she was appearing as an extra in a film, dressed in men’s breeches. He said he had a way of falling in love with girls in trousers. Well then, she said, she said she ought to wear them more often. Somehow, “Ooh, I might have to propose”, came out of someone’s mouth, maybe even hers. At last, said his friends, a nice, relatively normal girl to keep him on the straight and narrow. Straight and narrow were new concepts to Nils, and he wasn’t sure what to do with them. Linde presented him to her parents, half-joking about a romance. She was nobility, after all, and though he looked the part, he had a commoner’s accent. But Linde’s brother was an artist, a good one, and he counselled Nils to leave the acting world and follow his dreams of painting. He and Linde were astute enough to see Nils’ self-destructive nature. Film would only encourage it, as would mad love affairs.

It was sound advice, so naturally he didn’t take it. Linde and her aura of calm would appear to him in dreams for years to come, begging him to slow down. Gently, she broke off their brief, strange relationship, leaving him free to pursue… more brief, strange relationships.

Oh My God, Stop Falling In Love

The Linde hangover was over. Now Greta Garbo was his one true love.

Where did this alluring creature hang out? Where could he loiter in the hope of bumping into her? There was her house, of course, but any idiot can lurk outside someone’s home address (and he did). You’ve got to think creatively. You have to go somewhere you’ll have something to talk about, things to do.

Her father’s grave, for instance.

And so he hung around in the snow amongst the headstones. Looking forlorn had always worked on Hjalmar, but it wasn’t going to cut it with Greta. What was this ‘just friends’ concept she was talking about? Nils thought he was losing his mind. Perhaps Mauritz Stiller had threatened her too?

He and Greta actually had a lot in common. They had the same sense of humour and ability to see through bullshit. And Greta had a similarly horrible childhood to Nils, only far poorer:

“It was eternally grey—those long winter’s nights. My father would be sitting in a corner, scribbling figures on a newspaper. On the other side of the room my mother is repairing ragged old clothes, sighing. We children would be talking in very low voices, or just sitting silently. We were filled with anxiety, as if there were danger in the air.”

This was something they could bond over. Post-divorce, Anton Asther had settled down with his new wife and was producing more children. According to rumour, he hadn’t told his new family that his old one even existed. But Nils was becoming well-known in Sweden, and the Asther name was uncommon enough that surely someone would start asking questions. Nils decided to contact Anton one last time. For what, who knows? Maybe acceptance. But Anton refused to meet. Nils had brought the shame of ‘sawdust’ onto their name, he said. He was nothing but a simple clown.

But like Greta Garbo, the clown was going places. Friedrich Zelnick, one of the most important director-producers of the day, called Nils his ‘darling’. Bidding wars started up between directors determined to have him. Nils pretended not to care. He liked to see how far he could push it. “It’s all just so boring,” he shrugged, which only made the directors hurl more cash at him. Greta was in Turkey, making movies with Stiller. Nils was filming in Berlin, Vienna, and Sicily – doing what? He couldn’t remember.

“I have a peculiar talent for forgetting the names of all the bad films I’ve been in. Guess I’m just lazy.”

This may have been more down to his lifestyle than the quality of the films. Depressed by the chaos of his personal life, pining for Greta, he threw himself into further hedonism. Deciding that Lutzy Doraine was now the one and only woman for him, he went AWOL from the theatre to go on a mad dash across Europe to see her while she went travelling. The pursuit of his beloved consisted of a few months of daylight drinking in public spaces, romantic encounters with people who didn’t speak any of the languages he knew – none were as bewitching as Lutzy, of course, even the lady with the lovely ankles – and further day drinking. If he could just get all the way to Egypt, maybe he could become like a romantic knight, riding a camel to the pyramids. But Egypt turned out to be full of honking cars and strewn with rubbish. And it wasn’t really Lutzy he was after. He only ever seemed to want to run away.

In Nils’ own estimation, he was “totally deranged” at this point. Hjalmar Bergman, besotted as ever, lamented the behaviour of his “little idiot”. Keeping up with Nils was killing him. When Hjalmar wasn’t face-down in a mountain of cocaine, he was taking his feelings for his foster son to the brothels. Nils had begun to talk about America. It was the logical next step for his career, and Greta Garbo was already there, making a mark. Hjalmar couldn’t bear to lose the handsome youth he had idolised for so long.

After a night of heavy drinking, the writer broke down on Nils’ shoulder. Why had nature cursed him with such a repulsive face? Nils did his best to console the older man. Hjalmar had no need of something so trivial as good looks. He had been blessed by the Muses, and Nils admired and loved him for it. But he was missing the point. Bless him, he was quite good at missing the point. In four more years, Hjalmar would die alone in a Berlin hotel, wrecked by alcohol.

Mephistopheles Doesn’t Care About Your Hangover

On the 17th of January 1927, Nils spent his 30th birthday alone. He composed himself this message:

“Congratulations on the birthday, you old rascal! Not that you deserve it, but may your future become light and fun, with great success. Well, why not world renown to satisfy your vanity? Beautiful girls, a thousand of them, and coins in large quantities, and good health so that you can enjoy these creature comforts. May all your dreams come true, even the idiotic ones. And when you’re drinking in a villa in Italy or Spain, where you can live in peace and with peace of mind, free from ambitions and desires, may you finally get your easel, canvases, brushes and paints. Cheers to you, old boy.”

Despite drowning his loneliness in champagne, it was a pretty good birthday. Paramount had noticed this Scandinavian heartthrob and were sending a representative over to Sweden to talk to him right away. But they were beaten to his door by rival company United Artists. Literally. They just barged in.

“I had not yet got out of bed and was waiting for morning coffee, when there came a knock on the door. Unannounced, it was a Mr. Berman from the U.S.A. Hat in hand, an extinct cigar hung from the corner of the mouth. ‘Hallo, Asther! You are going to Hollywood. You have a future there. You’re the type that the girls will run after.’ Uninvited, he had thrown himself down in an uncomfortable chair. He mistook my silence for awe, for he galloped in with a bunch of promises of life in Hollywood. He represented the prominent United Artists and told me what I already knew, that it was owned by Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Norma Talmadge with Joseph Schenk as the Director. I would stay at the finest clubs and a Cadillac would be the only car for me, etc. Where the hell was the coffee…?”

Very politely, for someone hungover in his pyjamas, Nils explained he was flattered but had an appointment to keep with Paramount. To Hell with Paramount, said Berman. United Artists would beat any offer from those shmucks. Also, how do you feel about pretending to be twenty-five?

By the end of the month, Nils would be in America, having the time of his life.

“There is nothing that I more bitterly regret than leaving Sweden and giving myself to the violence of film,” he wrote, years later. “Above all, I let myself be caught by the untruthful Hollywood dream factory, where I experienced my life’s most terrible nightmares.”

It’s going to be so much fun, guys.

TBC.

I’ve been translating Nils Asther’s memoir from Swedish because I apparently have nothing better to do. Catch part one here.

It’s fair to wonder what would have happened to Nils Asther had he not attracted the attention of Mauritz Stiller that evening. The teen had no money, no qualifications, no home to go to, and in his mind at least, no family.

Stiller was born in Helsinki in 1883, and fled to Sweden to avoid being drafted into Czar Nicholas II’s army. He was a pioneer of silent films, writing and directing more than thirty-five features in his lifetime. The night he laid eyes on Nils, Stiller was eating out with a fellow screenwriter, Sam Ask. Stiller ushered Nils and his companion over to Ask. “Doesn’t this one look like an actor?”

(Nils’ friend was ignored for the rest of the evening. Poor boy, he was lovely, but he had a face like the back of a tram.)

Soon they were joined by a hefty gentleman with thick curly hair. He looked out of place in the noisy eatery, standoffish and over-eager at the same time. This was Hjalmar Bergman, a respected author. Having established himself as highly literary and intellectual, the death of his father brought about huge debt, and Bergman was forced to write more crowd-pleasing works. This required research, such as drinking, snorting cocaine, and fraternising with gorgeous young men.

Tonight was Bergman’s lucky night.

“He looked at me as if I were an angel fallen from the skies,” Nils wrote. “It took a while before he sobered up. He asked me my name and what I did. I told him that I was kicked out of my adoptive parents’ house and from the Spyken school in Lund. Now I had decided to become an artist. Hjalmar Bergman reacted negatively. Not many artists could live on their jobs. Such fancies! Movie actors made big money. I was assured that all the artist dreams would be beaten out of my mind.”

Debt be damned, Bergman was besotted. He rented an apartment for Nils, with a little kitchenette and a big bed with red curtains. Unaccustomed to older men being kind to him, Nils wondered if Bergman was his true father. When he asked him this, the writer became tearful. He only wished it were so! Trying to shrug off the emotion, he said if he were Nils’ father, he would pack him off back to school – even if he had to bribe the teachers to put up with him. From now, on Nils would be Bergman’s ‘foster son’, along with a young German lad who was coincidentally also a gorgeous actor who liked to do uppers on trains. Bergman had a type.

Bergman isn’t widely known outside of Sweden, but in 1919 he published a drama based on his relationship with Nils: God’s Orchid. In it, an oafish father watches his beautiful son grow up and wonders how anything so perfect could have been created by him. The boy is compared to Christ, but he’s full of guile, always with his eye on the next opportunity to escape his low upbringing. They bicker and make up and bicker again, with the father’s obsessive love always verging on something more unhealthy.

In Bergman’s letters, he says of Nils, “It’s not his fault he’s a degenerate, nor mine”. But they encouraged each other. Nils doesn’t talk about cocaine in his memoirs, but Bergman joked that if he ever wanted anyone killed, he’d just send them out to party with his foster son.

After drinks, Bergman sometimes liked to arrange Nils where he could sit and stare at him, which isn’t at all skin-crawlingly weird. “You are Jesus to me,” he said on one such occasion. “I will love you as long as I live.” He dared to kiss his cheek. Another time, he gifted his ‘foster son’ with a copy of Death In Venice, which is a bit like handing someone a neon sign blinking “RUN AWAY”.

Aschenbach Off, Hjalmar

But Nils had nothing to run away to. His behaviour seems deliberately coquettish – at one point, he describes undressing in front of Bergman before inviting him to stay over. He always protested their relationship was never more than platonic. “He never tried to rape me,” he wrote, nevertheless describing all the awkward caressing as if that’s just what writers are like. It seems his need for a father figure meant he was willing to put up with almost anything.

Strange men started coming up to the apartment, seeking Nils’ company. That some of these men were publishing professionals makes me suspect Bergman deliberately fed rumours that he was getting more for his money than he really was. Everyone knew what was going on. Or thought they did. The artist Nils von Dardel teased Asther about it. “I know very well Bergman likes you, the pederast.”

Mauritz Stiller paid close attention. In 1916, he got Nils into the Royal Dramatic Theatre for tuition. “Try not to get expelled,” he said. Next came a film role, in Stiller’s The Wings. It’s a strangely post-modern piece, a film within a film, and you can see what remains of it here.

The Wings was a film about gay desire. At 19, Nils was too young for the lead, but Stiller couldn’t resist writing him a part to keep him close.

“He opened me to the art of loving and enjoying my own sex,” Nils wrote. Again, their relationship was one of power imbalance. Stiller was liable to fly into rages if his demands were not instantly obeyed. “The man had a demonic power over us actors. If he said that we must obtain and drink a teaspoon of piss every day […] I assure you that we would have done it.”

But threats and tantrums were nothing new to Nils. He was getting small film and stage roles, and as soon as he had enough money, he could quit and become the artist he longed to be. Acting was like worshipping a monstrous pagan god, he thought. Fame and decadence were fun, but he was astute enough to see they wouldn’t lead to happiness.

Speaking of unhappiness, Hjalmar Bergman’s wife was less than pleased with her husband’s obsession with this wayward boy. To comfort her, he suggested they have a baby. Isn’t that nice? But Nils had to be the father. Hjalmar only wanted a pretty baby.

Her reaction? “Get some class, deadbeat!” and a slap in the face. Not for Hjalmar. For Nils. Which seems slightly unfair.

Drug use and hectic living eventually killed Bergman. But jealousy put pay to his relationship with Nils, at least in Bergman’s eyes.

A Love Triangle Pyramid Dodecahedron

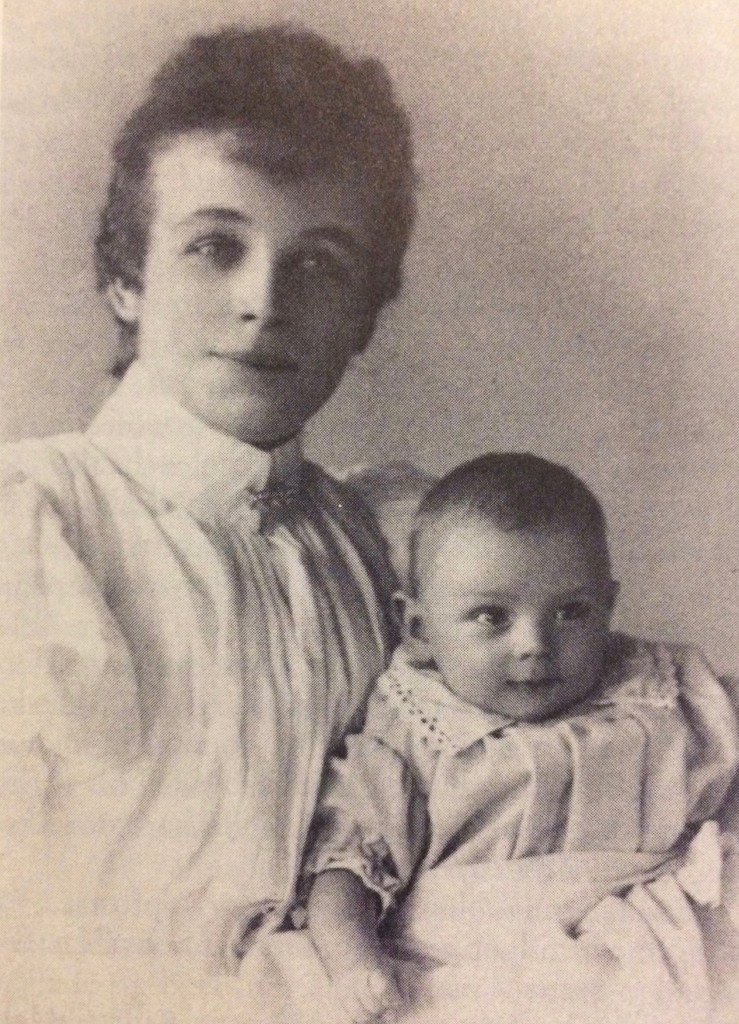

Augusta Lindberg in 1906

Augusta Lindberg was Bergman’s mother-in-law. She was in her fifties when she first encountered Nils. As a veteran actor and mother of the director Per Lindberg, Bergman and Stiller thought she was a suitable mentor for their new discovery.

Sigh.

He was deposited in front of her with the script for Ibsen’s Ghosts. The play is a typically Norwegian nightmare about syphilis and incest, but Nils flipped through it and remarked Ibsen could have had the decency to throw some actual ghosts in. Like, yawn, am I right?

Augusta was tickled. Surprise-surprise, their weekly private acting classes didn’t involve much acting. Augusta had a taste for exhibitionism. A neighbour complained she had to pour herself a large brandy whenever Nils showed up at the door. At a party, Augusta decided to show Bergman he didn’t own Nils by dragging him into an adjacent room for loud, obnoxious understudying. Nevertheless, Augusta saw the wounded child in Nils and could always sense his anxiety. She mothered him, made sure he ate properly, and helped to keep him in school despite the cocaine and the all-night adventures with Bergman.

Nils saw all this in his unique and adorable fashion: “It has been claimed that there was a tug of war between him and his mother, Augusta Lindberg, and that she emerged victorious. It’s not true. He was merely amused to hear me talk about our games.”

Amused, devastated? One of those.

Stiller also had opinions on Nils’ love life. As well as Augusta Lindberg, there were the actresses Linde Klinckowström and Lutzy Doraine, another fellow student, and a set of twins he could just about tell apart. Over dinner one night, Nils confided in Stiller that he was worried one of the twins might be pregnant. Stiller went ballistic.

“You fucking idiot. Is it not enough that you’re riding that hag Augusta?”

No one would ever buy into a movie star who was saddled with a wife and kids. Was that what he wanted? To be domesticated? If he went ahead with these relationships, Stiller would dump him completely. Worse still, Bergman was withdrawing his affection. It came as no surprise when Nils had a breakdown.

The Real Reason Visiting Hours Are Restricted

“I was an ambitious hunchback not worthy of anyone’s love. No one has ever loved me, and it’s certainly my hideous failure. Why was I such a vindictive and obnoxious person? Was it perhaps my hideous childhood filled with hymns, beating and screams that characterised me?”

Nils retreated to a sanatorium at Saltsjöbaden where he was the youngest by about seventy years. Whether he was off the magic fairy dust at this time was unclear, but he still managed to make another of his trademark disastrous decisions by having a girlfriend over to visit. They conceived a child on the ward.

She miscarried, much to their mutual relief, and they celebrated… by getting pregnant again. They fell out and she went to Switzerland to give birth alone. If he was remotely interested in his child, he doesn’t let on.

If you’re thinking it’s about time his mother gets involved, you’d be right. He arranged to meet with Hilda Asther for the first time since running away. The poor woman looked broken. Anton had set up with another lady and was raising a new family. Nils urged Hilda to divorce him, and promised to support her for the rest of her days. To prove it, he handed her a wad of banknotes. Probably Hjalmar Bergman’s banknotes, but the sentiment was sound. He still couldn’t bring himself to ask her about his adoption. In his mind, she was his foster mother, and she loved him in a distant way that was the best he could hope for. With all his relationships, Nils seemed to have seen himself as someone merely passing through. He never imagined anyone could truly become attached to him.

But where could Hilda go? The Asther house in Malmö wasn’t hers. And Nils surely couldn’t put her up in his sugar daddy’s apartment.

Nils knew just the place.

[Cut to the freshly-divorced Hilda Asther setting up home with Augusta Lindberg.]

Okay…?

I translated Nils Asther’s autobiography from Swedish so you don’t have to.

Because I love a gorgeous tragic dead boy, and people who’ve read it say it’s a car crash from start to finish.

How?

I can’t read Swedish. But I downloaded a translation app and know a couple of Swedes who helped me when Swedish idioms came out garbled and hilarious. The majority of the book was perfectly readable, even when I needed to make some leaps of logic to complete sentences.

And yes, it’s a scream from beginning to end.

Who?

Nils Asther is probably best known for his titular role in Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen. He had a long career, stretching from the First World War up to the 1960s, though his talent was mainly wasted on flimsy romantic roles. “I quit because I couldn’t stand making those ‘pretty boys’ films in uniform any more,” as he put it. His Swedish accent made him difficult to cast when the talkies came along, but his unusual beauty meant he stayed in demand for a long time, despite his open disdain for the film industry. Women were wild about him. Men, too. One male fan left the actor a fabulously expensive ring in his Will, a posthumous declaration of desire.

I mean, it’s little wonder.

Hollywood marketed Nils as a mysterious Scandinavian, an intellectual, an adventurer, and friend of Lenin for some reason. But in his memoirs, Narrens Väg (meaning ‘The Fool’s Way’), Nils looks back at the truth of his life (and I’m using ‘truth’ very loosely here) with bitterness, hilarity, and a ridiculously long list of lovers. How he found time for filming is beyond me.

Anyway, I thought it would be fun for other silent film fans if I summarised the fun bits in English.

Strap In, This Is Going To Get Bumpy

Once upon a time in Denmark, on a cold and dreary day in 1897, a boy was born to parents unknown. The child spent his first few months in a notorious orphanage until he was adopted by a beautiful, melancholy Swedish lady and her wicked husband who took him home to their big house in Malmö.

Once upon a time in Denmark, on a cold and dreary day in 1897, a boy was born to parents unknown. The child spent his first few months in a notorious orphanage until he was adopted by a beautiful, melancholy Swedish lady and her wicked husband who took him home to their big house in Malmö.

Or not. Once upon a time, a boy was born to Hilda and Anton, one-time lovers who had grown to despise each other. To conceal her shame, Hilda gave birth in Denmark and left her son in an orphanage temporarily to give her and Anton time to arrange a ‘colossal’ wedding that neither of them wanted.

They didn’t tell their son any of this. That would have taken the fun out of the next eighty years.

Despite his timid, bookish demeanour, little Nils Anton Alfide Asther was branded The Bad Child from the start. His elder half brother, Gunnar, was favoured in all things, and Nils and Hilda were largely left to their own devices, eating alone, vacationing alone, and trying to smile when Anton’s business partners came over, boasting about their money and their mistresses.

It seems everyone knew Nils’ shameful origins except him. The parish priest harboured a special dislike for the boy, making Sundays an ordeal he would later turn into gruesome art. (I’ll be sharing this painting later. It’s… something.)

Anton and Hilda’s marriage was poison. Neighbours whispered about the couple’s wedding night, when Hilda was seen trying to hurl herself out of a window. Relatives were concerned when she named her baby boy after her brother who brought shame on the family for sleeping with a maid. Hilda’s father beat the teen so badly – in front of the other children – he later killed himself.

So far, so horrifying.

Nils recounts his early memories like a series of battles. As a small boy, he walked in on his father violently assaulting his mother. She proceeded to use Nils as a human shield, which cemented in Anton’s paranoid brain that his wife and youngest son were in cahoots against him. Another night, Nils and Hilda barricaded themselves into a bedroom while Anton beat on the door with a gun.

It sounds like a melodrama from the silent films. And yes, Nils is probably embellishing. But decades before writing his memoirs, Nils gave interviews in Hollywood telling of how his main memories of Sweden were his mother crying alone in large rooms, and of being stunned when strangers treated them with kindness. The little details, like hardly daring to breathe when a certain floorboard creaked, ring true for survivors of abuse. After leaving Sweden, Nils never spoke to his father or half-brother again.

The domestic power-balance changed when Nils hit his teens. He shot past six foot, way above his father, and the physical difference made him realise he wouldn’t always be under Anton’s tyranny. Hollywood would later work hard to promote the shy, romantic teenage Nils over the self that emerged during this period, the one who was breaking windows and discovering boys.

Expulsion Number One – The Pekinese

We all had that one teacher we wanted to murder. For Nils, this was The Pekinese, a history teacher nicknamed for his unfortunate face and love of ‘biting’ boys with his cane. Nils liked the concept of history, but couldn’t absorb the names-and-dates nuts and bolts. It didn’t matter how hard Nils worked, The Pekinese just wouldn’t give him a break. His feelings for his teacher festered away along with the helplessness and frustration of his home life, evolving into a slightly manic hatred that would rear up again and again in later life.

One day in class, Nils was caught playing with a knife. That wasn’t a problem – all boys had knives – but he was using his to carve a willy into his desk. Inspecting the damage, The Pekinese discovered Nils’ cartoons – which, admittedly, were quite good – all depicting the teacher as an angry lapdog.

He was up against the board with his pants down in no time. The Pekinese got out his cane and delivered several sharp whacks. Refusing to show any pain, Nils waited until the final blow to peep over his shoulder: “Was that nice?”

The boys howled with laughter. Nils was mad with adrenaline. When this got back to Anton, he might actually die of rage. However, the headmaster showed a frustrating amount of leniency. You’re a smart boy, usually so well-behaved, you’re about to begin your leaving exams, etc, etc. He didn’t want to suspend him for something so silly as graffiti and cheek.

So Nils sawed two legs off The Pekinese’s chair and gave him concussion, just to make sure.

Expulsion Number Two – This Time, It’s Musical

When the yelling died down, Nils was sent away to the Spyken school in Lund. The school still exists and is probably lovely, but in the early 1900s, ‘The Spyk’ was where rich men sent their ill-behaved children when no one else would put up with them.

Things went well for a while. It was a relief to be away from home, even though he worried about Hilda being alone with Anton. But when a new PE teacher turned up – a short man with a chinstrap beard and dandy pretentions – that manic hatred boiled up again. The poor guy was doomed.

The gym was in the basement, and the boys had to file down a steep flight of stairs to get there. There was always plenty of larking about on the way, but one day Mr Chinstrap told them all to shut up and get in line. A strange compulsion seized Nils. It would be so much more fun to boot him down the stairs.

While the teacher lay clutching his broken ribs, Nils stood at the top of the stairs singing ‘Liten Karin’, a cheery Swedish folk song about a king who puts a maid into a barrel full of spikes and rolls her around until she dies.

Eesh.

Have A Screaming Match With Your Vicar In The Gym, Why Not

When you have a demon child on the premises, the only option is to call a priest.

Anton Asther stormed into the school, “roaring like a lion”. The headmaster called the family’s priest (the one who thought Nils was the physical manifestation of sin) and although the cleric’s presence stopped Anton from murdering his son, it was a life-changingly bad idea.

Most of Nils Asther’s memoir is about life-changingly bad ideas, honestly.

So they’re locked in a room together, just yelling at each other. Father Soandso attempted reason; words to the effect of “Why did you break your teacher’s bones again, you utter lunatic?” Nils stuck to his guns with a litany of “You lie, priest bastard!”, which is a great response to just about anything. This went back and forth until the priest gave up any pretence of Christian compassion or priestly discretion:

“How I wish my friend Anton had never let that woman persuade him into adopting you. We have reason to believe that you are the son of a whore and an adulterer in Copenhagen.”

Oh.

Now, if you’d just been told you were adopted, wouldn’t you go to your parents and maybe… ask them?

Or would you rather burst out of the room, grab your things and get the train to Stockholm without saying a word to anyone?

There was a little bit of reasoning behind this move. Not much. But a bit. To summarise:

I am not related to awful Anton.

I am also not related to my beautiful, sad mother.

But she probably doesn’t love me either.

So I’m going to become an artist.

Anton will hate that.

This all turned out to be another life-changingly bad idea.

What do artists do all day? Well, they hang around in cafes looking interesting. In Stockholm, Nils found a floor to sleep on and an old school friend to hang out with. The pair became a regular fixture of murky city nightlife. One evening, going out to eat, the teenagers were approached by man with gigantic hands and even bigger feet. The boys must join him for dinner, he said, definitely not leering. Had Nils ever thought about acting? Did he like films?

Nils had never seen a film. He certainly didn’t know he was talking to Mauritz Stiller, the man who discovered Greta Garbo. According to Anton Asther, actors were degenerate idiots who disgraced their families and died penniless.

So yes. Yes, he was interested…

TBC. Read part II here.

I’ve been talking to author Helen Barrell about her new book Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science out now from Pen & Sword.

Professor Taylor appears in your last book, Poison Panic, to deal with some murderous Essex wives. How did he capture your imagination sufficiently to make you devote a whole book to him?

Taylor was the expert witness in the 1840s arsenic poisoning cases which involved Sarah Chesham, Mary May and Hannah Southgate. He was called in to work on all of the cases, and the papers were calling him “the eminent professor”, so I wondered – who on earth is this man? Then when I discovered he’d been summoned by the police to analyse bloodstains during the investigation of Thomas Drory, the Doddinghurst murderer,– and that’s as early as 1850 – I was surprised and intrigued.

I quickly found out that he’d been involved in a huge number of cases, and not always as a toxicologist, although that’s how he’s best remembered. Coupled with this was his massive output of books and journal articles, and his own editorship of the London Medical Gazette. His personality comes out in everything he writes; he’ll start in scholarly tone, but he just cannot resist injecting something of himself. It might be an unscholarly expression of amazement, it might be a sarcastic aside at an enemy, it might be a jibe at how stupid some criminals can be.

So not only are there fascinating cases involving a vast cast of Victorians, you’ve got a clever, sarcastic professor and the evolution of a science. Writing Taylor’s biography was utterly irresistible.

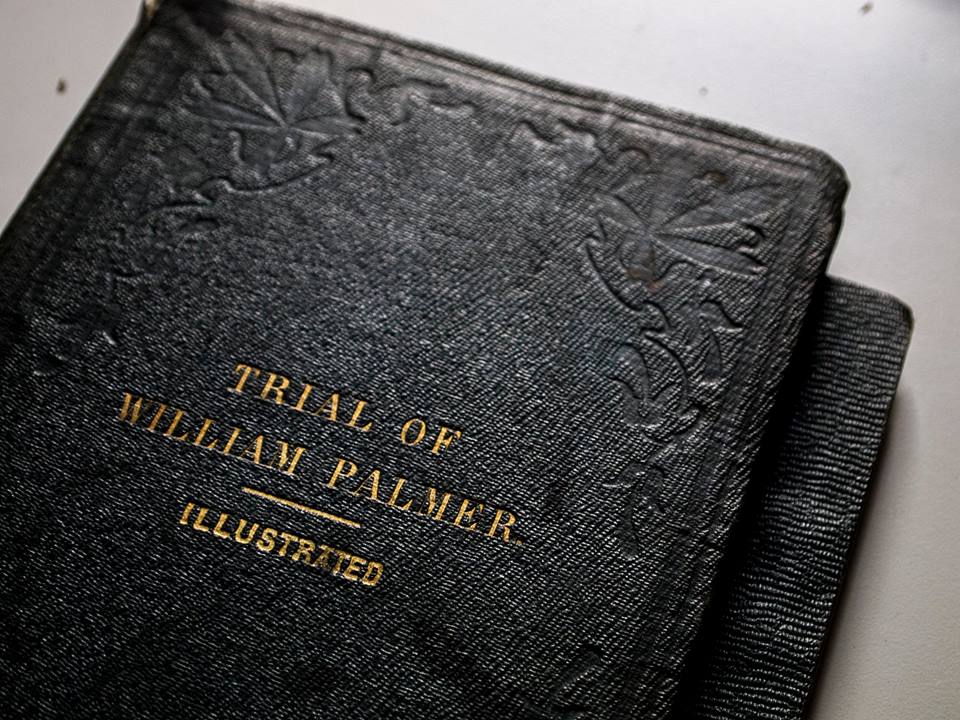

Victorian true crime enthusiasts will probably know Professor Taylor from the particularly nasty Rugeley Poisoner case. William Palmer, or ‘The Prince of Poisoners’, was a surgeon, and went to the gallows for his crimes. But that wasn’t the only time Taylor took down a fellow medical man for murder…

The Palmer and Smethurst trials are the only ones which Taylor worked on to be included in the famous red-bound volumes of the Notable British Trials Series. This is perhaps why Taylor is remembered almost exclusively for them, which means that nowadays his career is seen through a Palmer/Smethurst-tinged prism. But they were difficult cases, and Taylor himself harped on about them for years afterwards.

I have to say that researching and writing the 1856 Palmer cases gave me nightmares! I don’t live far from Rugeley, so my partner and I popped over on the train. We saw the pub where John Parsons Cook died, and I even went into the pet shop which occupies half of what was once Palmer’s house (I bought cat treats for my furry chums at home!). We saw the house where Palmer was born, and went to the church where Cook is buried and saw his grave. The stone was paid for by the priest who was the vicar at the time because so many people were visiting Rugeley purely thanks to the notorious Palmer, and along one side, almost buried now by grass and rising soil, is a line from Proverbs:

Enter not into the path of the wicked. Avoid it, pass not by it, turn from it, and pass away.

That night, I had a terrifying nightmare. I was in the churchyard at Rugeley in the twilight, and there was a horrible sense of evil in the air. I heard someone chant, over and over again, a line from the Lord’s Prayer: Deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil….

I managed to develop anaemia at the time, too, and so it felt like William Palmer was trying to finish me off as well! But it has to be said – when you’re writing about crime, real people died sometimes horrible deaths, by “unfair means”, as the Victorians used to phrase it. Although I found the Palmer chapter emotionally hard, I was relieved in a way because it meant that I hadn’t become desensitised.

But to move on to the other medical man who Taylor found himself toe-to-toe with, that would be Dr Thomas Smethurst.

These days, the jury is very much out on the 1859 Smethurst case, as some people think that Isabella, his “wife” whom he was accused of murdering, could have died from Crohn’s disease, or a similar intestinal complaint, aggravated by pregnancy. It was thought at the time that Smethurst used his medical knowledge to bump Isabella off.

Smethurst had originally married a woman who was 22-years his senior. While she was still living, he and Isabella Bankes, an heiress with an annuity, were carrying on with each other in the genteel lodging house where Smethurst was living with his first wife. Isabella was asked to leave by the landlady, and Smethurst quickly followed her. They were bigamously married, and not long afterwards, Isabella fell ill.

She had several doctors, besides her husband, caring for her, and all of them thought that something was off. One Sunday, Taylor was visited at home by a doctor bearing Isabella’s stool samples. Taylor lived in a on well-to-do Regent’s Park – one wonders what his neighbours made of the police and medical men who would drop by with articles for him to examine. On analysing one of the samples, Taylor found arsenic, and declared that Isabella was, quite likely, being poisoned, so her “husband” was arrested. Soon afterwards, she died.

Smethurst was a quack. He had a large collection of homeopathic remedies, and he had run a hydrotherapy spa in Surrey, which Dr Lane bought from him – in case that sounds familiar, Dr Lane was embroiled in the scandalous divorce case of Mrs Robinson. It’s very clear from his time as editor of the London Medical Gazette that Taylor had zero patience with quackery, and he had to examine all the homeopathy bottles looking for arsenic, and also antimony, which he found in Isabella’s body. Antimony wasn’t unusual in medicines, and arsenic was found in some as a pick-me-up – the risk was that Isabella could have been poisoned by one of the many remedies that Smethurst had in his possession. Or indeed, that so many bottles were an excellent way to hide the source of the arsenic, if Smethurst hadn’t already jettisoned it.

One of the bottles was mysterious to Taylor. It was almost empty and he only just managed to perform his favourite arsenic test – the Reinsch test – on it. It tested positive for arsenic, and he said that this was the likely source. Unfortunately, just before the trial, Taylor realised that he had made an error. The arsenic had in fact come from the copper which was part of the Reinsch test, and the mystery bottle had contained a chlorate which dissolves that metal. The arsenic in the copper gauze was released because the chlorate had dissolved it.

Taylor owned up to this error, and tried to turn it to his own ends as a scientific discovery. Well, every cloud has a silver lining, I suppose. The jury still found Smethurst guilty of murder, but he mounted an appeal. Newspapers groaned under the weight of people who had an opinion on the trial – it wasn’t only Taylor’s problem with the copper that some quarters of the public found fault with. Wilkie Collins lampoons this in his 1864 novel Armadale, concerning the trial of Lydia Gwilt, who was:

‘tried all over again, before an amateur court of justice, in the columns of the newspapers. All the people who had no personal experience whatever on the subject seized their pens, and rushed (by kind permission of the editor) into print. Doctors who had not attended the sick man, and who had not been present at the examination of the body, declared by dozens that he had died a natural death. Barristers without business, who had not heard the evidence, attacked the jury who had heard it, and judged the judge, who had sat on the bench before some of them were born.’

Smethurst’s sentence was overturned. However, he was tried for bigamy and sent to prison anyway.

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Professor Taylor had some fantastic interactions with the luminaries of the day. Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins were fans, but Sir Arthur Conan Doyle went so far as to base a character on him?

I was very excited when I found a list of all the books in Wilkie Collins’ library (I’m a librarian, so this thrill should not come as a surprise) and was pleased to see that Collins had owned not one, but two editions of Taylor’s On Poisons. It’s safe to say that whenever you see any poison turn up in a Collins’ novel, he’s probably drawn on Taylor’s extensive research and compiled cases to inform his writing.

Charles Dickens was such a fan that Taylor gets mentioned several times in his magazines, and at one point Dickens even visited Taylor’s laboratory at Guy’s Hospital and was given a tour. Imagine Dickens, who seems so cosy now, gazing in amazement at flakes of human liver in a jar, and a stomach in a fume chamber.

And it’s entirely possible that Taylor is one of several men whom Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was thinking of when he created Sherlock Holmes. It’s well-known that Conan Doyle admitted to basing Holmes on one of his tutors at Edinburgh Medical School, Dr Joseph Bell, and he also said that Poe’s detective Dupin was an influence.

However, if you read Dr Watson’s first meeting of Holmes in A Study in Scarlet and you know about men like Robert Christison (another Edinburgh Medical School Man, and a near-contemporary of Taylor’s) and Taylor, then it seems like Conan Doyle is deliberately referencing them in the character of Holmes. Watson’s friend tells him that Holmes has been ‘beating the subjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick’ which is a clear reference to experiments Christison carried out during the trial of Burke and Hare in 1828. He talks about Holmes experimenting on himself and friends with poison, and Christison had written about how he and his scientific chums had put arsenic on their tongues to discover if it had a flavour.

When Watson first sees Holmes, he’s just that moment discovered ‘an infallible test for blood stains’. The famous amateur detective puts a plaster on his finger, where he had pricked it to draw his own blood, saying, ‘I have to be careful, for I dabble with poisons a good deal.’ Blood stain and poison analysis? This sounds rather a lot like Taylor.

And there’s also Taylor’s height, which was often commented on. His energy, and his biting sarcasm to anyone who had the temerity to disagree with him, all seem rather Holmesian. Conan Doyle mentions the Palmer trial in The Adventure of the Speckled Band, and refers to one of Taylor’s books in The Stark Munro Letters; Conan Doyle’s semi-autobiographical novel about a freshly qualified doctor trying to find his feet. Although Holmes might not use his test-tubes very often, they are often a feature in the background, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if this is partly Taylor’s influence.

Taylor almost knew of Conan Doyle. In 1879, the year before Taylor’s death, ‘ACD’ wrote a letter to the British Medical Journal about some self-experimentation with a flower used for curing headaches. Taylor was providing editorial for the BMJ at the time, and so he’s very likely to have read Conan Doyle’s letter. What he made of it we cannot, of course, now know.

And he had a bit of a reputation for… well, losing his temper.

The article Taylor wrote after the Palmer trial is extraordinary piece of work; the toxicological equivalent of a schoolboy thumbing his nose and chanting “neener-neener”. It drips with sarcastic rage; he carefully collated other cases and provided a chart showing aspects of strychnine poisoning, but the footnotes are full of exclamation marks, barbed comments and even sarcastic schoolboy Latin.

He loathed Henry Letheby and William Herapath – expert witnesses hired by the defence at the Palmer trial – and to be honest, they loathed him in return. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the animosity began, although it could have started off as professional jealousy – they were working in a new field and were trying to convince the public of the import of their work. After the 1845 Tawell trial, when a woman had been murdered after drinking stout laced with cyanide, there were irate letters in The Lancet between Letheby and Taylor – Letheby was most annoyed that Taylor, who hadn’t been one of the expert witness at the trial, had conducted his own experiments (could you smell cyanide’s distinctive almond scent when mixed with alcohol?) and written about it in an article on cyanide poisoning. He was really very rude about Taylor; although he didn’t name names, he stated that some people were writing about cyanide ‘to gratify the cacoethes scribendi’ (insatiable desire to write), which is clearly a jibe aimed at Taylor.

The sniping that went on between Taylor and the men who ruffled his feathers is hilarious – it’s just like today when you see academics arguing on Twitter. If Taylor was alive now, that’s exactly what he’d do all the time, I’m sure of it!

He would fly into a fury over public health matters too – he appears to be the first scientist to go public with the surprising idea that arsenical wallpaper dyes might just be a bit dangerous. He was roundly disbelieved, and arsenical dyes continued to be used in the face of mounting evidence from scientists.

I remember you telling me about having to gently explain saponification to your editor. You even have a section called ‘A Horror of Bad Smells’! Without ruining everyone’s dinner, what’s the single grossest thing you’ve come across in Professor Taylor’s career?

This is such a hard question to answer –there’s a heck of a lot of gross things in Fatal Evidence (I did try to avoid too many details though, but it’s possibly not a book to read over lunch), and it’s impossible to mention them without turning people’s stomach. Sorry chaps!

So move along, unless you would like him analysing tapeworms that he found in the intestines of an arsenic poisoning victim. Or would you like the theory one doctor had, that Mrs Wooler was being poisoned with arsenic up her bottom via enema syringe? How about his examination of people who had been dead for some while, whose bodies had turned to soap such that the individual organs were unrecognisable, and yet he was still tasked with analysing them? One of these saponified corpses took him a week to examine and he wrote a letter to the Coroner who had hired him, to complain of the terrible headache the analysis had given him – and the letter, which did not hold back on gory details, was deemed worthy of reproduction in the newspapers!

I imagine you yell at the TV when a Victorian detective squints at a corpse and whispers “Arsenic!”.

Let’s just say I had problems with Taboo and the twenty-minute arsenic test in 1815. In 1850, with the far more efficient Reinsch test, Taylor took half an hour at a trial to analyse a bag of white powder. Now – would it be at all plausible that several years earlier, with a less efficient test, someone was able to examine human organs for arsenic – in twenty minutes? I think not.

This is your second book, and a natural progression from Poison Panic. As a writer, what have you learned about the process from that first experience?

In terms of purely practical things, sort yourself out with a nice place to sit. I wrote Poison Panic on an ancient laptop at the dining table, and ended up hurting my shoulder because I was hunched over. As I knew Fatal Evidence would be a longer book, and would require lots of research, I treated myself to a desk and a PC. And I wrote Fatal Evidence on Scrivener – it made life a lot easier.

There was such a lot of research required for Fatal Evidence, so I used a couple of spreadsheets to keep track of it all. I’ve got a massive timeline showing all of the cases I could find in the British Newspaper Archive which involved Taylor, and ones that I spotted from other sources such as his books and articles – I didn’t use all of them in Fatal Evidence, and I’m certain there’s still cases that are out there somewhere which I wasn’t able to find. I felt very organised, although I’ve still got a massive storage box next to my desk filled with box files of research! I’m loathe to chuck it all out, but I’m not sure where to put it.

I have to say that while I was writing Poison Panic, I was beset with fear that I’d never actually finish it. I was almost frozen sometimes by Imposter syndrome, thinking that I was rubbish and incapable, and that surely someone somewhere had made a mistake because I just couldn’t do it. But I kept going. So when I came to write Fatal Evidence, whenever that feeling tried to raise its horrible head again, I could face it down by going, “I’ve finished one book, I’ll finish this one too!” I wasn’t panicking as much, which made the process less painful – anaemia and nightmares excepted!

And I can’t really finish without saying you’ve upped your costuming game from last time. Nice tailoring.

Thank you! The irony is that my professor outfit is technically cross-dressing, seeing as I’m dashing about as a Victorian chap, but it’s much closer to what I wear on a day-to-day basis than the Victorian lady’s costume I had for Poison Panic last year! I wear a Walker Slater tweed waistcoat with trousers to work, and when the weather’s cooler, I’ll wear my tailcoat too. That said, I don’t wear a cravat or Mr Darcy shirt to work – perhaps I should.

Thank you, Helen!

Fatal Evidence is a worthy successor to Poison Panic, and a must for true crime fanatics. Don’t forget to follow Helen on Facebook for regular updates on her research.

1840s Essex was a tough place to call home. If the damp cottages or the Potato Blight didn’t kill you, your wife might take the hump and lace your porridge with deadly poison.

This is the grisly focus of the new true crime book by Helen Barrell, Poison Panic: Arsenic Deaths in 1840s Essex.

I’ve talked to Helen about death and domesticity in 1840s Essex…

What drew you to poisonings as the subject of your first book?

I grew up reading Arthur Conan-Doyle and Agatha Christie, so when I tripped over a real-life poisoning case, I was fascinated. I had been transcribing the burial register for Wix in Essex, as part of my genealogical research, and there it was – some poor chap who’d been poisoned by arsenic. As a lot of my family are from that area, there was a chance that I was related to him, and so I started to dig deeper. With the British Newspaper Archive, there’s so many newspapers digitised and easy to access, so I was able to read the inquests and trials. Being a genealogist, I was able to reconstruct the families of the women who were accused of the poisonings, which is a new angle that hasn’t really been explored before.

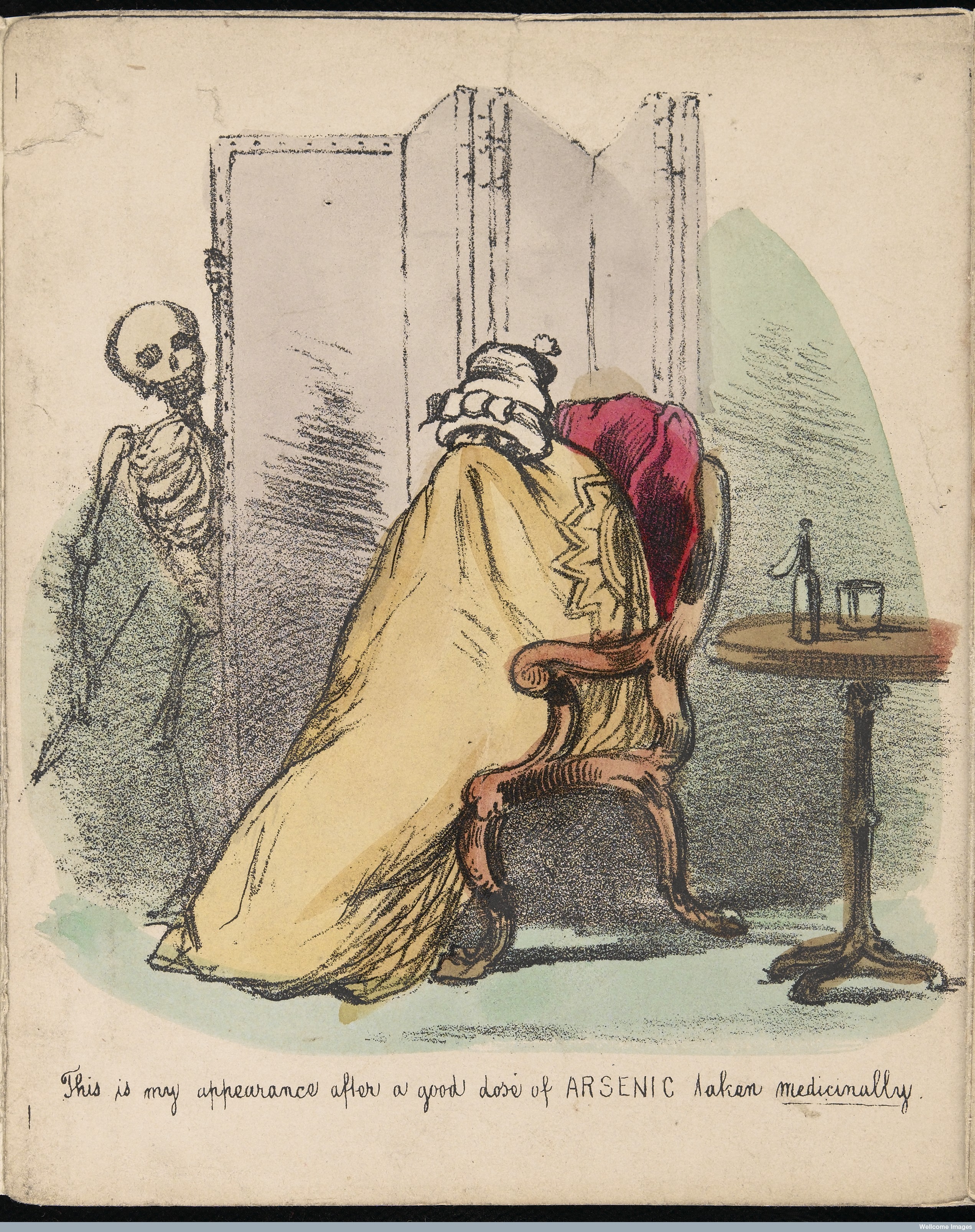

Arsenic poisoning is a terrible way to die, but that didn’t stop Victorians from using it around the home. Of the many 1840s uses for arsenic – disposing of a bad husband aside – which struck you as the most alarming?

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

But I think what shocked me most was how casual they were about using arsenic in conjunction with food. You could become poisoned by it if you absorbed it through the skin, but the most common way was by it entering your mouth. So if you’re trying to deal with rodents plaguing your badly maintained cottage, putting arsenic on bread and butter to attract the vermin might seem like a good idea. But if you’ve got a house full of people, it’s just possible that someone might accidentally die. Especially as arsenic used in the home was often ‘white arsenic’ and resembled flour.

What alarmed me more, though, was that arsenic-based green dyes (Scheele’s Green) were used in food colouring. And yes, it killed people. In 1853, two children died eating the green ornaments on their Twelfth Night cake, and in Northampton in 1848, one man died and several others fell ill after eating a green blancmange. The shopkeeper who sold the dye for the blancmange was convicted of manslaughter – why? Because it was felt he hadn’t explained the safe dose clearly enough.

“He’s in the burial club” was Victorian slang for ‘he’s not got long to live’. Tell us about these these burial clubs and how they tied in to the 1840s poison panic.

I’m sure you’ve heard of the case of Burke and Hare, the Edinburgh-based resurrection men who, rather than dig updead bodies, killed people to provide Edinburgh Medical School with cadavers. Following that scandalous case, it was decided that Something Must Be Done. As long as it didn’t involve dead middle- and upper-class people being cut about by medical students; after all, the faithful believed that an anatomised body couldn’t rise from the grave on Judgement Day (though somehow bodies reduced to bones and dust could). So Edwin Chadwick, that enemy of the poor, came up with a brilliant plan. How about parishes, which were more or less the local councils of their day, selling their dead paupers to medical schools when they were in need of a body. So if you died, and your body was unclaimed by family and friends because they couldn’t afford to bury you, you could end up the subject of an anatomy lesson – the poor weren’t allowed agency over their own bodies.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

Except burial clubs were run by self-organising workers, usually meeting in pubs. So for instance, in Great Oakley in Essex, you had the Maybush Burial Club, which met at the Maybush pub – that pub is still open. Landlords liked to get involved as they could convince the funeral party to have a knees up at their pub. But they weren’t very secure, and they were unregulated, which meant that you could pay into a club for several years, and then when Little Eleazar went the way of all flesh, the club has packed up and can’t payout. So people would enter family members in more than one club at once. But then there was a problem – what happens if the clubs are in fine fettle when Little Eleazar’s cough turns bad, and you get a £10 payout from four different clubs? You’ve suddenly got £40 from your son’s death. Edwin Chadwick decided that some parents were entering children in multiple clubs and then murdering them, just for the burial club money. It’s a version of the life insurance murder, which would reach its most infamous moment at the trial of William Palmer in 1856.

Mary May, who lived in Wix, had entered her half-brother William Constable (also known as Spratty Watts), in a burial club in Harwich. He died a month later. The local vicar, Reverend George Wilkins, was suspicious, especially as Mary kept pestering him to write notes for the burial club, as they wouldn’t pay out. There was an inquest and it was discovered that Constable had died of arsenic poisoning. But had Mary May really murdered her own brother for £10?

In the 1840s, how could an investigator attempt to detect arsenic in a suspected poisoning case? How accurate were these early forensic techniques?

I’ve been doing lots of research into this for my second book – it’s quite interesting. Sometimes the investigator would be able to see arsenic with the naked eye: either in white lumps, or yellow orpiment. This was caused by arsenic oxide (white arsenic) reacting with the sulphur being released in the body after death, creating arsenic trisulphide. In one case, Professor Taylor asked one of the illustrator at Guy’s Hospital, where he worked, to produce a colour drawing of the deceased’s stomach, and use the arsenic trisulphide with gum to show where he had found the poison in the body. Not quite something you’d see in a courtroom now, but I suspect Taylor would’ve embraced colour photography if it had existed in his lifetime.

They would also look for backup evidence – the symptoms of poisoning were important, partly to indicate what they had been poisoned with, but the onset of symptoms would indicate when the poison had been administered, and might point you in the direction of the culprit. It could even lead you to realise it was an accident. But then you had the problem that poisoning symptoms, such as those of arsenic, weren’t unlike the gastric upsets that were common in a world with poor sewerage systems. It just wasn’t possible to open an inquest for everyone who died of violent vomiting and diarrhoea, as it would upset the county ratepayers who footed the bill for Professor Taylor.

In the early 19th century, they had to rely on a battery of tests. In some forms, arsenic would smell of garlic when it was heated, but this was clearly unreliable as it relied on the chemist’s sense of smell. There was the reduction test, which was a bit more reliable, but you needed to have a decent about of arsenic present for it to work. You heated arsenic oxide (white arsenic) in a tube, which released the oxygen and turned it into a metal. If you were testing a liquid, you used hydrogen sulphide to make arsenic trisulphide. The remaining oxygen reacted with the hydrogen and created water, then you could perform the reduction text on the arsenic trisulphide. There were reagent tests as well, which relied on the known reactions of arsenic with other chemicals, but they were unreliable when there was, how shall I put it, organic matter present, which would affect the colour changes.

So in 1836, James Marsh came up with a test involving hydrogen and zinc, which forced arsenic out of liquids. You’d hold a piece of cold glass over the end of the tube and as the highly poisonous ‘arsenuretted hydrogen’ (or arsine gas to you and I) came out, the arsenic would deposit itself on the glass in a convenient metallic film. You could then use the reduction and reagent tests on the metallic film; the test would also dislodge other poisons such as antimony and mercury, so you had to rule those out.

In the early 1840s, Hugo Reinsch’s test took over from Marsh’s. It used simpler equipment – you added hydrochloric acid to your suspicious liquid, and dipped in some copper. Any arsenic present would appear on it, again, as a metallic film, and the other confirmatory tests could be performed.

The Marsh and Reinsch tests were far more sensitive than the previous methods available, but this could lead to embarrassing mistakes, such as eminent French chemist Orfila claiming that arsenic was a natural constituent of human bone. When he used the Marsh test on bone, a metallic film resulted, but far too small for him to carry out any confirmatory tests. It’s possible that the arsenic found in the alleged victim of Madame Lafarge, which Orfila used the Marsh test to investigate, actually came from the pots his corpse was boiled up in, or the acids that were used as part of the process.

If you’re dealing with someone who’s been killed with a large dose of arsenic, the Marsh and Reinsch tests are probably quite reliable – as long as the chemist has checked their apparatus, their zinc, and copper, and acids for any contamination. But it’s when the amounts are small that there’s a problem and it seems less reliable. When Sarah Chesham’s husband died, Taylor found a tiny amount of arsenic inside him – in 1859, he wrote that it was the smallest amount he’d ever identified. But he was clear with the prosecutors – it was too small an amount for Sarah to be charged with murder. Bearing in mind the problem he ran into later in 1859 with the Smethurst trial, I have to wonder if the arsenic Taylor found in Richard Chesham’s insides was from Taylor’s laboratory apparatus, rather than a dose administered with murder in mind.

How did the press handle the idea of women murdering their husbands? Do you think Southgate, May and Chesham’s cases would be approached differently by today’s tabloids?

The first thing that struck me about the way they reported the cases was how they described the accused. These days, people in news stories are described as ‘mother of two’ or ‘a grandmother’ – and the same goes for how they describe men, even if the news story that follows has no bearing on whether or not they’ve managed to reproduce! Anyway, in the 1840s, the newspapers would define you by your social status. So the women in Poison Panic, the women were described as ‘wife of an agricultural labourer’ or ‘wife of a farmer.’

And then there’s the women’s appearances. When women were found not guilty, the newspaper describes them as beauties, and women sent to hang are described in highly unflattering terms. At the execution of one of the women in Poison Panic, the papers commented on the fact that her stoutness meant her hanging was swift; it seems such an unseemly thing to comment on, but it’s an extra indignity piled onto an already wretched end. Newspapers still make a big fuss about women’s appearances, more so than men’s.

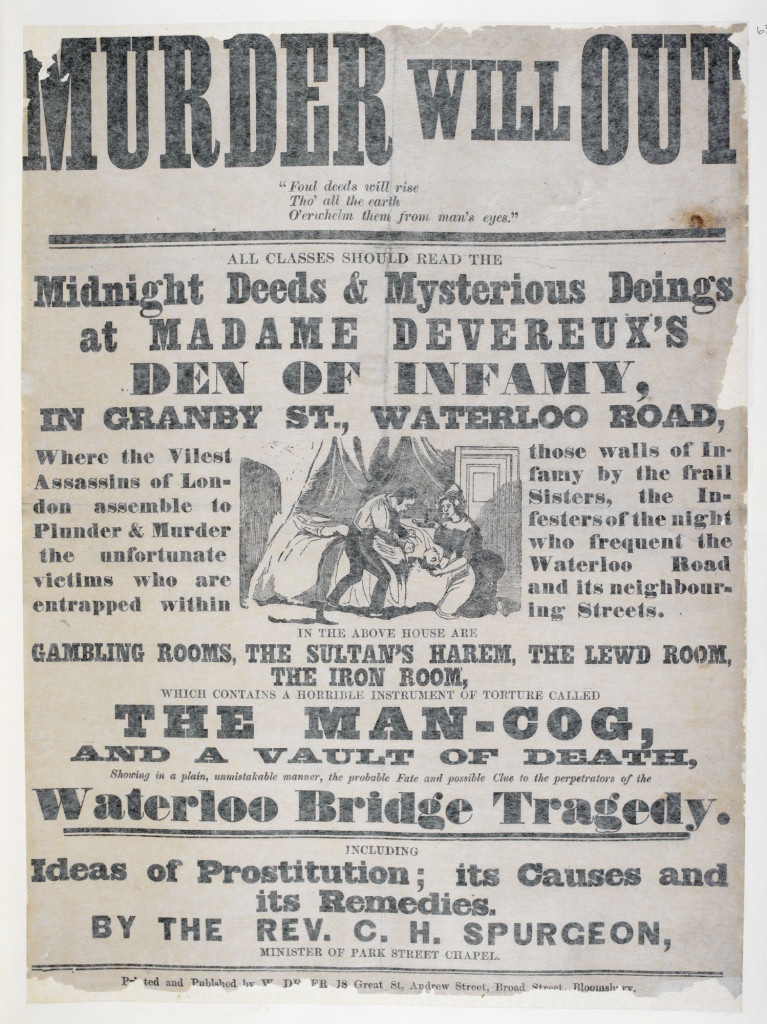

Victorians adored a good murder. How did these sensational crimes filter down into the popular culture of the day?

Public executions drew big, rowdy crowds, so if you wanted to make some money, just print up some doggerel verse with the name of the condemned shoved in any old how. It doesn’t even have to rhyme that well, and it certainly doesn’t need to scan. It wasn’t unusual for people to use execution ballads as their newspapers, as some were sold house-to-house, or in the streets, which is problematic as the ballad-sellers didn’t make much attempt at factual accuracy.

If there was a particularly sensational trial – such as that of Thomas Drory, the Essex farmer who strangled his heavily pregnant lover – the ballad-sellers really went to town. You could buy an illustration of Drory murdering Jael Denny; you know he’s bad because they gave him a melodrama villain’s mustachios. What a lovely souvenir.

Executions had previously taken place only a couple of days after sentence was passed, so there wasn’t much time for them to prepare their ballads. As one ballad-seller explained to Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor, “There wasn’t no time for a Lamentation; sentence o’ Friday, and scragging o’ Monday.” But by the 1840s, there would be several weeks before the hanging, so they could print multiple confessions, lamentations, and ‘true histories’ (which were anything but), ensuring that it wasn’t just William Calcraft who earned a pretty penny from a hanging. Sorry, ‘scragging.’

You’ve invested in a pretty fantastic Victorian outfit. Can we hope to see you out and about in it?

I’ve always loved dressing up in historical costume, probably because I was taken to Kentwell Hall at an impressionable age! So when the chance came up to have my own made-to-measure 1840s dress, it had to be done.

I’ve been a fan of the Brontës for a long time, and at one point was considering a postgrad research project on them. I’d been researching the 1840s, which is another reason why finding that burial record from 1848 was somewhat fortuitous! And seeing as it’s the 200th anniversary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth – which, I feel I must say, has been overshadowed by the anniversary of that playwright bloke’s death – getting my bonnet on seemed only right.

I shall indeed be scuttling about in it; quite frankly, whenever the opportunity arises.

And finally, tell us about your work in progress, Fatal Evidence.

And finally, tell us about your work in progress, Fatal Evidence.

The name “Alfred Swaine Taylor” runs through Poison Panic like “Clacton” through a stick a rock. He’s the expert witness in nearly all the cases in my book, and although he’s mainly remembered as a toxicologist, he was involved in the Drory case because he identified bloodstains on clothing, and could comment on strangulation. He gets called ‘the father of English forensic science’ quite often, as well he might, but no one had written a book-length biography of him. So Fatal Evidence is a balance between Taylor the public man, in his laboratory and in the witness box, and Taylor the private man, in his home in Regent’s Park, borrowing his wife’s lace to experiment with photography. It’s fascinating – all the different cases he worked on, and all the ridiculous things scientists did then. Taylor only became Professor of Chemistry at Guy’s Hospital because his predecessor accidentally blew himself up when experimenting with compressed gas, and Taylor’s Scottish counterpart, Robert Christison, found out that arsenic didn’t really have a flavour by putting it on his own tongue! That will be published next year – I’ve already started looking for a cravat.

Poison Panic is published by Pen & Sword at the end of June, and available for pre-order now.

Two days until Halloween! Which means there’s still time to acquire some 100% natural dark circles around your eyes. Maybe she’s born with it; maybe she’s too scared to sleep. I’ve been meaning to do a book recommendation post for a while, so here are some scary stories to give your cheeks that desirable rosy glow. White roses. Dead ones.

Susan Hill is one of our finest living ghost story writers, and Dolly is the tale of what happens when children go bad. Brief enough to be read in one sitting, Dolly takes the old spooky doll trope and shakes it by the shoulders.

I love Peter Ackroyd. I love hulking London churches. And I love a nice occult murder conspiracy. Ackroyd has a way of presenting jump-scare moments so coolly, the reader is totally taken by surprise. He’s still one of the few horror-esque authors who can genuinely thrill me.

Photographs of abandoned Arctic whaling stations are terrifying, let alone having to live in one, alone, when you know the sun isn’t coming up for months. Part paranormal horror, part solitude survival story, Dark Matter is a genuinely refreshing, tense book with a vivid sense of place.

A Good and Happy Child

We were all lonely children, right? And we all wished for a friend. George Davies lived to wish he never had.

The Quick

The Quick is for vampire lovers. ‘Enter the rooms of London’s mysterious Aegolius Club – a society of the richest, most powerful men in England’. I want more from The Quick’s universe – it feels a natural springboard for short stories and sequels.

The Haunting of Hill House

“No live organism can continue to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality”. Shirley Jackson is the master of the haunted house story. It’s a classic. Go and read it.

Have a pleasurably traumatic happy Halloween, friends! And recommend me some books in the comments.