TW: frank discussion of suicide and domestic violence, including images. Spoilers for season one and two of Our Flag Means Death.

It’s fiction: it doesn’t matter.

It’s fiction: it matters more than anything.

The two wolves inside of me are warring this week.

For eighteen months, I’ve been a huge fan of HBO’s Our Flag Means Death, a workplace pirate comedy where everyone is some flavour of queer and the watchword is kindness. The cruel old tropes are consciously thrown out in favour of inclusivity, raucous jokes, and tearjerking romance, while imperfect, middle-aged queers fail at everything they try, dust themselves off, and try again.

As wealthy landowner Stede Bonnet embarks on his new life as the Caribbean’s most useless pirate, he plants his hands on hips and says. “Piracy is traditionally a culture of abuse. My question is, why?”

Kindness. Always that word, from the cast, the writers, and the show itself: kindness.

I guess that’s why I feel so blindsided by season two.

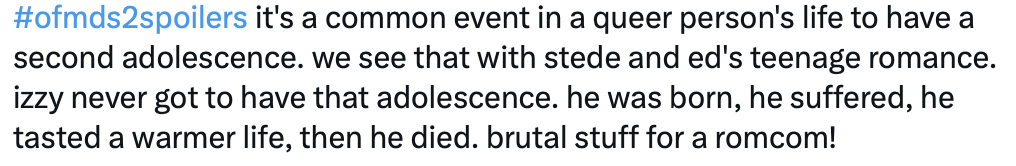

This silver fox is Izzy Hands, based on the real 18th century pirate Israel Hands, Blackbeard’s (allegedly) 16-year-old right hand man, and the only member of that pirating circle who lived to tell the tale. The real Israel Hands was shot in the knee in a moment of Blackbeard’s classic mania. He kept the leg, but was disabled for the rest of his life – possibly another 16 years or so, if some records are to be believed. Israel was immortalised in Treasure Island, and now Our Flag Means Death.

OFMD‘s Izzy is a little older than Blackbeard. He’s the legendary pirate’s first mate, and de facto wife. When we first encounter him, he’s exhausted and frustrated, worried about the captain’s increasingly erratic moods, but firmly believes Blackbeard is “the greatest sailor I’ve ever met”. Izzy is a buttoned-up old-guard leatherman, strongly coded as autistic, who just wants to run a tight ship and enjoy the safety and prestige afforded by the Blackbeard brand. He frets about the crew dying for Blackbeard’s whims, and when Blackbeard falls in love with Stede Bonnet, who knows nothing about piracy but fancies having a go anyway, Izzy sees Blackbeard’s downfall on the cards and panics. Izzy spends season one doing everything he can to keep Blackbeard away from Stede and the incompetent crew of the Revenge, but in the end, he doesn’t need to – Stede loses his nerve and abandons Blackbeard, returning home to his wife in Barbados.

Izzy also tries to leave. This is important. He apologises for his emotional outbursts, tells Blackbeard he supports his plan of retiring from piracy, and packs his bags. Blackbeard, unsure of what he wants, wheedles Izzy into staying. “I need you here,” he says, with a tender touch that sends a shiver through Izzy’s whole body. This is a man helplessly on the hook.

Izzy’s increasing exasperation is like watching a Black Sails character forced to interact with a dozen Muppets. His every attempt to get back to actual pirating blows up in his face. His seasickness is legendary. He gets hit in the face by a flying sandwich (a scene they had to film nine times) and peppers his speech with more expletives than the rest of the crew combined. But Izzy is essentially a tragic character, a jilted spouse who can’t believe he’s losing his man to a buffoon like Stede Bonnet. Izzy’s wariness of Bonnet’s out-and-proud Revenge crew struck a chord with older queer viewers. Izzy believes that in piracy as in intimacy, letting down your guard = getting killed. In a climactic scene of season one, as the freshly-dumped Blackbeard floats around in Stede Bonnet’s dressing gown, trying on a toothless, people-pleasing personality that isn’t his own, Izzy gives him an ultimatum: I take orders from Blackbeard, not whoever this new guy is.

Blackbeard realises he’s about to lose everything. He needs to assert his dominance, to give Izzy what he seems to want. Season one ends as Blackbeard creeps into Izzy’s room as the older man sleeps, severs his toe with scissors, and forces him to swallow it.

That was what took the show from interesting to great, for me – the yanking of the rug. All Izzy’s warnings about piracy being a dangerous profession turn out to be true. The scene is shot with sinister eroticism: Izzy is all but nude, Blackbeard crawling on top of him like a panther, clutching at Izzy’s heaving chest as blood dribbles down his chin, whispering the glassy-eyed promise, “Yes, Blackbeard, yes, yes.”

I love nightmare codependant horror partnerships. I write them often. As a second season was confirmed, I was so excited to see where they took this, with all their talk of healing and kindness, within that framework of romantic comedy where rowboats acts like a teleportation devices and seagulls can talk.

In the interim, I made beautiful friendships through the fandom. We bonded over how good it was to finally have a fun little show where we didn’t have to be braced for the old tropes, like bury-your-gays. We shared art, dressed up, and bawled together at karaoke bars. Those of us who were neurodivergent, older, kind of crunchy and bad at fitting in – we found friends through this character.

It was nice while it lasted.

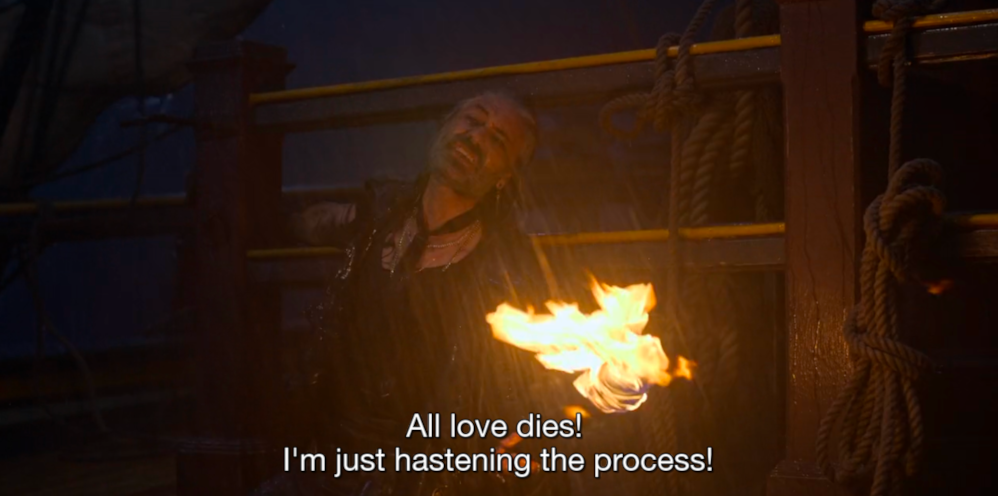

Season two finds Blackbeard in a dark place. “All love dies,” he says, showing off his new “trust no one” tattoo. In his heartbreak, he tortures his own crew, leads increasingly insane and violent raids, and snorts copious quantities of rhino horn, the show’s substitute for cocaine. His physical and emotional torment of Izzy ratchets up. He cuts off two more toes, and is about to take another when Izzy tells him he loves him. “I have love for you,” he says, like it’s a terminal disease. “I am worried about you, we all are.” This is the wrong thing to say. Blackbeard shoots Izzy in the knee and tells the crew to drown him. The crew, fond of Izzy, hide him and perform an emergency amputation on the infected limb.

“He is a dick,” says crewmate Jim, spattered in blood, “but he’s our dick.”

The tonal shift is stark. As plenty of other people have pointed out, it’s hard not to read these first few episodes as straightforward domestic violence. Izzy and Blackbeard are not a canon couple, but there is canon love there, on both sides, and season one worked hard to create narrative parallels between Izzy and Stede’s exasperated wife, Mary. And then there’s the theme song the showrunners chose for Izzy’s scenes…

Run from me, baby

Run, my good wife

You’d better run for your life

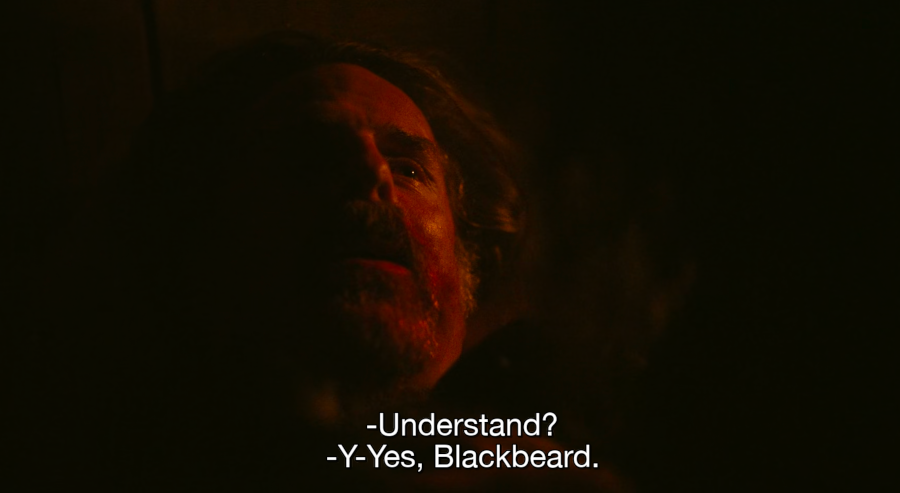

Inevitably, Blackbeard finds out Izzy is still alive, in hiding. To the desperate strings of Beethoven’s 7th, Blackbeard invites Izzy – pallid and half-delirious on his sickbed – to be the both the murder and suicide part of his own murder-suicide plan. Blackbeard knows he’s out of control and believes he needs putting down – in the parlance of the show, he needs “sending to Doggy Heaven”. He can’t go through with it himself, but he knows Izzy will always obey his orders, no matter how deranged. Izzy levels the pistol and bursts into hysterical laughter: “You scared, Eddie? Too scared to do it yourself? Clean up your own fucking mess, I’m not fucking doing it, I’ve been doing it my whole fucking life.”

The scene is beautiful, shot in sweaty chiaroscuro, and it’s extremely sexy, as all good melodrama should be. It’s also surprising for a comedy that opens with an extended fart joke.

And then Izzy shoots himself in the head.

At first, we only hear the gunshot. Later, we see the full act, uncensored, in close-up. Blackbeard hears the shot, keeps his expression neutral, and says what he never could before: “I loved you. Best I could.”

Blackbeard then calmly sets out to kill the entire crew and himself by sailing into a storm.

Still a romantic comedy, by the way. Talking seagulls and slapstick. But the Blackbeard/Izzy scenes are curiously detached from the rest of the show, a pocket of Hell in which two men who built a life together are apparently now building a death for one another too.

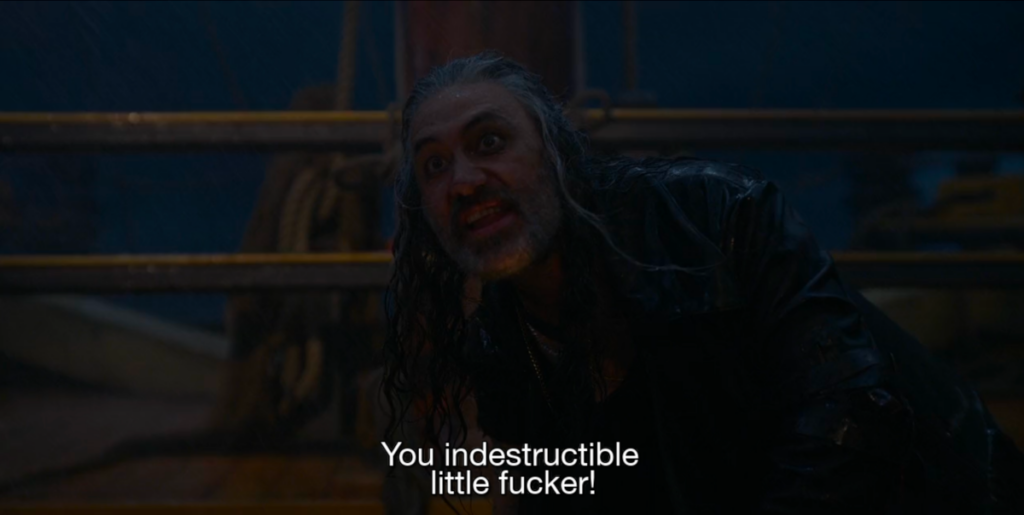

The storm throws the ship around like a toy. As it seems all hope is lost, it’s revealed that Izzy has survived. The bullet glances off his temple, leaving a long, burnt gouge. In the jaws of the hurricane, he hauls himself upstairs with one leg and a bleeding head wound, takes aim and clips Blackbeard in the arm so he can’t murder the crew. Blackbeard cries out with mad joy and disbelief, “You indestructible little fucker!”

It’s the highest of feverish romance. It’s true nautical melodrama. Genre be damned, I was so happy, so well fed. A brutally wounded man – a suicide survivor who wears the scar of his attempt on his face – saves the day. I thought about how hard it was to drag myself four feet from my hospital bed to the bathroom with my immense leg wounds after open heart surgery. I saw in Izzy that grit, that dogged determination to keep going in the depths of pain and despair. When do we ever get anything so juicy? God, I thought, this is everything I wanted. I can’t believe they went there.

It’s one thing taking off. It’s another to stick the landing.

I want to talk about the facial wound for a second. This was a realistic point-blank gunshot as they appear when they glance off the bone. It’s a burn, a mess of gunpowder and blistered skin. Injuries in OFMD are generally treated with cartoon logic: being stabbed on the left side means nothing because no one has organs on their left. A cannonball to the head is… kind of fine? Poisoning is temporary. But stark realism is reserved for self-injury. Why?

This wound remains on Izzy’s face for the rest of the season. Drinking heavily, isolating himself while the rest of the crew have slapstick adventures, shouldering the blame with repeated assertions of “serves me right”, and, finally, the pitiful statement “when I told him I loved him, he shot me”. When his makeshift prosthetic leg humiliatingly breaks, Izzy crawls along the deck chanting “you’re born alone, you die alone”. It’s a gut-wrenching moment, absolute rock bottom, and arguably unnecessary considering what we’ve already seen this character go through. But it leads to something in tune with the show’s theme of kindness…

The crew band together to build Izzy a new prosthetic from the ship’s figurehead – a unicorn. As he gingerly accepts the gift and the fond note stuffed inside, Izzy sobs. “For the new unicorn,” says the note. Figureheads are the protective spirits of ships, works of art maintained at great cost and pride. Izzy now physically embodies the essence of the Revenge. He saved the crew’s lives, they save his dignity. It was beautiful. I was moved. I sat down and created a miniature of the prosthetic in silver so I – an indestructible little fucker – could wear it as a talisman. My difficult leg is the same side as Izzy’s. I felt included. Seen. Despite the surprising shift in tone, this was everything I loved about the silly little pirate show with the good intentions.

By mid-season, Izzy’s healing arc culminates in a gorgeous drag rendition of La Vie En Rose in which Izzy changes the French lyrics from “I live for him” to “I live for you”, the collective, the crew. He’s found a life outside of Blackbeard. He’s succeeded in leaving: he’s free, and Blackbeard is free too. They’re at peace with parting ways. In episode eight, the finale, Izzy proudly says “[piracy is] about belonging to something when the world has told you you’re nothing.” He’s still drinking hard, but he’s smiling, defiant – he’s loved and accepted.

Then they kill him.

“It’s a suicide mission,” Blackbeard says.

Stede smiles. “It’s only suicide if we die.”

Suicide. There was only one suicide in the show: Izzy’s. And he’s the only one who dies in the mission. This cruel irony is never once addressed.

It’s his disability that gets him killed, crucially. Izzy’s new golden unicorn leg is visible for the Navy to see as he attempts to escape from prison in disguise. In a moment so brief it could almost be an accident, Prince Ricky, the man to whom he delivered the speech about belonging, shoots him in the left side. The side that canonically means he’ll survive. Izzy struggles back to the Revenge, with very little help – he limps and is left behind for most of the fleeing scene. In Blackbeard’s arms, he states – with his suicide scar on his face – that it’s okay, he wants to go. He apologises to Blackbeard as he bleeds out, as if the man hasn’t brutalised him and the rest of the crew for months. “I fed your darkness,” he says, as if Blackbeard has no agency of his own. As if Izzy didn’t try to leave. As if they haven’t already come to terms with each other, and both escaped that pocket of Hell.

Nonsensically, they bury him on land. A legendary sailor. They bury him without his beloved prosthetic, using it instead as a grave marker. That hideous trope. Would you use a friend’s leg bone as a tombstone? No? Think about it.

The worst of it is that Izzy was right. All his fears about opening up to love turned out to be true. Intimacy and acceptance will indeed get you killed. Was that the show’s message all along? That all this community and healing is ultimately hollow, reserved only for the right kinds of people?

Where was kindness?

No one else in the show suffers as Izzy does, even characters who revel in torture, in empire, in careless hate. No one else opens up to intimacy and community as Izzy does. No one else in the Revenge crew is punished with death.

Run from me, baby

Run, my good wife

You’d better run for your life

There’s an eerie lack of weight to Izzy’s suffering and demise. The crew makes jokes around his grave. That’s that, they say. Nothing comes of his loss, no revelations, nothing he hadn’t already said or proved by his actions. The crew walks away. Blackbeard and Bonnet open a B&B on top of Izzy’s grave. It’s breathtakingly cruel. It’s also just… kind of crap.

Izzy’s death is a pointless one. It’s the erasure of the single cripple, and without a strong narrative setup – or indeed any discernible setup – for his death’s meaning, we’re left with the impression that he must die to let the abled characters go on without guilt or discomfort. His wounds are a reminder of Blackbeard’s unhinged past; they must be buried out of sight, because all Blackbeard himself manages is one mumbled “sorry” before literally running away.

Other OFMD characters suffer injury and use prosthetics, but only Izzy is disabled, left to reckon with his new place in the world and openly grieving it, reckoning with it, turning himself into something new after literally crawling and weeping in front of the abled characters. I cannot tell you how painful it was to watch his downfall as a disabled viewer. In a show about kindness, about escaping the cycle of abuse, reality is a rubber band until a disabled man ‘should’ die.

We were promised something different. What we got was a mixture of inspiration porn, bury-your-cripples, and out-of-the-closet-into-the-fire. Found family, but disabled people need not apply.

It was supposed to be kind.

I’ve grappled with this as someone who enjoys genre-blurring, who writes largely bittersweet endings. I enjoyed the clever rug-pulling moments of season one, and the melodrama of early season two, where we get to see the full horror of piracy, and a glimpse of where codependent relationships can lead. But we were promised, textually and in the press, a resolution where for once – just this once – the marginalised audience gets to win. Where mercy prevails.

Oh, it’s a genre issue. I eat dead doves for breakfast. The Terror is my comfort show. I almost exclusively write tragedy, but I know to telegraph it. Compassion is important. It was absent here.

Oh, pirates die. Blackbeard is literally bludgeoned with a cannonball and survives without issue.

Oh, it’s sour grapes. I can accept main character death. What I can’t accept is sloppy storytelling. Earn your agonies. To lay out a romantic comedy, give us an explicit tragedy, and treat exceedingly serious issues so carelessly… that’s just poor. That’s a skill issue.

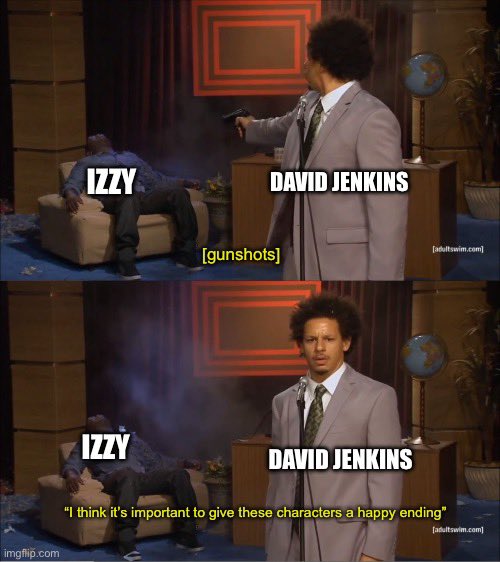

And then there’s the post-finale interviews with showrunner David Jenkins…

“[Izzy has] been through enough.” So he has to be shot like an injured horse? Canonically, Israel Hands was the sole survivor. Why the decision to subvert that, when the other pirates sail off into the sunset together?

“I think it’s important to give these characters a happy ending.” Um…

“He’s a father figure, and father figures have to die”. Then why did you spend 18 months giving interviews explicitly citing Izzy as a jilted spouse? The third part of a love triangle? Why the theme song “Run, my good wife”?

“Funerals bring families together.” Even if that were true, the funeral scene is devoid of emotion, and the idea of a disabled man’s death occurring to bring the group together is glaringly callous.

The fans are stunned and betrayed in a way I haven’t seen in fandom for years. I’ve collected a few comments out of thousands:

I don’t think any of this was calculated on the part of the writers. I think it was ignorance. And somehow, that’s worse. My use of the word ‘melodrama’ is deliberate. Melodrama theatre was always a place for marginalised audiences to safely express their emotions, to experience a space in which the oppressor is always held to account, where no pain is left unavenged. OFMD is a world in which homophobia does not exist, but sadly ableism is very much alive and unchecked.

It’s important to say here, the actor who plays Izzy – Con O’Neill – has always been a beloved figure in the fandom, fully aware of how important this character is to marginalised people. He did a beautiful job with the material he was given. As an older queer man who came out as a direct result of the show, we appreciate him and everything he’s done. He was only informed of his character’s death halfway through the season. It was a nonsensical waste of a great character and a brilliant actor.

Izzy Hands remains our Indestructible Little Fucker. We loved this brief taste of a flawed man, a product of abuse and repression, who was accepted into the fold along with his foul-mouthed spikiness and taken on as the protective spirit of the ship, embodying the show’s professed values. He’s always going to have a devoted fanbase. He’s a dick, but he’s our dick.

There’s a lot wrong with season two aside from Izzy’s storyline. The polyamorous couples are broken up for no apparent reason, the pacing is uncomfortably fast, and the main couple are stripped of any chemistry or emotional development. The show’s previous strong sense of message is gone. Emotional beats and plot threads are routinely disregarded. It’s a baffling and frustrating dropping of the ball after such a strong first season.

And look, sure, it’s only fiction. You’re welcome to argue that it doesn’t matter. But remember in Black Sails when John Silver stomped an ableist to death with his prosthetic leg? Yeah. That’s how you do it.

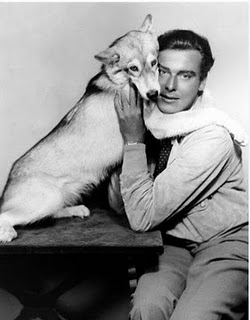

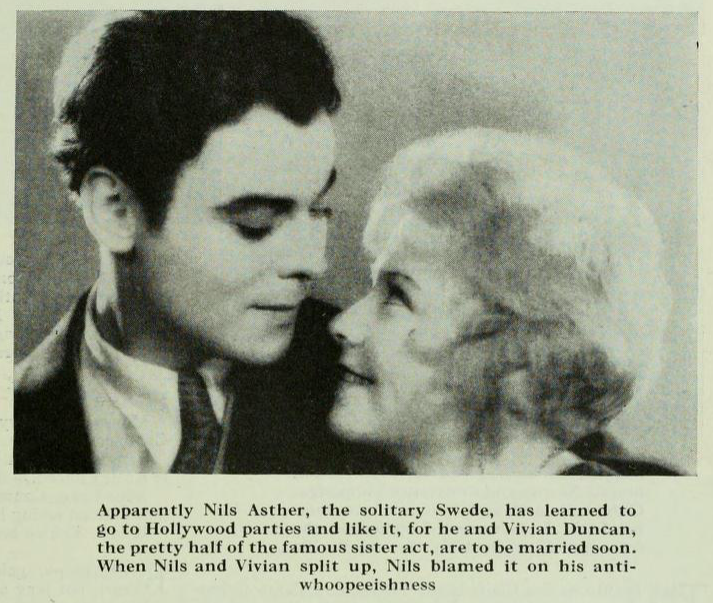

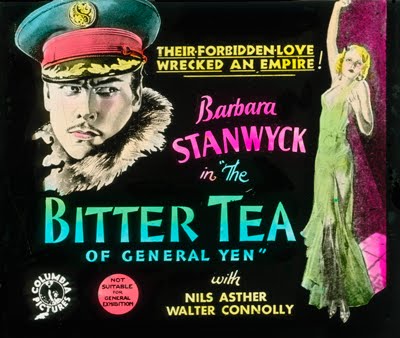

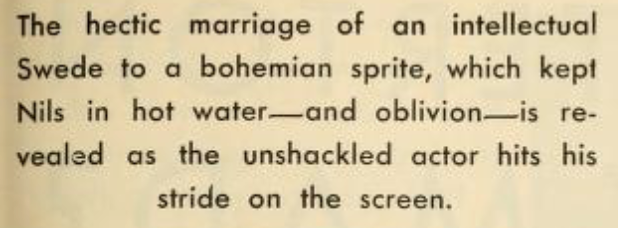

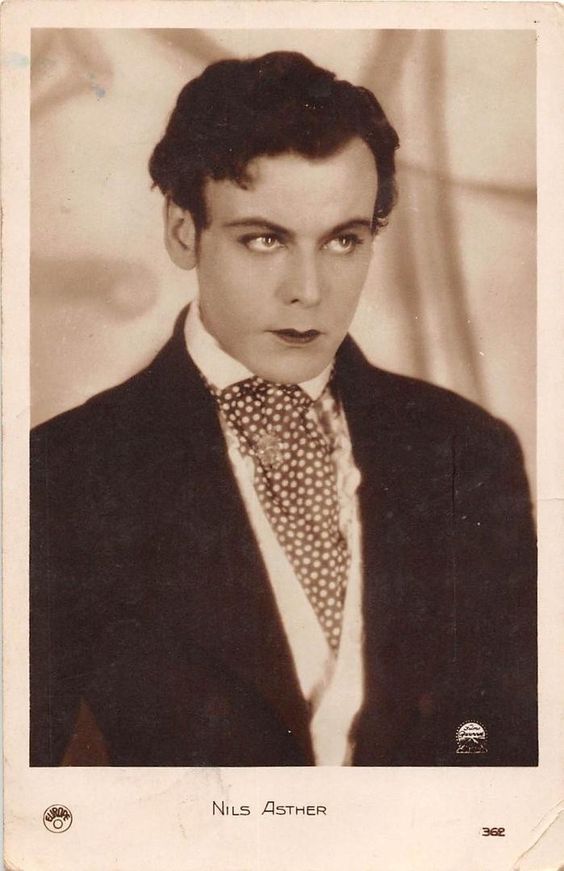

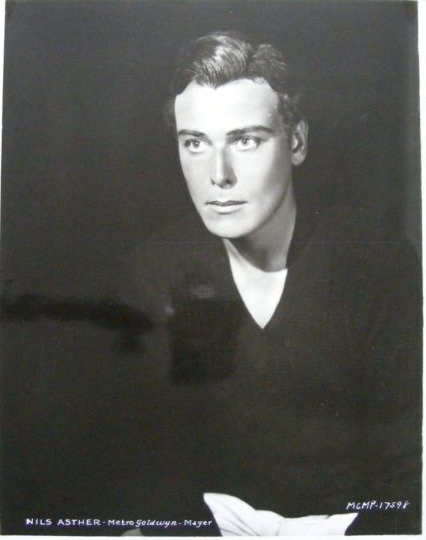

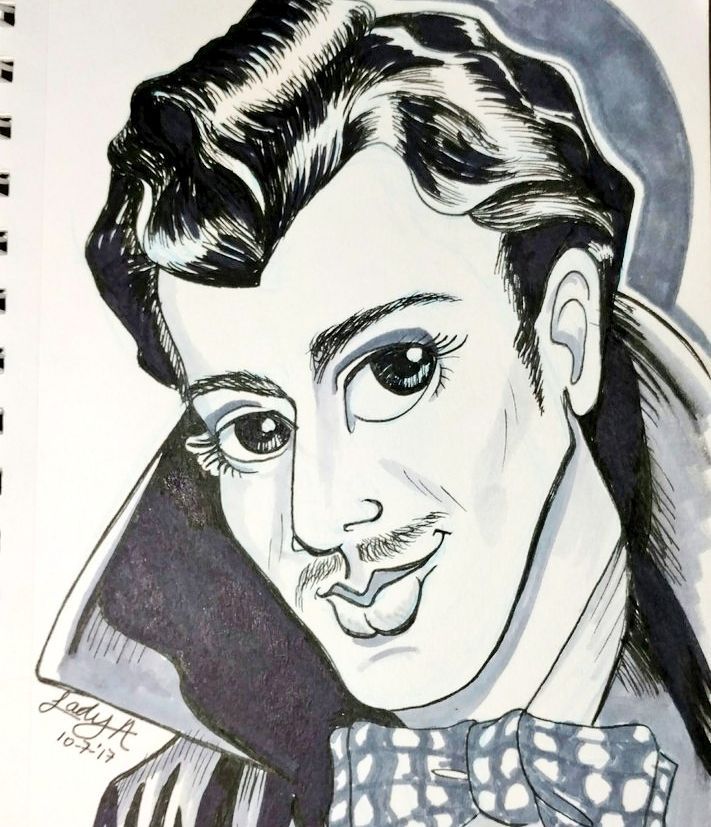

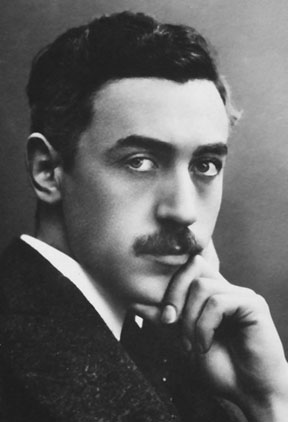

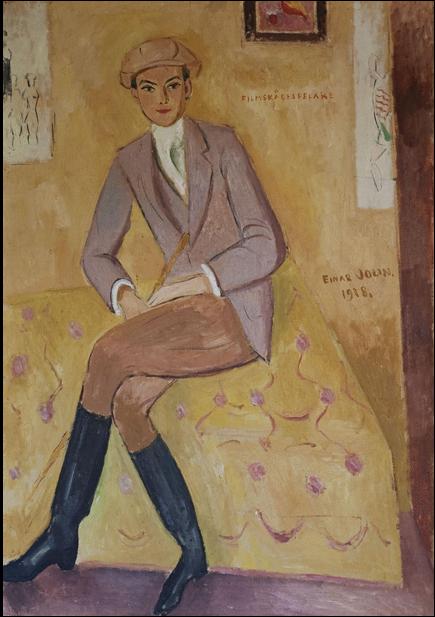

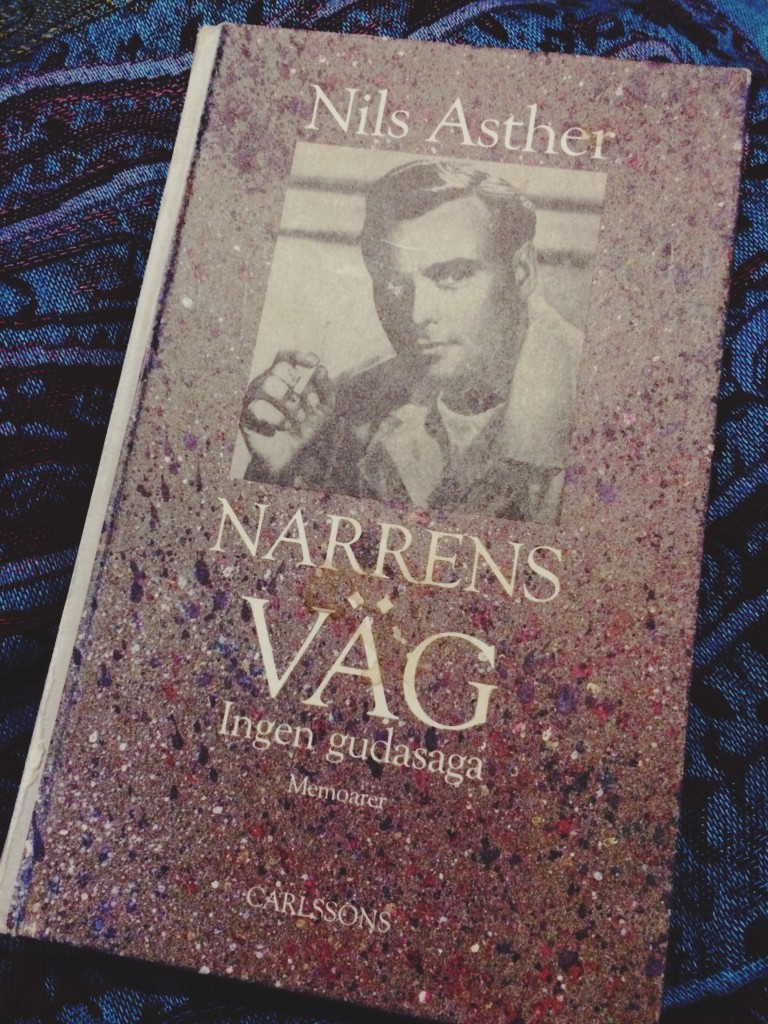

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

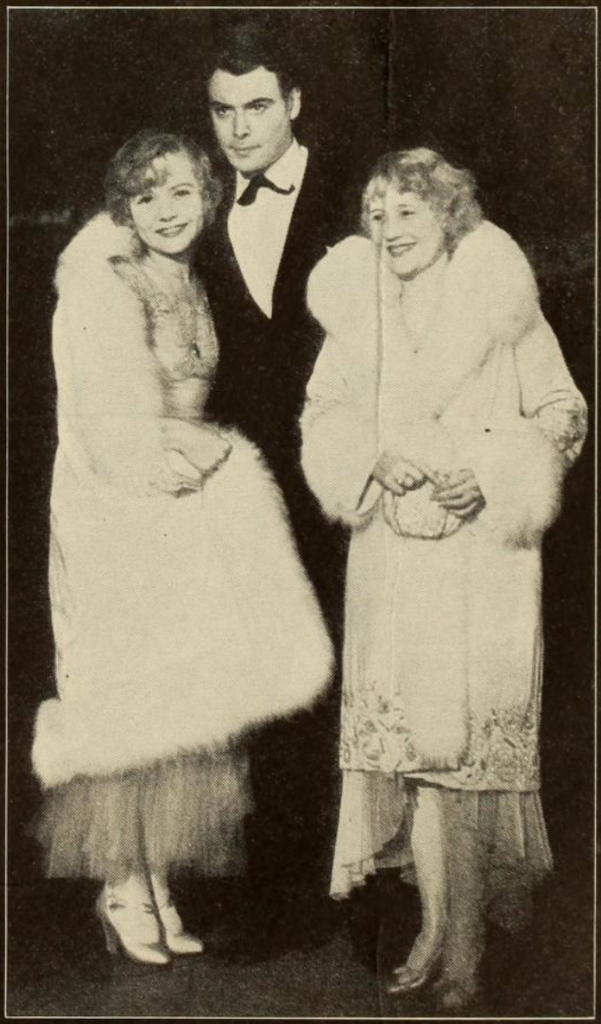

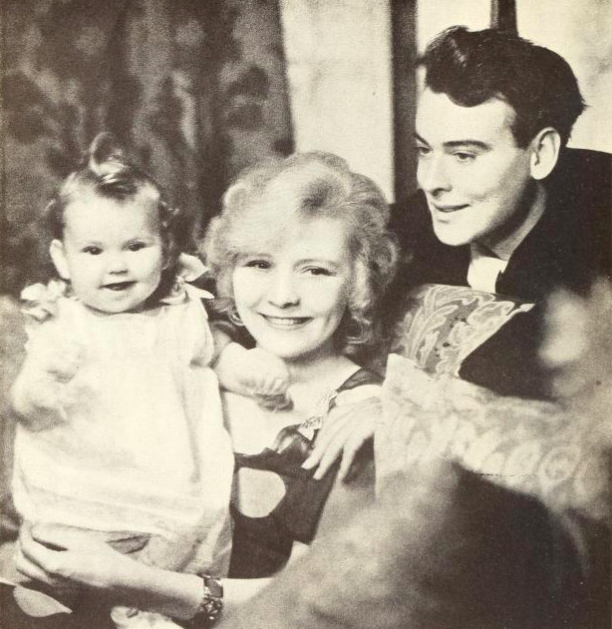

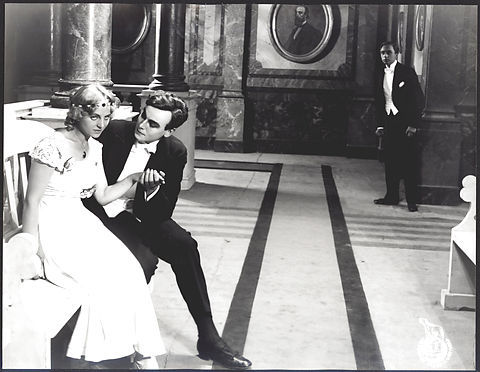

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.

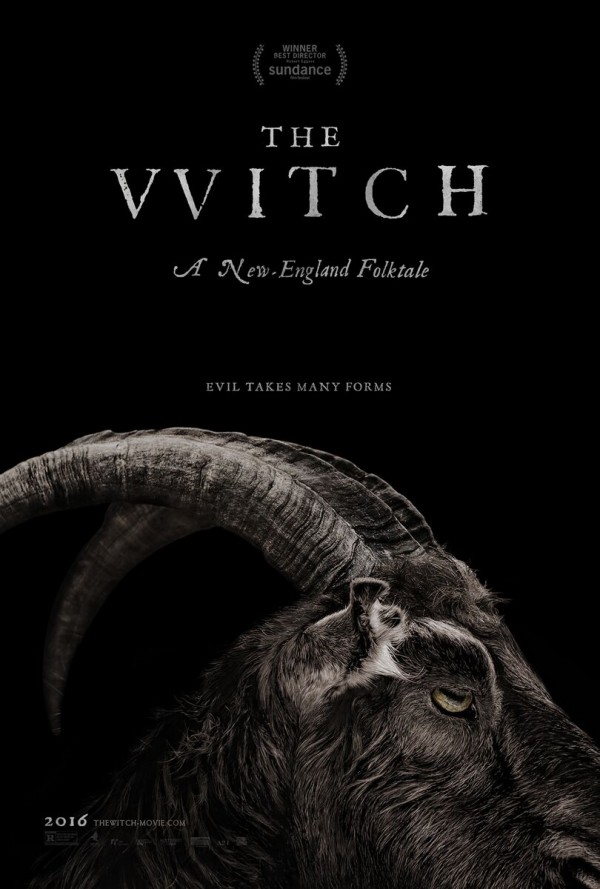

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of