I’ve been talking to author Helen Barrell about her new book Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science out now from Pen & Sword.

Professor Taylor appears in your last book, Poison Panic, to deal with some murderous Essex wives. How did he capture your imagination sufficiently to make you devote a whole book to him?

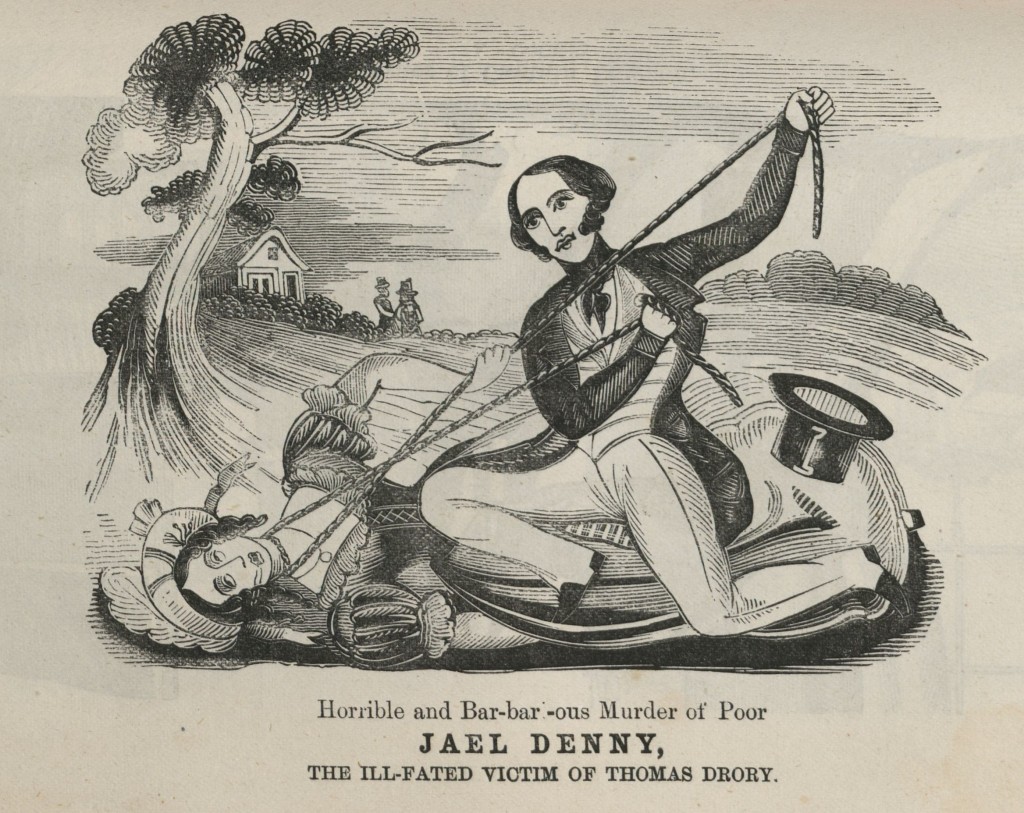

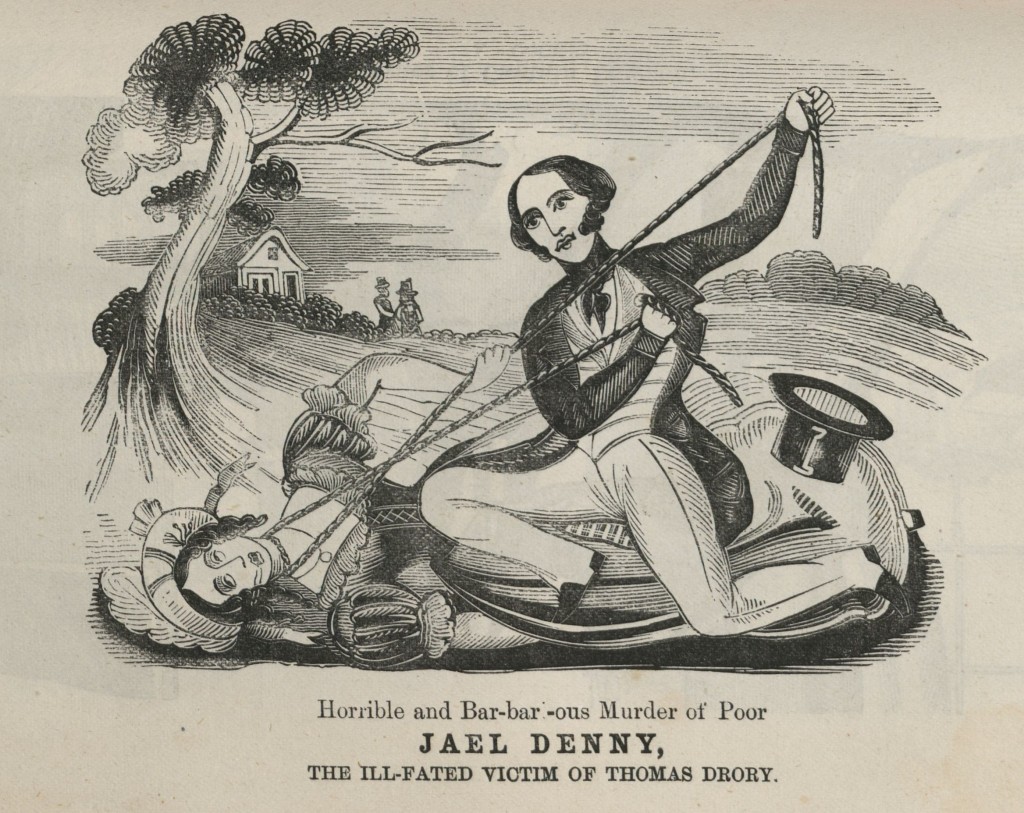

Taylor was the expert witness in the 1840s arsenic poisoning cases which involved Sarah Chesham, Mary May and Hannah Southgate. He was called in to work on all of the cases, and the papers were calling him “the eminent professor”, so I wondered – who on earth is this man? Then when I discovered he’d been summoned by the police to analyse bloodstains during the investigation of Thomas Drory, the Doddinghurst murderer,– and that’s as early as 1850 – I was surprised and intrigued.

I quickly found out that he’d been involved in a huge number of cases, and not always as a toxicologist, although that’s how he’s best remembered. Coupled with this was his massive output of books and journal articles, and his own editorship of the London Medical Gazette. His personality comes out in everything he writes; he’ll start in scholarly tone, but he just cannot resist injecting something of himself. It might be an unscholarly expression of amazement, it might be a sarcastic aside at an enemy, it might be a jibe at how stupid some criminals can be.

So not only are there fascinating cases involving a vast cast of Victorians, you’ve got a clever, sarcastic professor and the evolution of a science. Writing Taylor’s biography was utterly irresistible.

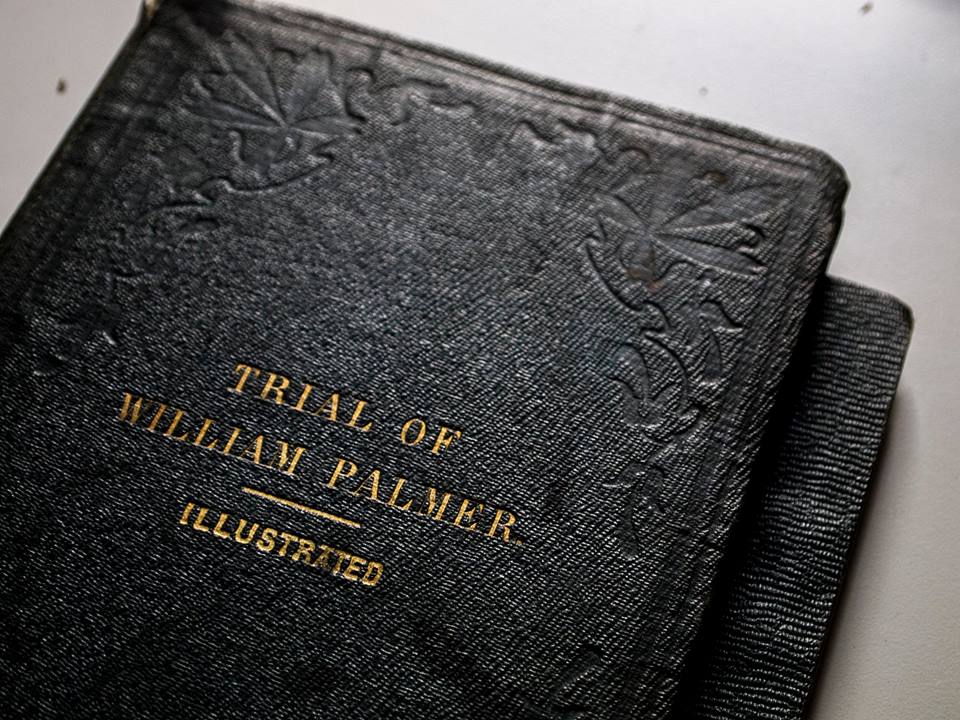

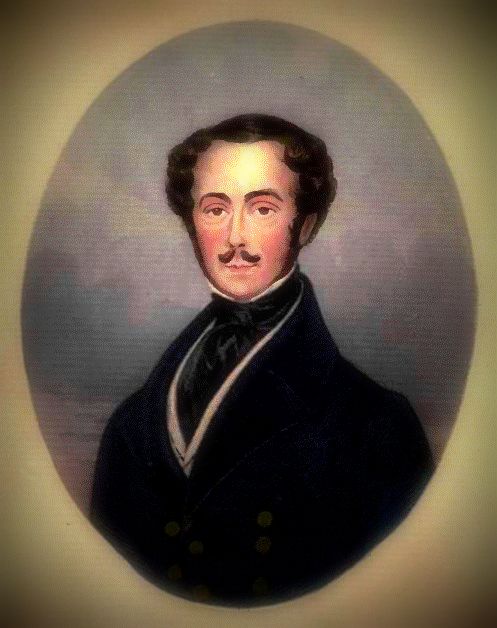

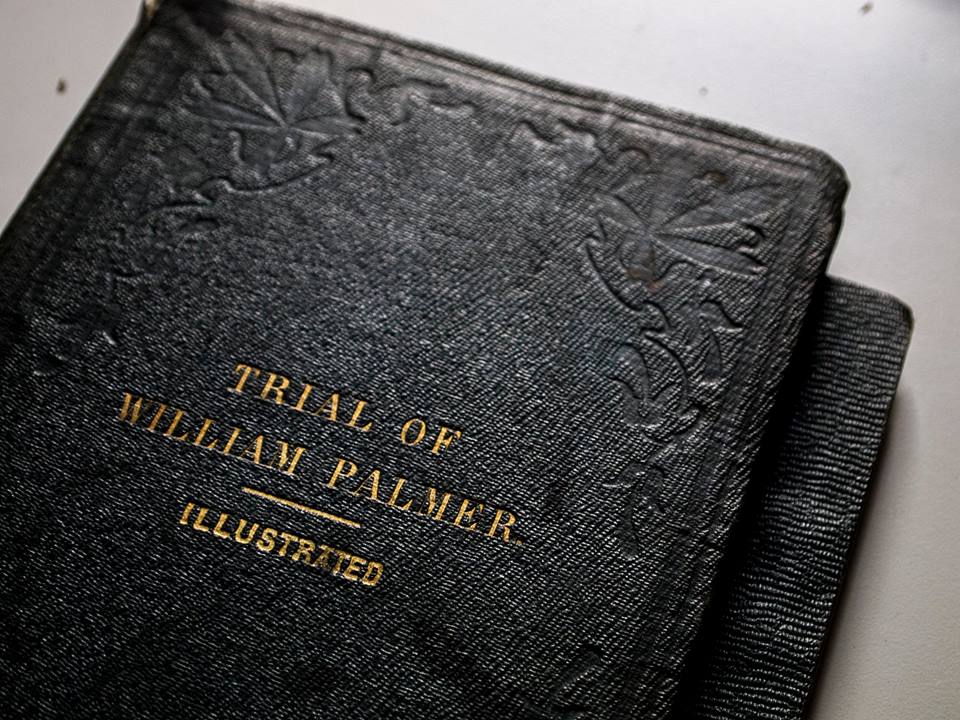

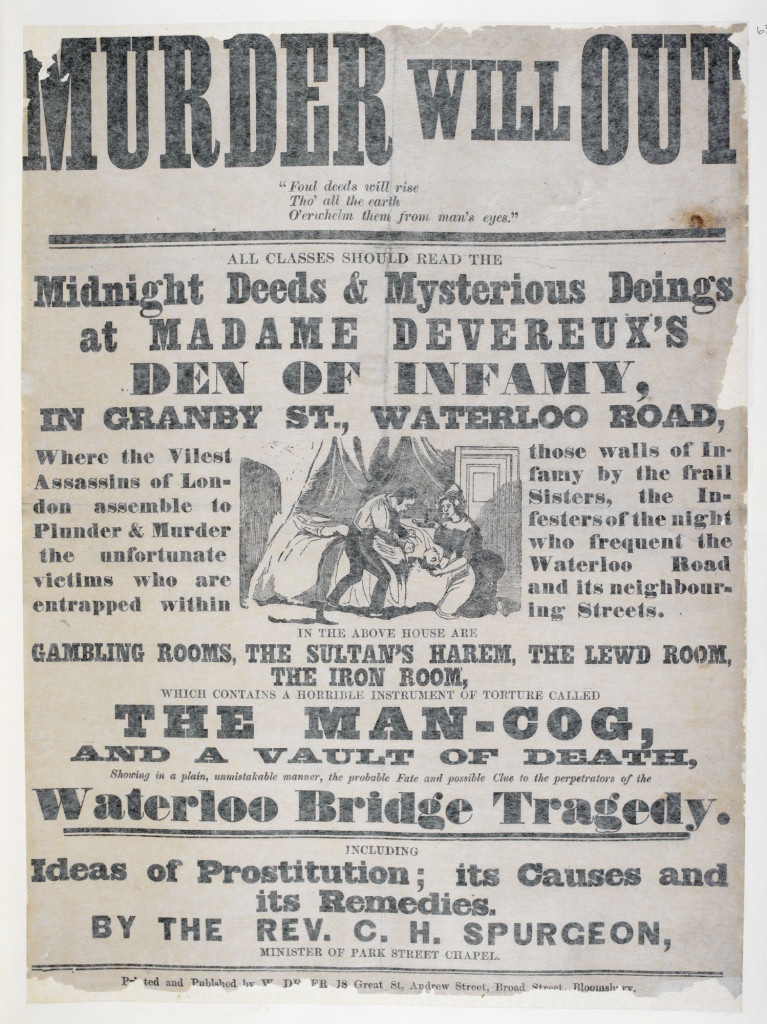

Victorian true crime enthusiasts will probably know Professor Taylor from the particularly nasty Rugeley Poisoner case. William Palmer, or ‘The Prince of Poisoners’, was a surgeon, and went to the gallows for his crimes. But that wasn’t the only time Taylor took down a fellow medical man for murder…

The Palmer and Smethurst trials are the only ones which Taylor worked on to be included in the famous red-bound volumes of the Notable British Trials Series. This is perhaps why Taylor is remembered almost exclusively for them, which means that nowadays his career is seen through a Palmer/Smethurst-tinged prism. But they were difficult cases, and Taylor himself harped on about them for years afterwards.

I have to say that researching and writing the 1856 Palmer cases gave me nightmares! I don’t live far from Rugeley, so my partner and I popped over on the train. We saw the pub where John Parsons Cook died, and I even went into the pet shop which occupies half of what was once Palmer’s house (I bought cat treats for my furry chums at home!). We saw the house where Palmer was born, and went to the church where Cook is buried and saw his grave. The stone was paid for by the priest who was the vicar at the time because so many people were visiting Rugeley purely thanks to the notorious Palmer, and along one side, almost buried now by grass and rising soil, is a line from Proverbs:

Enter not into the path of the wicked. Avoid it, pass not by it, turn from it, and pass away.

That night, I had a terrifying nightmare. I was in the churchyard at Rugeley in the twilight, and there was a horrible sense of evil in the air. I heard someone chant, over and over again, a line from the Lord’s Prayer: Deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil….

I managed to develop anaemia at the time, too, and so it felt like William Palmer was trying to finish me off as well! But it has to be said – when you’re writing about crime, real people died sometimes horrible deaths, by “unfair means”, as the Victorians used to phrase it. Although I found the Palmer chapter emotionally hard, I was relieved in a way because it meant that I hadn’t become desensitised.

But to move on to the other medical man who Taylor found himself toe-to-toe with, that would be Dr Thomas Smethurst.

These days, the jury is very much out on the 1859 Smethurst case, as some people think that Isabella, his “wife” whom he was accused of murdering, could have died from Crohn’s disease, or a similar intestinal complaint, aggravated by pregnancy. It was thought at the time that Smethurst used his medical knowledge to bump Isabella off.

Smethurst had originally married a woman who was 22-years his senior. While she was still living, he and Isabella Bankes, an heiress with an annuity, were carrying on with each other in the genteel lodging house where Smethurst was living with his first wife. Isabella was asked to leave by the landlady, and Smethurst quickly followed her. They were bigamously married, and not long afterwards, Isabella fell ill.

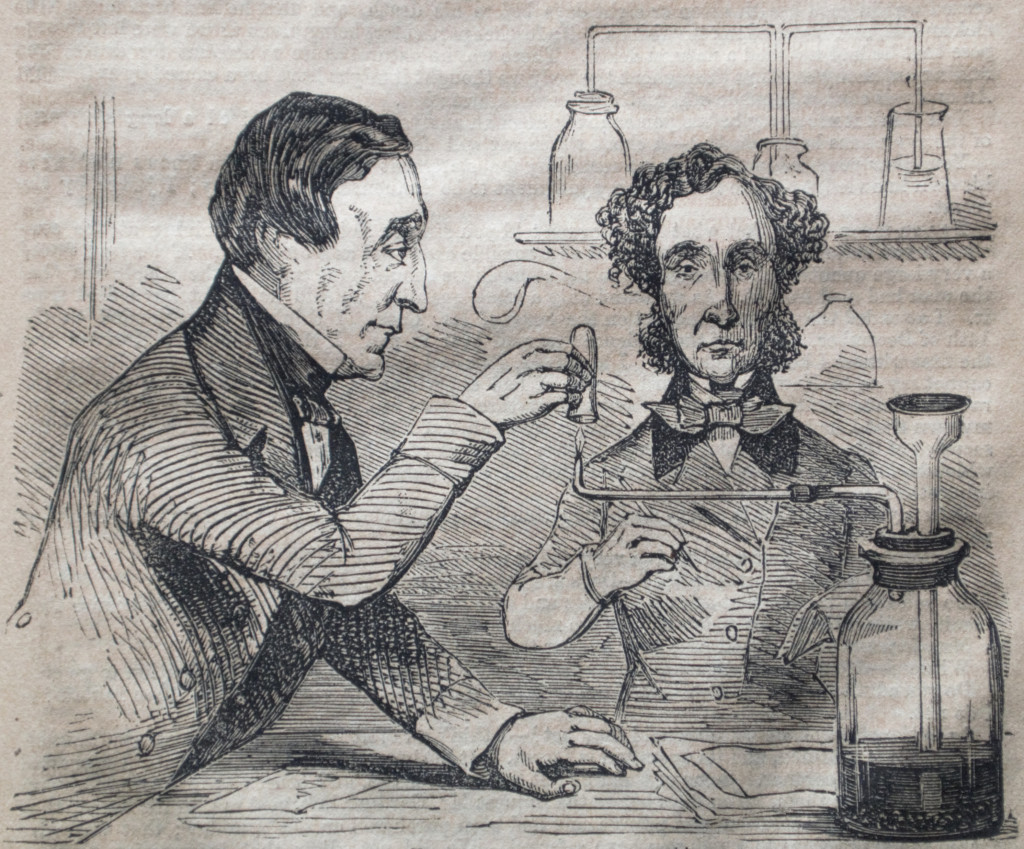

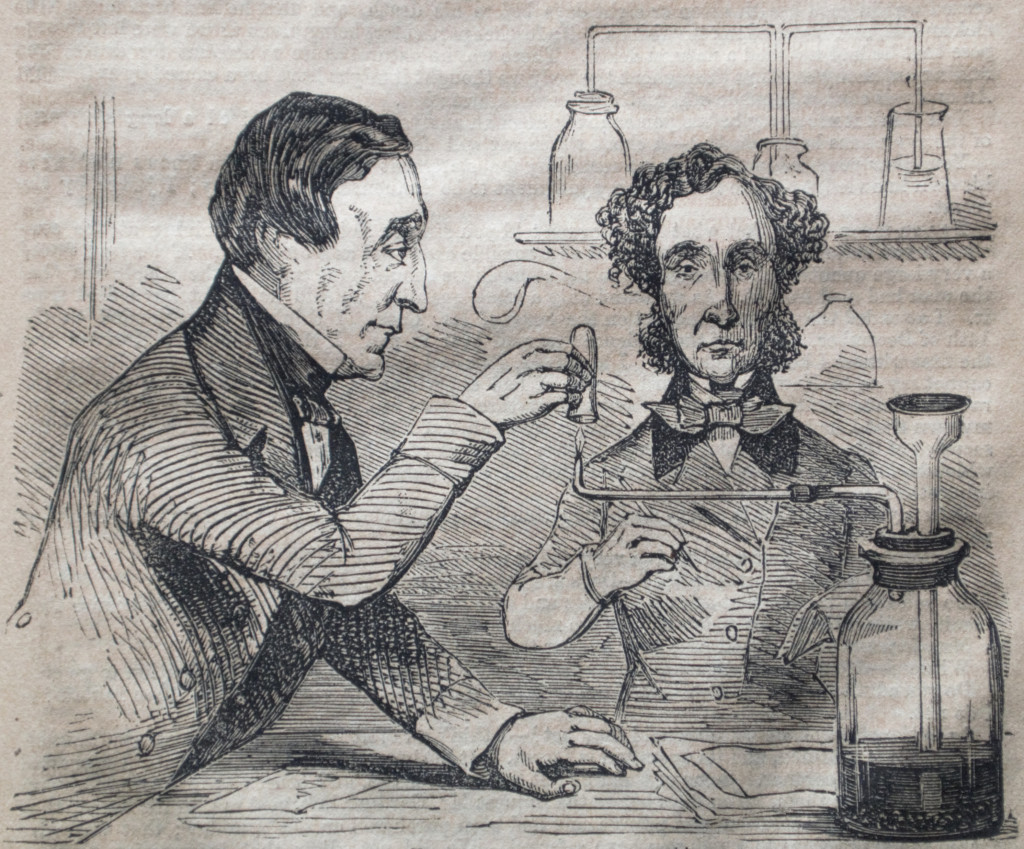

She had several doctors, besides her husband, caring for her, and all of them thought that something was off. One Sunday, Taylor was visited at home by a doctor bearing Isabella’s stool samples. Taylor lived in a on well-to-do Regent’s Park – one wonders what his neighbours made of the police and medical men who would drop by with articles for him to examine. On analysing one of the samples, Taylor found arsenic, and declared that Isabella was, quite likely, being poisoned, so her “husband” was arrested. Soon afterwards, she died.

Smethurst was a quack. He had a large collection of homeopathic remedies, and he had run a hydrotherapy spa in Surrey, which Dr Lane bought from him – in case that sounds familiar, Dr Lane was embroiled in the scandalous divorce case of Mrs Robinson. It’s very clear from his time as editor of the London Medical Gazette that Taylor had zero patience with quackery, and he had to examine all the homeopathy bottles looking for arsenic, and also antimony, which he found in Isabella’s body. Antimony wasn’t unusual in medicines, and arsenic was found in some as a pick-me-up – the risk was that Isabella could have been poisoned by one of the many remedies that Smethurst had in his possession. Or indeed, that so many bottles were an excellent way to hide the source of the arsenic, if Smethurst hadn’t already jettisoned it.

One of the bottles was mysterious to Taylor. It was almost empty and he only just managed to perform his favourite arsenic test – the Reinsch test – on it. It tested positive for arsenic, and he said that this was the likely source. Unfortunately, just before the trial, Taylor realised that he had made an error. The arsenic had in fact come from the copper which was part of the Reinsch test, and the mystery bottle had contained a chlorate which dissolves that metal. The arsenic in the copper gauze was released because the chlorate had dissolved it.

Taylor owned up to this error, and tried to turn it to his own ends as a scientific discovery. Well, every cloud has a silver lining, I suppose. The jury still found Smethurst guilty of murder, but he mounted an appeal. Newspapers groaned under the weight of people who had an opinion on the trial – it wasn’t only Taylor’s problem with the copper that some quarters of the public found fault with. Wilkie Collins lampoons this in his 1864 novel Armadale, concerning the trial of Lydia Gwilt, who was:

‘tried all over again, before an amateur court of justice, in the columns of the newspapers. All the people who had no personal experience whatever on the subject seized their pens, and rushed (by kind permission of the editor) into print. Doctors who had not attended the sick man, and who had not been present at the examination of the body, declared by dozens that he had died a natural death. Barristers without business, who had not heard the evidence, attacked the jury who had heard it, and judged the judge, who had sat on the bench before some of them were born.’

Smethurst’s sentence was overturned. However, he was tried for bigamy and sent to prison anyway.

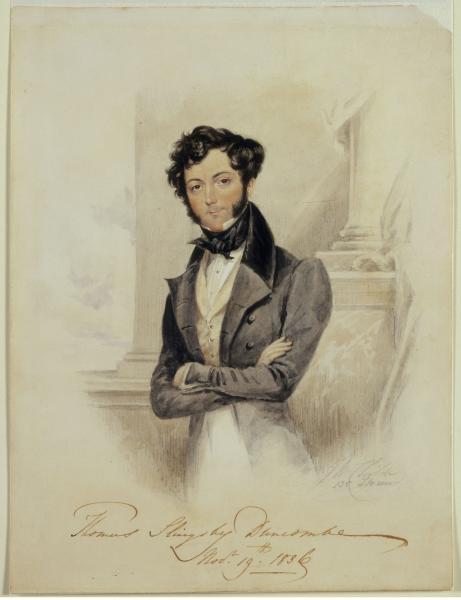

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Professor Taylor had some fantastic interactions with the luminaries of the day. Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins were fans, but Sir Arthur Conan Doyle went so far as to base a character on him?

I was very excited when I found a list of all the books in Wilkie Collins’ library (I’m a librarian, so this thrill should not come as a surprise) and was pleased to see that Collins had owned not one, but two editions of Taylor’s On Poisons. It’s safe to say that whenever you see any poison turn up in a Collins’ novel, he’s probably drawn on Taylor’s extensive research and compiled cases to inform his writing.

Charles Dickens was such a fan that Taylor gets mentioned several times in his magazines, and at one point Dickens even visited Taylor’s laboratory at Guy’s Hospital and was given a tour. Imagine Dickens, who seems so cosy now, gazing in amazement at flakes of human liver in a jar, and a stomach in a fume chamber.

And it’s entirely possible that Taylor is one of several men whom Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was thinking of when he created Sherlock Holmes. It’s well-known that Conan Doyle admitted to basing Holmes on one of his tutors at Edinburgh Medical School, Dr Joseph Bell, and he also said that Poe’s detective Dupin was an influence.

However, if you read Dr Watson’s first meeting of Holmes in A Study in Scarlet and you know about men like Robert Christison (another Edinburgh Medical School Man, and a near-contemporary of Taylor’s) and Taylor, then it seems like Conan Doyle is deliberately referencing them in the character of Holmes. Watson’s friend tells him that Holmes has been ‘beating the subjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick’ which is a clear reference to experiments Christison carried out during the trial of Burke and Hare in 1828. He talks about Holmes experimenting on himself and friends with poison, and Christison had written about how he and his scientific chums had put arsenic on their tongues to discover if it had a flavour.

When Watson first sees Holmes, he’s just that moment discovered ‘an infallible test for blood stains’. The famous amateur detective puts a plaster on his finger, where he had pricked it to draw his own blood, saying, ‘I have to be careful, for I dabble with poisons a good deal.’ Blood stain and poison analysis? This sounds rather a lot like Taylor.

And there’s also Taylor’s height, which was often commented on. His energy, and his biting sarcasm to anyone who had the temerity to disagree with him, all seem rather Holmesian. Conan Doyle mentions the Palmer trial in The Adventure of the Speckled Band, and refers to one of Taylor’s books in The Stark Munro Letters; Conan Doyle’s semi-autobiographical novel about a freshly qualified doctor trying to find his feet. Although Holmes might not use his test-tubes very often, they are often a feature in the background, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if this is partly Taylor’s influence.

Taylor almost knew of Conan Doyle. In 1879, the year before Taylor’s death, ‘ACD’ wrote a letter to the British Medical Journal about some self-experimentation with a flower used for curing headaches. Taylor was providing editorial for the BMJ at the time, and so he’s very likely to have read Conan Doyle’s letter. What he made of it we cannot, of course, now know.

And he had a bit of a reputation for… well, losing his temper.

The article Taylor wrote after the Palmer trial is extraordinary piece of work; the toxicological equivalent of a schoolboy thumbing his nose and chanting “neener-neener”. It drips with sarcastic rage; he carefully collated other cases and provided a chart showing aspects of strychnine poisoning, but the footnotes are full of exclamation marks, barbed comments and even sarcastic schoolboy Latin.

He loathed Henry Letheby and William Herapath – expert witnesses hired by the defence at the Palmer trial – and to be honest, they loathed him in return. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the animosity began, although it could have started off as professional jealousy – they were working in a new field and were trying to convince the public of the import of their work. After the 1845 Tawell trial, when a woman had been murdered after drinking stout laced with cyanide, there were irate letters in The Lancet between Letheby and Taylor – Letheby was most annoyed that Taylor, who hadn’t been one of the expert witness at the trial, had conducted his own experiments (could you smell cyanide’s distinctive almond scent when mixed with alcohol?) and written about it in an article on cyanide poisoning. He was really very rude about Taylor; although he didn’t name names, he stated that some people were writing about cyanide ‘to gratify the cacoethes scribendi’ (insatiable desire to write), which is clearly a jibe aimed at Taylor.

The sniping that went on between Taylor and the men who ruffled his feathers is hilarious – it’s just like today when you see academics arguing on Twitter. If Taylor was alive now, that’s exactly what he’d do all the time, I’m sure of it!

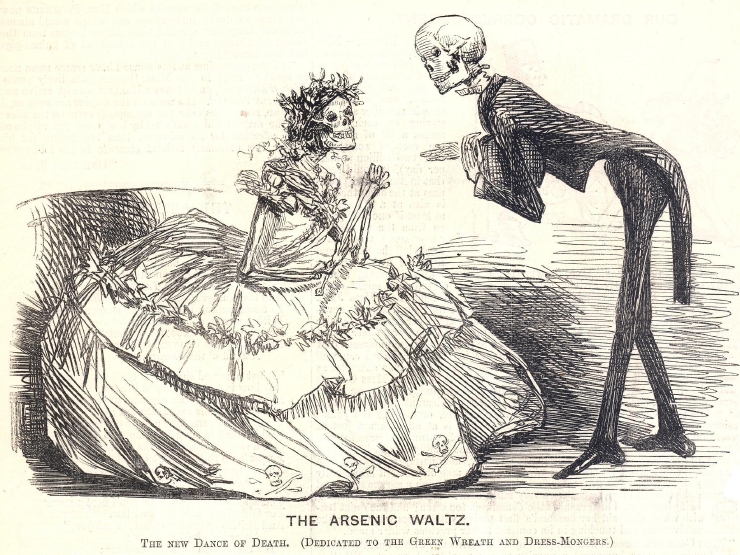

He would fly into a fury over public health matters too – he appears to be the first scientist to go public with the surprising idea that arsenical wallpaper dyes might just be a bit dangerous. He was roundly disbelieved, and arsenical dyes continued to be used in the face of mounting evidence from scientists.

I remember you telling me about having to gently explain saponification to your editor. You even have a section called ‘A Horror of Bad Smells’! Without ruining everyone’s dinner, what’s the single grossest thing you’ve come across in Professor Taylor’s career?

This is such a hard question to answer –there’s a heck of a lot of gross things in Fatal Evidence (I did try to avoid too many details though, but it’s possibly not a book to read over lunch), and it’s impossible to mention them without turning people’s stomach. Sorry chaps!

So move along, unless you would like him analysing tapeworms that he found in the intestines of an arsenic poisoning victim. Or would you like the theory one doctor had, that Mrs Wooler was being poisoned with arsenic up her bottom via enema syringe? How about his examination of people who had been dead for some while, whose bodies had turned to soap such that the individual organs were unrecognisable, and yet he was still tasked with analysing them? One of these saponified corpses took him a week to examine and he wrote a letter to the Coroner who had hired him, to complain of the terrible headache the analysis had given him – and the letter, which did not hold back on gory details, was deemed worthy of reproduction in the newspapers!

I imagine you yell at the TV when a Victorian detective squints at a corpse and whispers “Arsenic!”.

Let’s just say I had problems with Taboo and the twenty-minute arsenic test in 1815. In 1850, with the far more efficient Reinsch test, Taylor took half an hour at a trial to analyse a bag of white powder. Now – would it be at all plausible that several years earlier, with a less efficient test, someone was able to examine human organs for arsenic – in twenty minutes? I think not.

This is your second book, and a natural progression from Poison Panic. As a writer, what have you learned about the process from that first experience?

In terms of purely practical things, sort yourself out with a nice place to sit. I wrote Poison Panic on an ancient laptop at the dining table, and ended up hurting my shoulder because I was hunched over. As I knew Fatal Evidence would be a longer book, and would require lots of research, I treated myself to a desk and a PC. And I wrote Fatal Evidence on Scrivener – it made life a lot easier.

There was such a lot of research required for Fatal Evidence, so I used a couple of spreadsheets to keep track of it all. I’ve got a massive timeline showing all of the cases I could find in the British Newspaper Archive which involved Taylor, and ones that I spotted from other sources such as his books and articles – I didn’t use all of them in Fatal Evidence, and I’m certain there’s still cases that are out there somewhere which I wasn’t able to find. I felt very organised, although I’ve still got a massive storage box next to my desk filled with box files of research! I’m loathe to chuck it all out, but I’m not sure where to put it.

I have to say that while I was writing Poison Panic, I was beset with fear that I’d never actually finish it. I was almost frozen sometimes by Imposter syndrome, thinking that I was rubbish and incapable, and that surely someone somewhere had made a mistake because I just couldn’t do it. But I kept going. So when I came to write Fatal Evidence, whenever that feeling tried to raise its horrible head again, I could face it down by going, “I’ve finished one book, I’ll finish this one too!” I wasn’t panicking as much, which made the process less painful – anaemia and nightmares excepted!

And I can’t really finish without saying you’ve upped your costuming game from last time. Nice tailoring.

Thank you! The irony is that my professor outfit is technically cross-dressing, seeing as I’m dashing about as a Victorian chap, but it’s much closer to what I wear on a day-to-day basis than the Victorian lady’s costume I had for Poison Panic last year! I wear a Walker Slater tweed waistcoat with trousers to work, and when the weather’s cooler, I’ll wear my tailcoat too. That said, I don’t wear a cravat or Mr Darcy shirt to work – perhaps I should.

Thank you, Helen!

Fatal Evidence is a worthy successor to Poison Panic, and a must for true crime fanatics. Don’t forget to follow Helen on Facebook for regular updates on her research.

Braham, John, Esq.

Braham, John, Esq.

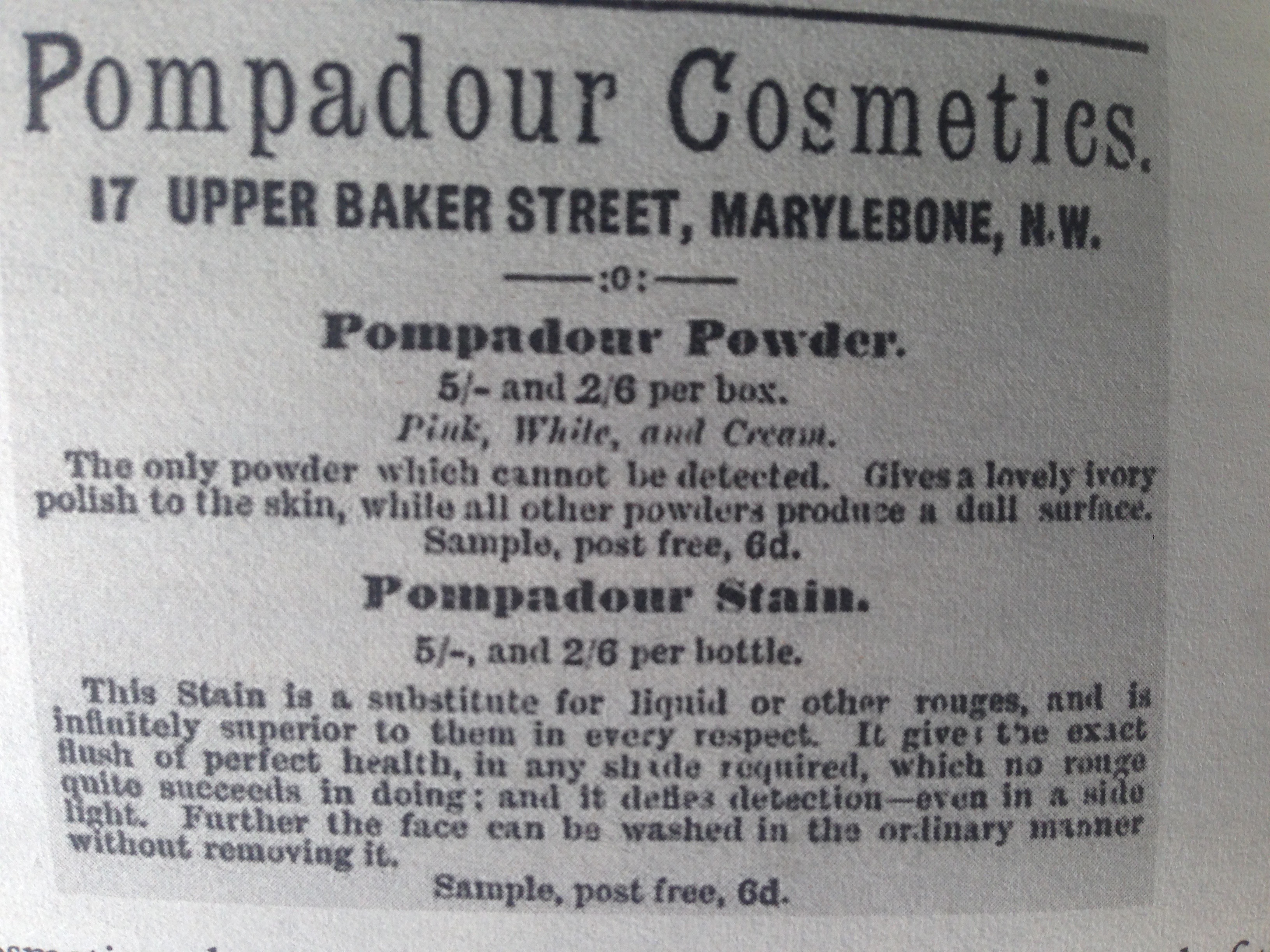

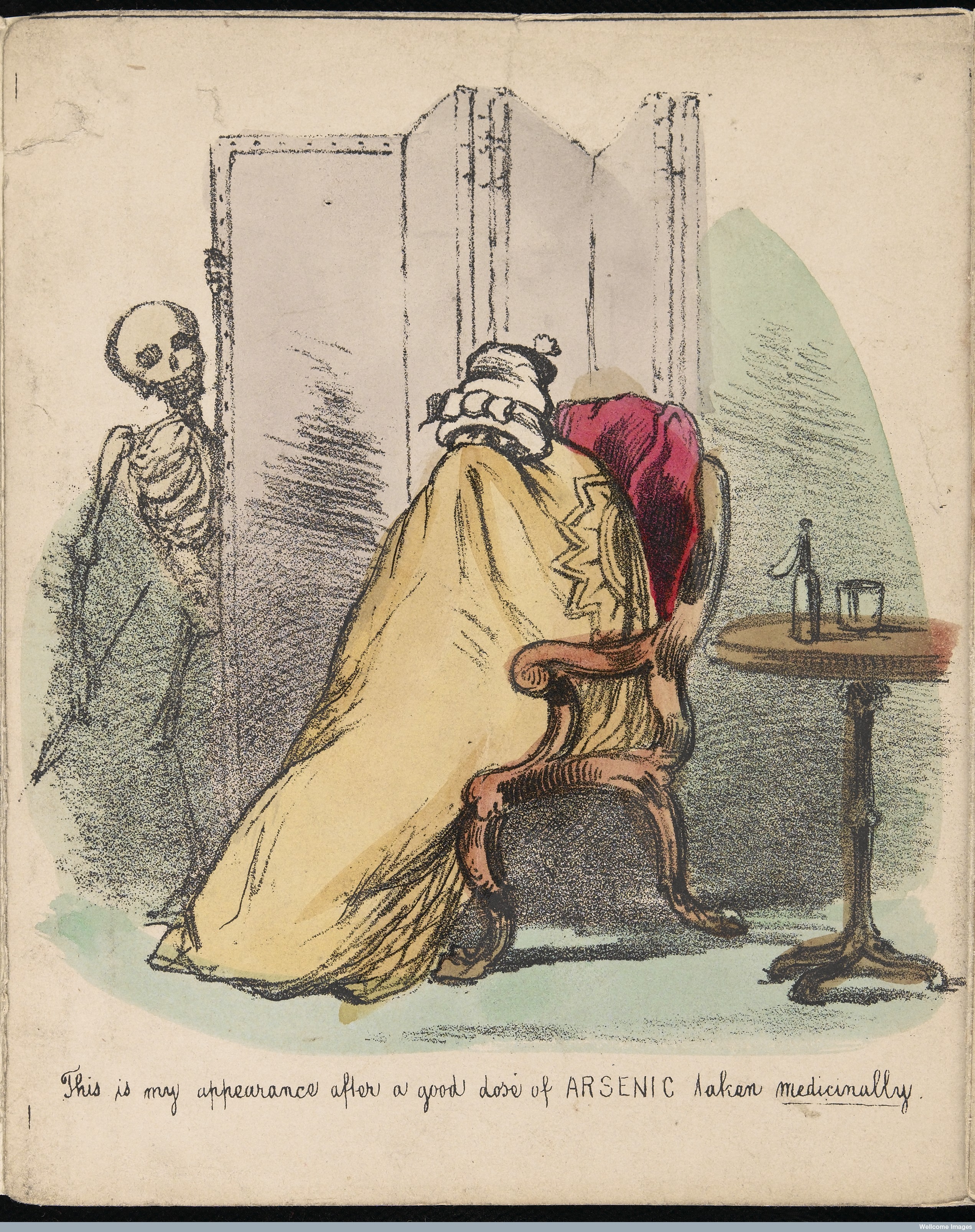

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

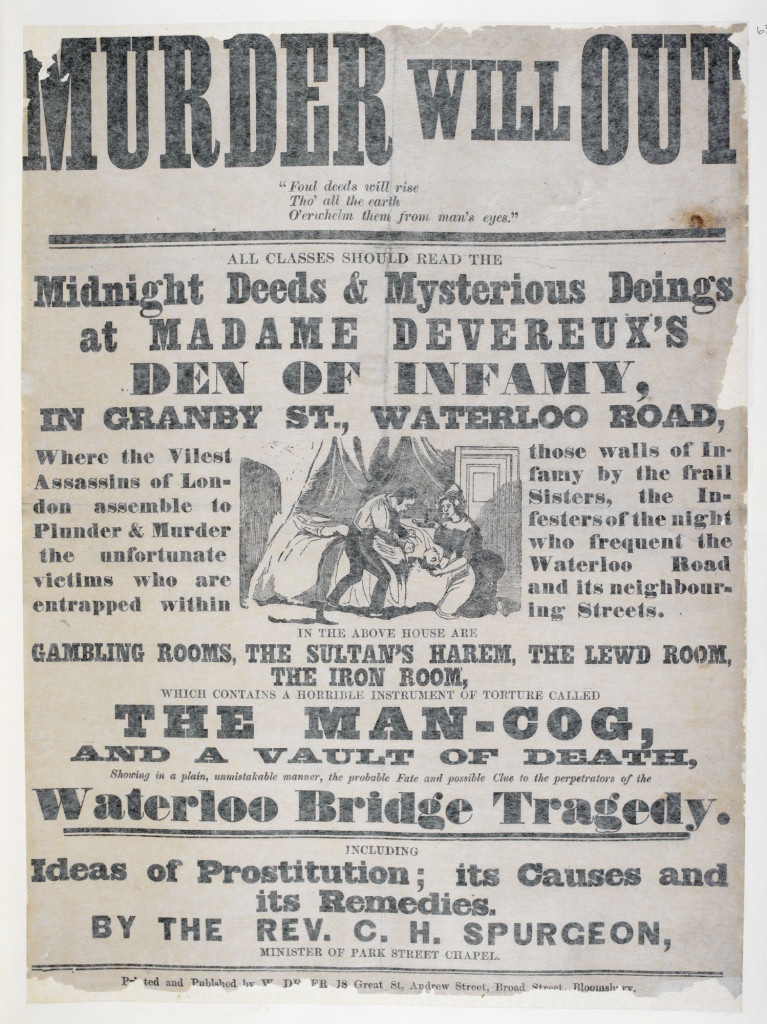

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments. At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.