Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale – The Blush

When I think of historical makeup, the usual image to spring to mind is a florid Rococo beauty smothered in powder and false hair. Victorian heroines had better things to do, like passing out on the moors and rejecting marriage proposals from clergymen.

Victorian women did wear makeup. It wasn’t proper to talk about wearing makeup, and it certainly wasn’t proper to look like you wore makeup. That was for actresses and other ladies of questionable virtue. Beauty, wrote nineteenth century agony aunts, came from clean living and inner purity.

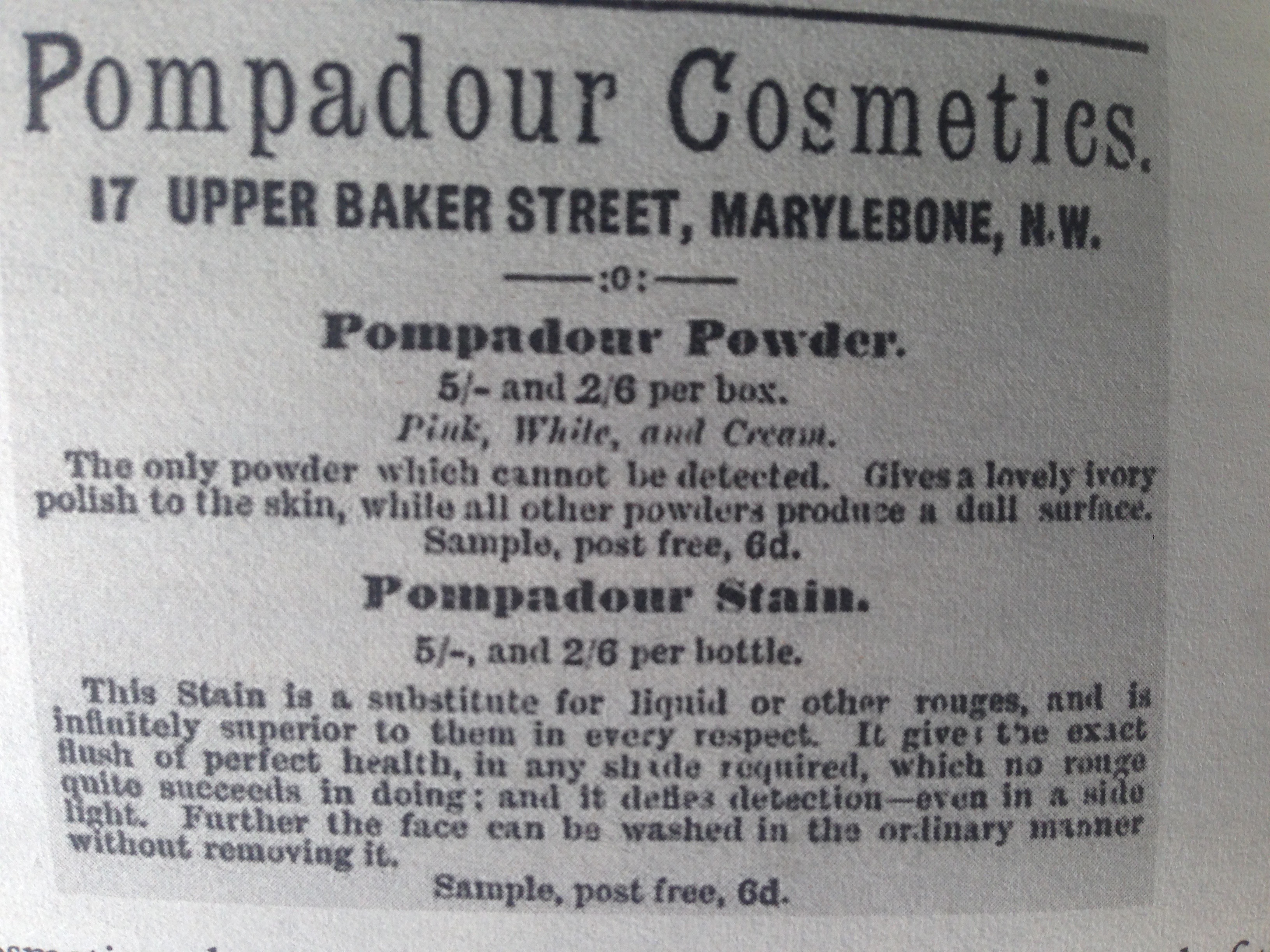

That’s rubbish, obviously. So women turned to cosmetics. As well as unwholesome, makeup was considered rather old-fashioned, carrying connotations of old maids cack-handedly tarting themselves up. The desirable look was that of the fictional milkmaid, who rose merrily at dawn with bright eyes, spent the day out in the fresh air (remaining untanned, importantly), and never read unsavoury novels. Her cheerful disposition gave her eyes sparkle and her cheeks a natural bloom.

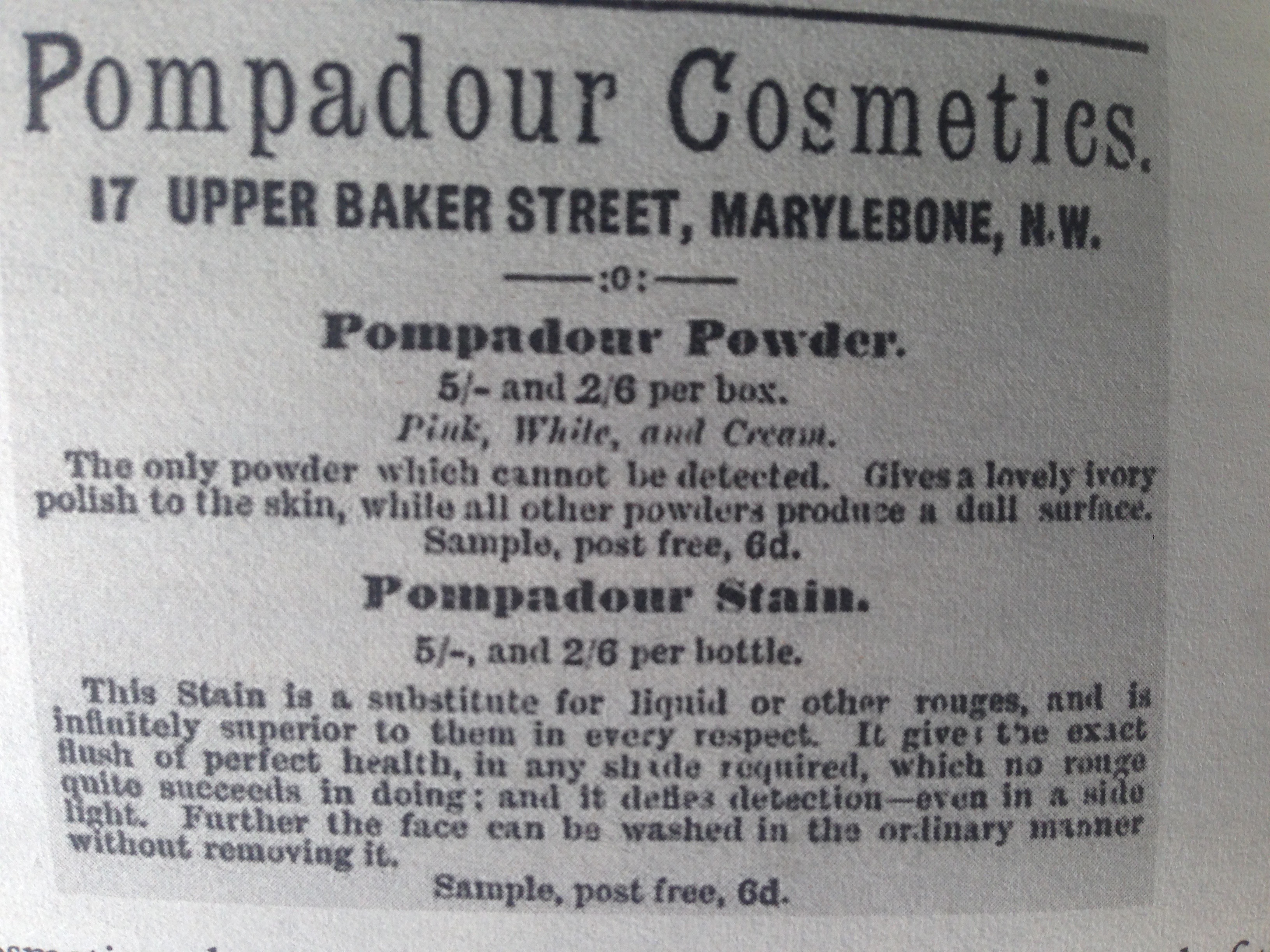

To achieve the milkbabe look, talcum powder, cold cream, and fragrances were normal and acceptable on any lady’s dressing table. They might be joined by eyebrow darkeners of coal or crushed cloves… and the dreaded rouge, so easy to apply too thickly.

Men, too, had their cosmetics. Mascara, or moustache wax, was applied with a fingertip to give definition to moustaches and eyebrows. Many Victorian women fell for the popular myth that regularly trimming one’s eyelashes would make them grow longer and fuller. It’s easy to see how such disasters would lead a woman to borrow from her husband’s mascara stash.

Men, too, had their cosmetics. Mascara, or moustache wax, was applied with a fingertip to give definition to moustaches and eyebrows. Many Victorian women fell for the popular myth that regularly trimming one’s eyelashes would make them grow longer and fuller. It’s easy to see how such disasters would lead a woman to borrow from her husband’s mascara stash.

Ruth Goodman’s How To Be A Victorian quotes one disapproving Victorian lady as saying rouge was “not only bad taste, but it is a positive breach of sincerity. It is bad taste because the means we have sought are contrary to the laws of nature.” With this quote in mind, it’s easy to see how Dante Gabriel Rossetti was accused of painting indecent women…

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Helen of Troy. 1863.

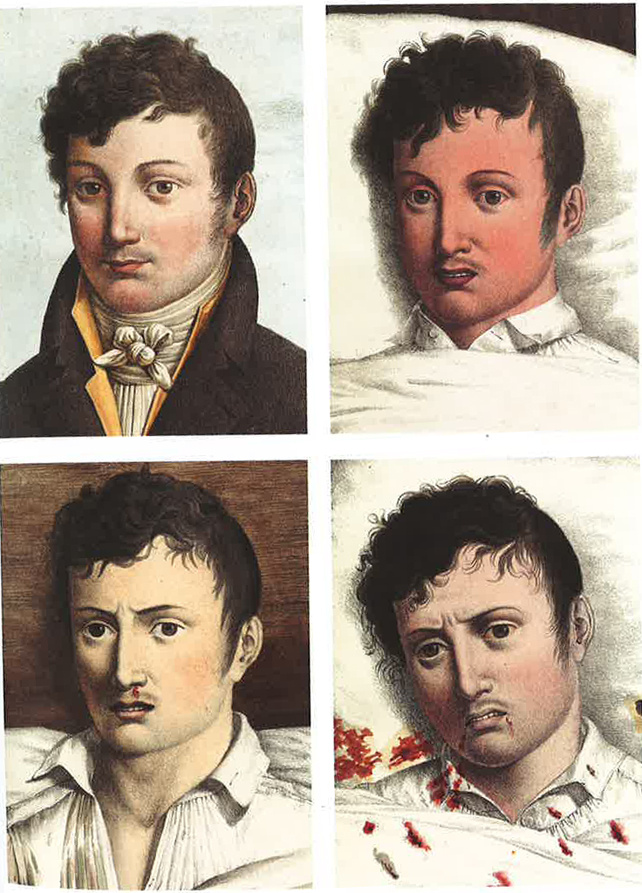

The vivid red lips typical of his later work give his models a savage, vampiric look, setting them apart from the dainty, delicately blushing ideal ladies of the day. They know they’re gorgeous, and they’ll probably bury you. Bear in mind, two dots of pink on a face as pale as that was a telltale sign of tuberculosis, too.

There’s a whole mountain of Victorian psycho-sexual neurosis when it comes to women’s faces and what they chose to put on them, which is partly why I was so excited when, trawling Etsy, I came across LBCC Historical Apothecary. There you’ll find authentic reproductions of cosmetics from all kinds of historical eras, from jazz age scented face powder to jasmine hair oil from 1772.

LBBC have plenty of rouges to choose from. I went for the Turkish variety. It’s a reproduction of an 1810 recipe that was used since at least 1740 and later on, too. It takes five months to make from repurposed violin shavings, and was said to be “beautiful and inoffensive”. In the bottle, it’s almost indistinguishable from blood, and smells like tasty floral vinegar.

So here I am, pretending to be a Victorian pretending to be makeup-free.

So here I am, pretending to be a Victorian pretending to be makeup-free.

On the lips, the rouge is a tad drying, but the colour lasts all day and sits happily under a layer of Vaseline. It doesn’t bleed. The only other lip tints I’ve tried are from Bourjois and Benefit, and both of them stain a heavy colour at first and fade quickly. This rouge acted differently from the start – I definitely prefer it to modern tints. It’s easy to imagine a Victorian woman using this clandestinely while her mother-in-law bleated on about ‘paint’.

On the cheeks, I stippled on a tiny amount with a soft sponge and blended it quickly before it had a chance to stain. Despite having no prior experience with any blusher whatsoever (pasty goth for life) I managed not to make any disasters, but I would say go easy. You can always add more.

Several hours and only one touch-up later…

That really dark bit’s a shadow. But now I want to try a more lurid eighteenth century look at a later date. And definitely the 1772 rose tinted lip balm for when I’m out and about, beheading nobles, etc.

That really dark bit’s a shadow. But now I want to try a more lurid eighteenth century look at a later date. And definitely the 1772 rose tinted lip balm for when I’m out and about, beheading nobles, etc.

“I love it all,” he would say, again and again. “The theatre of life.”

“I love it all,” he would say, again and again. “The theatre of life.”

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–