“I am inclined to think that sort of thing is mostly rubbish” – William Morris, on his own work.

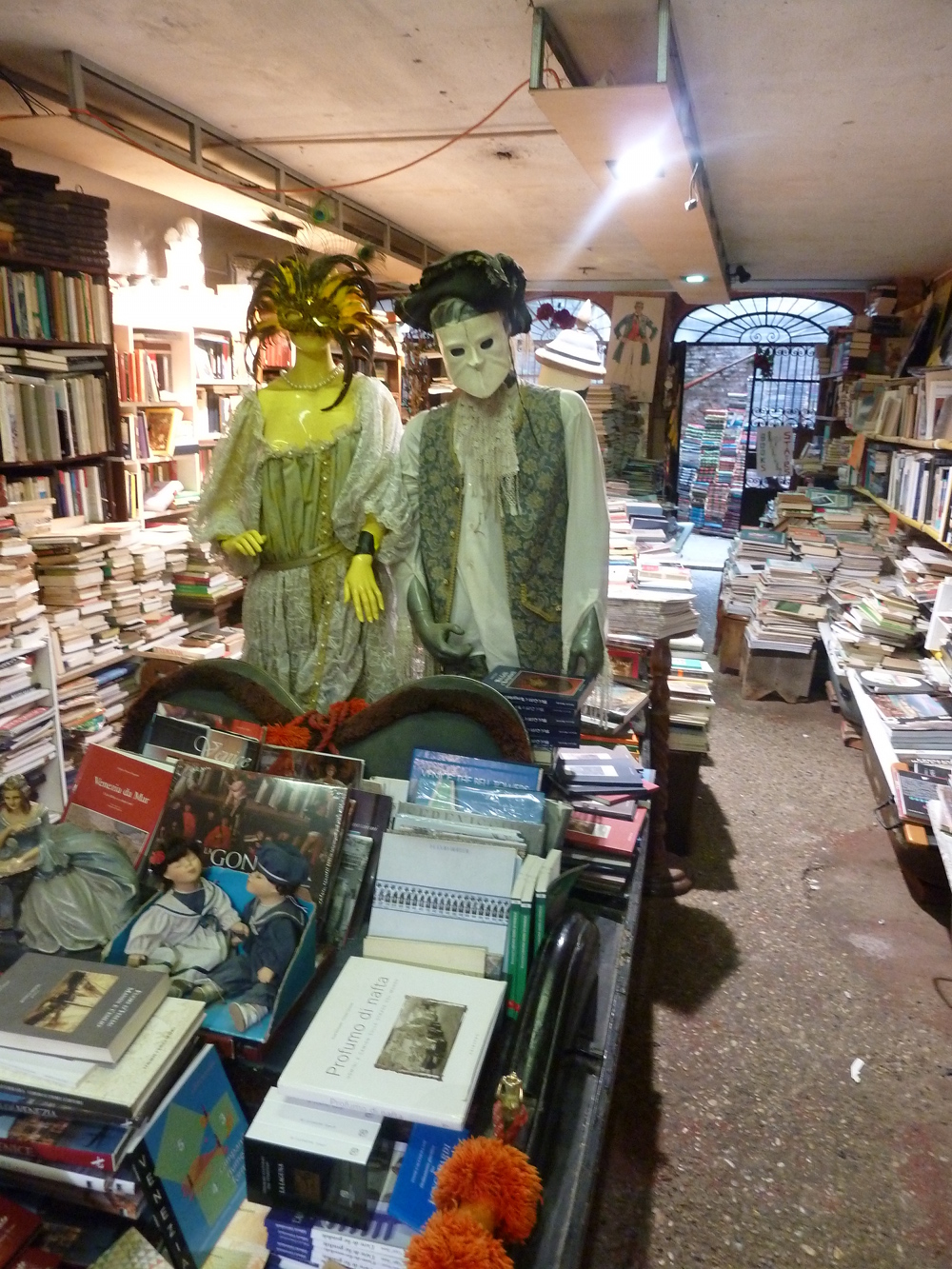

I managed to crawl my way out of last week’s all-pervading October fog – Dickensian or Hitchcockian, depending on the monsters looming out of it – to get to the Edward Burne-Jones exhibition at Kelmscott Manor.

The Body Beautiful: Burne-Jones At Work, was partly a goodwill gesture on behalf of The Tate, who carefully dismantled William Morris’ Kelmscott bed and took it to London for the Pre-Raphaelite: Victorian Avant-Garde show*. To be honest, I was expecting the Tate’s rejects. (“We’re having Love Among The Ruins. You can have this teacup.”) But the collection of hazy nudes and tactile studies, although small, was well worth the three-hour drive from Cambridge.

“It’s so flat that to see anything is not easy, and when you do see it, it isn’t worth seeing” – Rossetti, indulging in a grump.

For those of you who haven’t ventured out into the wilds of Lechlade to William Morris’ earthly paradise, let me first explain that Kelmscott exists inside a cosmic bubble. The modern world has been kept at such a distance, you can comfortably believe it no longer exists. The house and surrounding farm buildings have been preserved as sensitively as possible, encouraging visitors to see it as a home and not a museum. The weather is constantly mellow and glorious, and the carpark and the cafe are minor details – you can convince yourself that Morris has just pootled off to Iceland, and Jane is probably embroidering in the next room.

The illusion is compounded by little domestic details unfettered by velvet ropes. Rossetti’s satinwood writing desk (on wheels!) is so dinky, I wouldn’t get my legs under it. The general smallness of the house’s Victorian occupants was especially apparent in Morris’ overcoat, hanging from a door in the same room. Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Paris says the label, as if fresh off the catwalks. You can imagine him bustling about in it.

And then, upstairs…

The Body Beautiful: Burne-Jones at Work

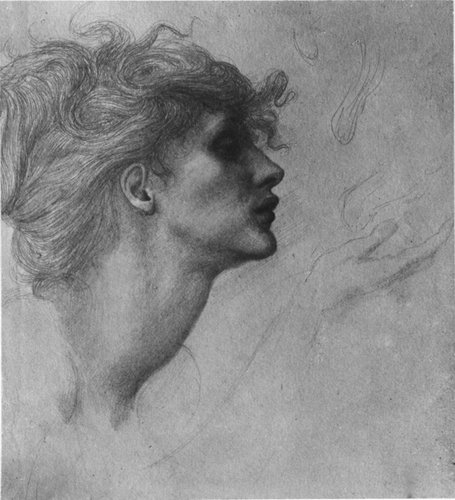

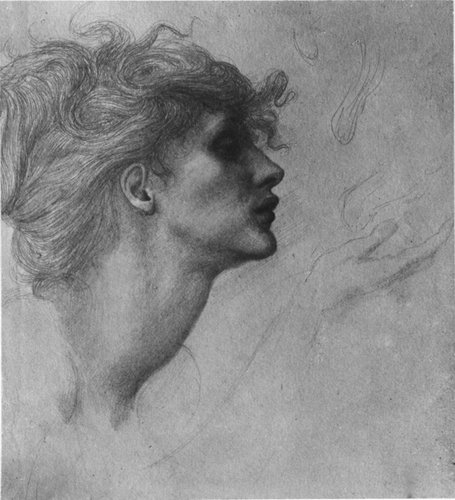

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

Of the small collection of studies, especially striking was the snake-necked Disiderium, the head of Amorous Desire, as dangerous as she is gorgeous. While some of the sketches looked scratched out and hurried, Disiderium oozes off the paper with the same anthropomorphic sensuousness present in Beguiling Merlin. More ‘the body bewitching’ than ‘the body beautiful’.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

It’s a shame the exhibition was so little-publicised, because fans of Ned would really have loved this, especially given the extraordinary setting.

The certain secret thing he had to tell

The certain secret thing he had to tell

Some of Rossetti’s worst illness and addiction was played out at Kelmscott, so it’s a sad place as much as a lovely one. When I last visited, I was in the midst of post traumatic stress disorder, and it was easy to see how the landscape of flat, marshy fields and slowly-flowing streams could be as much a help as a hindrance to someone suffering from an untreated mental illness. May Morris remembered him in his black cloak, “tramping away doggedly” across the landscape alone.

Jane, whose collected letters were published this month, doesn’t get much in the way of a ‘voice’ in comparison to the men at Kelmscott. Her job is muse. Embroiderer. In the dining room, I tried to imagine her as Burne-Jones described her at nineteen, laughing “until, like Guinevere, she fell under the table”, and found I couldn’t. Amusingly, on her bedside table today are the collected letters of noted drunkard and amateur sadist Algernon Swinburne, open on a page extolling “cannibalism as a wholesome and natural method of diet”. Oh, Algie, you card.

It’s amazing I ever got back in the car.

I have a bone to pick with The Society of Antiquaries.

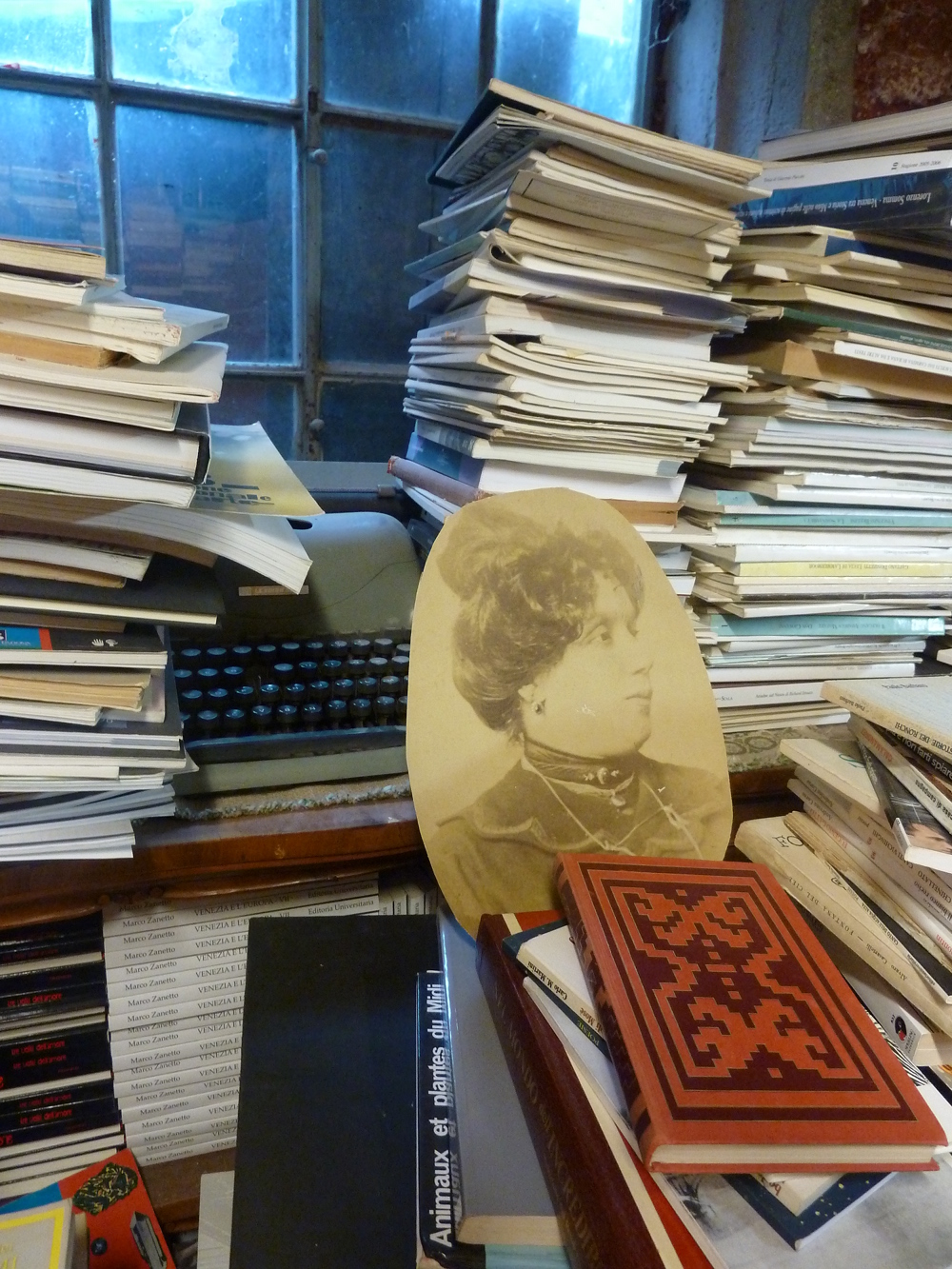

Rossetti’s bombsite of a paintbox resides upstairs in the tapestry room he commandeered for the light. In hilarious contrast to Millais’ pristine palette, Rossetti’s paintbox looks like something you’d find at the bottom of a skip. All his squeezed tubes (missing their tops, naturally) are congealed together in a shallow tin box encrusted with lead drippings, studio detritus, and a sort of greenish, yellowish coating of grotesquery and rust.

It’s gorgeous.

The room attendant, who very tolerantly said, “I’m touched you react that way” when I basically had a fit of the vapours over the thing explained the paintbox is a conservationist’s nightmare. Like Beata Beatrix, which was restored in time for The Tate, the paintbox contains a certain amount of ‘holy dirt’: original detritus from Rossetti’s studio. The trick is to separate the holy dirt from the decades of accumulated filth and decay without damaging the artefact. The trouble is, they haven’t started the process yet. And from the sounds of it, there are no plans to.

I wish I could share a photograph of it here, but photography is strictly forbidden. There are no postcards of the paintbox either, and because it isn’t labeled, half the visitors are walking by it without ever knowing what it is.

I feel the need to start a campaign. Look here, Society of Antiquaries, print some postcards, and put the proceeds towards protecting that precious paintbox!

* Before any Morris fans worry, the crew photographed each step of the disassembly, so not a single tiny, precious screw will be forgotten when the bed eventually returns.

Only a few more days until the general release of The Mighty Healer. All being well, there’ll be a launch evening at Holloway College itself on the 14th of November, where I’ll be signing books and lurking at the bar. More details as they’re finalised.

Only a few more days until the general release of The Mighty Healer. All being well, there’ll be a launch evening at Holloway College itself on the 14th of November, where I’ll be signing books and lurking at the bar. More details as they’re finalised.

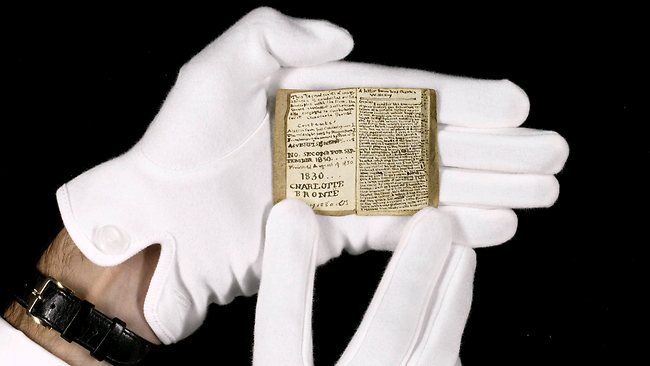

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape?

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape? Nailed it.

Nailed it.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy. Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence. The certain secret thing he had to tell

The certain secret thing he had to tell