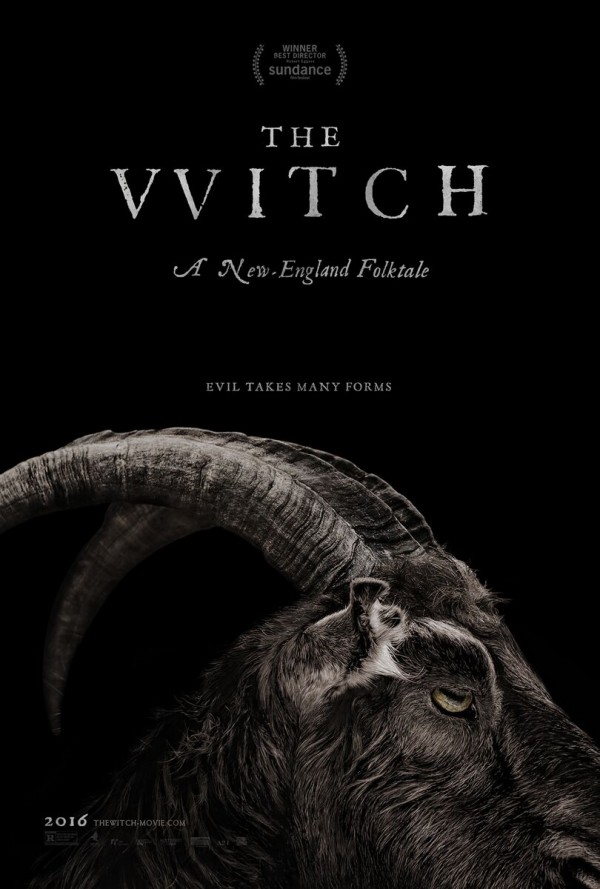

If you follow me on Twitter, you’ll know I’ve been excited about The Witch for weeks, and finally got to see it on Saturday. I loved it – loved it in a slightly manic, unreserved way, grinning in the dark for two hours despite the man behind me getting vocally upset because a film marketed as being disturbing turned out to disturb him.

If you follow me on Twitter, you’ll know I’ve been excited about The Witch for weeks, and finally got to see it on Saturday. I loved it – loved it in a slightly manic, unreserved way, grinning in the dark for two hours despite the man behind me getting vocally upset because a film marketed as being disturbing turned out to disturb him.

In summary: Puritans are awful, New England is awful, children are awful, that man sitting behind me who thought he’d come to see a Pixar film is awful… but goats just want to have fun.

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of Folklore Thursday, gather round and clutch your protective sprig of rosemary…

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of Folklore Thursday, gather round and clutch your protective sprig of rosemary…

I Saw Sister Procter Canoodling With The Devil

There have been cases of mass hysteria throughout history in all sorts of cultures and scenarios. Especially potent in close-knit communities like boarding schools, mild cases of mass hysteria can lead multiple individuals to laugh unstoppably, faint, contract an imaginary virus, or become convinced of a conspiracy. When the paranormal becomes involved, as the Salem witch trials show, things get rather more interesting.

One case in 1491 saw a nunnery in the Spanish Netherlands overrun with ‘possessed’ nuns. The sisters ran around like dogs, jumped out of trees pretending to be birds, and clawed tree trunks, miaowing. (Did the cat-nuns chase the bird-nuns, I wonder?) Devilish familiars were blamed, and over the following centuries, dozens of similar mass hysterias cropped up in convents all over Europe. Screaming, convulsing, foaming at the mouth, nuns would confess to carnal relations with devils and attempt to seduce those sent to exorcise them. For a bored nun who fancied her priest, succumbing to hysterics probably looked quite appealing. Or perhaps demons, like poltergeists, work best amongst stifled young women.

Your Honour, I Put It To You That Donkey Is Evil

As every good churchgoing medieval serf knew, Jesus drove a pack of demons out of a man and into a herd of pigs. The pigs subsequently hurled themselves into a river to drown. So it’s understandable, then, that animals were sometimes suspected by early modern humans of being up to something wicked. A Swiss cockerel in 1474 was burned at the stake for committing the “heinous and unnatural crime” of laying an egg. Such a disruption to the natural order had to mean Lucifer was playing tricks through the medium of breakfast food.

Animal trials sometimes involved actual courts, judges, and juries. In 1750, a donkey caught in the act of copulation with her human master was found innocent by the townspeople because she was “in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature”. The man was executed. In the French town of Savigny in 1457, a sow was put on trial for trampling a child to death. The sow was hanged from the same gallows tree as the town’s human criminals, but her piglets were exonerated due to lack of evidence.

Questions of free will clashed with theology in these animal trials – were animals empty vessels capable of being controlled by devils, or were they creatures with as much character and virtue as a man?

They Came From The Forest

Woolpit (meaning ‘the pit of wolves’) is a nice little village in Suffolk where I used to spend weekends with my aunt. She had a twelfth century house there with witch marks on the ceilings – long ladders and ave marias traced in tallow smoke. If you’ve driven through Woolpit, you’ll have noticed the peculiar village sign depicting one of the wolves the village is named for alongside two children, hand in hand, painted green.

Around the time my aunt’s house was built, a boy and a girl emerged from the woods. They spoke an unknown language, and both had green skin. The children would only eat beans, and the boy soon died. When the girl was taught enough English to communicate, she claimed to be from a world of eternal twilight called The Land of Saint Martin. They were wandering through a cave, she said, when they blundered into horrid daylight and were discovered by a gang of Woolpit reapers. They did not know how to get home.

The girl took the name Agnes, married, and lived a relatively normal life, eventually losing her green colouring. Various theories abound – that the children’s greenness was caused by Hypochromic Anemia, that aliens had landed, or that they were indeed faerie children from a sunless world.

Bugganes and Breeches

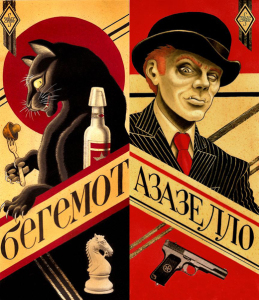

While faeries have it in them to be friendly on occasion, goblins err on the side of goatish bloody-mindedness. The Buggane, in particular, embodies this attitude. These pre-Christian goblins were known to set up camp in old chapels to prevent parishioners preparing leaky roofs and dangerous staircases. Able to change shape at will, Bugganes favoured the form of monstrously large black rams; the horns enabled them to actively rip down roofs so congregations were rained on during services.

One Buggane did just that when monks failed to ask permission of the faeries before building their church at the foot of Greeba Mountain on the Isle of Man. No matter how many times the roof was repaired, something gigantic would tear it off again, and soon no one dared worship there.

The destruction prompted a local tailor to make a bet that he could stay in the goblin-infested chapel long enough to make a pair of breeches. At midnight, the Buggane tired of the tailor’s company and appeared in its horned form, ready to give him its customary gigantic demonic ram welcome. The tailor was quick, however, and when the Buggane realised it couldn’t catch him, it ripped off its own head and flung it at him. As you do.

The chapel – St Trinian’s – remains a roofless ruin to this day. And horned farmyard animals remain peaceable and cuddly and only casually acquainted with Lucifer.

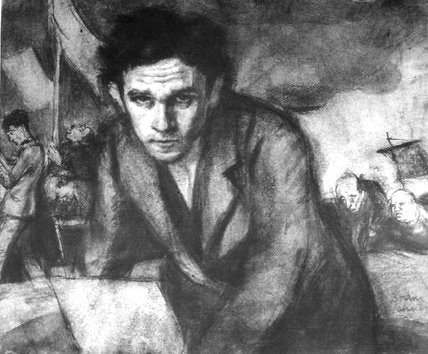

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,  He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

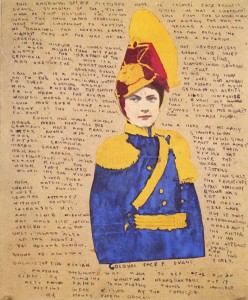

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

![Epitaph for Happiness (and Audrey) There’s not one curse or evil deed, No spells or promises to heed, There is no equal power within the mind Yes! Love’s happiness was hard to find [April, 1969]](http://verityholloway.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/canehillpoem.jpg)