I haven’t blogged much lately, have I? For a change, I have a solid excuse…

I had open heart surgery. Planned, elective, but still an enormous ordeal. I’m almost eight weeks post-surgery right now, and I’ve only just summoned the energy to write anything about it beyond the odd tweet.

Before I decided to get on the waiting list, I naturally went looking for people’s experiences. And though I found a few exceptionally lovely bloggers who held my hand and kept me going, there wasn’t that much out there from a young woman’s perspective. And sure, it’s a heart, we’ve all got hearts, but when you’re facing something so massive, so life-changing, it helps to be able to see other people like yourself who’ve been through the same and come out fighting.

If you Google ‘cardiac patient’, you’ll see plenty of this guy:

I’m 32 and I don’t own a pair of overalls. So I wanted to write a detailed guide from my perspective. I can’t promise it will be interesting to anyone with a healthy heart, but the one thing I wanted most of all before my surgery was someone to talk me through the nitty gritty so I’d go in feeling as informed as possible. Not everyone feels that way. One lady I met in the pre-admission clinic didn’t even want to know the name of her procedure, and that’s absolutely fine. Give this a miss if that sounds like you.

I’m 32 and I don’t own a pair of overalls. So I wanted to write a detailed guide from my perspective. I can’t promise it will be interesting to anyone with a healthy heart, but the one thing I wanted most of all before my surgery was someone to talk me through the nitty gritty so I’d go in feeling as informed as possible. Not everyone feels that way. One lady I met in the pre-admission clinic didn’t even want to know the name of her procedure, and that’s absolutely fine. Give this a miss if that sounds like you.

Obviously, this is my experience, not yours. I was told about countless things I needed to prepare myself for, and then they never happened. So just keep that in mind.

Regulars will know I have a connective tissue disorder called Marfan Syndrome. Put simply, Marfans means the tissue holding your body together is too elastic to do the job effectively. For Marfs, the whole body is delicate, but the heart most of all. People with Marfans are at high risk for aneurysms, and since I was a teenager I’ve been monitored with an annual MRI as my aortic root (the big part at the top of the heart) has been slowly getting larger and weaker. By age 31, my aortic root measured 4.5cm, double the healthy average. This is the measurement where surgeons recommend Marfan patients think about elective aortic root replacement.

I knew it was coming, but it was still a sickening surprise when my cardiologist referred me to a surgeon for ‘a chat’. It was even more surprising when a nurse took blood for a transfusion, measured me for DVT stockings, and handed me a consent form.

By the time the nurse was finished with me, I was dizzy with anxiety. With the consent form in my hand, I was ushered in to see my surgeon. It was all going so fast. I’d always told myself the surgery was years off. I had no symptoms. I was pretty fit for someone with my condition. I had DMs and a leather jacket, I didn’t need any bloody DVT stockings! Except I did. I actually did.

My surgeon was Samer Nashef at Royal Papworth. I liked him straight away. I’ve never felt comfortable with doctors who are evasive or try to make things fluffy for fear of overwhelming you, and Mr Nashef was willing to take me through everything in a matter-of-fact way that kept me calm and well-informed. I needed the David Procedure, which you can read about here. My heart would be ‘switched off’ and the enlarged section of my aorta would be removed and replaced with a synthetic tube. It would take around five hours, with thirteen weeks of recovery. “It’s huge,” the surgeon said. But I had youth on my side, and the best team in the country.

The choice was presented to me. I could carry on living my life, put off the surgery for a few years, but there would come a point where the risk of waiting outweighed the risk of the procedure, and that point would likely come soon. Some patients are lucky, some are not.

I went home to think about it.

*

From that day on, everything was about surgery. I couldn’t focus on anything else. Every ache and pain had me fighting back panic. I’d look at my chest in the mirror and envision the gnarliest possible scar. Worse, I had no instincts. I went back and forth on all the options, spoke to fellow patients, friends, family, read all I could on the subject, but still it seemed unreal. If the surgeon had simply said “Now is the time” it would all be so much less agonising. If I felt ill, even. In the end, I phoned Mr Nashef’s secretary partly to put an end to the tension. The waiting list was sixteen weeks, but at least I was on it.

Here follows a musical interlude lasting nine. whole. months.

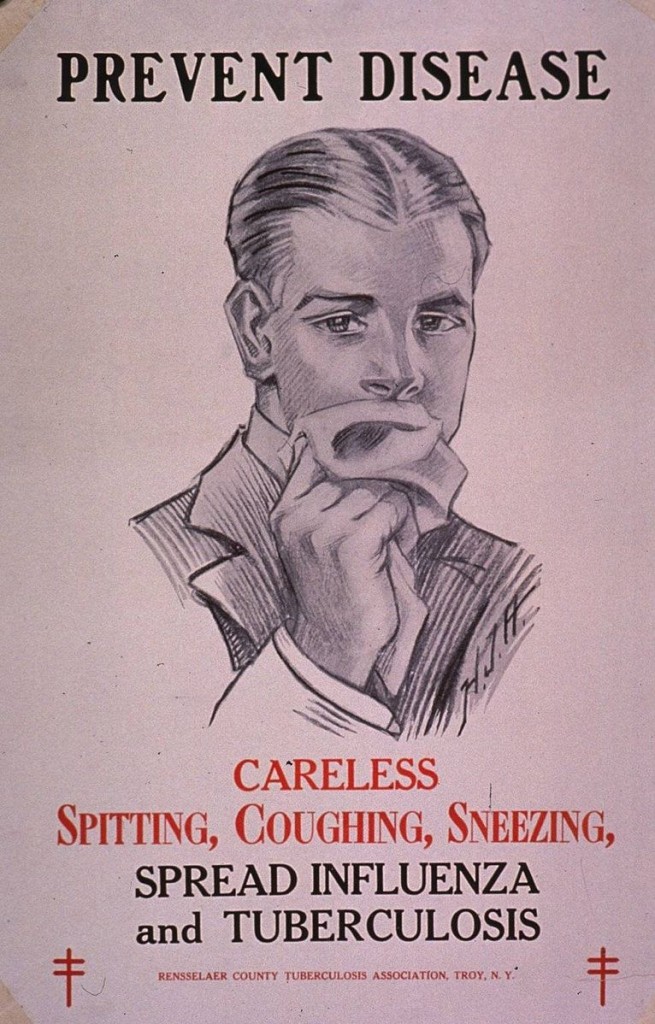

At the six month mark I got the call to come into Papworth for a pre-admission clinic. There I was weighed, measured for bloody DVT stockings again, had blood taken, MRSA swabs, stood for a chest x-ray, and spoke to my surgical team including the anaesthetist about what to expect. This took up most of a day, so when it’s your turn be sure to take snacks and a book. You’ll be presented with tubes of antiseptic gel to squeeze into your nostrils twice daily, and an equally appetising bodywash for the night before your procedure. You’ll be given a lot of paperwork, too, so it helps to have a folder to keep it all safe. Some of these papers are guides for family, including vital rules about visiting. The importance of Sniffling Cousin Jimmy staying away before and after surgery cannot be overstated. For two weeks before surgery, you can’t take supplements, and that includes vitamin C. Anyone with a cold needs booting out of the nearest window.

There’s a hell of a lot to take in at this stage, and even more to plan for. Prepare thyself. You’ll need to put a lot of thought into the reality of your recovery and spend a fair bit of money to make it as easy on yourself as possible. Remember, you’ll be working with a broken sternum. For a long time, you’ll be so tired even drinking a cup of tea will send you to sleep. How will you feed yourself? How will you wash? What will happen when your enormous husky wants a cuddle?

There’s a hell of a lot to take in at this stage, and even more to plan for. Prepare thyself. You’ll need to put a lot of thought into the reality of your recovery and spend a fair bit of money to make it as easy on yourself as possible. Remember, you’ll be working with a broken sternum. For a long time, you’ll be so tired even drinking a cup of tea will send you to sleep. How will you feed yourself? How will you wash? What will happen when your enormous husky wants a cuddle?

I needed, at the very least…

A tall, high-backed chair that could be moved from room to room

A recliner chair

A foam wedge for sleeping sitting up

Loads of button-up shirts, pyjamas and dresses

A single bed downstairs near the bathroom

A post-surgery bra

Cushions to protect my sternum when walking or using seatbelts

A travel bag for hospital with everything I needed, but nothing I’d mind losing

And the small matter of someone to look after me 24-hours a day for untold weeks

It turned out I had plenty of time to arrange all these things, because my surgery date was cancelled twice. Can’t be helped, but ugh… it was harsh. The first time, I was all set to go into theatre when two emergencies were blue-lighted in and I had to peel out of my paper knickers and go home. What do I do with myself now, I wondered? Getting back in the car that night was overwhelmingly strange after almost a year of revving myself up for the biggest physical challenge of my life. So I ordered a pizza and let my brain just shut down.

Depression is a major consideration when you’re going into a battle like open heart surgery. When you can’t make plans, can’t enjoy the present, or control your own future, you can’t help but go a little mad. I went numb for two weeks. I couldn’t read books or weather trivial daily annoyances. I’d wake up shouting. When my next date came a couple of months later, I promptly contracted a wisdom tooth infection. The mouth is an infection superhighway to the heart, so my surgical team told me to sit tight and get well. It was bad luck, putting it mildly. I felt like The Girl Who Cried Surgery.

My third date was April Fool’s Day. Ha. Ha! I’d believe it when I woke up on a ventilator. So when I rocked up to Papworth with my bag and my paperwork, part of me was coolly convinced I was about to go home again.

To be continued. Because I’m knackered.