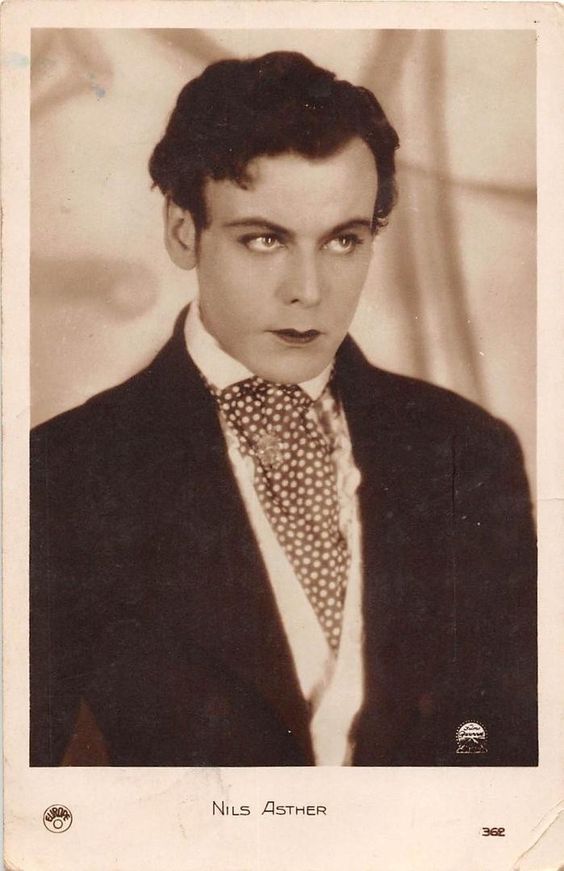

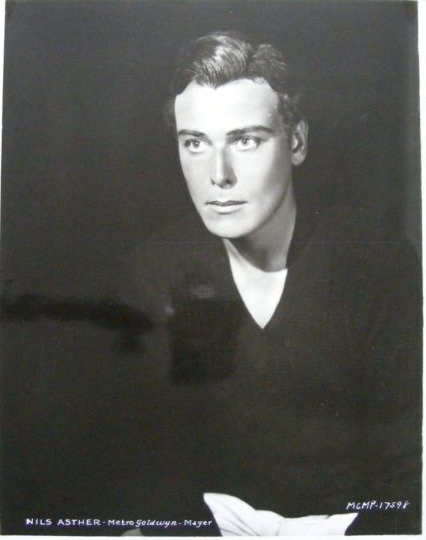

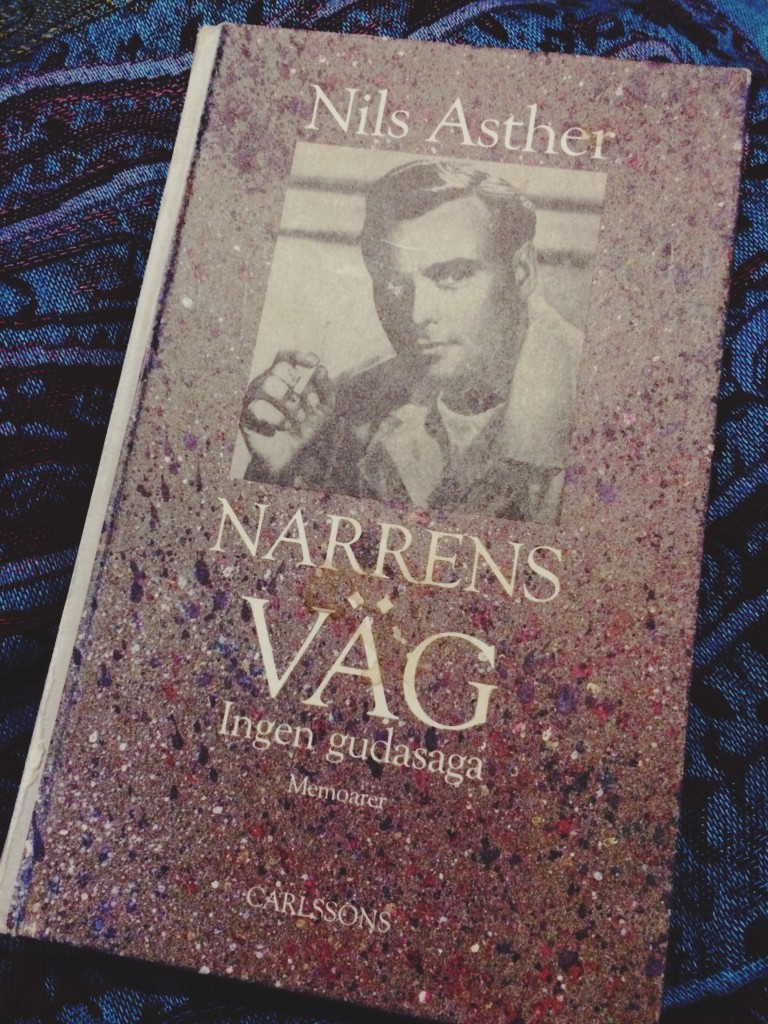

This instalment of The Fool’s Way, my summary of silver screen star Nils Asther’s memoirs, isn’t cheerful reading. Just so you’re forewarned. You can catch up on the previous part here.

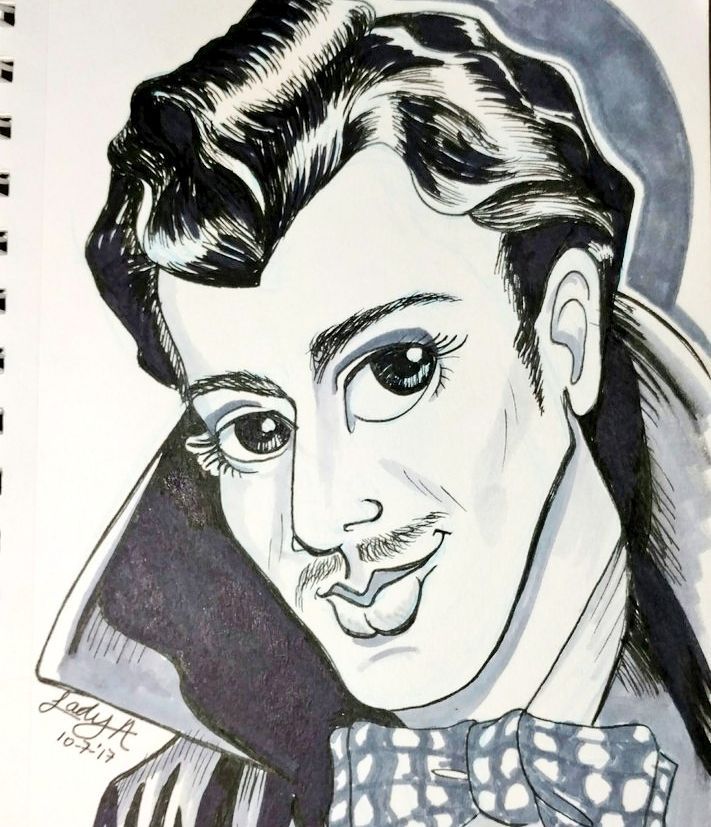

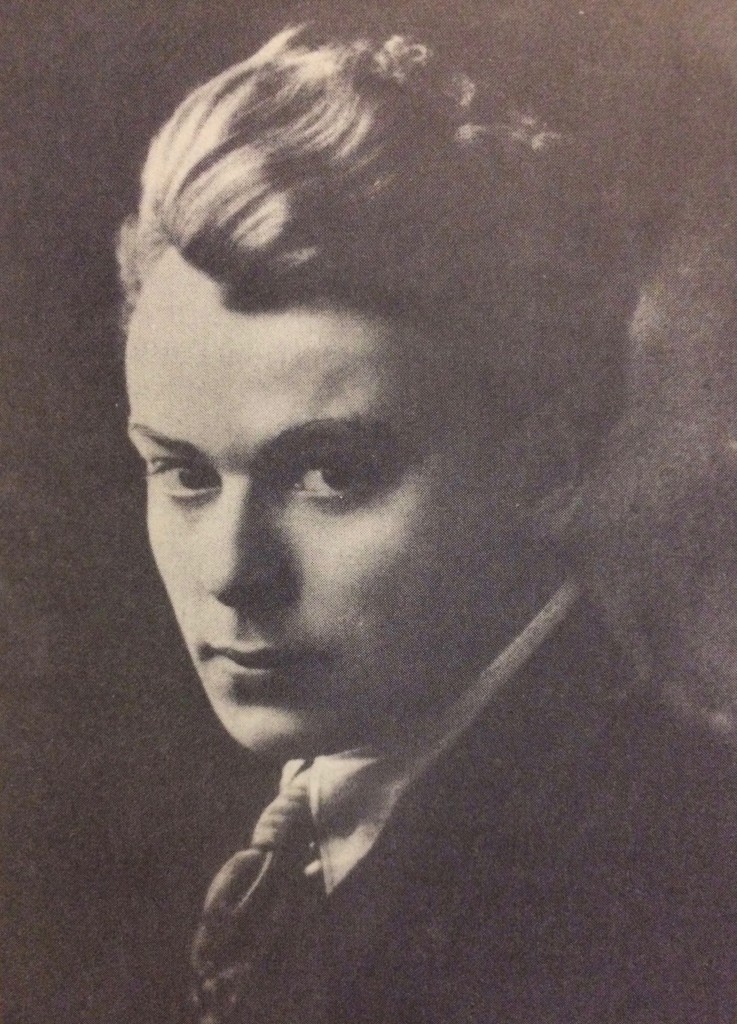

“Interviewing Nils is like interviewing twins,” wrote Myrtle Gebhart. “He delights in baffling you with his dual personalities.”

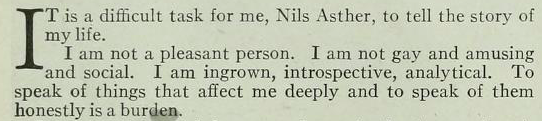

Reading his memoirs, you get that feeling. There’s the carefree Nils who’ll try anything once, especially if it’s risky, and then there’s his paranoid, self-loathing double. I don’t know exactly when he wrote his memoirs. They feel bitty, like he chipped away at them over the years and abandoned them a handful of times. But what’s crucial is that they weren’t published in his lifetime, and they were not published with his consent. The finished product contains a long post-script by his carers about living with Nils in the 1980s and all the trouble he got into (which I’ll talk about later, because oh boy it’s an epic). It feels like an intrusion. We see a deeply anxious man who feels he never had agency over his own life. Someone who longs for friendship but cannot imagine anyone seeing past his inherent brokenness. He worries himself into a frenzy over the things he had already written about with nonchalance. So why not destroy the manuscript? Did he need to write himself into existence, in his own words, even if those words scared him?

I’d love to ask, but I can only imagine him lighting a cigarette and slinking off.

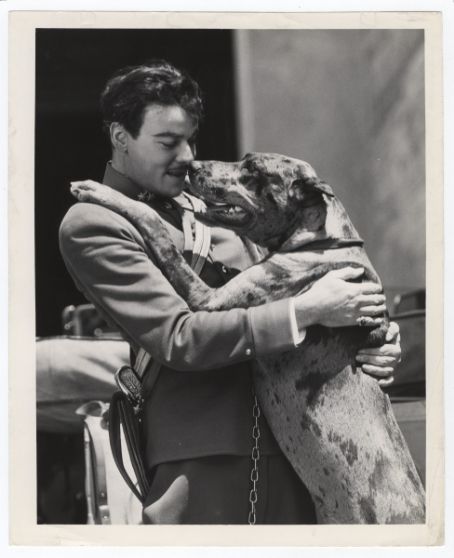

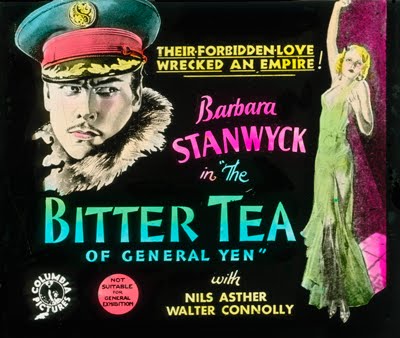

Back to the 1930s. General Yen had put him back in the public eye, especially in the eyes of young women who were the principal movie-goers. But Nils was still on thin ice, not that you would know from his interview style. “I don’t speak English”. “I have six women – a whole harem – in my home”. Studio embargo on interviews? He’d invite journalists personally. What about the fine MGM movies of his past? They were all dreck. Wondering why his house was so far away from all the other stars’? He was planning to live in the woods and bathe in the streams like Tarzan. Try and find him then, suckers.

Back to the 1930s. General Yen had put him back in the public eye, especially in the eyes of young women who were the principal movie-goers. But Nils was still on thin ice, not that you would know from his interview style. “I don’t speak English”. “I have six women – a whole harem – in my home”. Studio embargo on interviews? He’d invite journalists personally. What about the fine MGM movies of his past? They were all dreck. Wondering why his house was so far away from all the other stars’? He was planning to live in the woods and bathe in the streams like Tarzan. Try and find him then, suckers.

He could never resist throwing stones at the wasp’s nest.

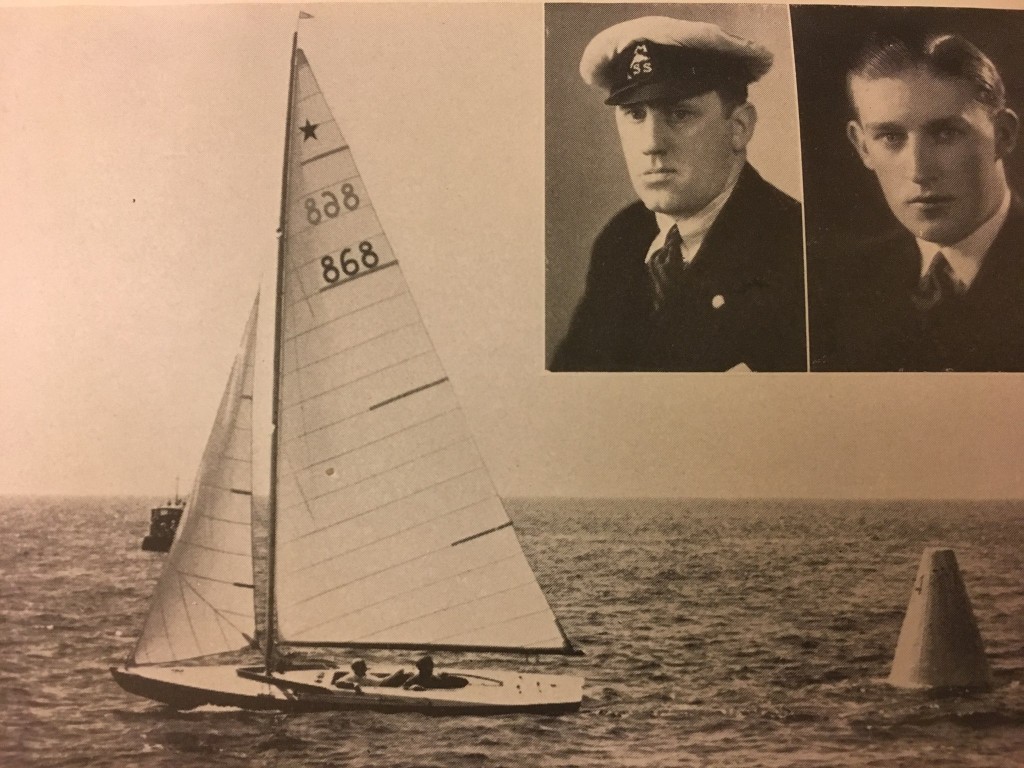

But the journalists who met him were charmed. He was a wry and suave host, and his ‘difficult’ nature was a breath of fresh air in the bell jar of Hollywood. Something delightful must have been going on in the young divorcee’s private life, they speculated, but they were dealing with an actor. By 1933, Nils’ obsession with adoption had mutated into something sadder. He convinced himself that somewhere his ‘real’ family were going on with their lives, glad to be shot of him. At night, he suffered panic attacks. Something was wrong with him, he told himself. Perhaps his real parents were crazy. Perhaps they knew he’d go the same way. In a weird coincidence, half-brother Gunnar Asther was in LA competing as a sailor in the 1932 Summer Olympics. All those long summer days on Evil Anton’s boats paid off, and he took a bronze medal for Sweden. Whether Gunnar looked up Nils while he was there, I don’t know. Considering Anton deliberately excluded Nils from those father-son boating trips, the whole thing would have been a painful spectacle.

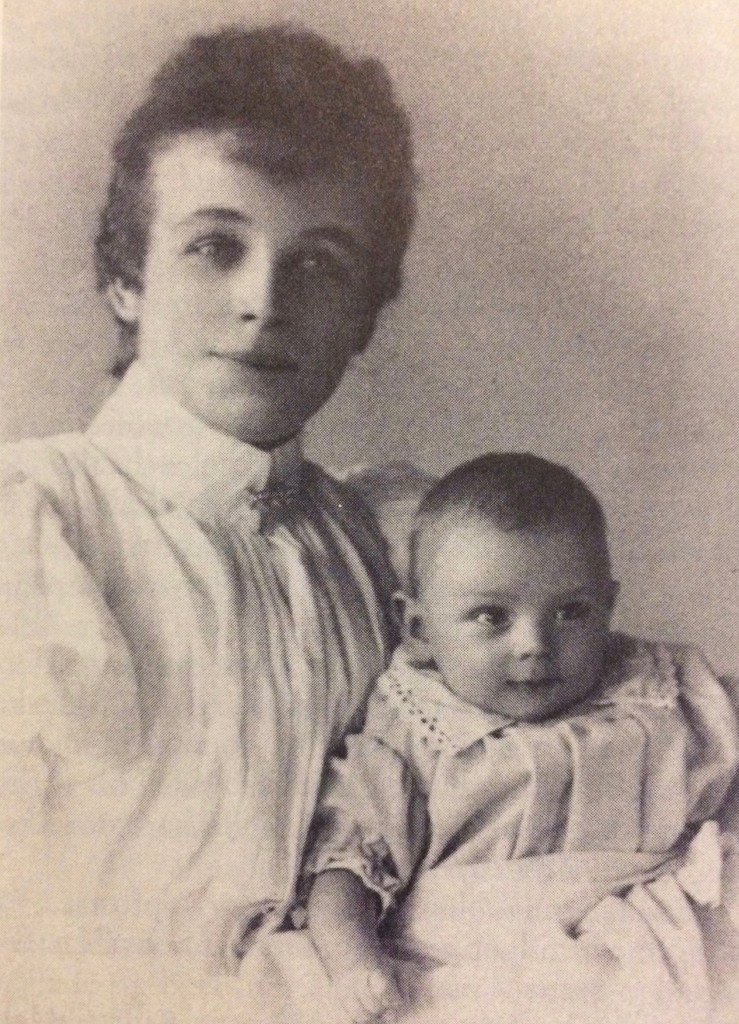

Hilda, too, had come over from Sweden to inspect her son’s bride. She knew a miserable marriage when she saw one. At the divorce hearing, Vivian complained that her mother-in-law called her rude names in Swedish, but Hilda, like her son, could be cool and imperious to strangers. She was the same way with him; further proof, in his mind, that she wasn’t his biological mother despite their shared, distinctive beauty.

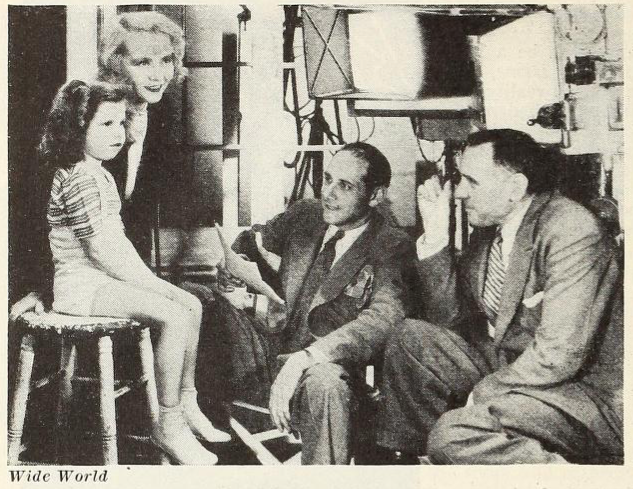

Bad marriages screw people up. They screw children up, especially. When little Evelyn was put on the stage in frilly skirts and tube socks, Nils was upset. Evelyn was being manoeuvred by movie professionals while too young to understand what she was giving up, like her vaudeville dolly mother before her. Like him.

Hollywood was a nightmare merry-go-round, and there was no getting off.

In typical style, Nils shacked up with a 22-year-old Korean dental student straight after the divorce. The lad was promptly arrested for trying to forge Nils’ signature. Nils had a habit of throwing money at his lovers, and it’s entirely possible he gave the student a blank chequebook to play with. Louis Mayer exploded. Nils was one of those ‘dual-sex boys and lesbos’ (his words) who needed driving out of Hollywood.

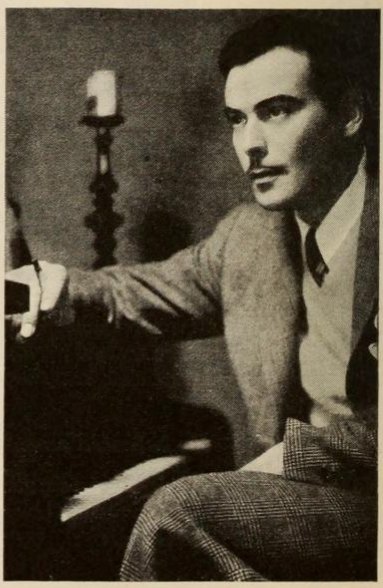

Well, fine. He never wanted to be in Hollywood anyway. He returned to Europe where he could run away to Paris or Vienna at a moment’s notice, just the way he liked. In England he had fun as Jean Varenne in The Prisoner of Corbal, a daft French Revolution romance and probably my favourite of his films. Varenne is sardonic and sexy, parading about with a whip and a sneer, and the cross-dressing love triangle at the heart of the story gives the film a sexual ambiguity Nils is clearly revelling in. He became very thin for the role, and with his height he resembles a monochrome David Bowie. It’s the kind of fun he was never permitted in America.

The Prisoner of Corbal opened the door to more fun roles as WWII came and went. In The Man on Half Moon Street, he plays a noir Dorian Grey plucking failed suicides from the London fog before harvesting their “glaaaaands” for the elixir of eternal life. A Right to Romance, although another candy floss romantic role, called for him to be scruffy. Women wrote to threaten that if he didn’t smarten up, they’d boycott his next work. He was breaking out of his mould. He could ditch the moustache. It was a joy.

But in Hollywood, someone had not forgotten the star who defied him.

Brewing in the background like a staph infection was Eddie Mannix, who you might remember from such atrocities as the car crash that killed his wife, the bullet in George Reeves head, and the annihilation of dancer Patricia Douglas after her rape by studio executive David Ross.

A pox on him and his weak chin.

Rumours had been popping up in movie magazines for more than a decade, all sanctioned by Mannix, and they’d slowly grown more outlandish. Where first a gossip columnist would delicately question why Nils Asther wasn’t satisfied by his pretty wife, now papers baldly stated he’d been spotted sunbathing naked on a roof with a man. Nils looked at the gossip with the contempt it deserved. “I was not going to let them crush me,” he wrote. When he returned to Hollywood in the mid-nineteen-forties, he fell straight back into his habit of cruising the boulevards. There were sailors drifting around like litter, and soon he was seeing one regularly. Marlon Brando’s early body double, no less. Well done, Nils. It was a middle finger to the studios and their drive to rid the industry of homosexuals. Worse, it was an insult to Mannix.

Despite the enduring affection of audiences, work was not forthcoming. Someone started a rumour he’d killed himself. Another said he dyed his hair and walked with an old man’s stoop. The punishing behaviour of the studios took a dark turn – now he was offered mainly Nazi roles. They knew full well it pained him that his birthplace Denmark had been invaded.

Nils liked the freedom to vanish, so he kept a little apartment in Philadelphia away from the movie world. There he could do odd jobs to pay the rent – truck driving, delivering post. It was bizarre to onlookers, but he loved those $1 an hour jobs. They were nowhere near as miserable as having to play Nazis. It was there that he was contacted to write and direct a commercial. It was work. Why not?

A private villa. A sunny day. He was met at the door by a young man in swim shorts, soaking wet and smiling.

He was led out to the garden, given a glass of juice and told his contact would be out in a moment. Would he like to swim? There were spare shorts he could borrow. Nils declined. It was an unseasonably beautiful day. Waiting in the sunshine was no hardship.

He waited. The boy swam. No one came.

Something felt wrong. The juice reeked of booze. He put the glass down just as the boy got out of the pool and settled down beside him. Then time seemed to speed up.

The boy grabbed Nils’ hand and pressed it to his crotch. Men appeared from nowhere. They saw him try to molest the boy. They would tell the press and the police. All he had to do was write them a blank cheque the way he had for his Korean dental student and then they would let him take the boy upstairs. Swimsuit boy protested. No one had told him that was the plan. But these were gangsters*. The plan was whatever benefited them.

Nils said no. Of course he said no. So they beat him almost unconscious.

Bleeding and retching, he had to hitchhike home. When he finally arrived at his flat, he realised he couldn’t live there anymore. The gangsters would find him.

It took twenty-four hours to gather the strength to leave the flat, and when a neighbour saw the state of him him he insisted Nils see a doctor. The next humiliation was that he couldn’t pay. What with the stock market crash, he hadn’t much money to begin with, and a call to the bank confirmed the thieves had taken everything without delay. All those little dollars earned driving a truck. A doctor friend of the neighbour confirmed his liver was hugely swollen and he needed urgent, expensive care. Nils took himself home and prepared an overdose of sleeping tablets.

Remember Anna Q Nilsson? He still wore the ring she gave him all those years ago. The two Swedes had barely seen each other during the war, and ‘Beloved Anna Q’ was much changed. A horse riding accident rendered one leg a full six centimetres shorter than the other, and she needed a brace to walk. Unlike Nils, Anna had made shrewd investments and survived the stock market crash pretty comfortably. She had tried to persuade Nils to follow suit, but he was never the type to take good advice – one of the reasons she wouldn’t marry him. At their last meeting, just before he left for Philadelphia, Anna told Nils to fight back. Get in a Rolls Royce and do a tour of the biggest names. Tell them you’re staying your fond farewells before quitting the business. She guaranteed the directors would be snivelling at his door by morning. Nils only laughed. How about I get in a Rolls Royce and drive around telling everyone to shove it? he said.

Remember Anna Q Nilsson? He still wore the ring she gave him all those years ago. The two Swedes had barely seen each other during the war, and ‘Beloved Anna Q’ was much changed. A horse riding accident rendered one leg a full six centimetres shorter than the other, and she needed a brace to walk. Unlike Nils, Anna had made shrewd investments and survived the stock market crash pretty comfortably. She had tried to persuade Nils to follow suit, but he was never the type to take good advice – one of the reasons she wouldn’t marry him. At their last meeting, just before he left for Philadelphia, Anna told Nils to fight back. Get in a Rolls Royce and do a tour of the biggest names. Tell them you’re staying your fond farewells before quitting the business. She guaranteed the directors would be snivelling at his door by morning. Nils only laughed. How about I get in a Rolls Royce and drive around telling everyone to shove it? he said.

He didn’t call Anna when he laid out his sleeping pills. Instead he phoned a University tutor he knew casually: Margareta Olsen-Krensiski. He was sure she wouldn’t swoop in with optimism the way Anna would, and gave her some basic funeral instructions. Toss his ashes anywhere, he said. He didn’t care. And maybe pray for him. There was another way, Margareta said. Come with her back to Sweden. There was a shortage of older male actors there, and she knew a friendly Jewish family who would be happy to help him settle in. There was social security in Sweden, attitudes were more permissive. Did he not know actors received a pension there? The problem wasn’t him, it was America.

We have Margareta to thank for talking him down. Nils had always loved escaping, and suicide was an extension of that coping mechanism. So no, he didn’t overdose that night. He gave away almost everything he owned, put the essentials in a single suitcase, and turned his back on the nightmare merry-go-round.

But it’s not the end. Not yet.

* I’m not saying Eddie Mannix definitely ordered the crime. I’m certain there were plenty of gangs out to extort money from gay actors, and with all the open secrets that kept Hollywood running, it couldn’t have been hard to pick a mark. But at the very least, Mannix laid the groundwork for violence in full knowledge of what might happen. If he was directly responsible, I wouldn’t be surprised in the least. The toad.

* I’m not saying Eddie Mannix definitely ordered the crime. I’m certain there were plenty of gangs out to extort money from gay actors, and with all the open secrets that kept Hollywood running, it couldn’t have been hard to pick a mark. But at the very least, Mannix laid the groundwork for violence in full knowledge of what might happen. If he was directly responsible, I wouldn’t be surprised in the least. The toad.

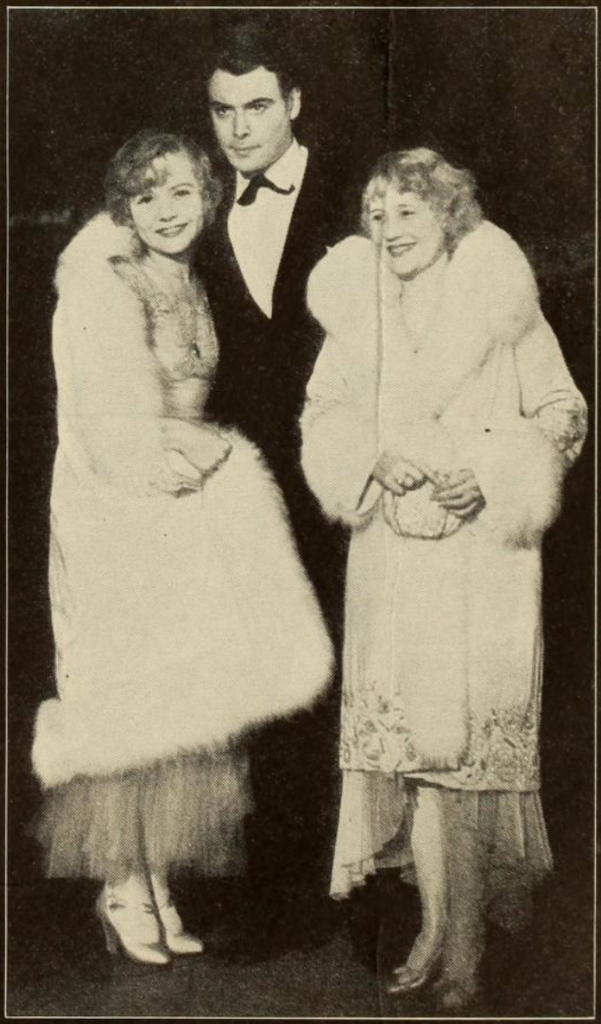

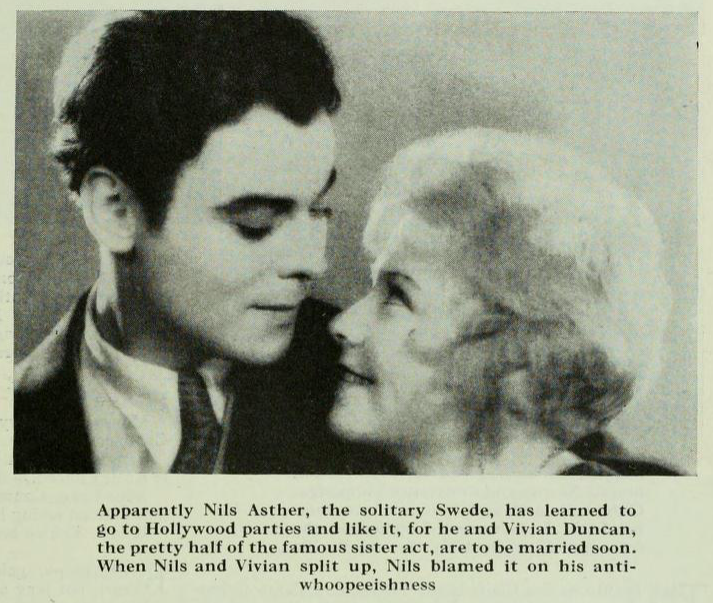

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

As we’ve seen, trying to tell Nils to behave was… a daring choice. He resisted the marriage for as long as he could. Years, in fact. The studios spun his stubbornness as an on-again-off-again love affair, a clash of American exuberance and Scandinavian… well, fjord-pining. Vivian joked they intended to keep the engagement chugging along until 1940. She held up her side of the bargain valiantly, no doubt concerned for her sister.

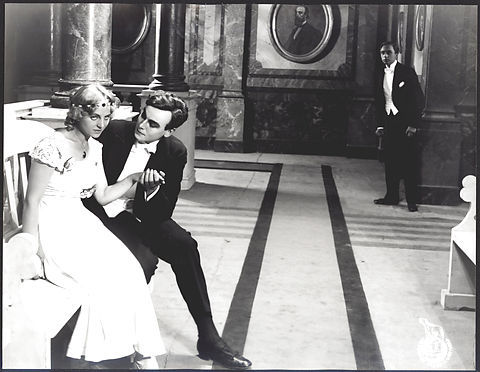

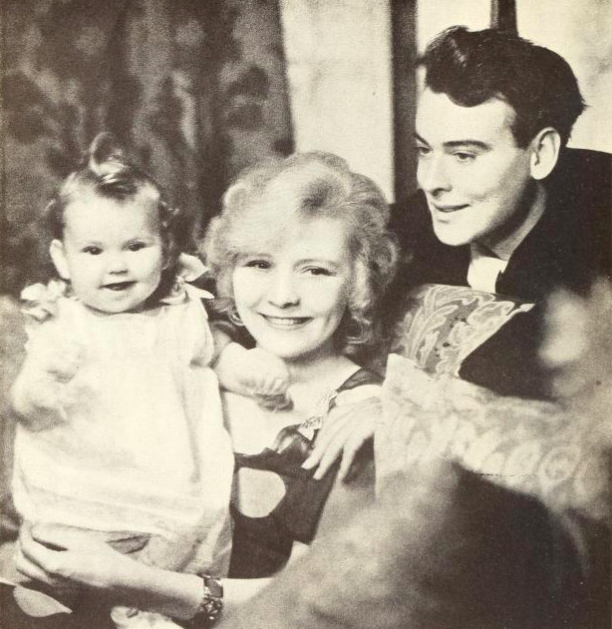

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

Look how pretty and desperately unhappy they all are.

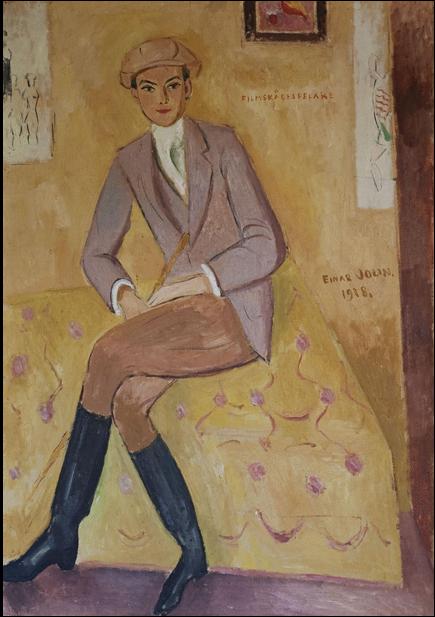

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.

When we last saw Nils, he was heading for Hollywood for either the time of his life or an unmitigated nightmare, depending on who you believe; Nils, or the people who sent him there.