My short story, Cremating Imelda, is published in Animal Literary Magazine this month. Imelda, a modern hermit in an abandoned village on the Norfolk coast, is a woman with a morbid talent concerning food – and mortal sin.

This is an old fascination of mine: the links between death, what we eat, and why.

For centuries, sin-eating was a funerary tradition grudgingly tolerated by The Church. Usually a reviled individual on the edge of society, the sin-eater went to funerals and ate bread or cake off the coffin, absorbing the deceased’s sins and thus allowing them to speed through purgatory. Presumably, they hoped someone would do the same for them, when the time came.

Sin-eating has long fallen out of favour. But there are more recent funerary traditions involving food that still manage to make us uncomfortable. A childhood memory: a Greek holiday. I was permitted one treat; anything I chose from the bakery. This bakery was nothing like the ones in England. There wasn’t a single stodgy pink bun or unhappy gingerbread man. Every confection was a miniature ornament sprinkled with green pistachio, or shining with honey. But what I wanted was inside a glass cabinet. A dish piled with plain brown biscuits. Just flat brown rounds of dough – nothing to excite a child. Perhaps it was because they were behind glass and therefore forbidden. I knew what I wanted, and I asked for it.

“Those are not for little girls. Those are for… for…” The baker wheeled her hands, searching for the English. “The funeral.”

Get the child away from the death biscuits. This was a Greek custom, the baker told us. Sweets to eat in the presence of the dead. Looking at the mountain of biscuits, I remember thinking the locals must have been dropping like flies. I ended up with some unmemorable cake or other, and the episode went down as further proof that Verity always was ‘a grimly kid’ (to borrow Rossetti’s phrase). But the idea of funeral biscuits fascinated me. Why didn’t we do this in England?

Food has become the awkward aftermath of the funeral service. I find myself in church hall kitchenettes, spending a great deal of time nibbling dismal supermarket own-brand Jammie Dodgers because it gets me out of talking to anyone. I’ve already stipulated I want gin served at my funeral, partly because everyone secretly hates those undersized cafeteria cups of tea, and also because I think a funeral is a place for a sort of human communion. “Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me.”

The Nourishing Death blog is a brilliant resource for anyone interested in the ways people all over the world honour their dead with food. Because food, in a ritual setting, is communication. In Funeral Festivals in America, Jacqueline S. Thursby writes of the funeral biscuit’s role in the Victorian way of death in the USA’s Pennsylvania:

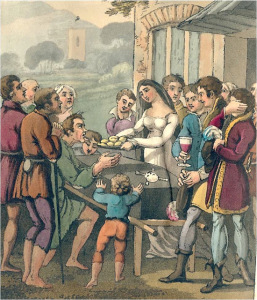

…a prevailing funeral custom was that a young man and young woman would stand on either side of a path that led from the church house to the cemetery. The young woman held a tray of funeral biscuits and sweet cakes; the young man carried a tray of spirits and a cup. As mourners passed by, they received a sweet from the maiden and a sip of spirits from the cup furnished by the young man. A secular communion of sorts, these were ritual behaviors that transcended countries of origin and melded a diverse young nation with the common cords of death, mourning, and tradition. The funeral biscuit served as part of a code representing understood messages of mourning, honor, and remembrance.

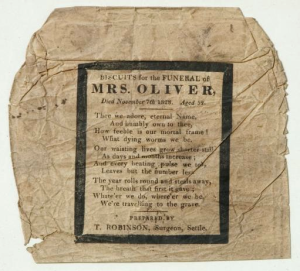

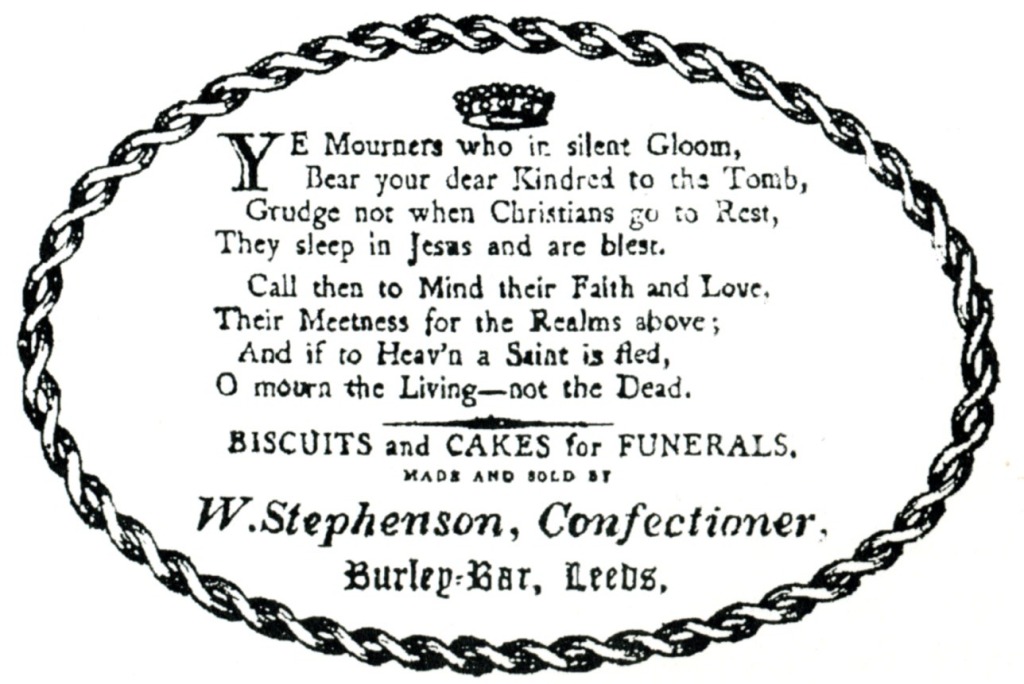

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

All flesh is grass. Enjoy your biscuit.

It’s little wonder such unflinching morbidity is unwelcome in the sanitised funerals of the modern world. But many European cultures still hold on to the funeral biscuit. In 2011, a Greek family were accidentally fed cocaine-sprinkled funeral biscuits, leading to what sounds like a lovely service:

The elderly bystanders, instead of mourning, began to dance around the dead, and the tears turned to nervous laughter. The cognac was consumed in shots accompanied by the sound of happy toasts, and there were some who started ordering mojito cocktails.

So what do you have planned for your send-off? If you could have a sin-eater come to wipe away your deeds, would you?

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

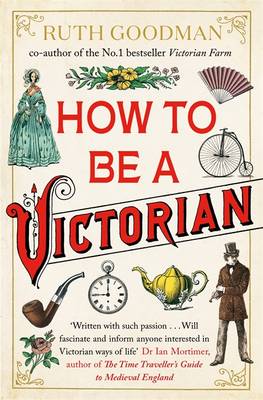

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics. Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

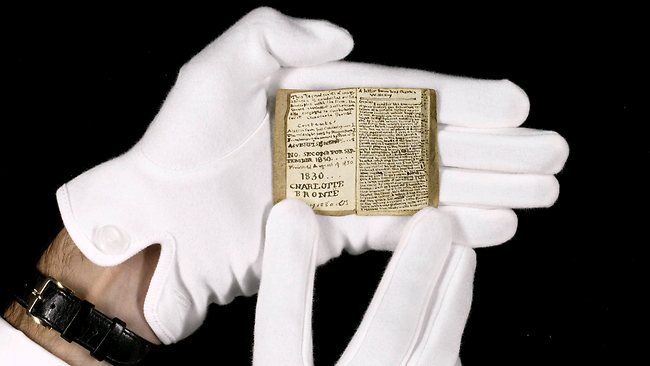

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises. The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.