My short story, Cremating Imelda, is published in Animal Literary Magazine this month. Imelda, a modern hermit in an abandoned village on the Norfolk coast, is a woman with a morbid talent concerning food – and mortal sin.

This is an old fascination of mine: the links between death, what we eat, and why.

For centuries, sin-eating was a funerary tradition grudgingly tolerated by The Church. Usually a reviled individual on the edge of society, the sin-eater went to funerals and ate bread or cake off the coffin, absorbing the deceased’s sins and thus allowing them to speed through purgatory. Presumably, they hoped someone would do the same for them, when the time came.

Sin-eating has long fallen out of favour. But there are more recent funerary traditions involving food that still manage to make us uncomfortable. A childhood memory: a Greek holiday. I was permitted one treat; anything I chose from the bakery. This bakery was nothing like the ones in England. There wasn’t a single stodgy pink bun or unhappy gingerbread man. Every confection was a miniature ornament sprinkled with green pistachio, or shining with honey. But what I wanted was inside a glass cabinet. A dish piled with plain brown biscuits. Just flat brown rounds of dough – nothing to excite a child. Perhaps it was because they were behind glass and therefore forbidden. I knew what I wanted, and I asked for it.

“Those are not for little girls. Those are for… for…” The baker wheeled her hands, searching for the English. “The funeral.”

Get the child away from the death biscuits. This was a Greek custom, the baker told us. Sweets to eat in the presence of the dead. Looking at the mountain of biscuits, I remember thinking the locals must have been dropping like flies. I ended up with some unmemorable cake or other, and the episode went down as further proof that Verity always was ‘a grimly kid’ (to borrow Rossetti’s phrase). But the idea of funeral biscuits fascinated me. Why didn’t we do this in England?

Food has become the awkward aftermath of the funeral service. I find myself in church hall kitchenettes, spending a great deal of time nibbling dismal supermarket own-brand Jammie Dodgers because it gets me out of talking to anyone. I’ve already stipulated I want gin served at my funeral, partly because everyone secretly hates those undersized cafeteria cups of tea, and also because I think a funeral is a place for a sort of human communion. “Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me.”

The Nourishing Death blog is a brilliant resource for anyone interested in the ways people all over the world honour their dead with food. Because food, in a ritual setting, is communication. In Funeral Festivals in America, Jacqueline S. Thursby writes of the funeral biscuit’s role in the Victorian way of death in the USA’s Pennsylvania:

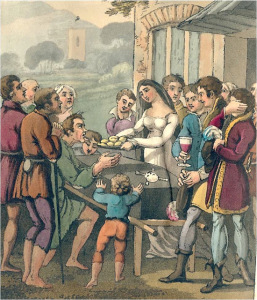

…a prevailing funeral custom was that a young man and young woman would stand on either side of a path that led from the church house to the cemetery. The young woman held a tray of funeral biscuits and sweet cakes; the young man carried a tray of spirits and a cup. As mourners passed by, they received a sweet from the maiden and a sip of spirits from the cup furnished by the young man. A secular communion of sorts, these were ritual behaviors that transcended countries of origin and melded a diverse young nation with the common cords of death, mourning, and tradition. The funeral biscuit served as part of a code representing understood messages of mourning, honor, and remembrance.

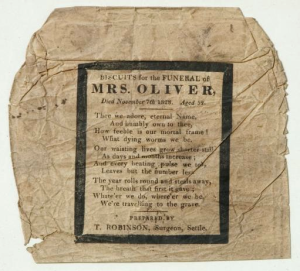

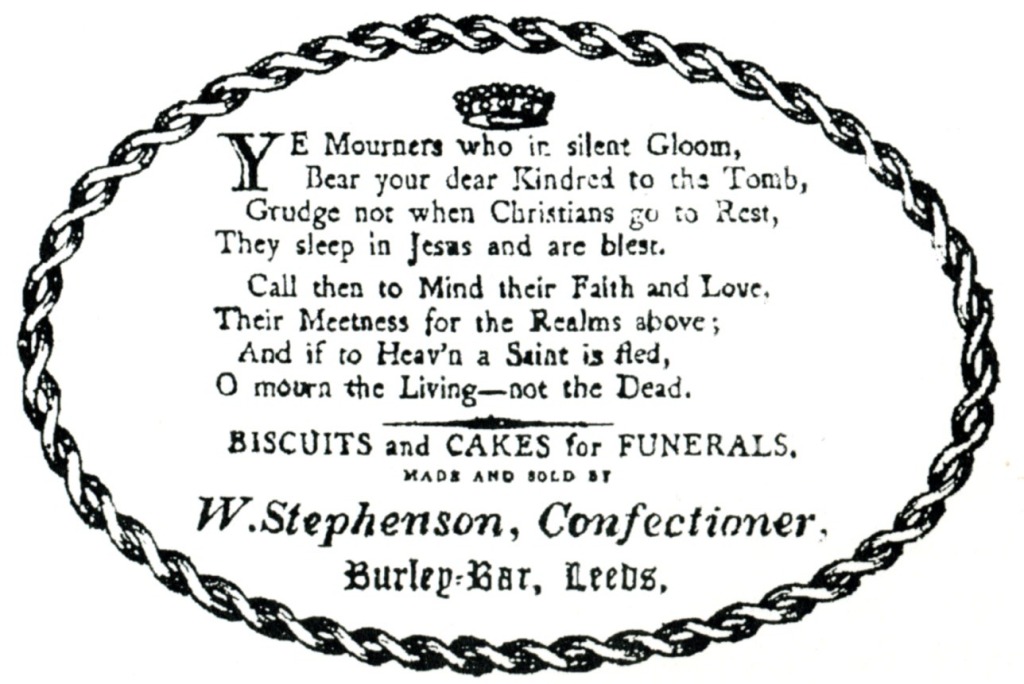

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

All flesh is grass. Enjoy your biscuit.

It’s little wonder such unflinching morbidity is unwelcome in the sanitised funerals of the modern world. But many European cultures still hold on to the funeral biscuit. In 2011, a Greek family were accidentally fed cocaine-sprinkled funeral biscuits, leading to what sounds like a lovely service:

The elderly bystanders, instead of mourning, began to dance around the dead, and the tears turned to nervous laughter. The cognac was consumed in shots accompanied by the sound of happy toasts, and there were some who started ordering mojito cocktails.

So what do you have planned for your send-off? If you could have a sin-eater come to wipe away your deeds, would you?

Clearly, cocaine for the elderly at funerals is the way forward!

I had been wondering if funeral biscuits were something to do with the wake – that our sandwich selection and swiss roll slices from Tesco were harking back to that. But then the funeral biscuit itself is related to sin-eating? I think the link with holy communion / mass is very relevant – death and food have had a long connection! I suppose sugar skulls on Dia de los Muertos is another link – and maybe even all that food found in ancient burials, preparing the dead for their journey into the afterlife.

Were sin-eaters already ostracised from their communities before they turned to that role? Because I’m wondering why you would choose to be your communities sin-eater, unless you had a sort of masochistic mindset and felt you deserved to consume everyone’s sins and be ostracised as a result?

I wonder if other people in the community, involved with the funereal process, became sin-eaters? For instance, when affidavits survive from the “you’ll get a fine if you’re not buried in wool” act, which include the names of those preparing the dead, they’re often widows and old women, who are on the edges of their society already. “Widow Boxstead gave oath that William Watts was buried in woollen cloth only.” Although sadly no note to say if she ate a biscuit to represent his sins…..

I saw a film recently, with Heath Ledger in it – The Order – and they gave the sin eaters some background lore. All the sin goes inside the sin eater himself, who then passes it on to his successor, and so on. And they live for hundreds of years in vast luxury, presumably given to them by the devil. It’s a fun, daft film.

From what I’ve seen, people happy to ‘eat’ sin were just people who were hungry and not an ‘important’ part of the community. So migrants, the destitute, etc. Because it was a bit of a dodgy practise, as far as the Church was concerned, it mostly seems to have gone undocumented. But I have read that the traditional Irish wakes are very close to the sin-eating tradition. There would be a communal toast taken from the coffin in some instances, and jokes about tricking the devil, harking back to the spiritual loophole of taking sin away via food.