I’m obsessed with History’s drama series, Vikings. I only started watching because I enjoy a bit of the old ultraviolence, but now I’m emotionally involved to an embarrassing degree and spend my time praying for Athelstan’s safety. That poor child has been through enough. All the hacking and slashing has piqued my interest, but, as fans of the show have pointed out, Vikings is only tenuously based on real events. We visited The British Museum’s wildly popular new exhibit – Vikings: Life and Legend – to learn more.

Were the Vikings one gigantic black metal band, or a culture as nuanced and refined as any other? Life and Legend doesn’t try to force you into either camp. What it does do is present the way the Northmen interacted with the cultures they encountered – the Franks, the Slavs, the Anglo-Saxons and beyond – and the evidence isn’t always what most visitors are expecting. Surviving poems prove it wasn’t all about violent conquest:

What’s this talk of going home?

My heart is in Dublin,

And the women of Trondheim won’t see me this autumn.

The girl has not denied me pleasure-visits, I’m glad;

I love the Irish lady as well as my young self.

– Magnus ‘Barelegs’ Olafsson, king of Norway (11th century)

These and other fragments challenge the image of the Viking people as marauding beasts. Sometimes they feel strangely familiar. Take, for instance, this public health announcement:

A man shouldn’t clutch at his cup, but moderately drink his mead.

A thousand years on, and Europe still isn’t listening.

However, if it’s indiscriminate bloodshed you’re after, there’s a lot to take in. We handled a 10th century axe-head, which the attendant helpfully informed us “was for killing people”. Then there was the absolute cutting-edge of weapon technology: Ulfberht swords. So powerfully made and sought-after were Ulfberhts, counterfeits were churned out like dubious Rolexes. There’s a documentary on Youtube about the staggering amount of effort put into making these swords, topped by a striking signature hammered into the blade – one slip and the sword was ruined. However, if you didn’t fork out for the British Museum’s £4.50 audio guide, you’d have walked past the swords without the slightest idea what they were.

It’s always good to see the lives of women represented, especially when it’s not limited to the domestic. We loved the section on sorceresses. These women possessed the gift of prophecy and were feared and respected in equal measure, making their grave goods particularly fascinating. Although the spiritual practices of different Viking settlements varied, there was a widespread belief in shapeshifting. Men turned into bears and wolves, but women’s spirits were allied to more furtive creatures like birds and fish, offering an interesting window into the Viking gender divide.

Near the sorceresses’ wands and finery, there was a tiny statue of a figure wearing female clothing, but labelled as ‘probably’ Odin nonetheless. This made us wonder if (much like female skeletons found buried with weaponry and consequently classified as male) we’re projecting our own gender theory onto history for want of further context. As the Vikings were a largely oral culture, we’ll probably never know.

Speaking of skeletons, bones were displayed sparingly and to great effect. Turning a corner, visitors come across a pile of skeletons divested of their heads – an entire Viking ship’s crew, dumped in a mass grave in Weymouth. The bodies were laid out as they were found, sprawled, face-down, fingers missing, suggesting their hands weren’t tied before execution. We’ve all seen human remains in museums, but this was unusually visceral.

All this was fascinating – if you got close enough. Our major criticism was echoed by everyone we know who’s been to the exhibition: the overcrowding. Many of the smallest and most delicate pieces were by the entrance, creating a bottleneck of bodies. At times it was impossible to see exhibits, and most of the labels were placed below the cases, meaning only the visitors with the sharpest elbows could read them. I’m 6’1″, and I struggled. By the time the room opened up to reveal the breathtakingly gigantic Roskilde 6 ship, most visitors were too stressed to enjoy it.

I love The British Museum, but they should have known better than to cram people in like that. However, if you’re tall or determined, Vikings: Life and Legend is still on until the 22nd of June 2014.

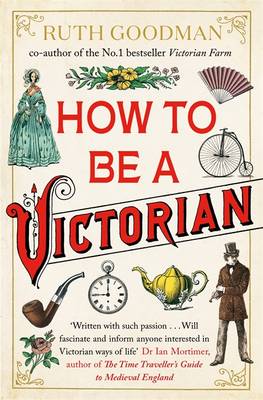

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics. Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises. I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,  He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

I think I was always destined to become that odd woman with a bin bag, scouring roadsides. At least now I’ll have a purpose.

I think I was always destined to become that odd woman with a bin bag, scouring roadsides. At least now I’ll have a purpose.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

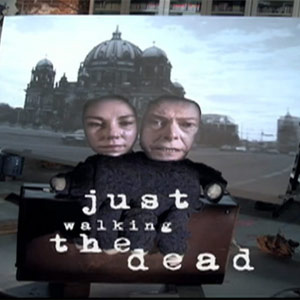

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.