The Heartbeat at My Feet

By now, you’ll have heard the appalling news about the Manchester Dogs’ Home fire. Though the temptation is to detail the circle of Hell I’d dearly love the arsonist to languish in for all eternity, I’d rather focus on the good that can be done for the dogs who survived. Over a million pounds have been donated by the public so far, on top of food, beds, and toys (you can donate here if you haven’t already). All these dogs and more need loving homes, so to prove how fantastic a ‘second-hand’ dog can be, allow me to introduce my rescue dog, Brontë…

I’ve wanted a rescue dog for years. What I didn’t realise was that I’d end up physically doing the rescuing.

A bit of background. My childhood dog, Bobby, was basically my brother. I wrote comics about him, fashioned miniature Bobby adventure novels out of cereal boxes, and set up a fan club. With over fifty members in my Primary school alone, he was possibly the most celebrated Jack Russell in 1990s Suffolk. This was the dog who once leapt out of a window to hijack a Royal Mail van (postman was unharmed) and defiantly trampled the hallowed lawn of Kings College one snowy Christmas Day. He was irreplaceable, but I always knew I wanted another dog after him, especially one who needed a bit of help.

You know that story about how Neil Gaiman found his beautiful white husky by the side of the freeway? This summer was my turn. Driving through the countryside with my dad on a simmering hot day, we had about four seconds to realise a four-legged muddy thing was rocketing towards us out of the heat-haze and that it had no intention of avoiding us. We opened the car door and she threw herself in.

I later joked the sight of her galloping down the tarmac was like the Black Beauty title sequence, but she really was majestic. A long-legged grinning wolf with a foxy tail and black-rimmed yellow topaz eyes.

Up close, it was a different story. She was bony, thirsty, and riddled with fleas. No i.d., just a godawful Paris Hilton-style collar, the leather torn and frayed where she’d been fighting a tether. We later learned she’d been locked in a caravan on one of the hottest days of the year, alone, for hours. Had she not forced her way out, she could well be dead.

Long story short, her owners were happy for us to adopt her. We named her Brontë, because we found her Wuthering.

We bathed her, treated her parasites, got her to eat. It wasn’t an instant transformation. You’d throw a tennis ball and she’d morosely watch it bounce away. She would follow me from room to room, silently, avoiding eye contact. Move too quickly, and she’d flinch. Once, when I left the house, she attempted to squeeze her way out of a first floor window to follow me.

It’s been two months. The vet says she’s almost an ideal weight. She loves to meet strangers and let them tell her what a big, bad, beautiful wolf she is. Toys are no longer a mystery, and she’s beginning to respond favourably to that arcane primate ritual, the hug. And bones. So many delicious bones. We love her. We love our life with her. She’s a troublesome beast, and we wouldn’t be without her.

Adopt a rescue dog. With rescue dogs, you enjoy the satisfaction of taking on a creature who needs your help and seeing it improve day by day as a direct result of your kindness. Adopt a rambunctious terrier. Adopt an old lapdog. Adopt a wee beastie rescued from a puppy-farm cage. If it’s a pup you want, register your interest at your local shelter, and they’ll contact you when a litter comes up. When you adopt a dog from a shelter, you make the choice to take business away from unscrupulous breeders, puppy farmers, illegal importers, and other assorted lowlife. Those people deserve every blow that’s coming to them, and dogs deserve all the very best humans have to give.

“My little dog—a heartbeat at my feet.” – Edith Wharton.

A Sense of Place

I find I’m writing more and more about a sense of place. I’m moving house this week, and all my notes are about waterways, familiar food, and the colour of soil.

I was born on the Rock of Gibraltar. My Dad was stationed at the Navy base there, and I spent the first two years of my life beautifully oblivious to the existence of England and drizzle and Margaret Thatcher. I went back last month, not for the first time. As usual, didn’t want to return.

As a Forces child, going wherever the MOD tells you to while the head of your family sweats in a minesweeper’s engine room somewhere far-off and unpronounceable, you’re left feeling like you belong nowhere. Family interactions take place via satellite phone, friendships are brief, and your birthday plans depend on what Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Miloševic have in store for June. Though I left Gibraltar in the late ’80s, the place always meant more to me than anywhere that followed. Two years after Gib, we were on a godawful submarine base in Scotland. Our allotted house had been arsoned a few months previously. Shards of glass, all over the garden.

The Rock was stable, I was safe there, and it was mine. Nulli Expugnabilis Hosti.

Gib is dusty and colourful and intimate and huge, and every time I get off the plane and crane my neck to see the gulls wheeling around the harsh green crags of the upper Rock, I wonder why I ever let myself get mired in the flat Fens – though I love those, too.

It’s the abundance of light and water.

Plus, you can buy a litre of vodka for £3.99. If that were the case in Britain, you’d be stepping over mounds of poisoned teenagers, but the closest I got to an encounter with a drunk was a sober gentleman carrying an easel, wanting to tell me something important:

“You’ve changed your dress. You were wearing black this morning. I saw you, wearing black. I had a demon inside me for fourteen years. But I met a man from Birmingham, and he made it come out of my neck, like whoosh.”

I find it’s only after you leave a place that you begin to feel it inside you.

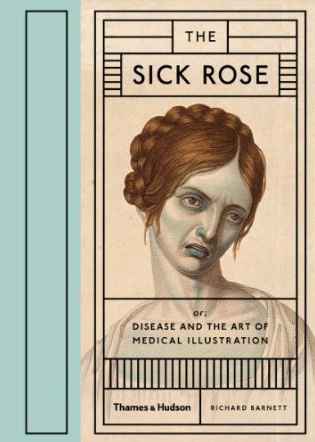

Review: The Sick Rose – Disease and The Art of Medical Illustration

The Sick Rose: Or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration

The Sick Rose: Or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration

Has found out thy bed

– William Blake

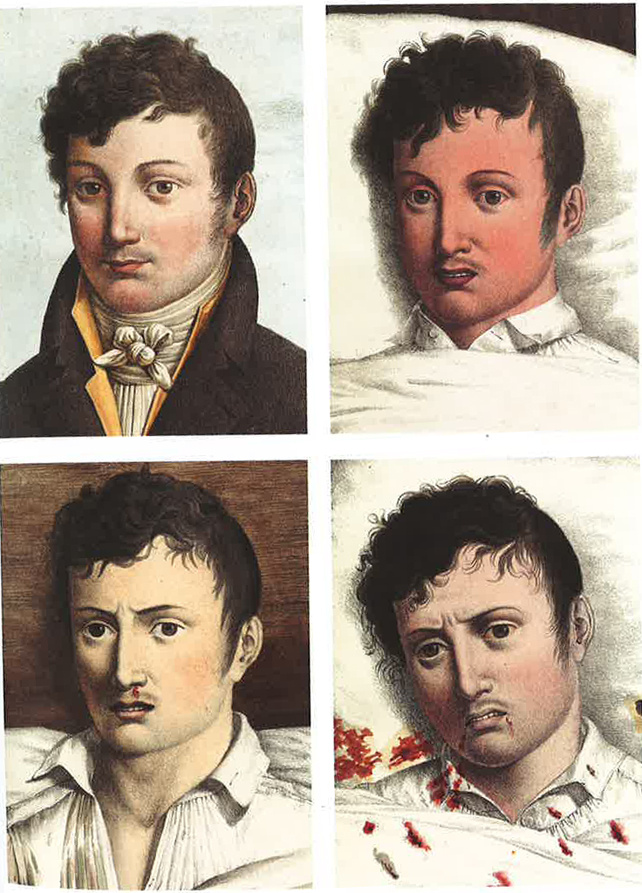

In a pub a few weeks ago, a doctor friend was telling me about his first autopsy. What stayed with him, he said, was how the surface brutality of the act was accompanied by a strange, palpable tenderness as the assembled students protected the face of the deceased, keeping it clean and untouched. I thought of this when reading Dr Richard Barnett’s new book, The Sick Rose, ‘a visual tour through disease in an age before colour photography’. These painstakingly detailed images, so much more intimate than a quick photo session for The Lancet, take on the task of showing human bodies at their most vulnerable while also communicating something of the subject’s soul. Even affirming it, in the face of what was – at least then – helpless suffering.

In case it comes as a shock, I love the history of medicine. Being a) a medical oddity myself, and b) from a family of doctors who refused to censor their conversation at the dinner table, I’m always up for a chat about the experimental origins of rhinoplasty or how best to suspend a foetus in lucite. I’ve been looking forward to this book for months, especially as I went on a London gin tour with Dr Barnett a couple of years ago, and if it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t have known about the 18th century gin-dispensing cat. That’s the kind of thing I need to know.

And have I mentioned the contents of my living room?

I was always going to love The Sick Rose. Physically, it’s gorgeous. A heavy, tactile hardback. Even the endpapers are smallpox, and the clinical, geometric cover design contrasts sharply with a portrait of a wasted young Veronese woman, blue with cholera. Thought has gone into the aesthetic, and it doesn’t go down any of the obvious ghoulish routes, making the reader uneasy from the off. Is this art or science? Is there a line dividing the two?

That’s what I like about the book. It’s unflinching but compassionate. The images of sores, growths, pestilence, and dissection are shocking without being childish. You’re invited to look into these faces and wonder who they belonged to. One particularly moving page features a baby wizened with syphilis, staring past the reader with ancient eyes.

And then there’s the human ingenuity. Silver noses for patients disfigured by venereal disease, or beautiful art nouveau posters warning against ‘the white death’, a poetic and oddly desirable pseudonym for TB. Even my Uncle Thomas Holloway makes an appearance, with his delicate ceramic pots of useless ointment, bearing the image of Britannia and her shield. Disease and death are inseparable from the human condition, so it’s natural we should turn to art for expression and protection.

And then there’s the human ingenuity. Silver noses for patients disfigured by venereal disease, or beautiful art nouveau posters warning against ‘the white death’, a poetic and oddly desirable pseudonym for TB. Even my Uncle Thomas Holloway makes an appearance, with his delicate ceramic pots of useless ointment, bearing the image of Britannia and her shield. Disease and death are inseparable from the human condition, so it’s natural we should turn to art for expression and protection.

These symbolic gestures are not always comforting. For medieval physicians, leprosy was a sign of moral degradation, and the rituals that followed are disturbing. Barnett writes: “[Leprosy was] not only a disease but also a metaphor for the frail state of the human soul, portending the foulness of the grave and the agonies of purgatory. Some Catholic communities developed ceremonies in which lepers were declared symbolically dead, excluded from communal Christian life, even made to lie in a grave while a priest recited a burial mass”.

Compassionate. One can’t help but look at the recent cultural resurgence of zombies and feel queasy. Can such things only appeal to us when we’re comfortably removed from the possibility of actual living death? And what does it say about us?

Philosophical reflections aside, the most unsettling thing I learned while researching The Sick Rose was that the makers of the game series BioShock based the faces of the splicers (drug-crazed mindless killers, if you haven’t played) directly on those of disfigured WW1 servicemen. There’s an essay on it here by Suzannah Biernoff – upsetting reading, and something I’m astonished isn’t more widely known. BioShock is one of my favourite shoot-em-ups, but I’d never made the mental link until Biernoff pointed it out. These ‘points of contact and dissonance’ between art, entertainment, and anatomy too often tread the problematic line of appropriation. It needs examining, and The Sick Rose is refreshingly mindful of this.

In short, I’m recommending the book to everyone. It’s beautiful and emotionally-engaging. All the while the ravages of disease and cultural ideas of monstrosity go hand in hand, thoughtful books like The Sick Rose are still very much needed. It’s natural to be fascinated by the blood and horror of the past, but it’s important to temper that fascination with the humanity of the subject. We mustn’t forget how relatively fortunate we are today.

Review: Vikings at The British Museum

I’m obsessed with History’s drama series, Vikings. I only started watching because I enjoy a bit of the old ultraviolence, but now I’m emotionally involved to an embarrassing degree and spend my time praying for Athelstan’s safety. That poor child has been through enough. All the hacking and slashing has piqued my interest, but, as fans of the show have pointed out, Vikings is only tenuously based on real events. We visited The British Museum’s wildly popular new exhibit – Vikings: Life and Legend – to learn more.

Were the Vikings one gigantic black metal band, or a culture as nuanced and refined as any other? Life and Legend doesn’t try to force you into either camp. What it does do is present the way the Northmen interacted with the cultures they encountered – the Franks, the Slavs, the Anglo-Saxons and beyond – and the evidence isn’t always what most visitors are expecting. Surviving poems prove it wasn’t all about violent conquest:

What’s this talk of going home?

My heart is in Dublin,

And the women of Trondheim won’t see me this autumn.

The girl has not denied me pleasure-visits, I’m glad;

I love the Irish lady as well as my young self.

– Magnus ‘Barelegs’ Olafsson, king of Norway (11th century)

These and other fragments challenge the image of the Viking people as marauding beasts. Sometimes they feel strangely familiar. Take, for instance, this public health announcement:

A man shouldn’t clutch at his cup, but moderately drink his mead.

A thousand years on, and Europe still isn’t listening.

However, if it’s indiscriminate bloodshed you’re after, there’s a lot to take in. We handled a 10th century axe-head, which the attendant helpfully informed us “was for killing people”. Then there was the absolute cutting-edge of weapon technology: Ulfberht swords. So powerfully made and sought-after were Ulfberhts, counterfeits were churned out like dubious Rolexes. There’s a documentary on Youtube about the staggering amount of effort put into making these swords, topped by a striking signature hammered into the blade – one slip and the sword was ruined. However, if you didn’t fork out for the British Museum’s £4.50 audio guide, you’d have walked past the swords without the slightest idea what they were.

It’s always good to see the lives of women represented, especially when it’s not limited to the domestic. We loved the section on sorceresses. These women possessed the gift of prophecy and were feared and respected in equal measure, making their grave goods particularly fascinating. Although the spiritual practices of different Viking settlements varied, there was a widespread belief in shapeshifting. Men turned into bears and wolves, but women’s spirits were allied to more furtive creatures like birds and fish, offering an interesting window into the Viking gender divide.

Near the sorceresses’ wands and finery, there was a tiny statue of a figure wearing female clothing, but labelled as ‘probably’ Odin nonetheless. This made us wonder if (much like female skeletons found buried with weaponry and consequently classified as male) we’re projecting our own gender theory onto history for want of further context. As the Vikings were a largely oral culture, we’ll probably never know.

Speaking of skeletons, bones were displayed sparingly and to great effect. Turning a corner, visitors come across a pile of skeletons divested of their heads – an entire Viking ship’s crew, dumped in a mass grave in Weymouth. The bodies were laid out as they were found, sprawled, face-down, fingers missing, suggesting their hands weren’t tied before execution. We’ve all seen human remains in museums, but this was unusually visceral.

All this was fascinating – if you got close enough. Our major criticism was echoed by everyone we know who’s been to the exhibition: the overcrowding. Many of the smallest and most delicate pieces were by the entrance, creating a bottleneck of bodies. At times it was impossible to see exhibits, and most of the labels were placed below the cases, meaning only the visitors with the sharpest elbows could read them. I’m 6’1″, and I struggled. By the time the room opened up to reveal the breathtakingly gigantic Roskilde 6 ship, most visitors were too stressed to enjoy it.

I love The British Museum, but they should have known better than to cram people in like that. However, if you’re tall or determined, Vikings: Life and Legend is still on until the 22nd of June 2014.

Wunderkammer: Barmy Art has solved all illnesses

While I was finishing my MA, I had a retail job in the centre of Cambridge. The shop no longer exists, thanks to the recession, but it was an exceedingly small space inside a lopsided Tudor building and could usually only house one member of staff at a time. This made it a lonely job, and therefore a magnet for other lonely people who would pop in for a chat about their heroin withdrawals, or try to convert me to Mormonism, or, once, rush in and sob all over the counter about the exam they failed and how their dad back in China was going to murder them.

So I wasn’t too surprised when my boss handed me a sheet of paper with what looked like Hebrew scribbled on it.

“A man came in the other day and pressed this into my hand, saying it was the key to eternal life. I thought ‘that’s Verity’s sort of thing’, so you can have it.”

She said the gentleman in question was tall, well dressed in a tweed suit, with red hair, and left immediately without another word. The key to eternal life, in case you’re interested, is this…

No, I can’t read it either.

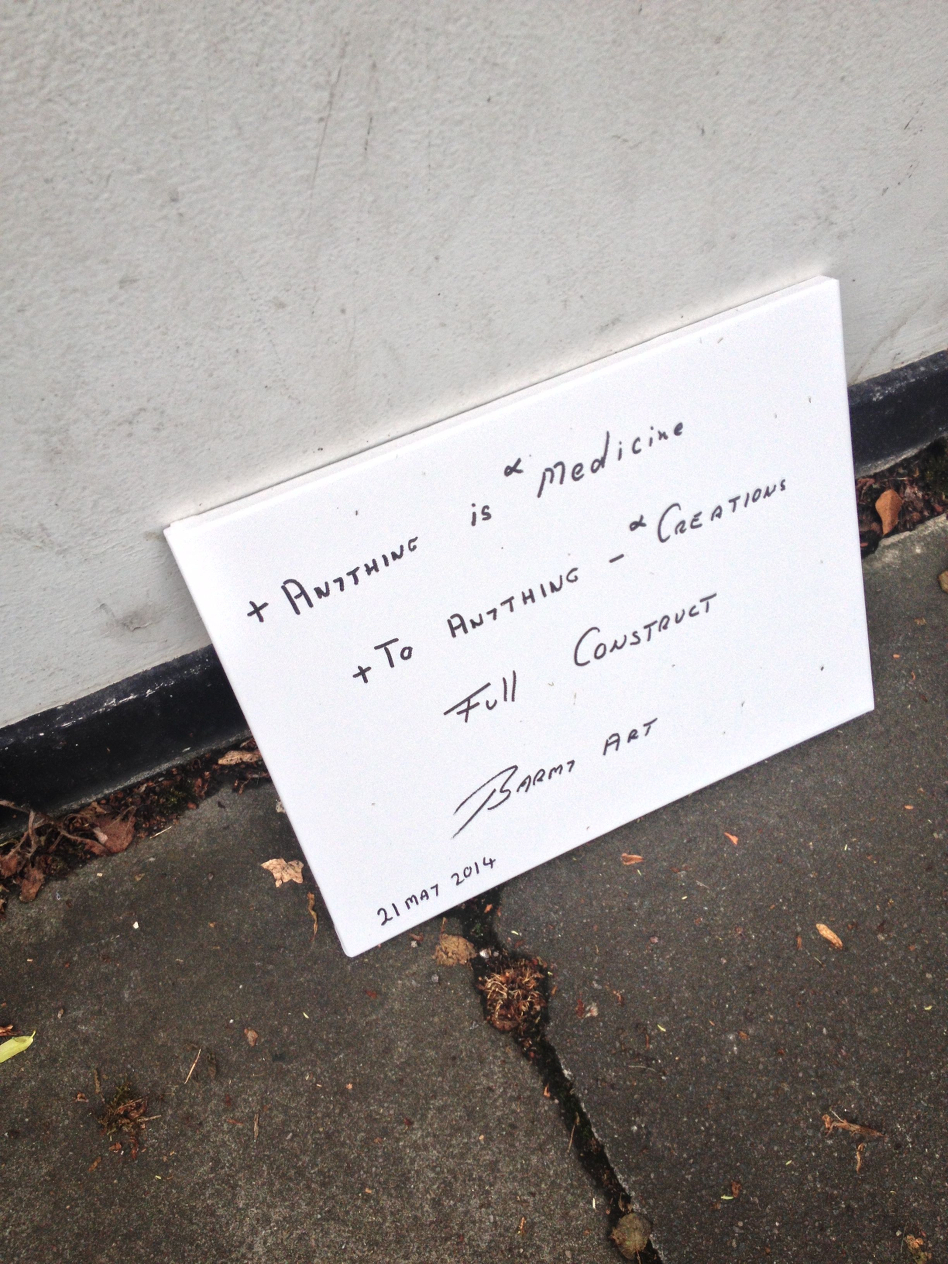

If you’ve lived in Cambridge for a few years, you’ll recognise the handwriting. This is Barmy Art. He’s one of the city’s treasures, along with Man Playing Guitar In The Bin, and Heavy Metal Bicycle Guy. He graffitis what can only be described as profound nonsense, usually mathematical equations or ramblings about the cure for all illness, and, once “Education? You make me laugh”. You can go months without seeing his distinctive black markings, then several crop up all over the place. He’s moved onto canvasses, one of which I found this morning propped against some student accommodation.

He was in the papers a couple of years ago for improving the walls of Jamie Oliver’s restaurant with pi symbols and something about Beethoven, sparking a brief debate about art vs vandalism that probably only made him cackle. If his work at Jamie’s was anything like the five foot long “HAIL HORRORS HAIL” he left on a building site wall in Trinity Street, I commend him.

I like eccentrics, and I hope Barmy Art never vanishes. Allegedly, he was frequently spotted during the ’90s with a packet of Bombay mix strapped to his head, but that sounds a bit rum, even for Cambridge. There’s a Flickr pool dedicated to his delightful weirdness here.

How To Be A Victorian

Ruth Goodman is one of those historians I want to turn up on my doorstep with adoption papers. Brits will know her from her hugely popular television series, Tudor Monastery Farm, Edwardian Farm, and Victorian Pharmacy, where she physically lives the history, coping without heat, going without baths, and stooping for backbreaking farm labour in corset and bonnet.

Her enthusiasm for the daily grind of our ancestors shines through everything she does, from sealing jars with pig’s bladders to grinding up beetles for cure-all pills. Ruth shies away from nothing and reports back with glee. So it’s no surprise that her new book, How To Become a Victorian, stands out among its contemporaries for its sheer physicality and empathy.

My hero

The book takes us through an average Victorian day, from the moment your feet touch the bedroom floor to collapsing in bed after a brutal working day. Or, in the case of the privileged few, dozing off after a 12-course dinner.

Drawing from a wealth of primary material – maids’ diaries, middle class memoirs, and plain old household paperwork – Goodman brings to light some surprising details rarely featured in costume dramas.

For example, would your bedroom kill a canary? Dr Arnott of the Royal Institution thought so.

Ventilation was a big deal to the Victorians. One dubious study stated that a canary, kept in a cage close to the ceiling of the average Victorian bedroom, would die of carbon dioxide poisoning before the night was through. Another claimed it was “madness to sleep in a room without ventilation – it is inhaling poison […] deadly”.

So pervasive was this myth, impoverished parents, wanting the best for their children, would keep the bedroom window open in all weathers, even when blankets were in short supply. It makes you wonder what barmy customs we’re following today for no good reason.

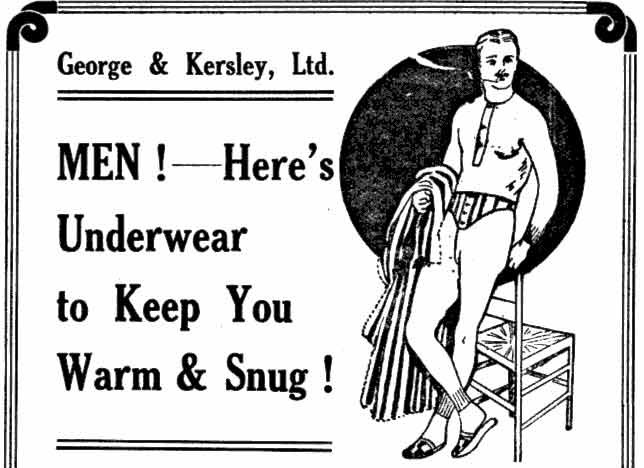

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

Goodman’s other Victorian adventures included setting her petticoats on fire, narrowly avoiding being crushed beneath a startled carthorse, and going without washing her hair for four months. By far my favourite detail was that vodka makes a suitable substitute for laudanum when a recipe calls for it. I think they call that a life-hack.

Unsurprisingly, I loved the book. It’s an invaluable resource for anyone embarking on a historical fiction project. The attention given to the unromantic nitty-gritty of daily Victorian life is much appreciated, and Goodman’s dedication to trying everything, no matter how uncomfortable, dangerous, or potentially infectious, is hugely entertaining for historians, re-enactors and anyone else in danger of death through tight lacing.

Ruth Goodman’s How To Be a Victorian is available now in paperback.

An Easter Brontë Pilgrimage

It’s Charlotte Brontë’s 198th birthday today, and happily I found myself in Yorkshire.

I’ve always been excited to see the land that shaped the Brontës’ imagination; the foundations of Gondal and Angria, and the Parsonage where they lived, worked, and died, particularly as the North is so strikingly different to my own flat East Anglia.

As my Lancastrian boyfriend noted: “That inclining green structure over there… we call that a hill.”

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

Charlotte found the attentions of Sir James and his wife “painful and trying”. The couple tried to coax her down to London for the Season, but Charlotte’s nervousness and dread of being patronised meant she never fully warmed to the couple, despite their real admiration for her radical writing.

The moors further up the country, on the way to Carlisle. Branwell applied for a job as the secretary of a proposed railway line connecting Hebden Bridge to Carlisle in 1845. He was turned down.

The Parsonage at Haworth

With a water supply contaminated by corpses, open sewers, and no ‘night soil’ men to deal with the animal waste in the streets, it’s little wonder that the average life expectancy in Haworth during the Brontës’ lifetimes was just 25.8 years. Nowadays, it’s a pretty little town with a winding road providing a steady influx of tourists. It’s the end of a long rainy winter here, and the heather was flowering and the lambs trotting about in the Easter sunshine. Not remotely Wuthering, but totally lovely.

The Parsonage, from the graveyard.

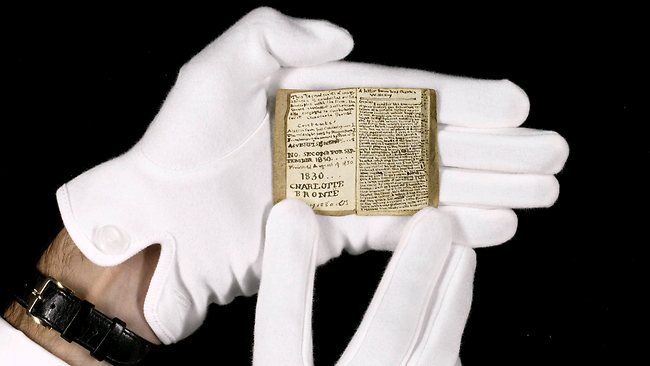

As it was Charlotte’s birthday, we were lucky enough to be invited into the collections room not normally open to the public. There we were shown some of the museum’s treasures, including one of Charlotte and Branwell’s handmade miniature books, so tiny it would fit in the hands of their toy soldiers. There was Branwell’s well-loved copy of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, a small-print volume with no publishing information, suggesting it was a ‘pirate’ copy. Most touching of all was one of the last letters Anne composed before her death, written in a delicate ‘crossed’ pattern to save paper. In it she talks about her desire to survive tuberculosis for the sake of her father, who had already weathered the loss of so many children.

Another of Charlotte’s miniature books sold at auction for £690,850 in 2011.

Excitingly, we also got within breathing distance of a rare first edition of their Brontës’ 1846 collection of poems, published under their androgynous pseudonyms, Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. The sisters paid the publishers’ bills, and sold a mere two copies. So if you’re ever feeling down about your own chapbook, take heart. The copy in the Parsonage collection room was gifted by the sisters to a favourite author, and includes a rather apologetic letter in which they detail its failure to fly off the shelves.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

Charlotte described Emily as “a solitude-loving raven, no gentle dove”, and her presence in the house was less palpable than her sisters’. Emily’s written work demonstrates a self-made inner world fiercely independent from Victorian sentiment and acceptable femininity. Legendary scenes from her life, like her calmly cauterising a dog bite with a hot iron, make her seem remote, but stepping into the windowless kitchen, you get a sense of her there, kneading bread, quietly plotting her next adventure in Gondal.

When Charlotte was 20, she wrote to Robert Southey, Poet Laureate, for career advice. She received one of the blandest misogynist responses on record: ‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life; and it ought not to be […] Farewell Madam!’

Today, on her 198th birthday, when people from all over the world queue to see her writing desk, Charlotte’s reply reads beautifully deadpan:

‘In the evenings, I confess, I do think, but I never trouble any one else with my thoughts.’

Rare Disease Day, the DWP, & ghosts of Girl Guides past

Today is Rare Disease Day, an international day of awareness-raising activities under the slogan “Join Together for Better Care”. Yesterday, the House of Commons held a debate on the effects of welfare cuts on the sick and disabled. As you can see, it was teeming with people who care.

While the debate dribbled on, I read a discussion on one of the Marfan Syndrome social forums. A man was expecting the birth of his son, and wanted to know how he could bring the boy up to see Marfans in a positive – or at least neutral – light. A Marf parent has a 50% chance of passing the mutated gene onto their child. If his son isn’t born with the syndrome, he will still experience the fallout of strangers’ reactions to his father. Which, let me tell you from experience, will not be the stuff gleaming Liberal utopian dreams are made on.

This had me thinking. If I could go back in time to offer my child-self advice on living with disability, what would I say?

Anyone with a rare disease or disorder will be well-acquainted with the word ‘awkward’. It usually arrives wearing a friendly mask: mild teasing when you explain you can’t help your colleague move their heavy desk, or the tutting of your fellow Girl Guides when you faint on the way to the world’s oldest toy shop and have to lie panting on the Oxford Circus floor tiles, watching commuters’ feet hurrying by.

“Hamleys is going to close soon,” someone whined in my ear. “Just stand up.”

Disability is just as much a social challenge as it is physical. You learn you are not simply inconveniencing people – you are the inconvenience.

I grew up before the Internet was permanently glued to the palms of our hands. When I eventually got a modem and an hour each weekend to play on it, it didn’t occur to me to look for advocacy groups, support services, or other people like me. My fear was that I would type ‘Marfans’ into the search field and find nothing but derision and cluelessness, as I had in real life. “If it was really that bad,” my PE teacher said when I tried to explain that trampoline + weak connective tissue = disaster, “I would have heard of it”. Then she made me get on the damn trampoline.

13-year-old Verity internalised the message that disability equals inferiority.

It took me years to gather the courage to seek out other Marfs online. When I did, I realised how valuable support groups are for those of us with rare disorders, and not merely in a fluffy, join-hands-and-sway-to-the-folk-guitar way.

“If you ever get a fuzzy black curtain descending over one side of your vision, drop what you’re doing and run to A&E – your retinas are detaching “ Good to know, yes? Or: “Get a medical alert bracelet. If you’re on the floor with a collapsed lung, you won’t be able to talk.”

Nobody had told me. I was so used to explaining the little I knew about my condition to my own doctors, to being the star attraction for medical students, to fielding gigantic questions from people in power such as the DWP employee who asked, “So, can you just, like, explain to me what this thing is?“. I had been trained to believe that even if quietly soldiering on put me in danger, at least it meant I wasn’t getting in anyone’s way.

The social model of disability says that disability is caused by the way society is organised, rather than by a person’s impairment or difference. When barriers are removed, disabled people can be independent and equal in society, with choice and control over their own lives. – Scope.

Able-bodied or otherwise, we are brought up knowing the archetypes: The Inspiring Cripple, The Grateful Invalid. Strivers and Skivers. The poisonous leftovers of the Victorian Deserving/Undeserving dichotomy. I have said before that to discuss these issues one has to cloak oneself in charm and detachment, because if there’s anything those in favour of welfare cuts can’t stand, it’s the bolshie sick. Perhaps it reminds them of the uncomfortable old adage that a society is only as civilised as its treatment of the vulnerable.

In the UK, it’s a lousy time to be disabled. Vital services are being cut back, benefits are taken away, and women in comas are told they are fit for work. Quota systems deliberately work against us, disturbing documents are leaked, fees stand in the way of employment tribunals, and only a handful of MPs grudgingly turn up to welfare debates. You feel ashamed to seek help; you come to expect disdain. The social model of disability thrives on the active disempowerment of those already at a disadvantage. Watch it at work.

So, on Rare Disease Day, when I like to take stock of my network of support, and the possibilities of the future, I find myself looking at my country and not feeling terribly wanted. Nevertheless, I still have sufficient self-esteem to know that if I could go back and tell my child-self anything, it would be that disability does not equal inferiority. It doesn’t, despite the strenuous efforts of those more fortunate than you: people who may be elected officials, or wearing ATOS lanyards, or just little girls impatient to get to the toy shop before it closes.

Pre-Raphaelite Poetry II

My sonnet ‘Kelmscott’ has been published today in The Pre-Raphaelite Society’s annual poetry competition anthology.

“Collected in this book are the entries to the second Pre-Raphaelite Society Poetry Competition. The poems offer a myriad of pleasantly surprising responses to the Pre-Raphaelites, their successors, paintings, poetry and lives.”

Copies are £3.99 from lulu.com.