A few years ago, I was absorbed in a book at a bus stop when a man materialised in front of me. Grinning, the stranger leant in so close that our noses almost touched.

“Good book?”

It’s fortunate he took me by surprise, because I could well have spoiled his pickup artistry with, “Sure is! It’s about Satan.”

“Follow me, reader! Who told you that there is no true, faithful, eternal love in this world! May the liar’s vile tongue be cut out! Follow me, my reader, and me alone, and I will show you such a love!”

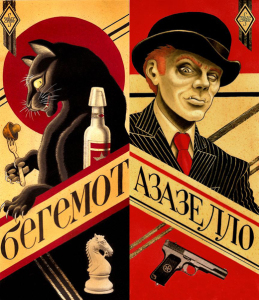

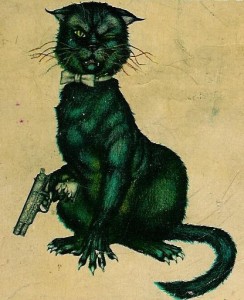

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita is one of those books I thrust at people like a zealot. “No, really. You need this. You. Need. This.” The Devil’s minions – a joker with a pince-nez, a thug, and a wise-cracking, vodka-swilling cat – wreak havoc across 1930s Moscow. If that doesn’t excite you, you’re beyond help.

Now considered a twentieth-century classic, The Master and Margarita was nearly lost to history. A jab at Russian state-sanctioned atheism and the stranglehold of Soviet bureaucracy, the novel is laugh-out-loud-in-public-like-a-lunatic funny, yet heartfelt and romantic, a channel for Bulgakov’s frustration and depression. Juxtaposing his contemporary Russia with Biblical Jerusalem, the story demonstrates Bulgakov’s keen intellect and interest in ethics and questions of personal freedom – all of which could get a writer killed in Stalin’s Russia.

Shortly after kicking a morphine habit in 1919, Mikhail Bulgakov gave up his life as a country doctor to write full-time (just as well, considering he managed to rip out a sizeable chunk of a man’s jaw during a tooth extraction). He enjoyed early success with his plays and short stories before finding his niche, blending merciless political satire with the fantastical. Then, in the 1920s, censorship caught up with him. Stalin personally banned Bulgakov’s play The Run, and the rest of his work, if not banned outright, received brutal criticism for making fun of the Soviet regime.

Surreally, Stalin was a fan of Bulgakov. Allegedly, he saw The White Guard performed 15 times and went so far as to step in and protect him from his harsher critics, claiming dangerous political jargon like ‘counter-revolutionary’ was beneath a writer of such calibre. Bulgakov must have felt in league with the Devil.

The censorship took its toll on Bulgakov’s mental health. As a medical man, he knew he was likely to die young of hereditary kidney disease, and his life’s work was being ‘killed’, as he put it, within his lifetime. In a staggering moment of chutzpah, Bulgakov wrote to Stalin – mad Stalin, Stalin of the Gulags and the purges – demanding to be taken off the blacklist or allowed to leave the Soviet Union. Stalin let him resume his day-job the Art Theatre. But Bulgakov was a watched man, increasingly bitter and depressed. The manuscript he had been working on since the 1920s – the one that would eventually become The Master and Margarita – worried his family and friends. It was an impassioned treatise on artistic and spiritual freedom, and the satire was razor-sharp. Everyone privileged enough to be shown a glimpse loved it, and everyone knew it would never see the light of day.

In a fit of despondency, Bulgakov burned his only draft and was forced to rewrite from memory. This drastic act is one of the autobiographical details that make the story so compelling – in the rewritten novel, The Master burns his magnus opus only to have it returned to him by the Devil. “Didn’t you know that manuscripts don’t burn?”

Bulgakov never saw his masterpiece published. After his death at 49, his wife Elena strove to find a publisher who’d agree to work with such dangerous material. In the end, she could only persuade a small periodical to release the novel in serial form, twenty-six years after the author’s death.

“‘What’s its future?’ you ask?” Bulgakov wrote. “I don’t know. Possibly, you will store the manuscript in one of the drawers, next to my ‘killed’ plays, and occasionally it will be in your thoughts. Then again, you don’t know the future. My own judgement of the book is already made and I think it truly deserves being hidden away in the darkness of some chest…”

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics. Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

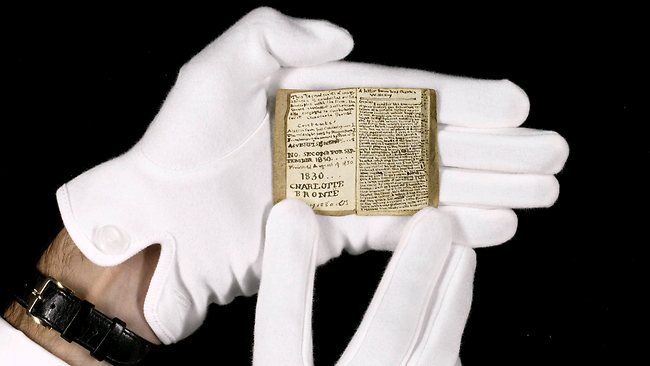

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises. The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,  He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

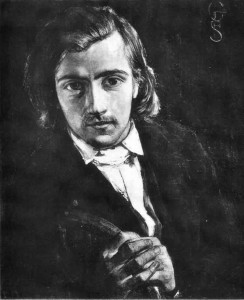

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on

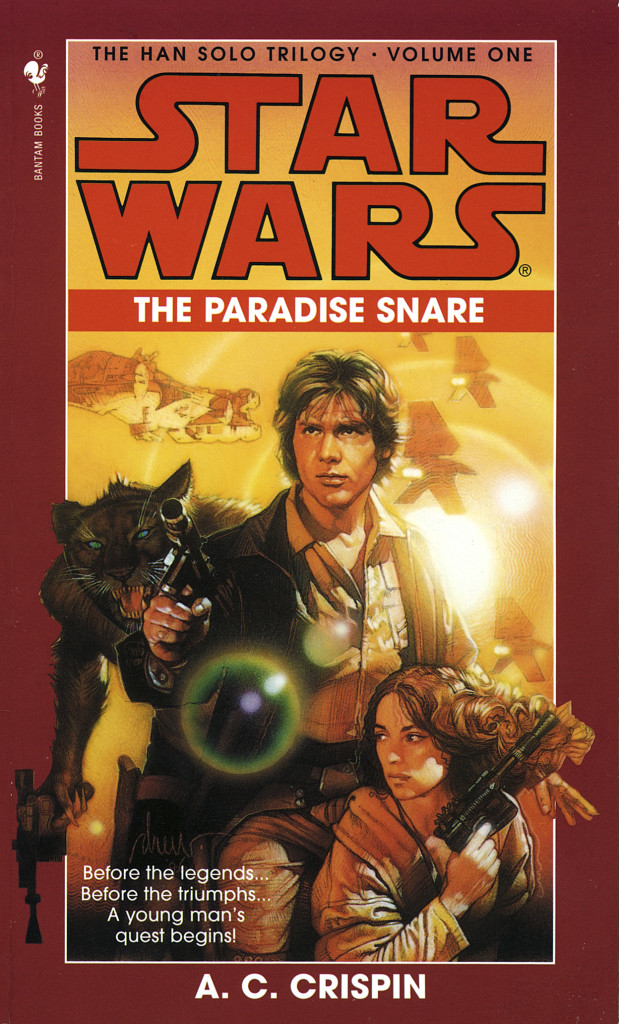

I was a nerdy sci-fi-loving pre-teen when I found The Paradise Snare in – I think – London’s Science Museum, back when a £4.99 paperback presented a considerable investment for your weekly 50p pocket money. A vivid memory: standing on the Circle line, a plastic carrier bag swaying on my wrist, unable to shut this book.

I was a nerdy sci-fi-loving pre-teen when I found The Paradise Snare in – I think – London’s Science Museum, back when a £4.99 paperback presented a considerable investment for your weekly 50p pocket money. A vivid memory: standing on the Circle line, a plastic carrier bag swaying on my wrist, unable to shut this book.