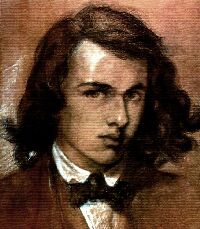

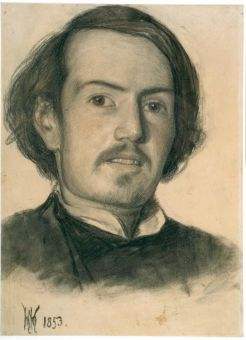

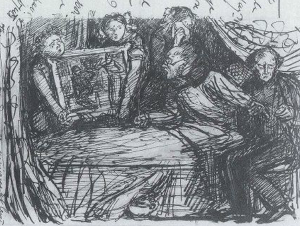

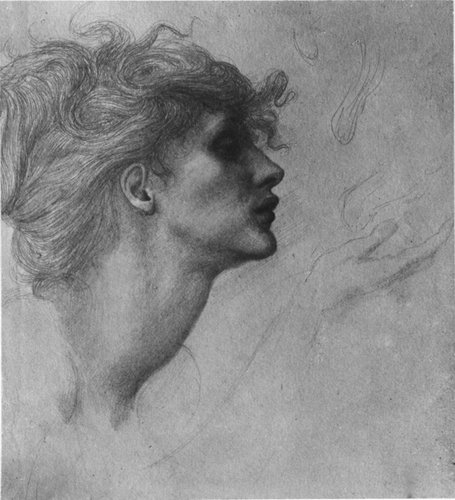

Since I blogged about Walter Howell Deverell’s Twelfth Night, I’ve been wanting to spend a bit more time with the poor doomed boy. So here’s a treat – the study for his ill-fated The Banishment of Hamlet. Dante Gabriel Rossetti was most likely the model for Hamlet.

Walter is mostly remembered as the ‘lost’ Pre-Raphaelite who discovered Lizzie Siddal in a hat shop. Had he accepted full membership into the Brotherhood, he may have been better regarded today, but Walter was the eldest of seven surviving siblings, motherless and later fatherless, too. Linking his name to a controversial gang of artistic upstarts seemed like another way to make life difficult for him and his dependants. As such, he tends to be relegated to a walk-on character in the story of Rossetti’s love-life.

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

Looking like a Victorian Johnny Depp, Walter had a mildly-exaggerated reputation for driving girls to distraction, although his infamous comment about PRB standing for “penis rather better” was probably in reference to the constant pain he would have suffered with the Bright’s Disease that eventually killed him, aged 26. Having had acute pyelonephritis aged 14, I can attest to its utter mind-bending awfulness, which is one of the reasons I feel so sympathetic towards poor old Walter.

The Banishment of Hamlet was doomed from the beginning, receiving a typically venomous Athenaeum review:

Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.

The painting was roundly abused when it appeared at the National Institution in 1851, went unsold, and then, depending on the source, was either blown up in a gas accident or lost in a fire. The study above resides in the Ashmolean under another name, making it difficult to trace.

William Michael Rossetti penned a kinder review*, praising the prince’s moodiness in the same terms he reserved for descriptions of his brother around the same time:

There is a certain brooding indolence in his whole figure; irresolution is shown in the movement of his hand, and mingles even with the settled scorn of his eyes.

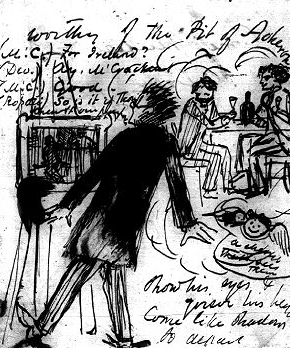

The ‘delinquent school-boy’ attitude of Walter’s Hamlet may well have been inspired by his friend’s air of insouciance; his habit of pulling his sleeves down over his hands and flicking his long fingernails when nervous. The painting certainly seems to have been the subject of jokes between the pair as seen in these cartoons by Rossetti in which the lads’ Irish patron MacCracken erupts with delight at the sight of something that looks an awful lot like Walter’s Hamlet:

‘The long expected Deverell, arriving at length/ find M’C laid up with the sickness of/hope deferred. Owing to an unfortunate error/of packing, the patient is strongly excited on seeing it/and there seems every reason to fear the worst.’ – DGR’s caption

There are lots of these over on The Rossetti Archive, suggesting that Hamlet’s unsaleability was a source of humour rather than anguish. Indeed, Walter exhibited a strange, fatalistic disinterest in the way no one seemed to want his pictures.

I love the way Rossetti always depicts himself as scruffy and round-shouldered next to Deverell’s rather natty figure. Perhaps the ‘delinquent school-boy’ comment appealed to his sense of humour, or perhaps it was a gentle dig at Walter’s popularity with the girls.

It’s a shame that Walter has become a footnote in Rossetti and Siddal’s relationship. There’s a sweetness to his surviving paintings that I find refreshing. Pretty girls pose with pretty birds, and Shakespearean characters totter about in pointy shoes and bright tunics like tableaus from a child’s picturebook. It would be easy to write them off as twee, and perhaps that’s precisely what happened, but I think Walter may have sought out idyllic scenes on purpose, what with the stress of his family responsibilities, the purgatives prescribed for Bright’s Disease, and the eventual realisation that he wasn’t going to make it. His poetry, published in The Germ, betrays a troubled frame of mind:

Though we may brood with keenest subtlety,

Sending our reason forth, like Noah’s dove,

To know why we are here to die, hate, love,

With Hope to lead and help our eyes to see

Through labour daily in dim mystery,

Like those who in dense theatre and hall,

When fire breaks out or weight-strained rafters fall,

Towards some egress struggle doubtfully;

Though we through silent midnight may address

The mind to many a speculative page,

Yearning to solve our wrongs and wretchedness,

Yet duty and wise passiveness are won, —

(So it hath been and is from age to age) —

Though we be blind, by doubting not the sun.

Walter died on the 2nd of February 1854. He only sold one painting in his lifetime.

Rossetti wrote to Ford Madox Brown: “He had been told in the morning that he could not live through the day and he appeared to receive the announcement without emotion or surprise, saying he supposed he was man enough to die”.

It was the first big loss of Rossetti’s life. “I have none left who I love better, and I doubt whether any who loves me so well,” he wrote to Walter’s family. By 1870, he was still trying to sell The Banishment of Hamlet to raise funds for Walter’s surviving family. If he had succeeded, perhaps we would still have it today.

*It has been argued this was DGR writing under WMR’s name, but I’m going to trust the original citation for the time being.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

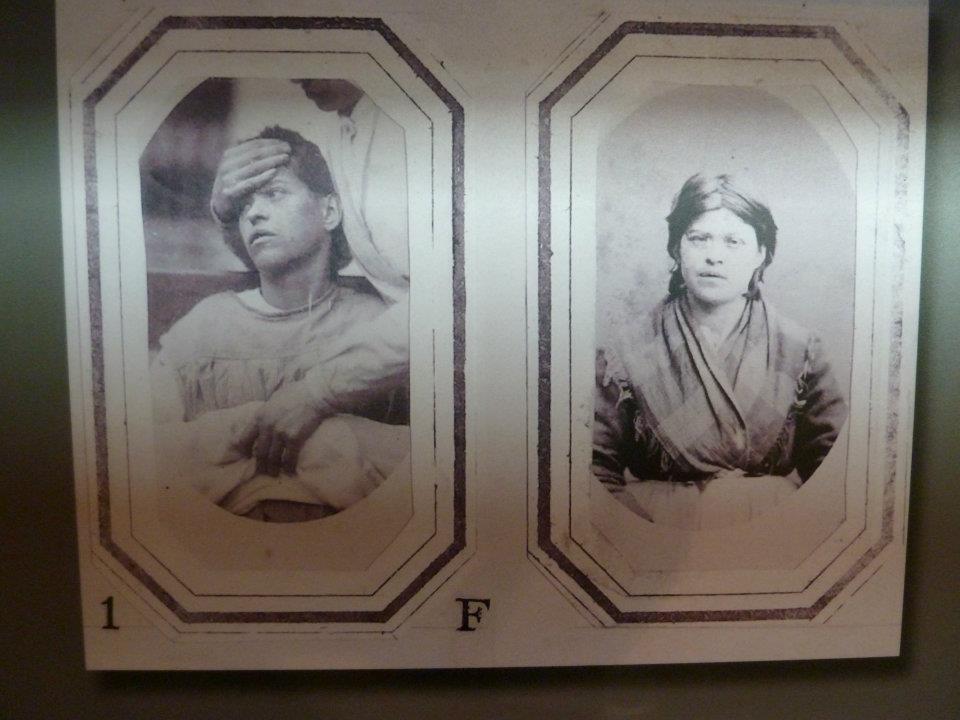

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy. Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence. The certain secret thing he had to tell

The certain secret thing he had to tell