When I was fifteen, I had a summer work experience placement at Ipswich’s psychiatric hospital. St Clements was one of the old ‘asylum’ style hospitals with high-ceilinged wards, green grounds, and a big, romantic entrance hall like something from a smart Edwardian hotel.

When I was fifteen, I had a summer work experience placement at Ipswich’s psychiatric hospital. St Clements was one of the old ‘asylum’ style hospitals with high-ceilinged wards, green grounds, and a big, romantic entrance hall like something from a smart Edwardian hotel.

Among the patients I got to know, there were two shuffling old men who always stuck together. They rarely said a word, even to each other, and spent their days in the potting sheds propagating seeds to sell in the hospital shop. Someone told me these two men had spent their whole lives in the hospital; that their mothers were sent there because they’d given birth out of wedlock. I was sceptical, not because I didn’t believe such awful things had happened, but because I thought that particular social shame was Victorian in origin.

However, one of the many surprising things I learned when we hightailed it to Highgate this week for a talk hosted by Sarah Wise, author of Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England, is that the old story of the dissolute male knocking up the maid and having her put away in a mental hospital to avoid a scandal was in fact a twentieth century phenomenon. And, more surprisingly, Victorian men were more likely to be maliciously accused of insanity than women – because that’s where the money was.

Those who were eccentric, wayward, rebellious, different in some fashion or even just stood in the way (often of money), were often locked up at the behest of family members who stood to benefit. They were aided and abetted by a growing number of ‘mad doctors’ who readily certified ‘madness’. There was money in the lunacy trade — certainly more than in certifying people as sane…

I haven’t yet read the book, but the talk reminded me of when, in Venice this summer, we took the vaporetto out to San Servolo, the so-called ‘island of the mad’ to see the remains of the hospital there. Most of the building is now occupied by the University of Venice, but the pharmacy remains intact, along with a small museum and an imposing white chapel amongst the botanic gardens, radiating heat.

I haven’t yet read the book, but the talk reminded me of when, in Venice this summer, we took the vaporetto out to San Servolo, the so-called ‘island of the mad’ to see the remains of the hospital there. Most of the building is now occupied by the University of Venice, but the pharmacy remains intact, along with a small museum and an imposing white chapel amongst the botanic gardens, radiating heat.

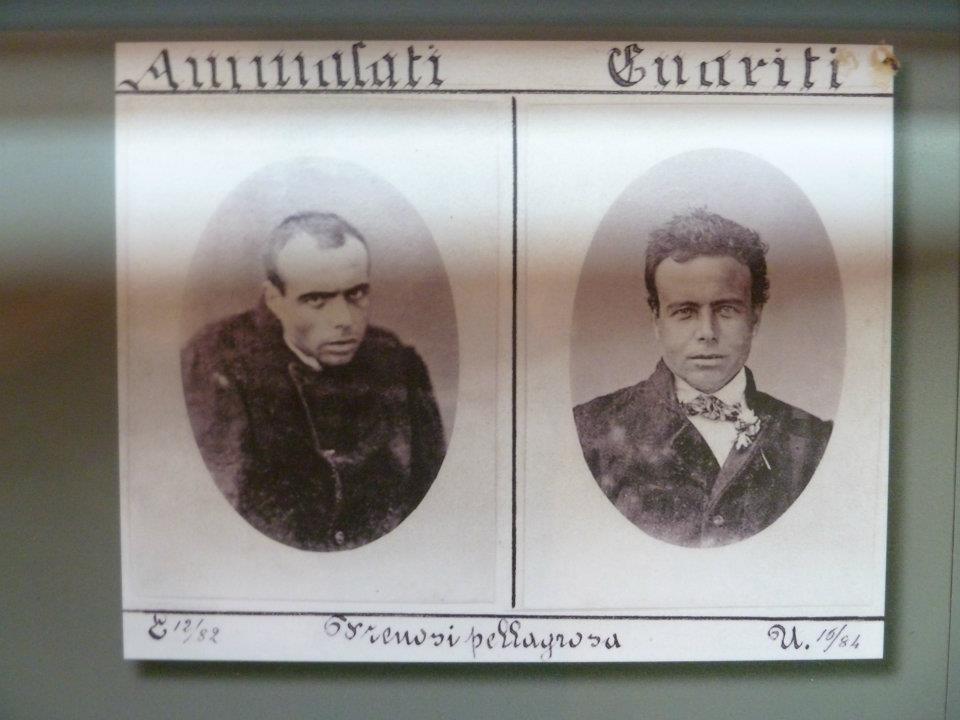

Like the subjects of Sarah Wise’s research, most of the inmates of San Servolo were not mentally ill at all, but dipsomaniacs (alcoholics) or suffering from malnutrition. Being cheap and plentiful, polenta was the dietary staple of the Venetian working classes, but too much of it can cause hallucinations and erratic behaviour. The doctors only realised this when patients who’d come in raving returned to the community – and thus their regular diet – only to be readmitted soon later with the same old symptoms.

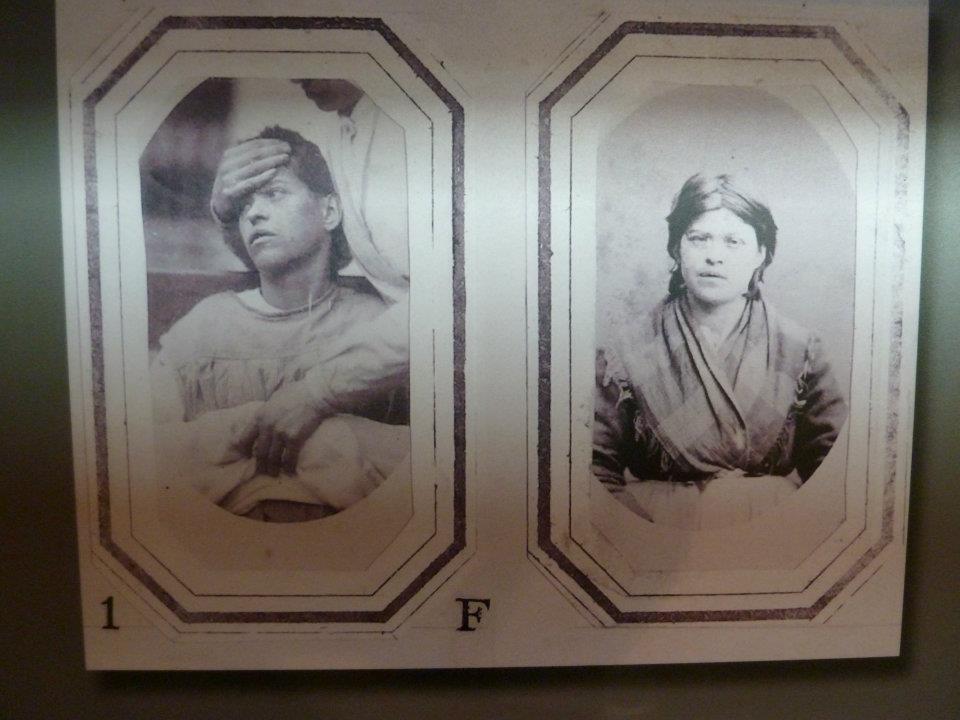

In the museum, there was a long, long line of before-after shots of some of the nineteenth century patients, as if physical appearance can ever really tell us anything.

Having had depression for most of my adult life, there’s always a slightly guilty sense of “there but for the grace of…” when viewing the records of people in similar situations a hundred or so years ago. As Sarah Wise explained, those suspected or accused of mental illness in England were at the mercy of unqualified ‘mad doctors’ and The Commissioners of Lunacy (which sounds like a rubbish steampunk band), a system open to abuse, especially when the theory of monomania drifted across the continent.

Monomaniacs were defined as individuals who appeared fully sane except for one triggering factor, one preoccupation. Monomania was a worrying concept for the public, a) because it was a French theory and therefore probably cobblers, and b) because it made them confront the possibility that mad people looked and behaved just like everyone else.

Which, in my experience, sounds precisely like today’s attitudes.

But doesn’t everyone, healthy or otherwise, have a right to eccentricity? Particularly in England, or so the English tell themselves. And this cognitive dissonance led to some astonishing, uplifting cases of the public turning out in droves to support the accused, even going as far as staging daring rescues. In response to the incarcertion of Lady Lytton — a bona fide case of a disgruntled husband using his influence to silence an intelligent wife — The Somerset Gazette printed in 1858:

Rouse, and assert Old England’s boast

With indignation rife;

From Orkney to The Scilly Isles

Cry ‘Liberty in Life’!

I can’t wait to get stuck into the book. Thank you, Sarah, for an eye-opening talk.

While reaching this article, I was saddened to discover that St Clements, with its vast grounds and grand halls, was turned into a middle class golf resort in 2011. I wonder what happened to those two old men who knew nothing but the asylum.

Great points Verity, that book sounds very good, I love these byways of history.