While I was finishing my MA, I had a retail job in the centre of Cambridge. The shop no longer exists, thanks to the recession, but it was an exceedingly small space inside a lopsided Tudor building and could usually only house one member of staff at a time. This made it a lonely job, and therefore a magnet for other lonely people who would pop in for a chat about their heroin withdrawals, or try to convert me to Mormonism, or, once, rush in and sob all over the counter about the exam they failed and how their dad back in China was going to murder them.

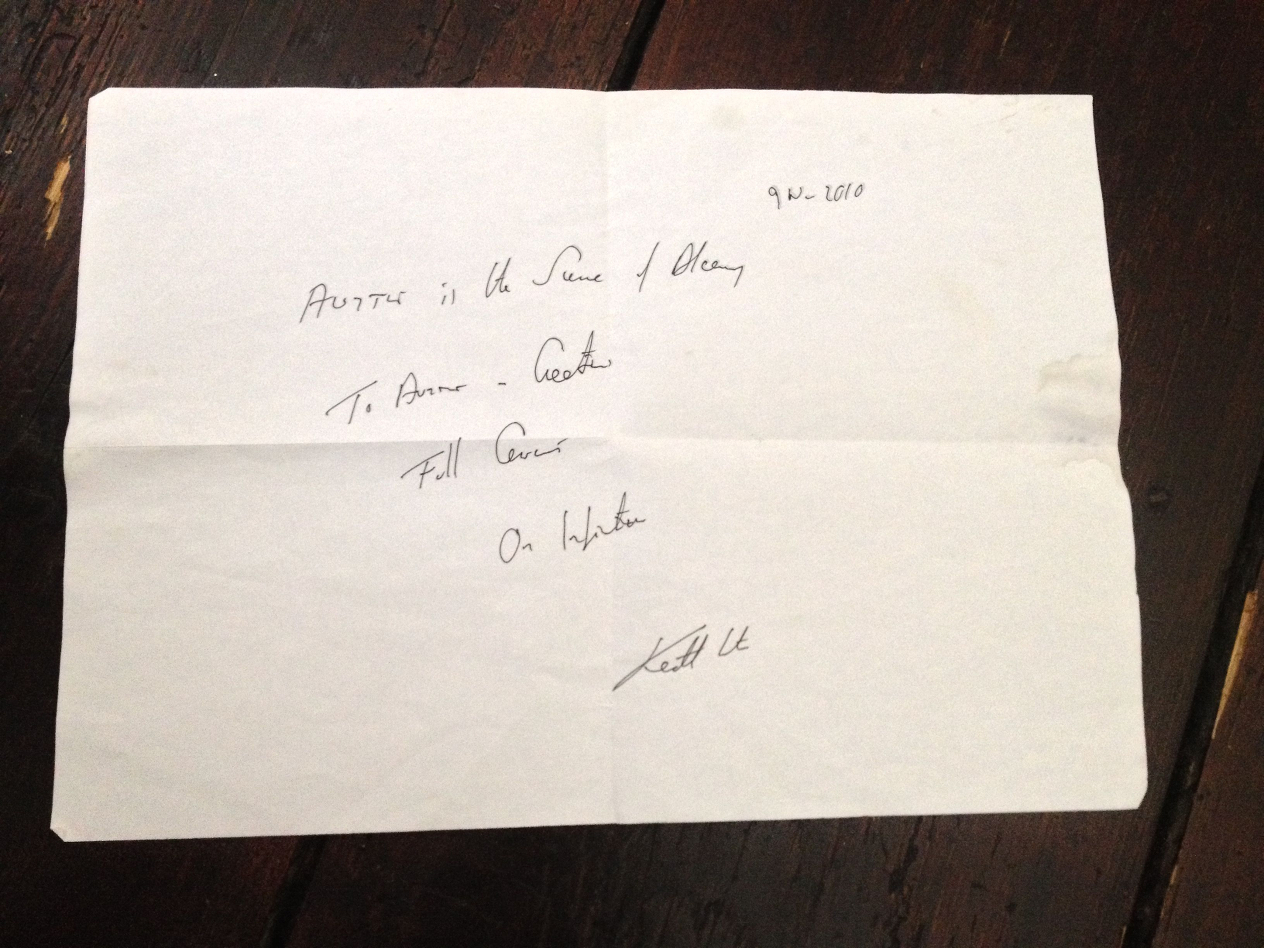

So I wasn’t too surprised when my boss handed me a sheet of paper with what looked like Hebrew scribbled on it.

“A man came in the other day and pressed this into my hand, saying it was the key to eternal life. I thought ‘that’s Verity’s sort of thing’, so you can have it.”

She said the gentleman in question was tall, well dressed in a tweed suit, with red hair, and left immediately without another word. The key to eternal life, in case you’re interested, is this…

No, I can’t read it either.

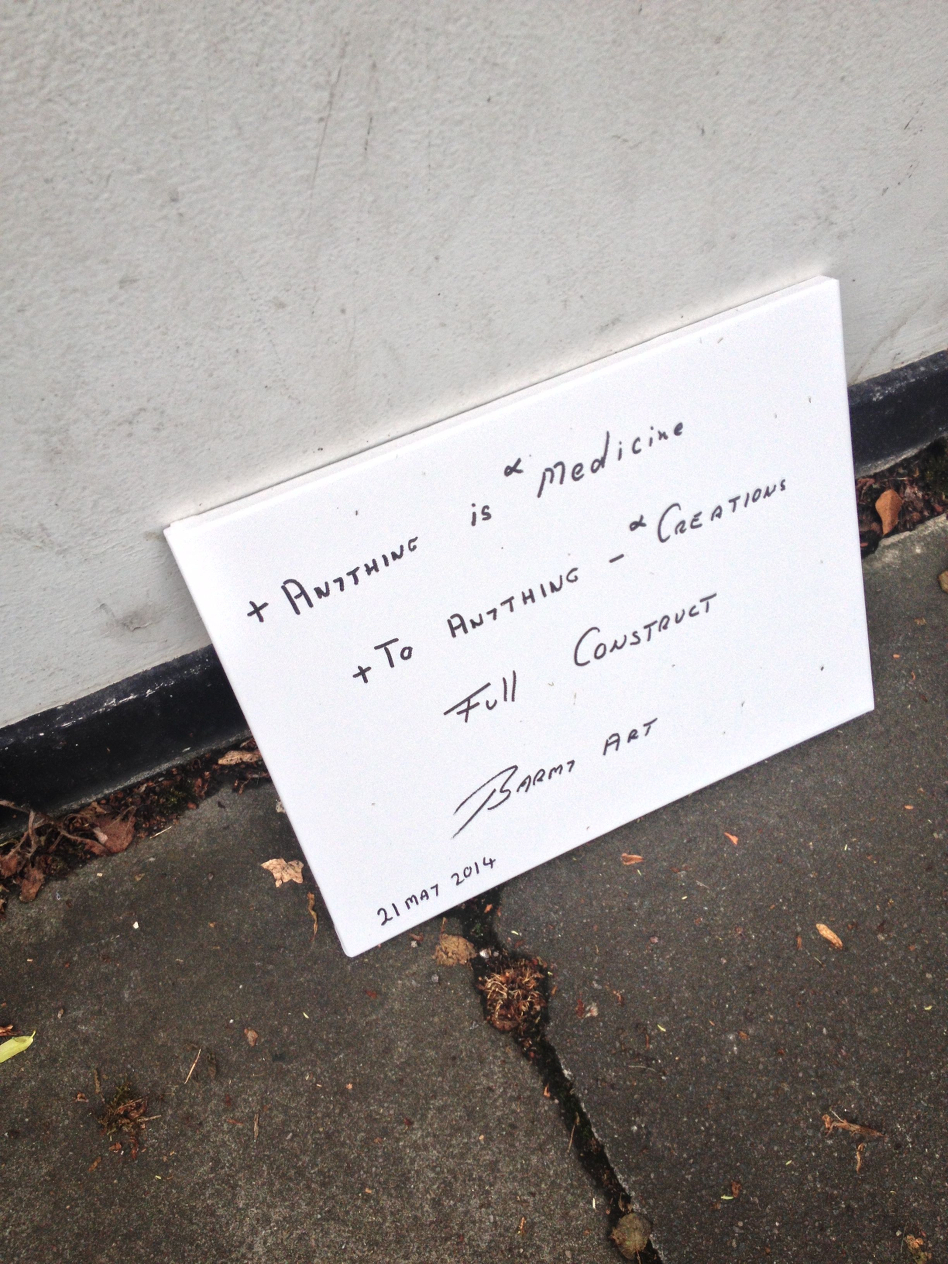

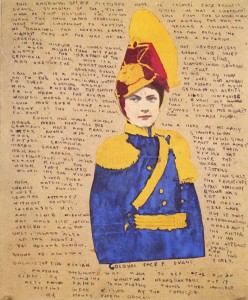

If you’ve lived in Cambridge for a few years, you’ll recognise the handwriting. This is Barmy Art. He’s one of the city’s treasures, along with Man Playing Guitar In The Bin, and Heavy Metal Bicycle Guy. He graffitis what can only be described as profound nonsense, usually mathematical equations or ramblings about the cure for all illness, and, once “Education? You make me laugh”. You can go months without seeing his distinctive black markings, then several crop up all over the place. He’s moved onto canvasses, one of which I found this morning propped against some student accommodation.

He was in the papers a couple of years ago for improving the walls of Jamie Oliver’s restaurant with pi symbols and something about Beethoven, sparking a brief debate about art vs vandalism that probably only made him cackle. If his work at Jamie’s was anything like the five foot long “HAIL HORRORS HAIL” he left on a building site wall in Trinity Street, I commend him.

I like eccentrics, and I hope Barmy Art never vanishes. Allegedly, he was frequently spotted during the ’90s with a packet of Bombay mix strapped to his head, but that sounds a bit rum, even for Cambridge. There’s a Flickr pool dedicated to his delightful weirdness here.

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,  He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

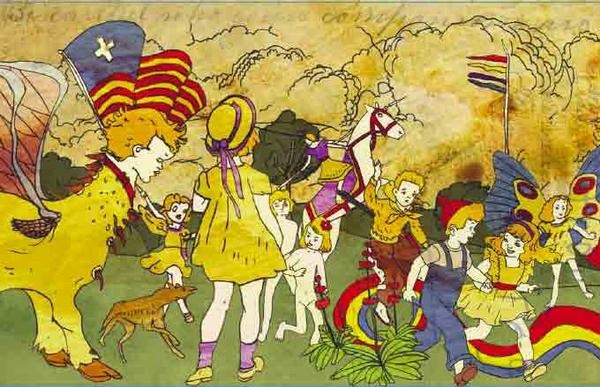

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog. Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

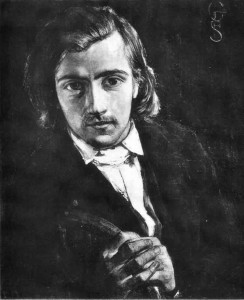

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

![Epitaph for Happiness (and Audrey) There’s not one curse or evil deed, No spells or promises to heed, There is no equal power within the mind Yes! Love’s happiness was hard to find [April, 1969]](http://verityholloway.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/canehillpoem.jpg)

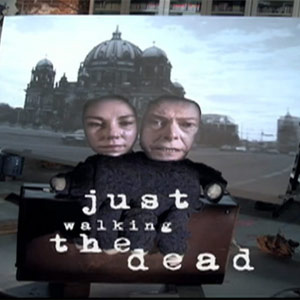

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.