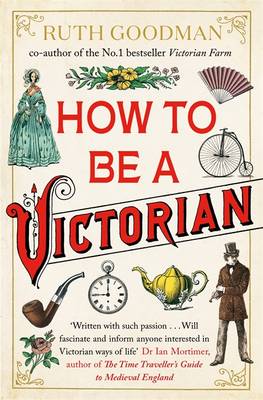

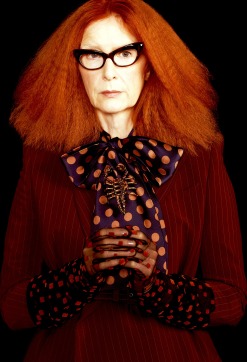

Ruth Goodman is one of those historians I want to turn up on my doorstep with adoption papers. Brits will know her from her hugely popular television series, Tudor Monastery Farm, Edwardian Farm, and Victorian Pharmacy, where she physically lives the history, coping without heat, going without baths, and stooping for backbreaking farm labour in corset and bonnet.

Her enthusiasm for the daily grind of our ancestors shines through everything she does, from sealing jars with pig’s bladders to grinding up beetles for cure-all pills. Ruth shies away from nothing and reports back with glee. So it’s no surprise that her new book, How To Become a Victorian, stands out among its contemporaries for its sheer physicality and empathy.

My hero

The book takes us through an average Victorian day, from the moment your feet touch the bedroom floor to collapsing in bed after a brutal working day. Or, in the case of the privileged few, dozing off after a 12-course dinner.

Drawing from a wealth of primary material – maids’ diaries, middle class memoirs, and plain old household paperwork – Goodman brings to light some surprising details rarely featured in costume dramas.

For example, would your bedroom kill a canary? Dr Arnott of the Royal Institution thought so.

Ventilation was a big deal to the Victorians. One dubious study stated that a canary, kept in a cage close to the ceiling of the average Victorian bedroom, would die of carbon dioxide poisoning before the night was through. Another claimed it was “madness to sleep in a room without ventilation – it is inhaling poison […] deadly”.

So pervasive was this myth, impoverished parents, wanting the best for their children, would keep the bedroom window open in all weathers, even when blankets were in short supply. It makes you wonder what barmy customs we’re following today for no good reason.

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Compare this with the practise of woollen underwear in all weathers. Porous in humidity, insulating in deep cold, a woollen vest and drawers would guard a body from the sudden changes in temperature believed to wreck the constitution. In 1823, Captain Murray of the HMS Valorous returned to Britain after a two-year tour of duty along the freezing Labradorean coast. Each man aboard was given two sets of woollen undies and commanded to keep them on. On his return, Captain Murray was pleased to report he had not lost a single man despite great changes in temperature – this was a record, and one he attributed to wool. For the rest of the nineteenth century, a good set of woollen undies would become recommended by doctors all over the British Empire, even in the Tropics.

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

Naturally, Goodman has tested this advice, along with the long-term use of tight corsets. Lovely to look at, and surprisingly practical for work involving constant bending, Goodman experienced two unpleasant side effects of a tiny waist: 1) Corset rash is worse than chickenpox, and 2) after a time, her core muscles wasted away, giving her a high, breathy voice a Victorian may well have termed feminine and pleasing. She had to retrain her diaphragm with rigorous singing exercises.

Goodman’s other Victorian adventures included setting her petticoats on fire, narrowly avoiding being crushed beneath a startled carthorse, and going without washing her hair for four months. By far my favourite detail was that vodka makes a suitable substitute for laudanum when a recipe calls for it. I think they call that a life-hack.

Unsurprisingly, I loved the book. It’s an invaluable resource for anyone embarking on a historical fiction project. The attention given to the unromantic nitty-gritty of daily Victorian life is much appreciated, and Goodman’s dedication to trying everything, no matter how uncomfortable, dangerous, or potentially infectious, is hugely entertaining for historians, re-enactors and anyone else in danger of death through tight lacing.

Ruth Goodman’s How To Be a Victorian is available now in paperback.

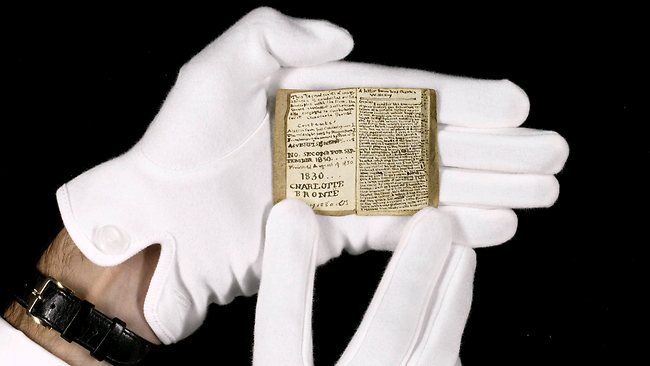

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The previous week, we went to the Jacobean Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire’s Padiham, where Charlotte Brontë paid two awkward visits to Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth in the 1850s. Sir James fancied himself a budding writer, and the green couch where Charlotte withstood her host’s overpowering enthusiasm is still on display.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

The house itself is unexpectedly small. I think that’s a function of decades of Brontë film adaptations set in sprawling Gothic estates, but when you take into account the width of women’s skirts during the 1840s, it’s easy to imagine the family having to shuffle about under each other’s feet, and the emotional closeness such proximity would generate.

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,

I first became aware of Schulz through the Brothers Quay 1986 film of his short story collection,  He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

He is sensitive without being sentimental, as if conscious that the rules of his world are not the same as his neighbours:

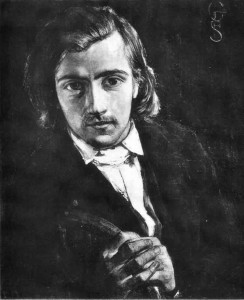

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on