To most who encountered him, Henry Darger was a quiet little man in an army overcoat. He lived alone in a one-room Chicago apartment, attended Mass daily, and swept the floors of the local hospital.

The old man appeared to have no family, no friends, and accepted help only from a select few neighbours who couldn’t agree on how to pronounce his name. But in the early 1970s, when Henry Darger became too frail to care for himself, his astonishing inner world was finally uncovered.

In his tiny apartment, Henry left an autobiography, hundreds of visionary paintings, and perhaps the world’s longest novel – over 15,000 pages. His landlords were astonished, and took the decision to preserve Henry’s room and its extraordinary contents. He is now considered one of the twentieth century’s greatest outsider artists.

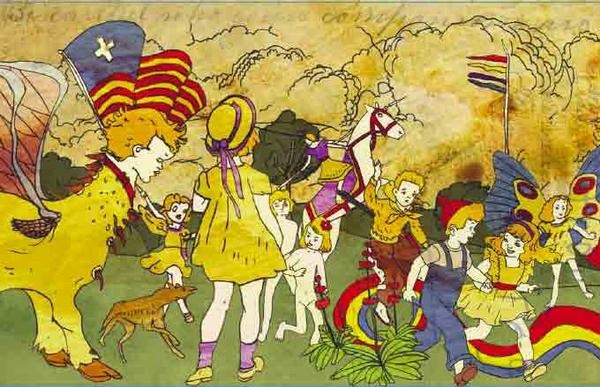

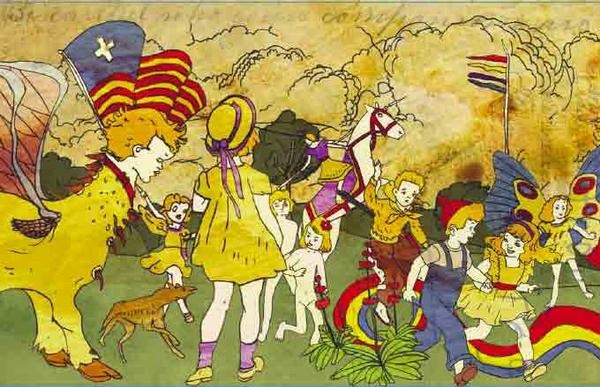

With no artistic training, the reclusive Henry had taught himself how to trace, colour and enlarge the vast collection of ephemera he amassed since the early 1900s, turning sweet Americana into what he called The Realms of The Unreal. Violent, funny, optimistic and fatalistic at once, his is a world in which children live under the constant threat of evil, where little girls are as brave as grown men, and where supernatural creatures live to protect children – and often fail.

So what was Henry like as a child? His story is an unhappy one. Born in 1892, Henry was a socially-awkward little boy, pushed from institution to institution in an age when children with learning disabilities were even more vulnerable than they are today. Orphaned early, he saw how children fared in such environments without a caring adult hand.

“Never had a good Christmas in all my life, nor a good New Year. And now, resenting it, I am very bitter. But, fortunately, not revengeful.”

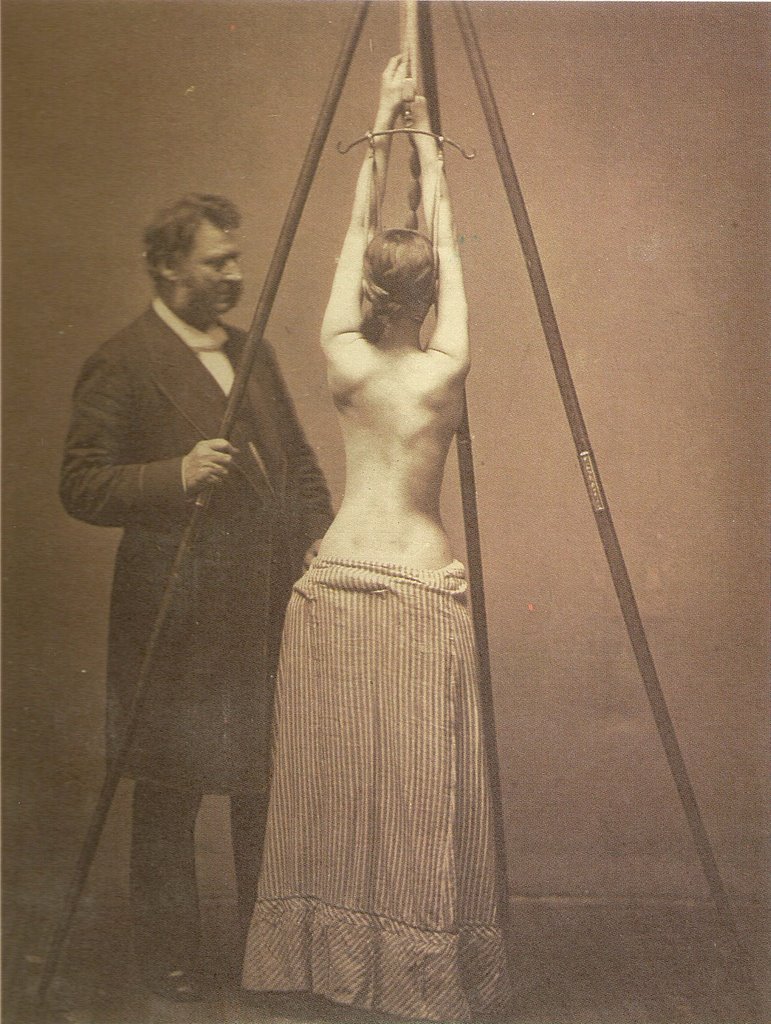

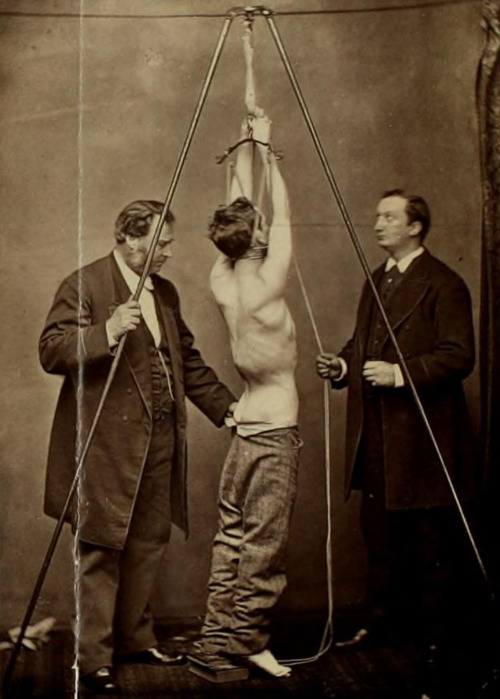

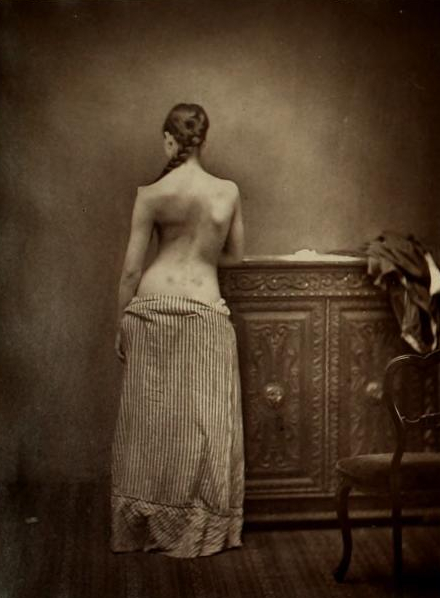

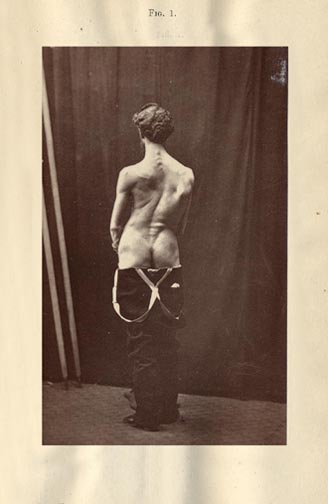

In his autobiography, Henry talks about a time he was lashed by the wrists to the back of a galloping horse as punishment for an escape attempt. Many of his artworks linger on the act of strangulation.

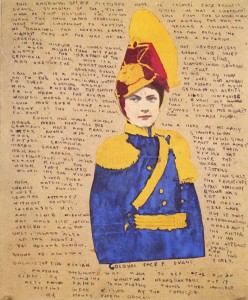

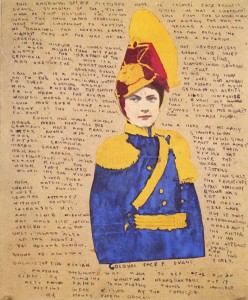

Henry went on to serve in the First World War. Though he never saw active combat, the military experience stayed with him, increasing the vividity of the imaginary conflict he called The Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm between the Christian nation of Abbieannia and the vicious Glandelinians who kidnapped and collected child slaves. In these fictional battles, Henry had the chance to fight back.

“One remarkable incident during the battle when heaven and earth seemed to be going to pieces was the bravery of General Darger. “The cowards! To pursue innocent children with that big number,” snarled Darger in a boiling rage. “I won’t spare a man.” Then he gave the signal to his men to blaze away.”

Henry wrote two endings to his epic: one in which the Abbieannian Christians save the children, and another in which evil triumphs.

In terms of imagination and detail, The Realms of The Unreal reminds me of Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme’s Fourth World, and the Brontë siblings’ Angria and Gondal. Interestingly, these private worlds featured the authors as deus ex machina called ‘genii’. Henry wrote himself into The Realms of The Unreal as the leader of ‘the gemini’, the elite protectors of children.

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

After being taken from his home to the infirmary, the elderly Henry faded fast. His neighbours clubbed together to clean his apartment, whereupon they unearthed a life’s worth of work. No one had suspected the quiet man capable of such far-reaching vision and tenacity. Henry’s reaction to the discovery of his secret world: “Too late now.” He died on April the 13th, 1973.

If you take one thing away from the Henry Darger story, it’s the importance of creation. It doesn’t matter if you can’t draw to prize-winning standard, it doesn’t matter if your spelling is atrocious or you haven’t read the canon of Western literature. If you have something inside you, get it out. Let it flourish on your terms. As Rossetti said, it’s “fundamental brainwork”, not “academic frippery”, that wins in the end.

There is a touching documentary on Henry Darger by Oscar winner Jessica Yu, with music by one of my favourite composers, Jeff Beal. You can currently see the whole thing on Youtube:

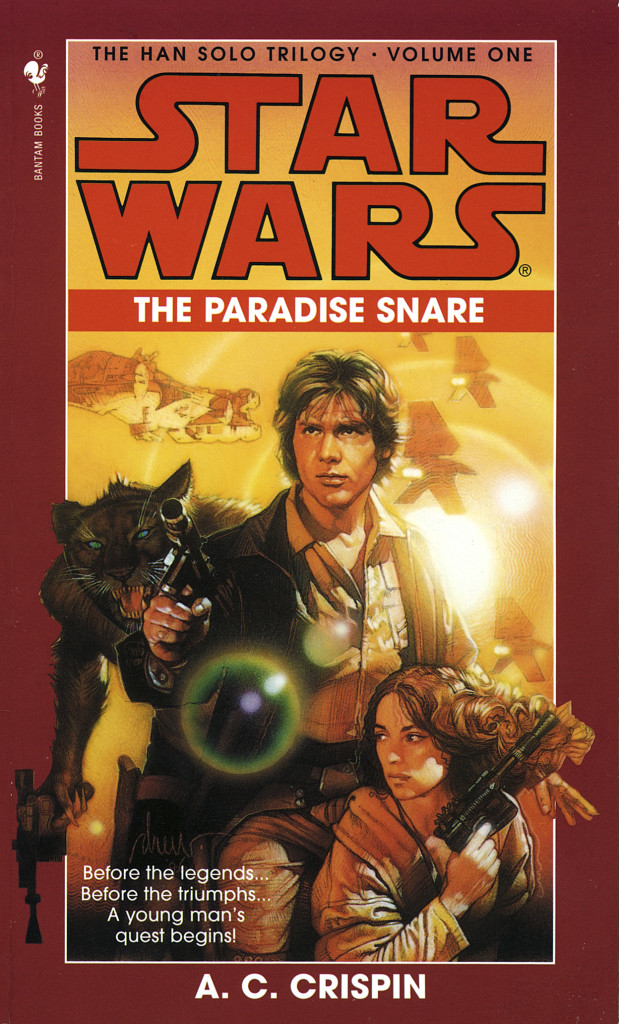

I was a nerdy sci-fi-loving pre-teen when I found The Paradise Snare in – I think – London’s Science Museum, back when a £4.99 paperback presented a considerable investment for your weekly 50p pocket money. A vivid memory: standing on the Circle line, a plastic carrier bag swaying on my wrist, unable to shut this book.

I was a nerdy sci-fi-loving pre-teen when I found The Paradise Snare in – I think – London’s Science Museum, back when a £4.99 paperback presented a considerable investment for your weekly 50p pocket money. A vivid memory: standing on the Circle line, a plastic carrier bag swaying on my wrist, unable to shut this book.

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog.

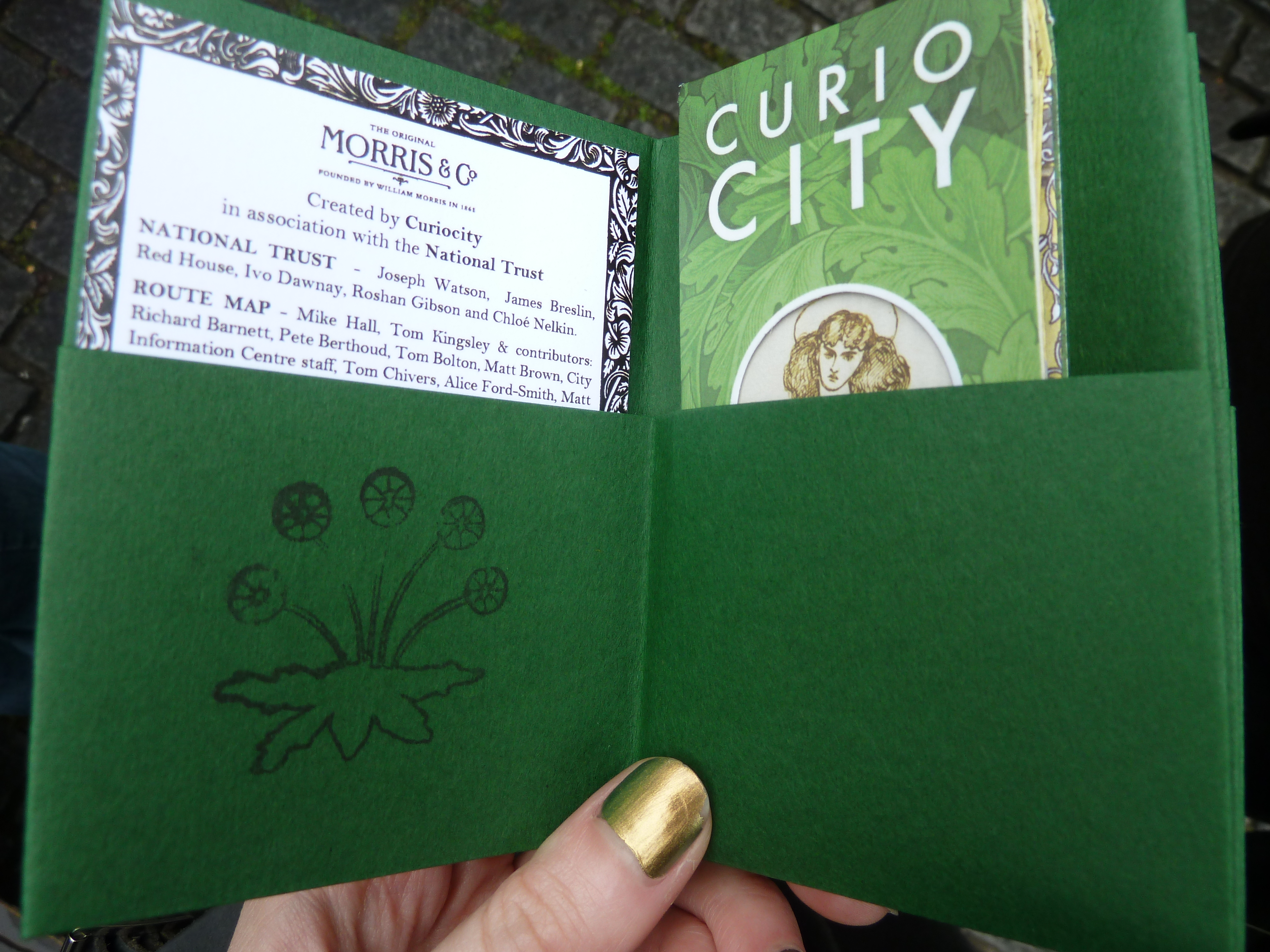

In reality, Henry longed for a child of his own. He petitioned the Catholic church to allow him to adopt, but his request was repeatedly refused. Henry didn’t have the $5 a month it would take to look after a dog. Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

![Epitaph for Happiness (and Audrey) There’s not one curse or evil deed, No spells or promises to heed, There is no equal power within the mind Yes! Love’s happiness was hard to find [April, 1969]](http://verityholloway.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/canehillpoem.jpg)