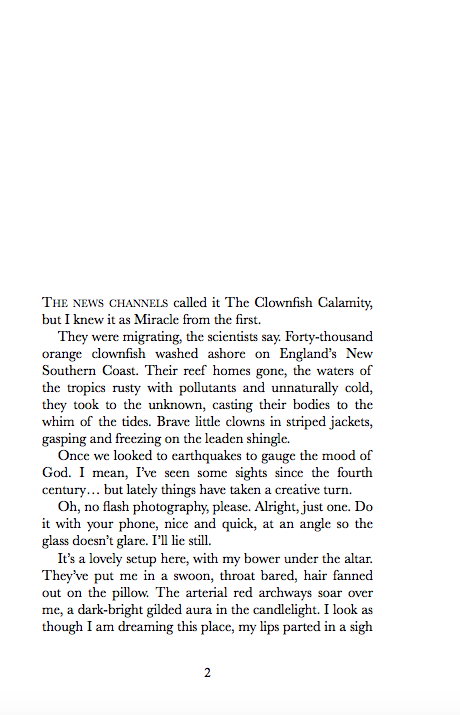

I was in Bury St Edmunds this week, taking a breather from writing The Mighty Healer. I’m immersed in research about Bedlam lately, and there’s only so many times one can read the phrase ‘urine-soaked straw bedding’ before depression sets in. So I thought I’d take a break and return to my comfort zone: hideously brutal martyrdoms.

I photographed this statue of Saint Edmund outside Bury cathedral. In recent years, the interior has been restored to its colourful medieval self, all sky blues and reds and golds, like something a child might paint. The nearby abbey was badly hit during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries – only a few romantic ruins remain – but the site was once a popular pilgrim destination: the shrine of Saint Edmund, martyr king of England.

Edmund was the king of East Anglia during the 9th century. Now the patron saint of wolves, pandemics, and victims of torture, Edmund’s feast day – the 20th of November – marks his death at the hands of Ivar The Boneless during the Viking invasion of England. He is considered by some to be the true patron saint of England. In fact, he was until 1348 when he was officially replaced by St George, presumably because an armour-clad hunk thrusting a spear through a dragon is a more respectable national emblem than a weed with a bowl-cut meekly accepting a beating from a gang of Danes.

Edmund was the king of East Anglia during the 9th century. Now the patron saint of wolves, pandemics, and victims of torture, Edmund’s feast day – the 20th of November – marks his death at the hands of Ivar The Boneless during the Viking invasion of England. He is considered by some to be the true patron saint of England. In fact, he was until 1348 when he was officially replaced by St George, presumably because an armour-clad hunk thrusting a spear through a dragon is a more respectable national emblem than a weed with a bowl-cut meekly accepting a beating from a gang of Danes.

St George being of Greek/Palestinian blood, he doesn’t make an awful lot of sense as Patron saint of England beyond the ‘slaying things is wicked cool’ angle. There’s a campaign to reinstate St Edmund; I met a few of the supporters in 2006, just before Parliament rejected their petition to bring him back. They’re still going, if you’re interested.

After killing Edmund, the Vikings managed to erase almost all contemporary evidence of his reign. We really know very little about the man, but Anglo-Saxons being Anglo-Saxons, we have some nice accounts of his death…

“King Edmund, against whom Ivar advanced, stood inside his hall, and mindful of the Saviour, threw out his weapons. Lo! the impious one then bound Edmund and insulted him ignominiously, and beat him with rods, and afterwards led the devout king to a firm living tree, and tied him there with strong bonds, and beat him with whips. In between the whip lashes, Edmund called out with true belief in the Saviour Christ. Because of his belief, because he called to Christ to aid him, the heathens became furiously angry. They then shot spears at him, as if it was a game, until he was entirely covered with their missiles, like the bristles of a hedgehog (just like St. Sebastian was).

When Ivar the impious pirate saw that the noble king would not forsake Christ, but with resolute faith called after Him, he ordered Edmund beheaded, and the heathens did so. While Edmund still called out to Christ, the heathen dragged the holy man to his death, and with one stroke struck off his head, and his soul journeyed happily to Christ.”

– Ælfric of Eynsham, Old English paraphrase of Abbo of Fleury, ‘Passio Sancti Eadmundi’.

Ivar had Edmund’s severed head thrown into the woods. Edmund’s followers searched for him, calling out “Where are you, friend?” the head answered, “Here, here,” until they found it, clasped gently between a wolf’s paws. The villagers then praised God and the wolf that did His work. It walked tamely beside them before vanishing back into the forest.

Ivar had Edmund’s severed head thrown into the woods. Edmund’s followers searched for him, calling out “Where are you, friend?” the head answered, “Here, here,” until they found it, clasped gently between a wolf’s paws. The villagers then praised God and the wolf that did His work. It walked tamely beside them before vanishing back into the forest.

The 14th century poet John Lydgate called the “precious charboncle of martirs alle”. If you believe Lydgate, Edmund performed dozens of miracles after his death, including setting fire to an uncharitable priest’s house, materialising before the Danish King Sweyn and stabbing him with a spear (because you would, really, wouldn’t you?), and my favourite, catching a Flemish pilgrim in the act of stealing jewels from his shrine whilst pretending to kiss it. Edmund miraculously glued the pilgrim’s lips to the shrine until he apologised.

Right! Back to Bedlam.

“I love it all,” he would say, again and again. “The theatre of life.”

“I love it all,” he would say, again and again. “The theatre of life.”