Happy new year, everyone. I hope it brings you happiness.

Helen Barrell, author of the upcoming Victorian arsenic tome Poison Panic, has interviewed me about Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs, and my 2016 non-fiction book, The Mighty Healer.

Happy new year, everyone. I hope it brings you happiness.

Helen Barrell, author of the upcoming Victorian arsenic tome Poison Panic, has interviewed me about Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs, and my 2016 non-fiction book, The Mighty Healer.

A giveaway for Saturnalia!

Saturnalia was the Ancient Roman mid-December festival of feasting, gift-giving, and wild partying, when ordinary Romans turned social norms upside down and revelled in pandemonium.

Saturnalia features in Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs, my novella of magic, makeup, crypts, and clownfish. I have three signed copies to give away this December, to lend a little pandemonium to your mid-winter festivities.

Giveaway ends December 30, 2015.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

It’s the weekend before the first Sunday of advent, traditionally the time to whip up your Christmas cakes and puddings so they have time to mature (i.e. get sufficiently saturated in alcohol you’ll be comatose until Twelfth Night). In Britain, we make heavy fruitcakes with chopped almonds and candied citrus fruit peel, as well as puddings with a tarry consistency that we like to set on fire. The recipes haven’t changed hugely since the nineteenth century, though we no longer put pennies or tiny dolls in our puddings because, well, death.

It’s the weekend before the first Sunday of advent, traditionally the time to whip up your Christmas cakes and puddings so they have time to mature (i.e. get sufficiently saturated in alcohol you’ll be comatose until Twelfth Night). In Britain, we make heavy fruitcakes with chopped almonds and candied citrus fruit peel, as well as puddings with a tarry consistency that we like to set on fire. The recipes haven’t changed hugely since the nineteenth century, though we no longer put pennies or tiny dolls in our puddings because, well, death.

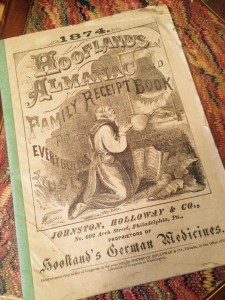

In my research for The Mighty Healer, I got my hands on a gorgeous little household almanac from 1870s Philadelphia. These flimsy books were printed to advertise patent medicines, with calendars, joke pages, and bits of first aid advice inside, so you’d keep it handy and suck up the advertising by osmosis.

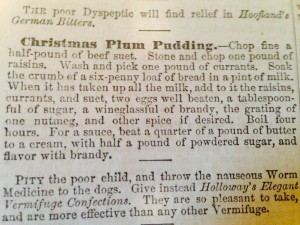

They also contained recipes. Some…more appealing than others. Here are some of the Christmas ones. Try them at your discretion/peril.

I’m not sure I can applaud the juxtaposition of beef suet with vermifuge purgative, but the Victorians did invent Christmas, so who am I to judge…

I’m not sure I can applaud the juxtaposition of beef suet with vermifuge purgative, but the Victorians did invent Christmas, so who am I to judge…

Next up is a more American dish, pumpkin pudding. Just the thing for the pangs of neuralgia.

And finally we have Nun’s Butter and Wine Sauce preceded by Hoofland’s German Bitters, which were good for the appetite, apparently, what with being 25% alcohol.

ADD AS MUCH WINE AS IT CAN TAKE. Nun’s Butter sounds like the brandy butter we put on mince pies to make them palatable. It can also be used as an icing to rescue dry cakes. Trying to dig up the origin of the name, I came across French puff pastries called Nun’s Farts. So there you go. Butter up a Nun’s Fart.

I’m on DeadMaidens.com today, talking about Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs and the first time I met an incorrupt saint.

I was fifteen when I stood over the incorrupt body of Saint Spyridon. It was my first visit to Corfu, a summer holiday with my parents. Peeking out onto a narrow street of lace-makers, icon sellers, and jewellers’ shops, the modest exterior of Spyridon’s shrine made its entrance easy to miss. There was certainly no fanfare for the miracle within as I stepped down into the perfumed candlelight. The Greek Orthodox Jesus possessed a strange allure; stern and penetrating, totally removed from the acoustic-guitar-and-custard-creams Sundays I spent in church at home. It’s heretical to say it, but the shrine had magic. [Read more…]

![]() Baudelaire. I posted this quote on Twitter this morning in response to last night’s terrible violence in Paris.

Baudelaire. I posted this quote on Twitter this morning in response to last night’s terrible violence in Paris.

In times of darkness, art reminds us that humans have always been capable of wonderful things, regardless of war, oppression, or sickness. Sometimes more so for the suffering, if you look at the poems and paintings of the early twentieth century. Art, like heroism, shows its colours more brightly when the world is bleak.

And art can bring people together in strange, synchronistic ways. Now there’s the Internet, people who might never encounter each other in the flesh can link up and enthuse together – something unimaginable just a few decades ago.

The 15th of November is #PRBday, when Pre-Raphaelite devotees raise the group’s profile, shine a light on their legacy, and welcome new friends into the online circle. I’ve met so many fabulous people thanks to these mid-Victorian “boys who couldn’t draw”, as Rossetti called himself and the other PR Brothers.

I was going to write something else today, but none of it seems appropriate. I think what I instinctively want to do is share some hopeful Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

We’ve got art, and we can make more. We’ve got friends, and we can make more of those, too. There’s inspiration in that. There always has been. And where there’s inspiration, life prevails.

Two days until Halloween! Which means there’s still time to acquire some 100% natural dark circles around your eyes. Maybe she’s born with it; maybe she’s too scared to sleep. I’ve been meaning to do a book recommendation post for a while, so here are some scary stories to give your cheeks that desirable rosy glow. White roses. Dead ones.

Susan Hill is one of our finest living ghost story writers, and Dolly is the tale of what happens when children go bad. Brief enough to be read in one sitting, Dolly takes the old spooky doll trope and shakes it by the shoulders.

I love Peter Ackroyd. I love hulking London churches. And I love a nice occult murder conspiracy. Ackroyd has a way of presenting jump-scare moments so coolly, the reader is totally taken by surprise. He’s still one of the few horror-esque authors who can genuinely thrill me.

Photographs of abandoned Arctic whaling stations are terrifying, let alone having to live in one, alone, when you know the sun isn’t coming up for months. Part paranormal horror, part solitude survival story, Dark Matter is a genuinely refreshing, tense book with a vivid sense of place.

A Good and Happy Child

We were all lonely children, right? And we all wished for a friend. George Davies lived to wish he never had.

The Quick

The Quick is for vampire lovers. ‘Enter the rooms of London’s mysterious Aegolius Club – a society of the richest, most powerful men in England’. I want more from The Quick’s universe – it feels a natural springboard for short stories and sequels.

The Haunting of Hill House

“No live organism can continue to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality”. Shirley Jackson is the master of the haunted house story. It’s a classic. Go and read it.

Have a pleasurably traumatic happy Halloween, friends! And recommend me some books in the comments.

I know, too early for snow. But my short, nasty, and very cold story, The Frost of Heaven, will be included in Fox Spirit Books’ Winter Tales anthology coming early next year. Fox Spirit won Best Independent Press at the British Fantasy Awards today. Well done, guys!

This post is brought to you by a cocktail of painkillers, hypnotics, and anxiolytics, administered by a lovely NHS anaesthetist whose name I can’t remember – only the sight of her leaning over me with a smile: “You’re going to forget my name.”

Just some routine Marfans stuff. But two days later, I’m still swimming through dreams. I like to think the lingering hypnotics are giving me the authentic Rossetti experience, minus the raccoon hiding in the wardrobe. And the genius.

Hanging onto the tail of this wooziness, I want to talk about childhood, but also about Jan Švankmajer’s gorgeously surreal 1988 film, Alice: “A film for children… perhaps.”

Years ago, a counsellor complimented my socks. They were pale blue and white striped, up to the knee, and they were perfect, she said, “because you’re Alice in Wonderland.”

This probably wasn’t wise of her.

Like a lot of only children travelling with military parents, I was prone to dissociation. That’s the psychology term for intense daydreaming. And I mean intense – to the point that reality was almost entirely blocked out for the majority of every waking day. Mostly, it was paradise, but there were snags. Teachers found they had to full-on yell to catch my attention. I once kicked a cannonball-sized hole through a porter cabin wall without noticing.

Dissociation is a creative coping mechanism for when life is unstable or lonely. It’s very much like the intravenous sedative experience – a protective measure that picks you up and whisks you away. Eventually, children who habitually dissociate grow up to remember more about their dream worlds than the reality of the past. Some of them become writers. Ahem.

Onto Alice. As a chronically fantastical child, I was rankled by the Disney version of Alice In Wonderland. It was all so very pastel, so very clean. Nothing pristine, I knew, could ever be magical. Childhood is frightening, and nonsensical, and inappropriately hilarious – much like the original Wonderland tales.

Children inhabit another planet. Lewis Carol knew that.

So on the other hand, you have Jan Švankmajer’s Alice. A film for children… but probably not for parents. The White Rabbit is taxidermy, leaking sawdust. Socks have teeth and the jam is full of drawing pins. Wonderland itself is a wreck of broken china and splinters, pickled specimens, potted tongue (prone to slithering), and other Victorian relics. Alice – the only living person in the film – has a way of turning into a decidedly spooky china doll and back again, tearing off the chrysalis of painted skin and making a run for it. Like the doll, her facial expression never changes. She never smiles or frowns. Those are things you do for others, and this Alice is content to be alone with her imagination.

Drowsy and doped as I am, it strikes me how strangely authentic Švankmajer’s vision of childhood imagination was.

In 1989, the year after Švankmajer released Alice, I was three. The Navy posted Dad to Scotland, and we ended up living on a dismal estate near a submarine base. Someone had spray-painted a peace symbol on the garden fence for our arrival. I wasn’t ready for school, and we never stayed anywhere long enough to make friends. I think I tried, on a few sparse occasions, but it was so much effort for so little return when inside was infinitely better than outside.

Perhaps it was the jerky stop-motion animation, or the twisted quality – lurking on the indistinct border between dreams and nightmares – but watching Švankmajer’s Alice for the first time a few weeks ago, I began to spontaneously remember scraps of day-to-day surrealism from that time in Scotland.

Someone – I forget who – told me bubbles were living things, and that when you popped them, they died.

There was a nearby play park where a boy knocked himself out trying to make the swings turn full circle. I saw his body in a red tracksuit, face down on the ground. ‘Cracked his head open’, I thought for years, was literal. Bash the hinge hard enough and the skull pops open like a spring-loaded box.

That play park was an island of concrete amongst hillocks of unkempt greenery. One day, some other children took my doll, so I wandered off to where you could see the Forth Rail Bridge, muddy-bloody coloured, in the distance. Over a hill, I found the skull of a ram, picked clean. The coiled horns looked like the fossils in my dinosaur books. I can’t recall the doll.

From the spare bedroom, if the light was good (by Scottish standards), you could see dark cylinders moving slowly through the cold seawater. I’ve never grown out of the fear of submarines, but the house held hidden dangers of its own. I was playing in the garden. Making a pile of gravel. The house had been arsoned before we moved in, so the gutters full of gravel also contained all the glass from the shattered windows. Not that I noticed. I was grabbing handfuls, piling it up, until I registered I was bleeding from dozens of tiny cuts. I took myself up to my parents’ bedroom and triumphantly held out my hands to them. It didn’t hurt.

A fisherman on a jetty shouted at me for dropping a stone in the sea and disturbing the fish.

“I want to cut him in half,” I said, and I can still clearly see the satisfying image in my mind, of a man sliced in two like a pink salmon.

Sugar, spice, and murder fantasies. There’s a whimsical grotesquery to childhood I think we’re programmed to erase. Perhaps it’s only free to come out when we’ve been dosed up by friendly anaesthetists without names.

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.