Photo by Karen Sheard on Flickr

The Watchmaker’s Gift

I returned from midnight Mass eager for the warmth of my master’s hearth and something indulgent to drink. I had enjoyed the Christmas service, on the whole, but I was saddened my master was too unwell to accompany me as he had for many years. I was a small boy when he selected me as an apprentice, appreciating the slender dexterity of my fingers, naturally suited to the intricate arts of the watchmaker. Since then, his astounding miniature creations had earned us both considerable fame – timepieces no bigger than buttons, working clocks for dolls’ houses, and even a jewelled ring that chimed on the hour and was rumoured to have been purchased for a Russian princess. With his advancing age, my master’s mounting obsession to create the tiniest watch imaginable had claimed his eyesight. Now, even with his thick spectacles, he struggled to see so much as his own knife and fork when I served him supper. It pained him, and at church that Christmas Eve I said a prayer to all the saints I knew:

“Return my master’s sight to him, even just for the night. Help him craft one more tiny, wondrous thing.”

When I returned to our home above the workshop, I found only one candle lit beside our diminutive Christmas tree. My master sat in the gloom. I could barely ascertain the glint of his spectacles. The dark was bad for his eyes and the cold bad for his chest, but I hadn’t the heart to scold him, particularly when I noticed, next to the tree, an enormous box. It was wrapped in red paper and sealed with a ribbon of gold, and was almost as tall as me. It had not been there when I left.

“A small token, dear boy,” I heard my master say, from the shadows. “Unwrap it, please. It is past midnight, after all.”

With a glimmer of childish pleasure, I set about opening my gift. As I tore through the red paper, thinking I would find some large wooden chest or armchair, I was surprised to find neither of these things, but another layer of wrapping.

“Smaller,” he chuckled. I smiled, heartened by the return of my master’s good humour, and continued to unwrap my gift. Yet I found only another layer of paper.

“Smaller,” said my master.

After some time and much bemusement, I was surrounded by mounds of discarded red paper. The package had shrunk to the size of a shoebox, but I was no closer to my gift.

“This must have taken you hours to wrap,” I laughed. How had he hidden something so large from me? Our workshop was modest, our rooms above intimate. I knew of no-one with sufficient humour to help him in such a task. I was the only family the old man had.

“Smaller,” my master coaxed from the darkness.

Dawn approached. My head swam with my need to sleep, and the gift, still neatly wrapped, was now small enough to hold in my palm. I was irritated with him, and annoyed at my own pettiness in the face of such an elaborate and no doubt well-intentioned joke, but still I tore through layer upon layer of paper and ribbon. My fingertips grew sore. My eyes ached with the lack of light, and for another hour the only sounds in the room were the tearing of paper and the soft, infuriating laughter of my master.

“Smaller.”

When the gift was the size of my thumbnail, I thought that surely, at last, I was close. It would be one of his miniature timepieces, the smallest yet, a wonder of the age. My prayer would have been answered. We would share a brandy and chuckle at my astonishment, and in the light of Christmas Morning we would eat fruitcake and play cards as we had together since I was a boy.

Yet as I peeled back the final layer of paper, no bigger than a postage stamp, I found the package to contain nothing.

At first, I simply stared. My hands shook. There was no miniature timepiece, no gift, not even so much as a grain of rice for my labours. And my master, not a cruel man, not a man given to spiteful gestures, was laughing in his chair, in the corner, in the darkness. Laughing at me.

I snatched up the candlestick and strode with it to his chair to demand an explanation, to touch his brow for signs of sickness, or worse, some brain fever brought on by frustration and old age. I lifted the candle above my head to better view him and was about to open my mouth, unable to contain my annoyance any longer.

He had, for some considerable time, been dead.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

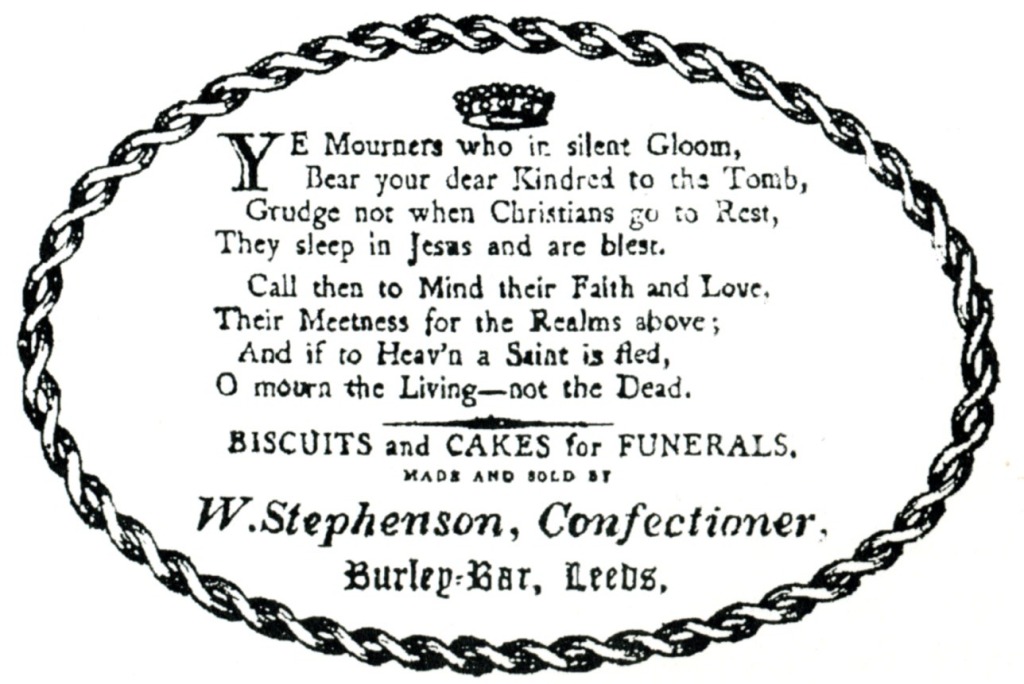

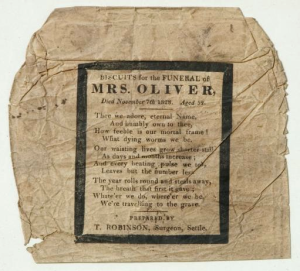

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on