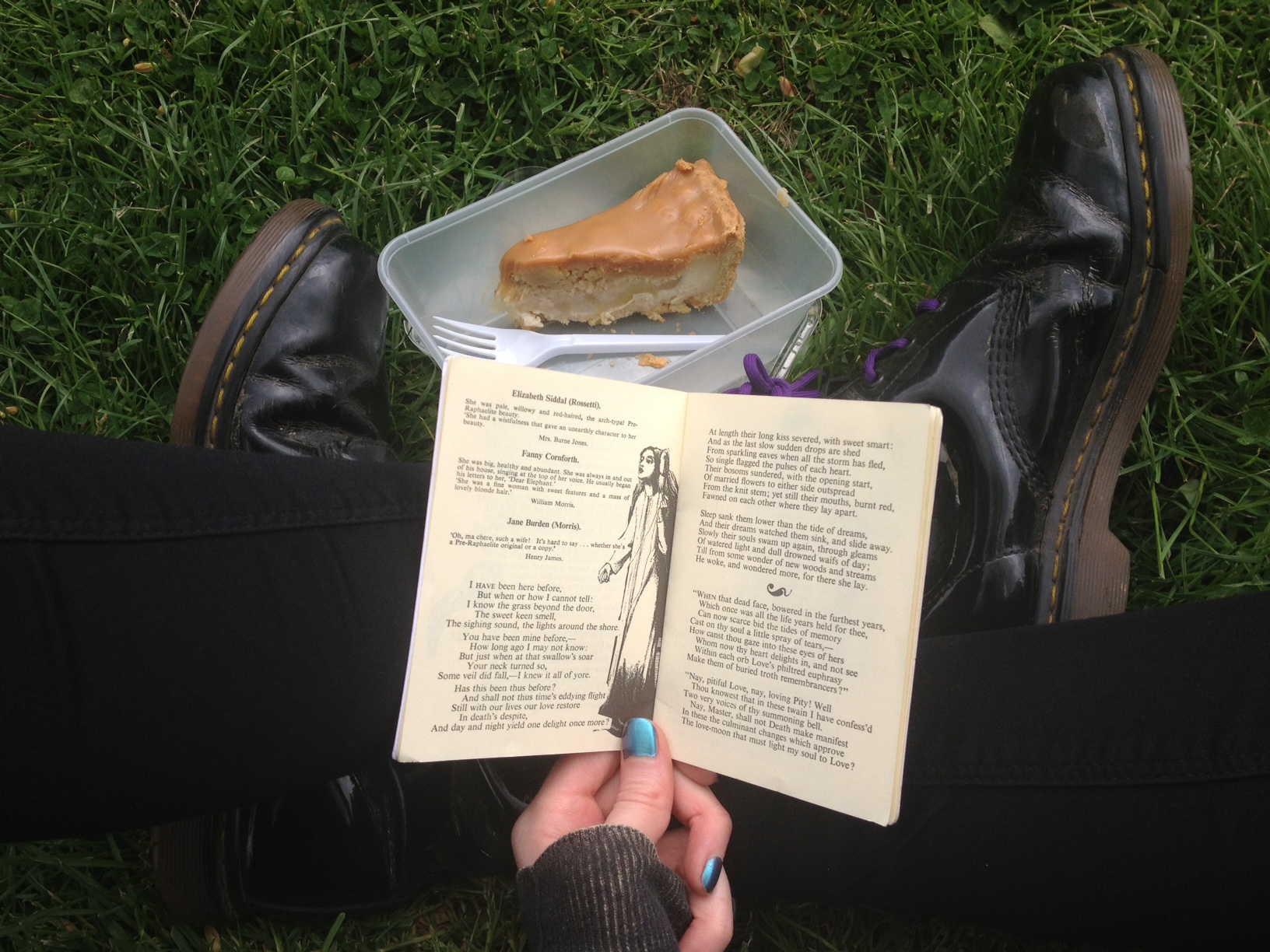

Anyone who’s experienced long periods of sleeplessness knows it’s Hell. Insomnia dogged Dante Gabriel Rossetti most of his life. When he was well, he’d often work until dawn and sleep during the day. When he was ill in the 1860s and ’70s, sleep evaded him completely, turing him onto sedative drugs and stiff doses of whisky – bad news for a man who’d been almost teetotal most of his life.

Written in 1881, a year before his death, Insomnia was one of Rossetti’s last poems. With its lulling, almost seasick rhythm and disordered sense of time, I think the poem captures the way in which sleeplessness dulls and heightens the senses simultaneously, trapping the sleepless one in a purgatorial state of memory, desire, and regret.

Insomnia

Thin are the night-skirts left behind

By daybreak hours that onward creep,

And thin, alas! the shred of sleep

That wavers with the spirit’s wind:

But in half-dreams that shift and roll

And still remember and forget,

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Our lives, most dear, are never near,

Our thoughts are never far apart,

Though all that draws us heart to heart

Seems fainter now and now more clear.

To-night Love claims his full control,

And with desire and with regret

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Is there a home where heavy earth

Melts to bright air that breathes no pain,

Where water leaves no thirst again

And springing fire is Love’s new birth?

If faith long bound to one true goal

May there at length its hope beget,

My soul that hour shall draw your soul

For ever nearer yet.

Found Drowned – George Frederick Watts

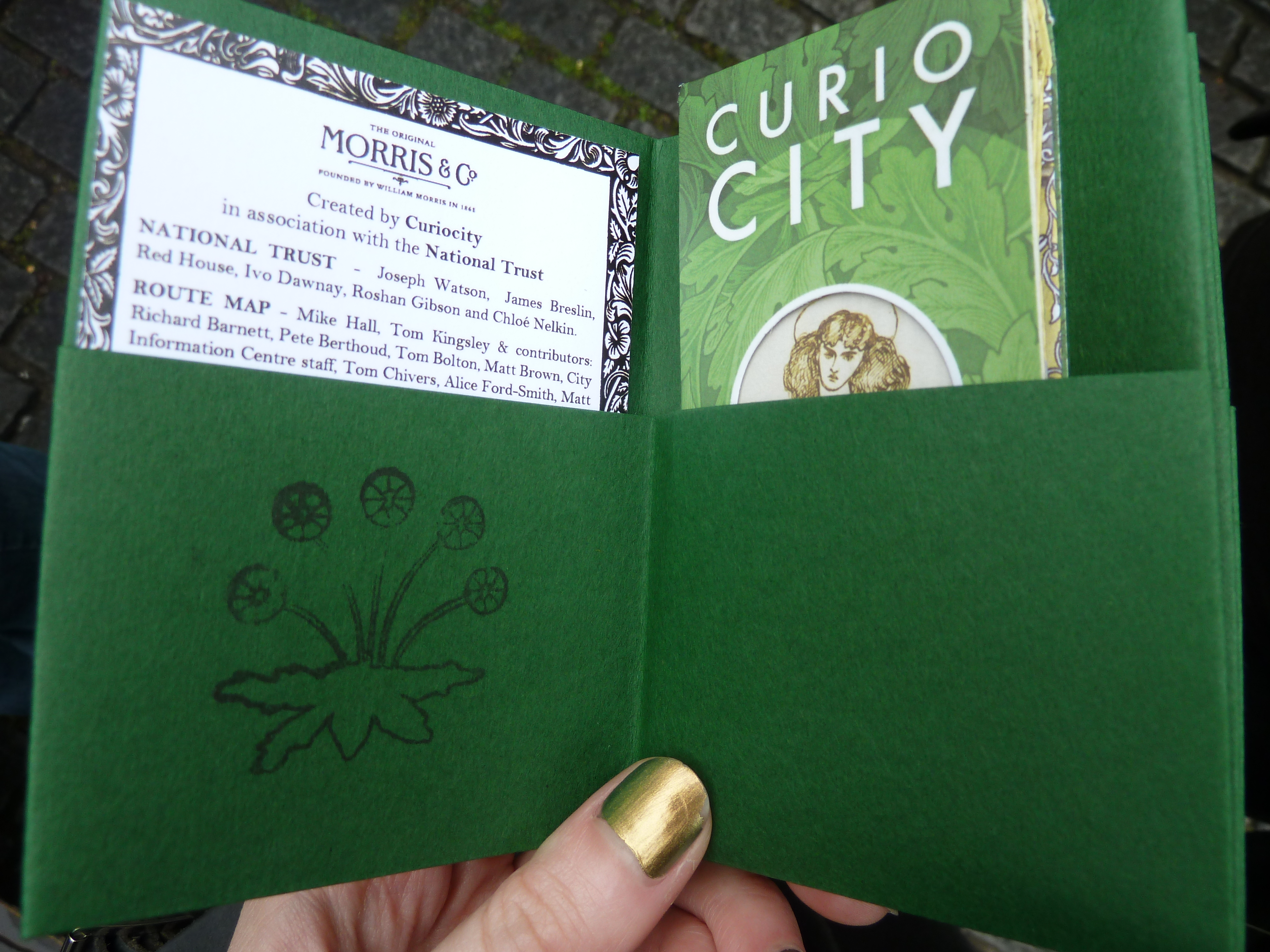

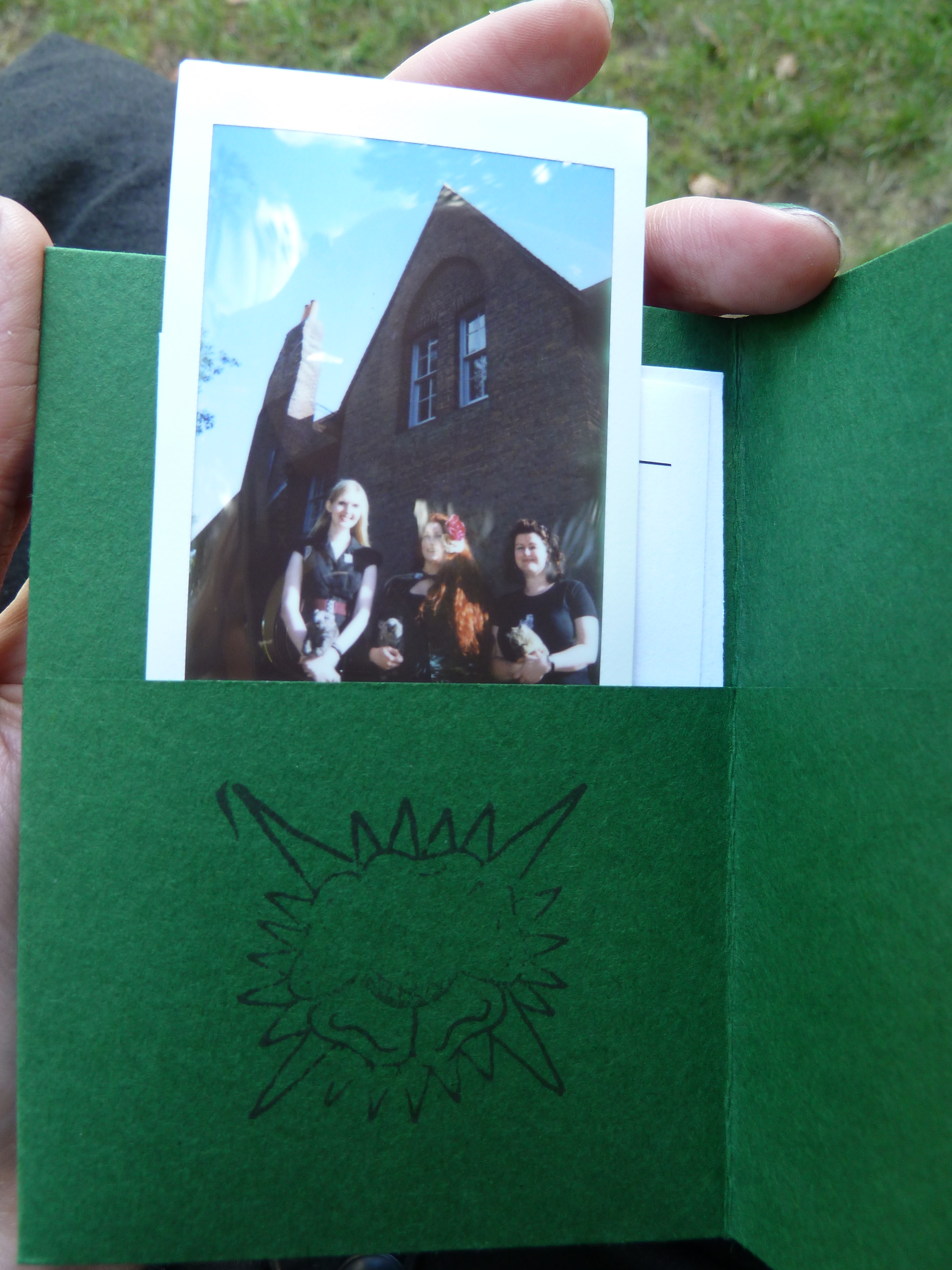

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

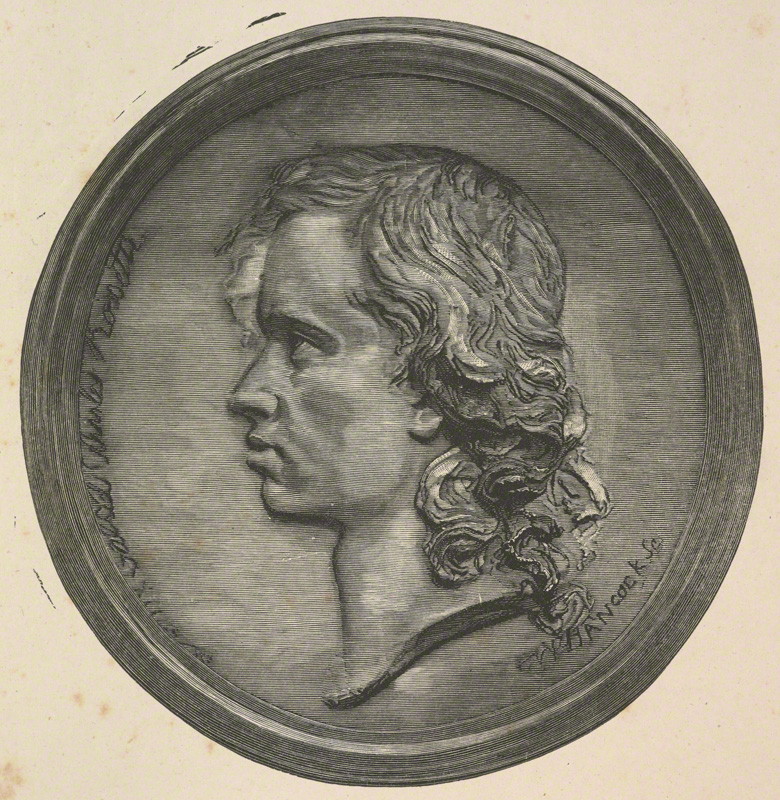

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.