One of the pleasures to be had from Pre-Raphaelite artworks is spotting the cameo appearances: Millais lying on an ironing board, Fred Stephens ignoring the fairies, or Lizzie Siddal’s hair on Jesus’ head… It’s fascinating to see the individual artists’ stamp on a set of familiar features.

Despite being a compulsive fidget, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was, according to William Holman Hunt, a ‘good-natured’ sitter. His Italianate features appear in many PRB works, and likenesses of him, from sketches dashed off in chop houses to carefully-rendered portraits, often provide an interesting insight into the dynamic of the group at the time.

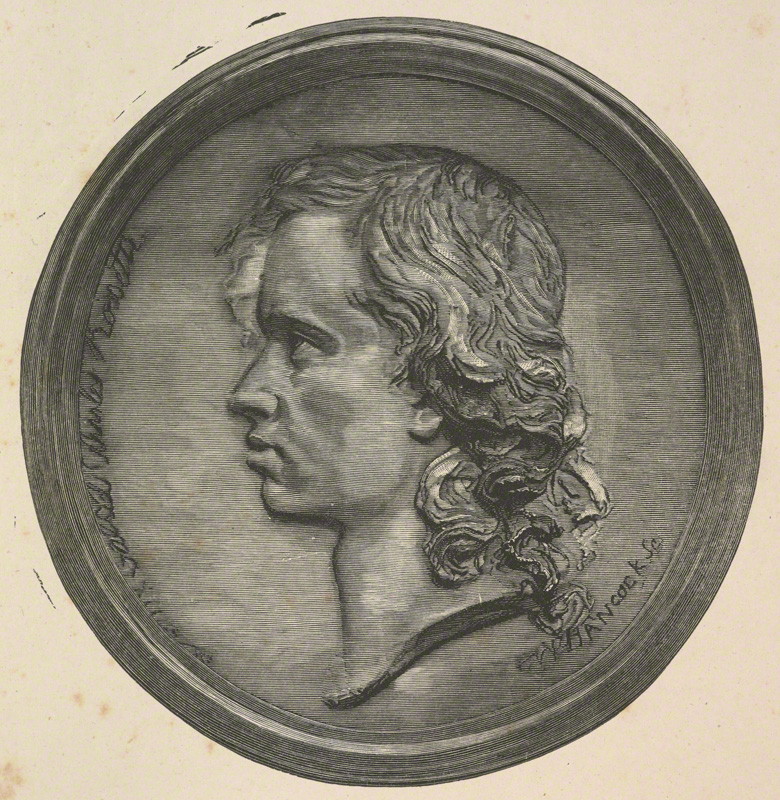

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

John Hancock (not to be confused with the American periwig enthusiast) is one of those fleeting blips on the radar of PRB history. From the glimpses we get of Hancock, it seems he was one of the many little fishes swept up by Gabriel’s net of enthusiasm. (Everyone was a stunning painter! Even if he’d never touched a brush.) Hancock’s young cousin Tom was certainly bewitched by this long-haired teenager bursting with admiration for Shelley and Keats. “How much I owe to listening to his talk at a very impressionable age,” he later wrote.

Like everyone else Gabriel was fond of, Hancock received a ribbing in verse. Here he is, getting on everyone’s nerves at a PRB gathering:

Dante’s Beatrice by John Hancock

The hop-shop is shut up: the night doth wear.

Here, early, Collinson this evening fell

“Into the gulfs of sleep”; and Deverell

Has turned upon the pivot of his chair

The whole of this night long; and Hancock there

Has laboured to repeat, in accents screechy,

“Guardami ben, ben son, ben son Beatrice”;

And Bernhard Smith still beamed, serene and square.

By eight, the coffee was all drunk. At nine

We gave the cat some milk. Our talk did shelve,

Ere ten, to gasps and stupor. Helpless grief

Made, towards eleven, my inmost spirit pine,

Knowing North’s hour. And Hancock, hard on twelve,

Showed an engraving of his bas-relief.

(Rhyming ‘screechy’ with ‘Bay-ah-tree-chi’ – amazing. Almost as good as ‘wombat’ with ‘flings a bomb at’.)

But not everyone took to Hancock. Gabriel’s brother William described him as ‘an ungainly little man, wizened, with a long thin nose and squeaky voice’. Such venom was possibly because he failed to produce promised funding and content for The Germ. It certainly wasn’t the last time William took the hump with someone who encroached upon his and Gabriel’s twin-like bond – see Lizzie Siddal, Fanny Cornforth etc – but, tantalisingly, we don’t have details.

Unlike the majority of the PRB circle, Hancock had steady financial backing from his family and experienced early success, exhibiting successfully in London and Paris and gaining widespread praise for his lovely plaster statue of Dante’s Beatrice. But something, somewhere, went wrong.

Hancock died of gastric irritation and exhaustion just after Christmas 1869, aged only 41, with just £20 to his name (very roughly, £1400 of today’s money). In his obituary, The Athenaeum lamented: ‘the anticipated progress of the sculptor was somewhat suddenly stayed and not renewed’. We do know that Hancock asked to use the PRB initials, but, for unknown reasons, was never permitted to do so. William alluded to ‘unfortunate circumstances into which it is not my affair to enter’ (but apparently enough of his affair to draw everyone’s attention to in print).

What happened to Hancock between the lovely plaster medallion of the teenage Gabriel and his early death? I’d love to know.

John Hancock the Sculptor was a nephew of Thomas Hancock [1789-1865] .When his Father died in Cornwall John the Sculptor and his 6 brothers and sisters were adopted by their Uncle Thomas and sailed by ship from Falmouth up and through the Thames and to London to live with their Uncle Thomas Hancock the fist man in Britain to scientifically describe ,patent , and name the vulcanization process of rubber.Thomas was the Senior partner of his own rubber manufacturing business

and of the Charles Macintosh Ltd Company.He is known as the Father of British Rubber. John the Sculptors other uncle was Charles Hancock [1802-1877] a listed animal and sporting painter and an alumni of the Royal Academy Schools.

Another uncle of John the sculptor was Walter Hancock [1799-1852] the inventor of the first practical steam carriage omnibus.John the sculptors father was also an inventor and in his early life an assistant to Sir Humphry Davy at the British Institution.He worked much on the miners safety lamp and lived in the birth home of Sir Humphry Davy in Cornwall until his death trying to perfect the safety lamp.John the sculptor never married and was financed by his uncle Thomas all his life. He did works of art and sculptured reliefs on several famous buildings in London and at the great exhibition in London.He grew up in Fulham,Cornwall, and his uncle Thomas` home Marlborough Cottage on Green Lanes Stoke Newington in a loving religious family.

I have written a bit on John Hancock the sculptor in Benedict Read and Joanna Barnes’s Pre-Raphaelite Sculpture… 1848-1914. (Lund Humphries/The Henry Moore Foundation 1992) ‘John Hancock: Pre-Raphaelite Sculptor?’ pp 71-76 and illustrations including one of his studio showing many of his known works. His splendid Penserosa is in the Egyptian Hall in the Mansion House in London, and an earlier version is at Osborne, a gift by Albert to Queen Victoria for her ‘birthday table’ in 1857.

He also appears in the Oxford DNB written up by Martin Greenwood (the expert on ideal sculpture – maybe you had wondered why, except for one grave marker, JH only produced ideal subjects? His rich uncle Thomas may have been the answer!)

Nor do we know who Eliza Jane, otherwise Hancock, his widow and administratrix of his goods when he died in 1869?

Thanks, Tom. Didn’t know about the gift from Albert to Victoria.