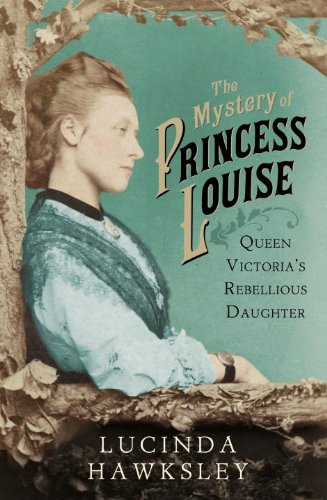

With her latest book, Lucinda Hawksley delves where the monarchy would rather she didn’t.

The life of Princess Louise is one clouded by rumours and misdirection. Queen Victoria’s fourth daughter was said to be simultaneously difficult and charming, dense and witty, beautiful and naughty. With her files still closed to researchers and the public alike, getting a good look at this headstrong woman is a challenging task, fraught with dead ends and muffled hints of scandal. Hawksley’s new biography is the closest we’ve yet come to the true face of ‘Loosy’.

“Luckily the habit of moulding children to the same pattern has gone out of fashion. It was deplorable. I know, because I suffered from it. Nowadays individuality and one’s own capabilities are recognised.” – Princess Louise in a newspaper interview from 1918.

Individuality and independence were luxuries Louise refused to take for granted, likely because Queen Victoria’s treatment of her children was toe-curlingly cruel. The Queen frequently communicated through notes delivered by servants (even when the child at fault was sitting beside her) and laced every affectionate statement with a critical undercurrent. Even when they flew the nest, Victoria would do her best to interfere in her children’s lives to a stifling degree. The psychological effects make for heart-rending reading. When Louise’s father, Prince Albert, died, the thirteen-year-old cried out, “Oh, why did not God take me? I am so stupid and useless.”

It is not surprising that Louise strove to be the polar opposite of her overbearing mother. While the Queen deplored the concept of equal rights for women, Louise admired the drive and ambition of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. The Queen adored Scotland – Louise craved sunshine. The Queen was a stickler for propriety, but Louise, who took on many of Victoria’s official duties during her long mourning for Albert, would openly remark her mother simply couldn’t be bothered any more. The Princess’ charismatic disregard for protocol made her charming, yet her mother seemed set on the idea that Louise was had learning disabilities, or was, as she put it, “naughty and backwards”. Most likely, the artistic young woman was bored.

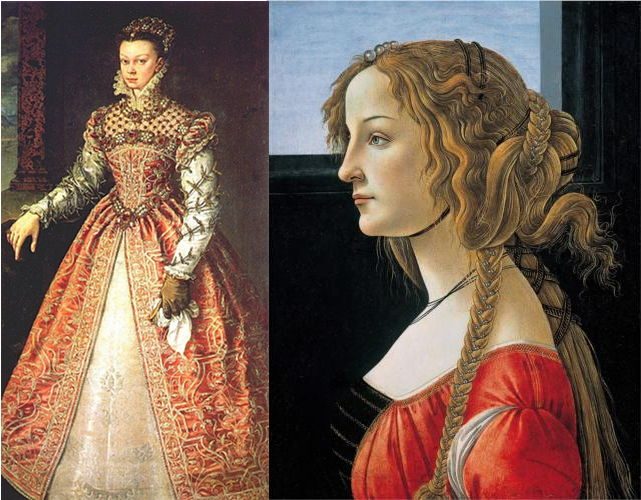

Louise, with Pre-Raphaelite accessories.

This frustration found release in the hard physical work of sculpture. Although William Michael Rossetti took a public swipe at her, tartly (but also quite rightly) stating that an artist who happens to be a royal cannot be judged on merit alone, Louise was genuinely a talented and thoughtful sculptor. She befriended a number of the Pre-Raphaelites (though Dante Gabriel Rossetti was out when she called) and adopted their sense of style, moving in Aesthete circles among radical thinkers, to the horror of her class-conscious mother.

The biography sensitively charts the ups and downs of Louise’s unconventional marriage to the homosexual Marquess of Lorne, a man she came to detest, and later to platonically respect. Rumour had it, the Princess knew Lorne picked up soldiers in the park near their apartments. She consequently had the windows facing them bricked up. More shockingly, Louise herself had a number of affairs. This, Hawksley surmises, is why her files are so forcefully concealed to this day. Although her brother Bertie was a famous philanderer, and even Queen Victoria enjoyed a healthy sex life, there are indications that before meeting Lorne, Louise had done the unforgivable and been an unwed teenage mother – via her brother’s tutor. How Louise concealed this alleged pregnancy – and what may have happened to the child – provides a fascinating insight into the Victorian double standards of gender and sexuality, and also Louise’s indomitable spirit.

Louise’s statue of her mother at Kensington.

The scandals don’t stop there. Louise was at ease in the company of men, and therefore attracted a great many admirers, including the artist Sir Edgar Boehm. Despite efforts to wipe the affair from the record, it would seem Boehm died during sex with Louise, leading to comical rumours that the body had been rolled up in a carpet and bundled into a cab to avoid a scandal. That Louise continued to be a vivacious, fun-loving woman after this and other such traumatising events is testament to the inner strength forged by years of her mother’s bullying.

But the book is much more than a catalogue of naughtiness. Far some being yet another fawning royal biography, Hawksley’s The Mystery of Princess Louise is unflinching about the human flaws of her subjects. Hawksley conjures the nineteenth century in an accessible way, showing the royal family as being an active part of the great Victorian machine rather than simply perching in its upper echelons. She regularly brings up the contemporary republican viewpoint, which may surprise and interest readers. The same arguments are debated today.

Hawksley also brings up a very important point: Queen Victoria’s diaries as we know them now are the product of heavy editing by ‘the arch-inquisitor’ Princess Beatrice. We will never know her stronger comments on Louise’s liberal lifestyle or the lengths she went to to conceal her daughter’s teenage misdemeanours. In the mid-twentieth century, Princess Margaret made an attempt to research the Princess Louise – even she was barred from the most sensitive records. What we do have is the testament of the companions, servants and chance encounters Louise had during her long life; people who found Louise to be an engaging, headstrong, charming, and exceedingly modern artist and princess.

Lucinda Hawksley’s The Mystery of Princess Louise: Queen Victoria’s Rebellious Daughter is out on the 21st of November 2013.

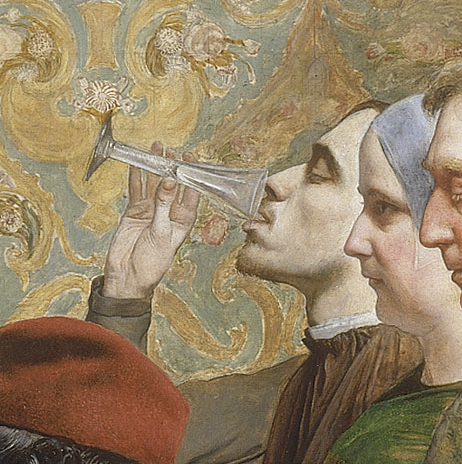

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

Whilst fully admitting it feels as if I left both my legs somewhere in Greenwich, this weekend’s Curiocity Pre-Raphaelite Pilgrimage was a great (and exhausting, oh good God, exhausting) way to spend a Saturday.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

At the same time, across London, 300 people were arrested at an EDL rally. We were reminded that for every person generating cruelty and ugliness there is more than one devoted to beauty and equality.

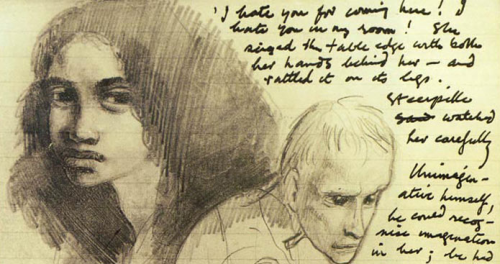

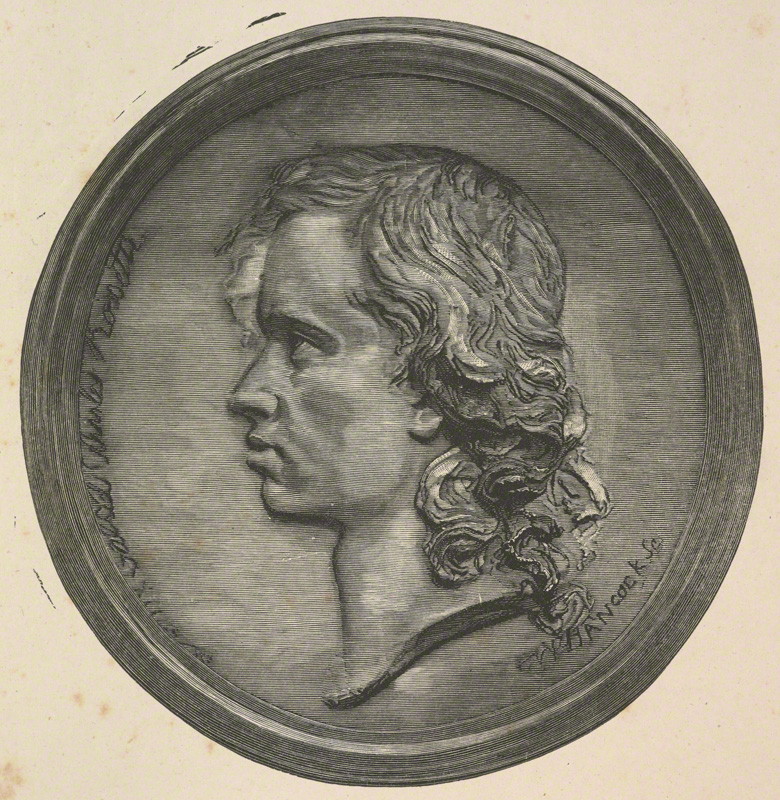

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.