Stephanie of preraphaelitesisterhood.com wants your museum pictures! Share them here and enjoy the gallery of starry-eyed loons.

That’s me in the corner. That’s me in the spotlight. Staring down The Bridesmaid.

Stephanie of preraphaelitesisterhood.com wants your museum pictures! Share them here and enjoy the gallery of starry-eyed loons.

That’s me in the corner. That’s me in the spotlight. Staring down The Bridesmaid.

With kind permission from the University of British Columbia, and the help of author of The Rossettis In Wonderland, Dinah Roe, I have a Christmas treat to share with you: Mama Frances Rossetti’s recipe for a frightfully boozy rum punch!

The Rossetti family’s little London parlour was always crammed with displaced Italian revolutionaries, carousing and debating while the cat warmed herself in front of the fire. Christina talks about “chestnuts, cake, and a social glass of grog”, although Dante Gabriel didn’t drink at all until much later in life. (That didn’t stop him, as a child, from feeding beer to a hedgehog and watching it stagger about, the unusual boy). However, I like to think he partook of the occasional sip of family punch. Especially if it was anywhere near as tasty as my attempt!

Let’s give it a go, shall we?

Frances doesn’t give especially detailed instructions, so most of this is guesswork verging on generosity. Here’s the recipe as it appears in Frances’ recipe book:

2 lemons

1 orange

Rum

Brandy

Lump sugar to taste

The lemons being first scraped white, therewith, boiling water.

Looking for further details, I found this fantastic article on Charles Dickens’ favourite punch, circa 1847, involving a pint of rum (!) and a glass of brandy. That, between myself and Mr May, would be lethal, so I’m going to tone down the quantities a bit for the sake of propriety.

Yes, this is classed as research.

I sliced the lemons (first scraping them white with a knife, because for some reason I don’t own cheese grater) and cut the orange into four. I ended up slicing the lemons in half because I didn’t quite believe the juice would get out through the zest. Maybe that was a mistake. We’ll see.

On the hob, I boiled a pint and a half of water, brought it off the boil and added the fruit. I left the lot to simmer for three minutes while I repeatedly got the maths wrong and ended up deciding on half a pint of rum, which, on reflection, was a bit much. Oh, well.

Both the brandy and rum were the finest El Cheapo supermarket bathtub plonk, because, unlike the myriad characteristics of gin, all brands of rum taste to me like aviation fuel. So I added the half pint of rum directly into the pan over a gentle heat, letting it ‘mull’ a bit in the fruit juice, which was beginning to smell pleasantly like Christmas cake.

I then ‘measured’ out roughly a quarter of a pint of brandy. I’m not used to brandy (the stuff I used smelled like a dentist’s surgery) so I took Charles Dickens’ advice (sorry, Uncle Thomas) and spooned it in, setting it alight spoon by spoon. To what benefit, I can’t say, but it made a nice “voomph!” sound and made me feel like some kind of pagan Goddess of winter debauchery.

At this point, mind your hair.

So! Next, I had a little taste test, resulting in flashbacks to childhood toothache remedies. It was quite bitter, and the lemons had crumpled slightly, leaving floating bits of lemon on the surface. I don’t know what Mrs Rossetti would have done, but she seemed the sensible type, so I removed the lemons and let the oranges take over.

I added a liberal quantity of brown sugar, and stirred the punch for a few minutes. The rum really needs a bit of sweetness to balance it out, but it’s all personal taste.

Once the lemons were out, the punch began to taste much more recognisably fruity (I suspect winter lemons in this country are just a bit mean-tasting) and the sugar and alcohol complemented each other nicely.

* Don’t let it boil

* Take a distinctly un-Victorian swizzle stick and give it a good stir.

* Pour into a tall glass because I don’t own any other kind of glass.* As Christina wisely suggested, add cake.

It actually tastes delicious. It is distinctly piratey – grog! – though the citron gives it a more festive kick than something you’d swig before pillaging a small coastal town.

Queer loaves are the best loaves.

Frances did her best to reproduce Italian food for her family. Indeed, Dante Gabriel was still sourcing cannelloni from Soho decades later. However, I always think of him when I buy my Christmas panettone. In 1874, he wrote to Frances:

I have been painting from a little Italian boy who highly appreciates Toscone; but on my giving him a piece of Panattone (that queer loaf) he said in a startled tone, “Quanto costa questo?”* I replied “Non credo molto,” & he rejoined “Crederei quasi neinte”. Such was his verdict on that comestible.

To complete the experience, I’m going to curl up on the sofa with my copy of The Collected Letters of Jane Morris, an incredibly thoughtful gift from Becki of Fifteen Precise Facts.

Buon Natale, everyone!

*“How much is this?”

“I do not think much.”

“I would think almost nothing.”

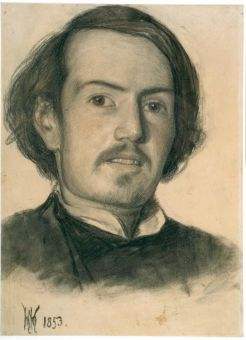

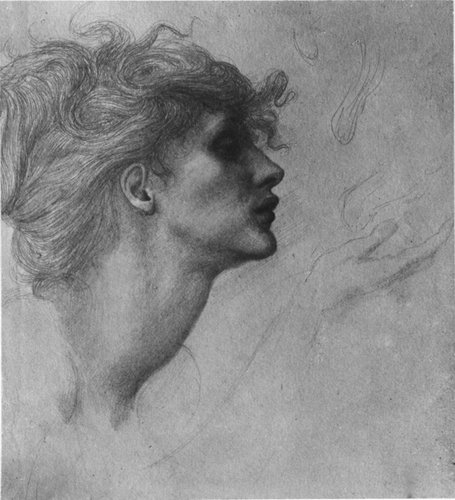

Since I blogged about Walter Howell Deverell’s Twelfth Night, I’ve been wanting to spend a bit more time with the poor doomed boy. So here’s a treat – the study for his ill-fated The Banishment of Hamlet. Dante Gabriel Rossetti was most likely the model for Hamlet.

Walter is mostly remembered as the ‘lost’ Pre-Raphaelite who discovered Lizzie Siddal in a hat shop. Had he accepted full membership into the Brotherhood, he may have been better regarded today, but Walter was the eldest of seven surviving siblings, motherless and later fatherless, too. Linking his name to a controversial gang of artistic upstarts seemed like another way to make life difficult for him and his dependants. As such, he tends to be relegated to a walk-on character in the story of Rossetti’s love-life.

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

Looking like a Victorian Johnny Depp, Walter had a mildly-exaggerated reputation for driving girls to distraction, although his infamous comment about PRB standing for “penis rather better” was probably in reference to the constant pain he would have suffered with the Bright’s Disease that eventually killed him, aged 26. Having had acute pyelonephritis aged 14, I can attest to its utter mind-bending awfulness, which is one of the reasons I feel so sympathetic towards poor old Walter.

The Banishment of Hamlet was doomed from the beginning, receiving a typically venomous Athenaeum review:

Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.

The painting was roundly abused when it appeared at the National Institution in 1851, went unsold, and then, depending on the source, was either blown up in a gas accident or lost in a fire. The study above resides in the Ashmolean under another name, making it difficult to trace.

William Michael Rossetti penned a kinder review*, praising the prince’s moodiness in the same terms he reserved for descriptions of his brother around the same time:

There is a certain brooding indolence in his whole figure; irresolution is shown in the movement of his hand, and mingles even with the settled scorn of his eyes.

The ‘delinquent school-boy’ attitude of Walter’s Hamlet may well have been inspired by his friend’s air of insouciance; his habit of pulling his sleeves down over his hands and flicking his long fingernails when nervous. The painting certainly seems to have been the subject of jokes between the pair as seen in these cartoons by Rossetti in which the lads’ Irish patron MacCracken erupts with delight at the sight of something that looks an awful lot like Walter’s Hamlet:

‘The long expected Deverell, arriving at length/ find M’C laid up with the sickness of/hope deferred. Owing to an unfortunate error/of packing, the patient is strongly excited on seeing it/and there seems every reason to fear the worst.’ – DGR’s caption

There are lots of these over on The Rossetti Archive, suggesting that Hamlet’s unsaleability was a source of humour rather than anguish. Indeed, Walter exhibited a strange, fatalistic disinterest in the way no one seemed to want his pictures.

I love the way Rossetti always depicts himself as scruffy and round-shouldered next to Deverell’s rather natty figure. Perhaps the ‘delinquent school-boy’ comment appealed to his sense of humour, or perhaps it was a gentle dig at Walter’s popularity with the girls.

It’s a shame that Walter has become a footnote in Rossetti and Siddal’s relationship. There’s a sweetness to his surviving paintings that I find refreshing. Pretty girls pose with pretty birds, and Shakespearean characters totter about in pointy shoes and bright tunics like tableaus from a child’s picturebook. It would be easy to write them off as twee, and perhaps that’s precisely what happened, but I think Walter may have sought out idyllic scenes on purpose, what with the stress of his family responsibilities, the purgatives prescribed for Bright’s Disease, and the eventual realisation that he wasn’t going to make it. His poetry, published in The Germ, betrays a troubled frame of mind:

Though we may brood with keenest subtlety,

Sending our reason forth, like Noah’s dove,

To know why we are here to die, hate, love,

With Hope to lead and help our eyes to see

Through labour daily in dim mystery,

Like those who in dense theatre and hall,

When fire breaks out or weight-strained rafters fall,

Towards some egress struggle doubtfully;

Though we through silent midnight may address

The mind to many a speculative page,

Yearning to solve our wrongs and wretchedness,

Yet duty and wise passiveness are won, —

(So it hath been and is from age to age) —

Though we be blind, by doubting not the sun.

Walter died on the 2nd of February 1854. He only sold one painting in his lifetime.

Rossetti wrote to Ford Madox Brown: “He had been told in the morning that he could not live through the day and he appeared to receive the announcement without emotion or surprise, saying he supposed he was man enough to die”.

It was the first big loss of Rossetti’s life. “I have none left who I love better, and I doubt whether any who loves me so well,” he wrote to Walter’s family. By 1870, he was still trying to sell The Banishment of Hamlet to raise funds for Walter’s surviving family. If he had succeeded, perhaps we would still have it today.

*It has been argued this was DGR writing under WMR’s name, but I’m going to trust the original citation for the time being.

When I was fifteen, I had a summer work experience placement at Ipswich’s psychiatric hospital. St Clements was one of the old ‘asylum’ style hospitals with high-ceilinged wards, green grounds, and a big, romantic entrance hall like something from a smart Edwardian hotel.

When I was fifteen, I had a summer work experience placement at Ipswich’s psychiatric hospital. St Clements was one of the old ‘asylum’ style hospitals with high-ceilinged wards, green grounds, and a big, romantic entrance hall like something from a smart Edwardian hotel.

Among the patients I got to know, there were two shuffling old men who always stuck together. They rarely said a word, even to each other, and spent their days in the potting sheds propagating seeds to sell in the hospital shop. Someone told me these two men had spent their whole lives in the hospital; that their mothers were sent there because they’d given birth out of wedlock. I was sceptical, not because I didn’t believe such awful things had happened, but because I thought that particular social shame was Victorian in origin.

However, one of the many surprising things I learned when we hightailed it to Highgate this week for a talk hosted by Sarah Wise, author of Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England, is that the old story of the dissolute male knocking up the maid and having her put away in a mental hospital to avoid a scandal was in fact a twentieth century phenomenon. And, more surprisingly, Victorian men were more likely to be maliciously accused of insanity than women – because that’s where the money was.

Those who were eccentric, wayward, rebellious, different in some fashion or even just stood in the way (often of money), were often locked up at the behest of family members who stood to benefit. They were aided and abetted by a growing number of ‘mad doctors’ who readily certified ‘madness’. There was money in the lunacy trade — certainly more than in certifying people as sane…

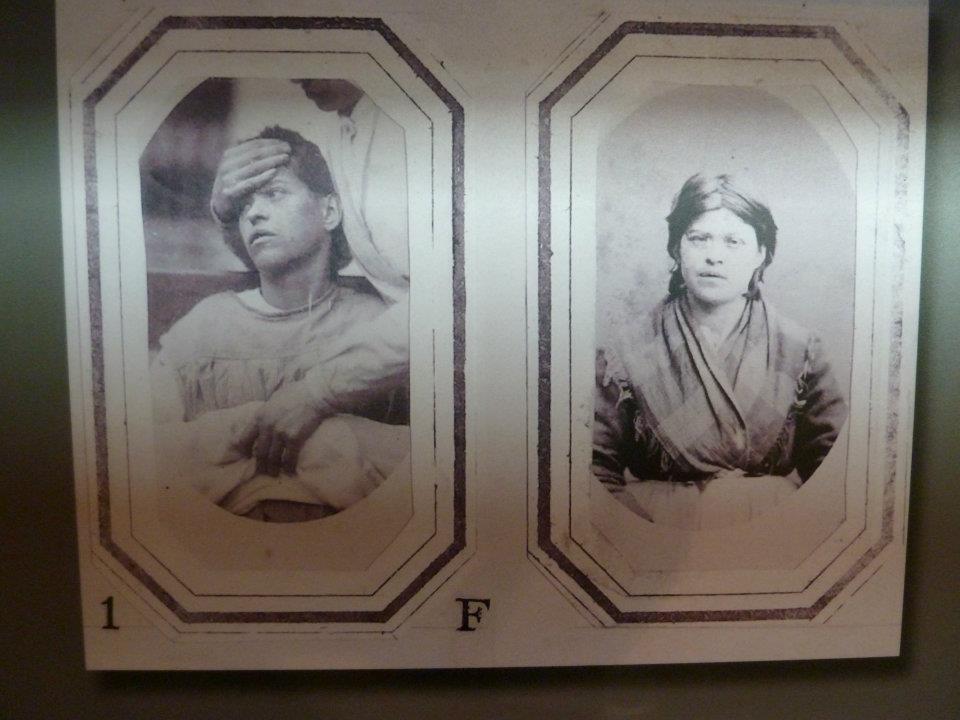

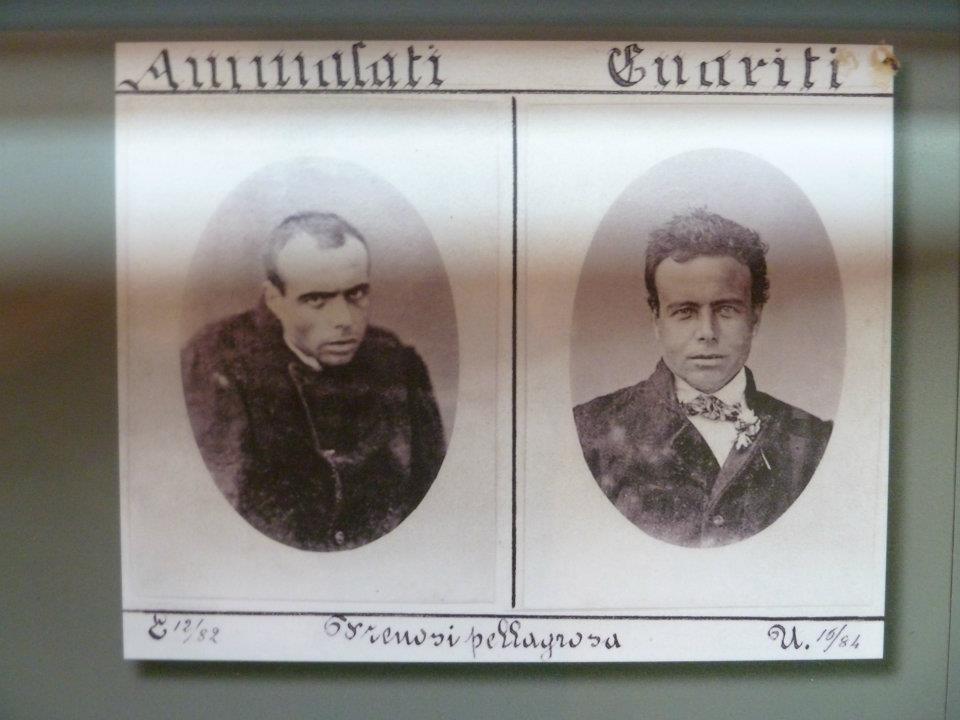

I haven’t yet read the book, but the talk reminded me of when, in Venice this summer, we took the vaporetto out to San Servolo, the so-called ‘island of the mad’ to see the remains of the hospital there. Most of the building is now occupied by the University of Venice, but the pharmacy remains intact, along with a small museum and an imposing white chapel amongst the botanic gardens, radiating heat.

I haven’t yet read the book, but the talk reminded me of when, in Venice this summer, we took the vaporetto out to San Servolo, the so-called ‘island of the mad’ to see the remains of the hospital there. Most of the building is now occupied by the University of Venice, but the pharmacy remains intact, along with a small museum and an imposing white chapel amongst the botanic gardens, radiating heat.

Like the subjects of Sarah Wise’s research, most of the inmates of San Servolo were not mentally ill at all, but dipsomaniacs (alcoholics) or suffering from malnutrition. Being cheap and plentiful, polenta was the dietary staple of the Venetian working classes, but too much of it can cause hallucinations and erratic behaviour. The doctors only realised this when patients who’d come in raving returned to the community – and thus their regular diet – only to be readmitted soon later with the same old symptoms.

In the museum, there was a long, long line of before-after shots of some of the nineteenth century patients, as if physical appearance can ever really tell us anything.

Having had depression for most of my adult life, there’s always a slightly guilty sense of “there but for the grace of…” when viewing the records of people in similar situations a hundred or so years ago. As Sarah Wise explained, those suspected or accused of mental illness in England were at the mercy of unqualified ‘mad doctors’ and The Commissioners of Lunacy (which sounds like a rubbish steampunk band), a system open to abuse, especially when the theory of monomania drifted across the continent.

Monomaniacs were defined as individuals who appeared fully sane except for one triggering factor, one preoccupation. Monomania was a worrying concept for the public, a) because it was a French theory and therefore probably cobblers, and b) because it made them confront the possibility that mad people looked and behaved just like everyone else.

Which, in my experience, sounds precisely like today’s attitudes.

But doesn’t everyone, healthy or otherwise, have a right to eccentricity? Particularly in England, or so the English tell themselves. And this cognitive dissonance led to some astonishing, uplifting cases of the public turning out in droves to support the accused, even going as far as staging daring rescues. In response to the incarcertion of Lady Lytton — a bona fide case of a disgruntled husband using his influence to silence an intelligent wife — The Somerset Gazette printed in 1858:

Rouse, and assert Old England’s boast

With indignation rife;

From Orkney to The Scilly Isles

Cry ‘Liberty in Life’!

I can’t wait to get stuck into the book. Thank you, Sarah, for an eye-opening talk.

While reaching this article, I was saddened to discover that St Clements, with its vast grounds and grand halls, was turned into a middle class golf resort in 2011. I wonder what happened to those two old men who knew nothing but the asylum.

If you have an hour to spare on this chilly Armistice Day, I recommend spending it with Derek Jarman’s haunting 1989 film War Requiem. With no spoken dialogue it has the same dreamy, shadowy quality that made Caravaggio one of my favourite films*, juxtaposing gentle, balletic human interaction in chalky light with painterly nightmare sequences suggestive of Hieronymus Bosch’s Hell. All shot on a budget of about £3.50.

If nothing else, watch the sacrifice scene at 43:06. Nathaniel Parker looking like a moustachioed Edwardian angel as the cigar-puffing masses watch from a safe distance, rouged and smiling, is one of the darkest, most gorgeous few minutes of film I’ve ever seen. Nathaniel’s trusting little smile – oh, God.

* I use Caravaggio as a method of gauging character. If you can sit through it happily, you’re an alright sort. If you love it as much as I do, you can stay.

“I am inclined to think that sort of thing is mostly rubbish” – William Morris, on his own work.

I managed to crawl my way out of last week’s all-pervading October fog – Dickensian or Hitchcockian, depending on the monsters looming out of it – to get to the Edward Burne-Jones exhibition at Kelmscott Manor.

The Body Beautiful: Burne-Jones At Work, was partly a goodwill gesture on behalf of The Tate, who carefully dismantled William Morris’ Kelmscott bed and took it to London for the Pre-Raphaelite: Victorian Avant-Garde show*. To be honest, I was expecting the Tate’s rejects. (“We’re having Love Among The Ruins. You can have this teacup.”) But the collection of hazy nudes and tactile studies, although small, was well worth the three-hour drive from Cambridge.

“It’s so flat that to see anything is not easy, and when you do see it, it isn’t worth seeing” – Rossetti, indulging in a grump.

For those of you who haven’t ventured out into the wilds of Lechlade to William Morris’ earthly paradise, let me first explain that Kelmscott exists inside a cosmic bubble. The modern world has been kept at such a distance, you can comfortably believe it no longer exists. The house and surrounding farm buildings have been preserved as sensitively as possible, encouraging visitors to see it as a home and not a museum. The weather is constantly mellow and glorious, and the carpark and the cafe are minor details – you can convince yourself that Morris has just pootled off to Iceland, and Jane is probably embroidering in the next room.

The illusion is compounded by little domestic details unfettered by velvet ropes. Rossetti’s satinwood writing desk (on wheels!) is so dinky, I wouldn’t get my legs under it. The general smallness of the house’s Victorian occupants was especially apparent in Morris’ overcoat, hanging from a door in the same room. Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Paris says the label, as if fresh off the catwalks. You can imagine him bustling about in it.

And then, upstairs…

The Body Beautiful: Burne-Jones at Work

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

Of the small collection of studies, especially striking was the snake-necked Disiderium, the head of Amorous Desire, as dangerous as she is gorgeous. While some of the sketches looked scratched out and hurried, Disiderium oozes off the paper with the same anthropomorphic sensuousness present in Beguiling Merlin. More ‘the body bewitching’ than ‘the body beautiful’.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

It’s a shame the exhibition was so little-publicised, because fans of Ned would really have loved this, especially given the extraordinary setting.

The certain secret thing he had to tell

The certain secret thing he had to tell

Some of Rossetti’s worst illness and addiction was played out at Kelmscott, so it’s a sad place as much as a lovely one. When I last visited, I was in the midst of post traumatic stress disorder, and it was easy to see how the landscape of flat, marshy fields and slowly-flowing streams could be as much a help as a hindrance to someone suffering from an untreated mental illness. May Morris remembered him in his black cloak, “tramping away doggedly” across the landscape alone.

Jane, whose collected letters were published this month, doesn’t get much in the way of a ‘voice’ in comparison to the men at Kelmscott. Her job is muse. Embroiderer. In the dining room, I tried to imagine her as Burne-Jones described her at nineteen, laughing “until, like Guinevere, she fell under the table”, and found I couldn’t. Amusingly, on her bedside table today are the collected letters of noted drunkard and amateur sadist Algernon Swinburne, open on a page extolling “cannibalism as a wholesome and natural method of diet”. Oh, Algie, you card.

I have a bone to pick with The Society of Antiquaries.

Rossetti’s bombsite of a paintbox resides upstairs in the tapestry room he commandeered for the light. In hilarious contrast to Millais’ pristine palette, Rossetti’s paintbox looks like something you’d find at the bottom of a skip. All his squeezed tubes (missing their tops, naturally) are congealed together in a shallow tin box encrusted with lead drippings, studio detritus, and a sort of greenish, yellowish coating of grotesquery and rust.

It’s gorgeous.

The room attendant, who very tolerantly said, “I’m touched you react that way” when I basically had a fit of the vapours over the thing explained the paintbox is a conservationist’s nightmare. Like Beata Beatrix, which was restored in time for The Tate, the paintbox contains a certain amount of ‘holy dirt’: original detritus from Rossetti’s studio. The trick is to separate the holy dirt from the decades of accumulated filth and decay without damaging the artefact. The trouble is, they haven’t started the process yet. And from the sounds of it, there are no plans to.

I wish I could share a photograph of it here, but photography is strictly forbidden. There are no postcards of the paintbox either, and because it isn’t labeled, half the visitors are walking by it without ever knowing what it is.

I feel the need to start a campaign. Look here, Society of Antiquaries, print some postcards, and put the proceeds towards protecting that precious paintbox!

* Before any Morris fans worry, the crew photographed each step of the disassembly, so not a single tiny, precious screw will be forgotten when the bed eventually returns.

As it’s National Poetry Day, I’d like to share my favourite Dante Gabriel Rossetti poem. (Besides the one rhyming ‘wombat’ with ‘flings a bomb at’, lest we forget).

Sudden Light was written in 1854, when life was relatively good for Rossetti. This was the period when he and Lizzie Siddal were holidaying in Hastings together, and the romantic optimism of the poem makes it a lovely window into that time.

Sudden Light

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

You have been mine before,—

How long ago I may not know:

But just when at that swallow’s soar

Your neck turned so,

Some veil did fall,—I knew it all of yore.

Then, now,—perchance again! . . .

O round mine eyes your tresses shake!

Shall we not lie as we have lain

Thus for Love’s sake,

And sleep, and wake, yet never break the chain?

There are two versions, with differing final stanzas. This is the earlier of the two – the other was published some time after Siddal’s death, with a more melancholy slant. I prefer the first, but make up your own mind.

Has this been thus before?

And shall not thus time’s eddying flight

Still with our lives our love restore

In death’s despite,

And day and night yield one delight once more?

I spent yesterday trapped in a gridlock of uncomfortably warm bodies amongst the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Yes, it was as fantastic as it sounds.

This post isn’t going to be remotely succinct or clever. I just want to gush. I loved it. So many of my favourite things in one place. And having the opportunity to sit and chat with fellow PRB-lovers afterwards was just terrific.

Kirsty Stonell Walker of ‘The Kissed Mouth’ and I, modelling Doc Martens, the unofficial footwear of PRB-admirers everywhere.

A lot has been said in the press recently, some more sensible than the rest. There’s been the obligatory game of Hunt The Phallus, and general moaning about how the PRB would have been so much better if they’d just dropped a shark into a tank of formaldehyde. But were the PRB truly Avant-Garde?

I come at the PRB from a literature point of view. My MA focused on Rossetti’s cycles of desire and denial in The House of Life. So although I know a fair bit about the PRB’s visual art, the wider subject of Avant-Garde isn’t something I feel I can comment on.

However, I can give my top five moments:

5. I saw Rienzi. It was blue. So blue. Hunt’s colours are so psychedelic and trippy – mountains are purple, flesh is orange, goats are bizarre and terrifying. His work has to be seen to be fully experienced.

4. The passion flowers in Rossetti’s The Blue Bower were like glossy photographs. As Edward Burne-Jones said, Rossetti somehow makes everything look as if it’s under glass, though he swore he didn’t use glaze.

4. The passion flowers in Rossetti’s The Blue Bower were like glossy photographs. As Edward Burne-Jones said, Rossetti somehow makes everything look as if it’s under glass, though he swore he didn’t use glaze.

3. Rossetti’s Paulo and Francesca da Rimini. Strangely washed-out and chalky compared to the print on my wall. Francesca’s incredibly long hair has the texture of real long, fine hair in contrast to the lustrous thickness of the hair in his later work.

3. Rossetti’s Paulo and Francesca da Rimini. Strangely washed-out and chalky compared to the print on my wall. Francesca’s incredibly long hair has the texture of real long, fine hair in contrast to the lustrous thickness of the hair in his later work.

2. Speaking of lustrous hair, Rossetti’s teenage self-portrait was hung in the first room to lure in all the ladies.

1. Walter Howell Deverell’s Twelfth Night. I hadn’t allowed myself to read spoilers about the exhibition, so turning a corner and seeing this was a huge surprise. I was so happy for him.

1. Walter Howell Deverell’s Twelfth Night. I hadn’t allowed myself to read spoilers about the exhibition, so turning a corner and seeing this was a huge surprise. I was so happy for him.

You see, poor Deverell had no luck. So handsome (that’s him in the middle and Rossetti on the right) and so promising a talent, his work was badly hung at the RA, his The Banishment of Hamlet was later destroyed in a gas explosion, and he died of kidney disease and dysentery three months after his 26th birthday.

Deverell’s decline and death hit Rossetti hard. One of the last times Rossetti visited him, “[Deverell] rose up in bed as I was leaving and kissed me, and I thought then that he began to believe that his end was near”.

The whole story is so sad. It was good to see him represented.

I had a few small criticisms, but only on the understanding that the exhibition was wonderful and I’ll probably go back at least twice.

Of course, there were pieces I was dying to see that weren’t included. Julia Margaret Cameron’s Pomona, for one: Alice Liddell, all grown up and threateningly beautiful. And I’m always hoping for a second viewing of a lock of Rossetti’s hair, which I saw at the Fitzwilliam a few years ago (alongside Keats’ hair!) – a sight I never fully recovered from.

Of course, there were pieces I was dying to see that weren’t included. Julia Margaret Cameron’s Pomona, for one: Alice Liddell, all grown up and threateningly beautiful. And I’m always hoping for a second viewing of a lock of Rossetti’s hair, which I saw at the Fitzwilliam a few years ago (alongside Keats’ hair!) – a sight I never fully recovered from.

I did feel that the show could have been organised differently. It was a mammoth undertaking and difficult to tackle, but I felt that the different facets of the Pre-Raphaelite circle needed their own space. There was an element of jumbling that was interesting for people with prior understanding of the PRB, but perhaps confusing for those coming in cold.

I think the problem in creating an entire PRB exhibition is that you’re dealing with so many people who all evolved dramatically in taste and execution over a period of decades. So you’ve got Rossetti offering tiny jewel-toned watercolours in one room, and then massive red-lipped vampiric creatures in the next. You want to ask what happened.

Perhaps a clearer linear structure could have added something. For instance, ‘this is what they hated, here’s how they banded together, here’s how they evolved and the legacy they left’. I also would have loved to have seen at least part of the manifesto emblasoned somewhere, because everyone loves a good manifesto.

And then there was the gift shop. The £25 strings of plastic beads would have left William Morris reeling. Expensive satchels and striped scarves were very nice but had nothing to do with the PRB. We were hoping for a bit more effort. Having said that, my life has been enriched by the possession of a Scapegoat fridge magnet.

Overall, though, what an overwhelming experience. Next up, Edward Burne-Jones at Kelmscott!

In later life, Rossetti liked to shrug off his connection to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. To admirers, he gently dismissed the whole movement as “the visionary vanities of half a dozen boys.”

To which I say “pah!”, because tomorrow is the 164th anniversary of the formation of The Brotherhood – #PRBday on Twitter – and, unlike Claret Day, the celebration is officially sanctioned by The Pre-Raphaelite Society and not simply another excuse to drink red wine and look louche.

This is the autumn of the PRB. My date with The Tate is looming. I’ll be meeting up with Kirsty of The Kissed Mouth and Robyne of Artistic Dress on the first Saturday to empty the Tate’s shop of frighteningly expensive fridge magnets. Then, in October, it’s straight to Kelmscott Manor for the little-advertised Edward Burne-Jones exhibition which will probably prove my undoing.

I’ve tried to avoid spoilers, but… The Tate has Holman Hunt’s Rienzi (full title Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions – what were you thinking, Hunt, honestly?) which was on my wall for five years when I was a student and has been hidden away in a private collection for the entire span of my life. Rossetti modeled for the hero, hence the flying saucer eyes and the my-uncle-knew-Lord-Byron-actually hair. That’s Millais, dead on the ironing board. If I can get a long, clear look at it, I’ll be happy for years.

I’ve tried to avoid spoilers, but… The Tate has Holman Hunt’s Rienzi (full title Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions – what were you thinking, Hunt, honestly?) which was on my wall for five years when I was a student and has been hidden away in a private collection for the entire span of my life. Rossetti modeled for the hero, hence the flying saucer eyes and the my-uncle-knew-Lord-Byron-actually hair. That’s Millais, dead on the ironing board. If I can get a long, clear look at it, I’ll be happy for years.

How will you celebrate PRB Day? Catch me on Twitter and vote for your favourite painting using #PRBday. I will be baking a cake in honour of great art.

Is there anything better than perusing glossy photographs of artificial limbs and trepanned skulls over one’s breakfast? I think you’ll find there isn’t.

This week, I won a copy of the Wellcome Collection’s brand new ‘Guide For The Incurably Curious’.

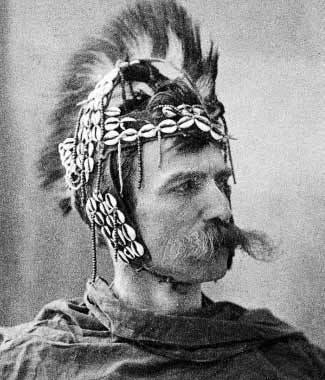

Wellcome is my favourite museum. If you have the slightest interest in wunderkammer, it’s a playground. The perfect balance of the medical, the historical, the scientific and the artistic, lovingly founded by Victorian philanthropist Henry Wellcome. Look upon his facial hair and tremble.

I’ve spent birthdays there, handling live leeches and drinking gin. I’ve seen Mexican miracle paintings there, verdigris mediaeval skeletons, and glass acorns for warding off lightning strikes. Once, an attendant saw how excited my friends and I were and fetched us goodie bags complete with wearable cardboard moustaches.

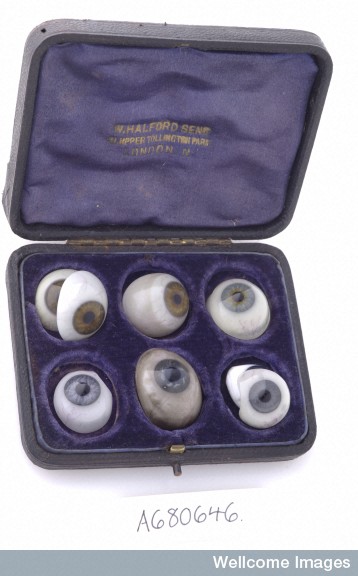

Science museums can feel unfriendly to artsy types, but at the Wellcome, the two disciplines interact. Upstairs, in the cool white Medicine Now room, slides of organs are displayed alongside barmy art (there’s a giant purple jellybaby as a metaphor for human cloning). Downstairs, in the darker, more anthropological Medicine Man room, you’ll find a wall of antique forceps and some beautifully detailed glass eyes which could easily be items of jewellery or sculpture. Plus, there’s a Bosch painting, and everyone loves a good Bosch.

But I think what I love the most about the Wellcome Collection is that, in a manner of speaking, I’m in it.

I have Marfan syndrome. The National Marfan Foundation explains:

Marfan syndrome is a disorder of the connective tissue.

Connective tissue holds all parts of the body together and helps control how the body grows. Because connective tissue is found throughout the body, Marfan syndrome features can occur in many different parts of the body.

Marfan syndrome features are most often found in the heart, blood vessels, bones, joints, and eyes. Sometimes the lungs and skin are also affected. Marfan syndrome does not affect intelligence.

Specifically, Marfans is caused by a kink in the fifteenth chromosome. So imagine the surreal excitement I felt when I turned a corner in the Wellcome Collection and came across this:

There it is. The Human Genome Project, chapter 15, subheading ‘Verity’s Wonky Genes’. I took it from the shelf with both hands. Buried amongst the reams and reams of baffling code inside was the string of glyphs that spelled out Marfan Syndrome.

Only one in five-thousand people have Marfans. The syndrome will generally make you around six feet tall and willowy in build, with exceptionally long, spidery fingers and toes. You may have a curvature of the spine or an uneven ribcage, and you can probably bend your thumbs into strange angles. Abraham Lincoln probably had it, as did Jonathan Larson, Joey Ramone, and, I strongly suspect, Lux Interior of The Cramps.

Marfans can affect you in all sorts of strange, annoying, sometimes life-threatening ways. Individual Marfs differ. As for me, I’m well looked-after by good doctors. I pace myself, I watch my diet and try not to be a stubborn ass when it comes to clinging to the barrier at Morrissey concerts or vigorous charity shopping the weekend after minor heart surgery. (Although holding hands with Morrissey and acquiring an antique nursing chair for £10 were worth the resulting drama).

One of the things about having an unusual health problem is that you can end up feeling alienated. That’s why I love the Wellcome Collection. Things that could be clinical or morbid, like Jennifer Sutton viewing her old heart after her successful transplant, are greeted with curiosity and joy.

It’s an ambition of mine to get Marfans into the Wellcome more prominently. Short of standing in the entrance hall with a sign on me, I don’t know how to raise awareness. I’m not quite ready to donate my hands. But it’s a syndrome that really lends itself to art. Maybe I can use my nonexistent artistic ability to chop up my MRIs in a nice lightbox, or draw an Edward Gorey-esque bunch of spidery fingers. Or, better still, persuade someone who actually knows what they’re doing to put Marfans in front of the lens, like Alexa Wright’s ‘After Image’ series.

Where’s an artist when you need one?