There’s been a ripple through the Marfan community this week. Some American comedians I’ve vaguely heard of (my world is muffled by nineteenth century poet’s letters to their dentists) have taken it upon themselves to mention Marfan syndrome in their latest film, The Internship.

Instead of using their immense media power to spread lifesaving information to the suspected thousands of people who don’t know they have Marfans, Vince Vaughn and Will Ferrell decided it would be easier to throw this out there, apropos of nothing:

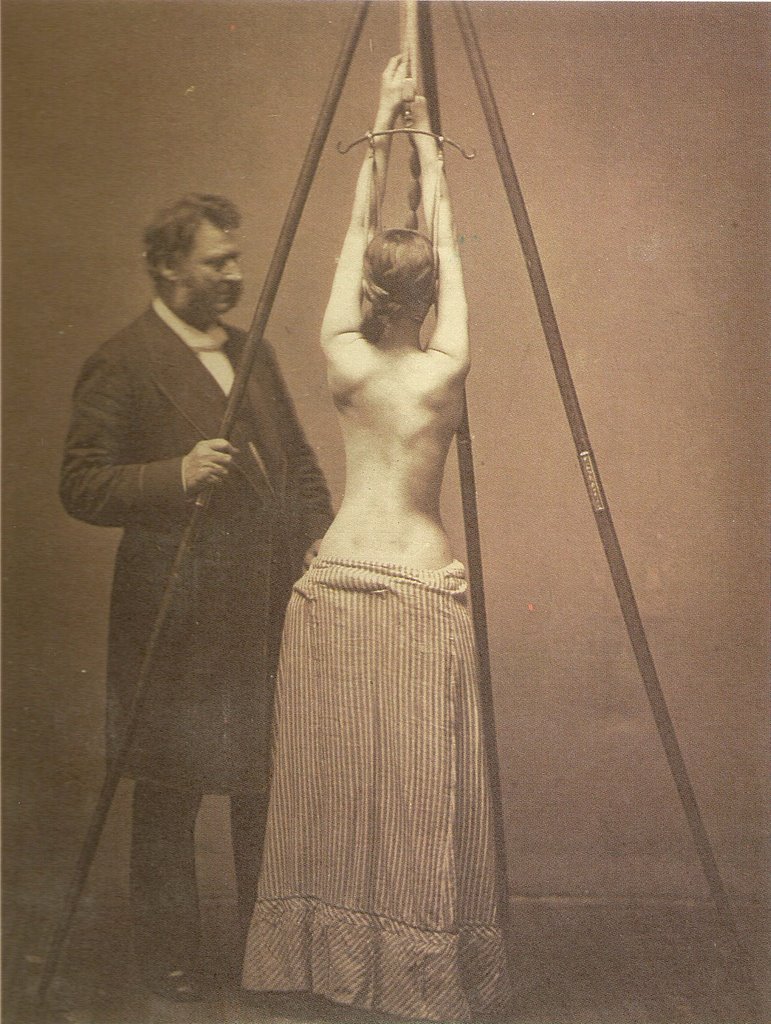

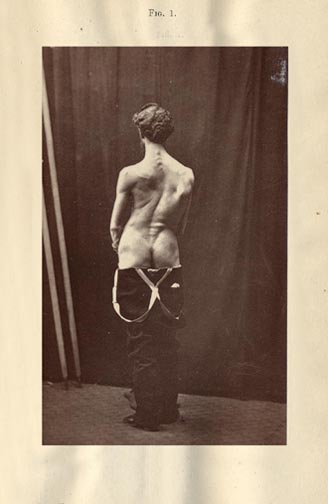

Will Ferrell: not actually qualified to take your ECG.

“C’mon, Marfan syndrome. You know, Marfan. Big man’s-disease. Giant killer.”

It’s crass, unfunny, and worst of all, untrue.

The National Marfan Foundation have released a statement urging the film’s producers to use this opportunity to spread the word about this often fatal disorder, and also pointing out the obvious: it was a stupid thing to say. Reactions from individual Marfs have ranged from “I’ve heard worse” to this, which reads like a punch in the gut:

A Virginia man, who lost his two-year-old son to Marfan syndrome in 2011, wrote that he was “extremely upset with the lack of taste, concern and respect concerning this disorder.”

The blogger Maya, also known as MarfMom, is, as always, joyful and positive, and has written about the film. She rightly thinks we ought to use this opportunity to educate, because the danger of the line is that it spreads misinformation. Half of people with Marfans don’t know they’ve got it. They go without medication, take part in dangerous activities, and may not find out until they’re in the back of an ambulance. Accurate information in the public eye is vital.

‘Big man’s disease’? Marfan syndrome affects men and women equally. ‘Giant killer’? Not all Marfs are exceptionally tall, and even so, they tend to be thin or unmuscular. In fact, if I had to pick a mythical creature to represent Marfans, it would be the willowy elves from Lord of The Rings. They’re long, they’re languid, and they’re sick to the back teeth of orcs crawling out of the woodwork. And what is this ableist obsession with fantasy monikers anyway? Giants, dwarves, monsters. Anything but human.

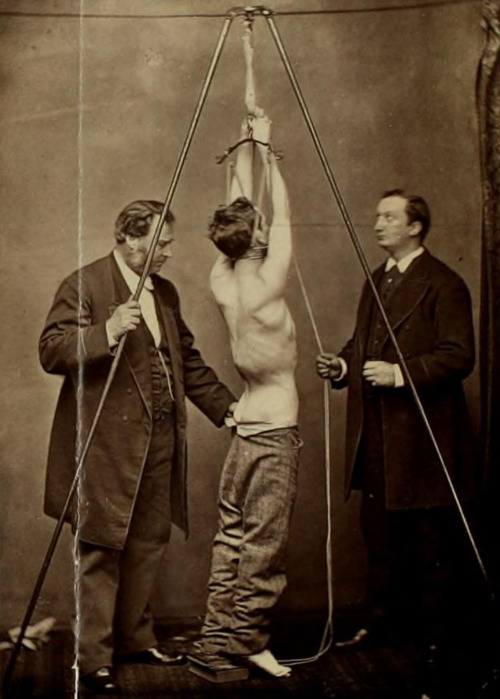

Elfking Thranduil thinks your attitude stinks.

Handy rule of thumb: If you don’t have a disability, don’t make jokes about it.

I’m going to have that printed on little glitzy flashcards to make it all the more memorable, because although it’s basic human decency, some people still struggle with it.

No.

All the Marfs I know make light of our health among ourselves, our friends, and families. Laughter is useful, particularly when – and this actually happened to me – a saleswoman earnestly informs you your incurable illness will clear up if you just drink enough aloe vera juice.

But if you don’t inhabit that sphere, you can’t assume what people’s thresholds are. You can’t assume what people are just about managing to cope with, what their history is, who they’ve lost.

Another thing Vaughn and Ferrell might be unaware of is that people with a long-term health conditions are strongly encouraged to keep their feelings to themselves. Classic derailing: “It’s only a joke, don’t take it so personally, no-one will take you seriously when you’re angry”. If you’re going to speak out about ableism you must cloak yourself in charm and detachment, as if this wasn’t your everyday life being discussed. Heaven forbid you become one of those frightening party-pooper militants who lurk in drains with Pennywise the clown.

Yes, it’s just a weak joke in a film unlikely to go down in cinematic history. But there will be kids who’ll suffer in school because of this. There will be adults who’ve lost a child or a parent or a friend who will have to smile politely at jokes like this from colleagues, strangers, and even friends who, because they’ve seen it in a mainstream film, think it’s harmless behaviour.

It isn’t.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

Sweating and dusty, we staggered outside into the rain.

![Epitaph for Happiness (and Audrey) There’s not one curse or evil deed, No spells or promises to heed, There is no equal power within the mind Yes! Love’s happiness was hard to find [April, 1969]](http://verityholloway.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/canehillpoem.jpg)

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

And spectacle is what the V&A provides, introducing you to the sensibly-suited Bromley boy who “just wanted to be known” all the way through to a cavern of screens displaying a gigantic gyrating Bowie flanked by mannequins displaying a career’s worth of costumes. The effect is like entering the temple of a strange, glamorous god, compounded by signs reading “David Bowie is watching you”. (We liked the less-worrying Warholian “David Bowie is thirsty – head to the cafe for orange juice or coffee!”) Would museum-goers accept such a gargantuan display from anyone else?

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.

This knitted catsuit was apparently available in pattern form for early fans to copy. Sadly no photos of valiant DIY efforts.