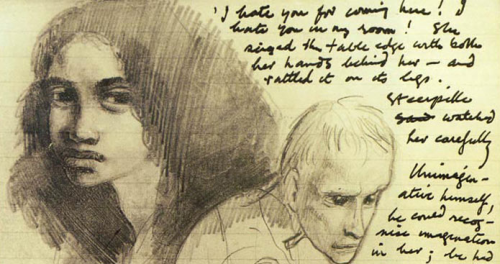

One of the pleasures to be had from Pre-Raphaelite artworks is spotting the cameo appearances: Millais lying on an ironing board, Fred Stephens ignoring the fairies, or Lizzie Siddal’s hair on Jesus’ head… It’s fascinating to see the individual artists’ stamp on a set of familiar features.

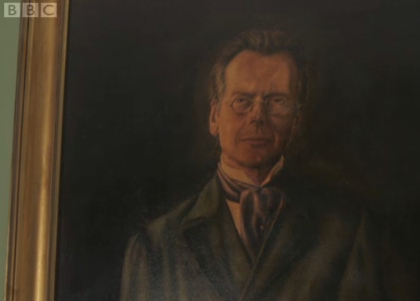

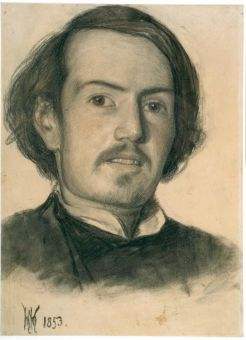

Despite being a compulsive fidget, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was, according to William Holman Hunt, a ‘good-natured’ sitter. His Italianate features appear in many PRB works, and likenesses of him, from sketches dashed off in chop houses to carefully-rendered portraits, often provide an interesting insight into the dynamic of the group at the time.

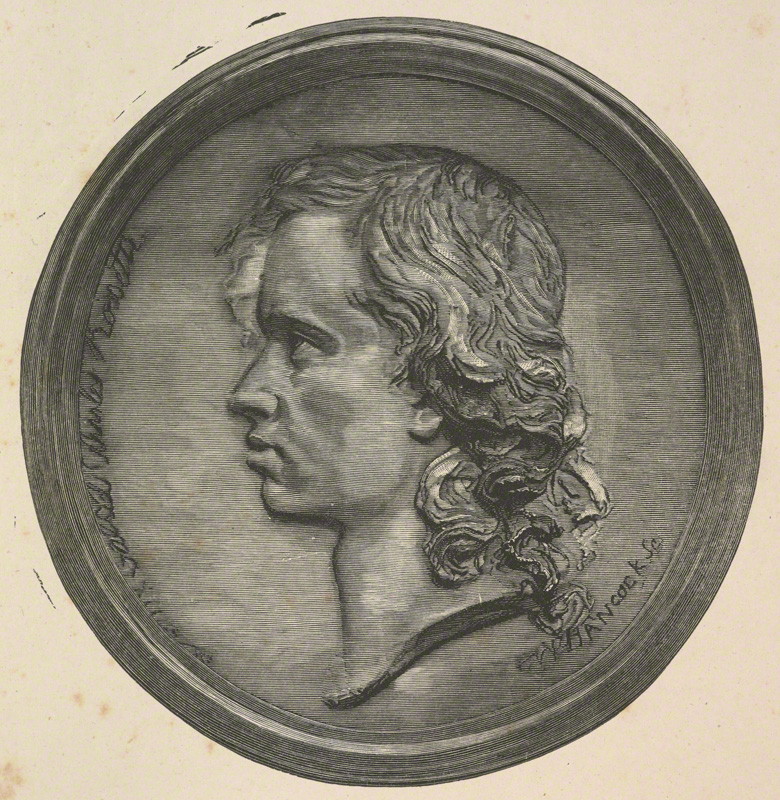

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

John Hancock (not to be confused with the American periwig enthusiast) is one of those fleeting blips on the radar of PRB history. From the glimpses we get of Hancock, it seems he was one of the many little fishes swept up by Gabriel’s net of enthusiasm. (Everyone was a stunning painter! Even if he’d never touched a brush.) Hancock’s young cousin Tom was certainly bewitched by this long-haired teenager bursting with admiration for Shelley and Keats. “How much I owe to listening to his talk at a very impressionable age,” he later wrote.

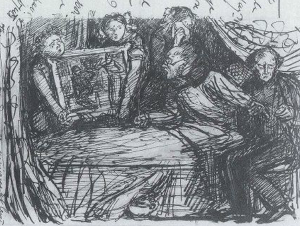

Like everyone else Gabriel was fond of, Hancock received a ribbing in verse. Here he is, getting on everyone’s nerves at a PRB gathering:

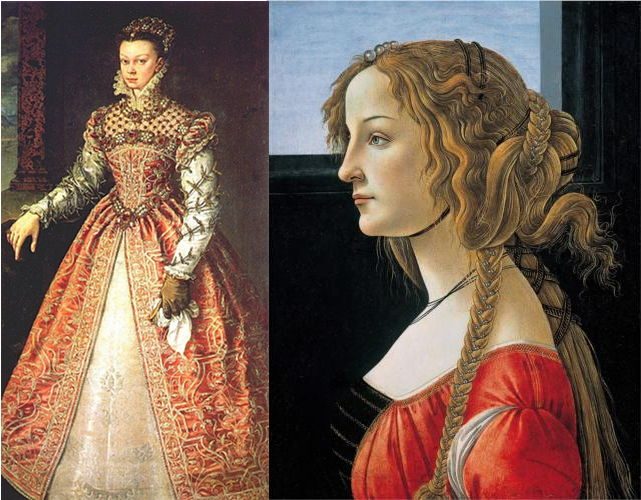

Dante’s Beatrice by John Hancock

The hop-shop is shut up: the night doth wear.

Here, early, Collinson this evening fell

“Into the gulfs of sleep”; and Deverell

Has turned upon the pivot of his chair

The whole of this night long; and Hancock there

Has laboured to repeat, in accents screechy,

“Guardami ben, ben son, ben son Beatrice”;

And Bernhard Smith still beamed, serene and square.

By eight, the coffee was all drunk. At nine

We gave the cat some milk. Our talk did shelve,

Ere ten, to gasps and stupor. Helpless grief

Made, towards eleven, my inmost spirit pine,

Knowing North’s hour. And Hancock, hard on twelve,

Showed an engraving of his bas-relief.

(Rhyming ‘screechy’ with ‘Bay-ah-tree-chi’ – amazing. Almost as good as ‘wombat’ with ‘flings a bomb at’.)

But not everyone took to Hancock. Gabriel’s brother William described him as ‘an ungainly little man, wizened, with a long thin nose and squeaky voice’. Such venom was possibly because he failed to produce promised funding and content for The Germ. It certainly wasn’t the last time William took the hump with someone who encroached upon his and Gabriel’s twin-like bond – see Lizzie Siddal, Fanny Cornforth etc – but, tantalisingly, we don’t have details.

Unlike the majority of the PRB circle, Hancock had steady financial backing from his family and experienced early success, exhibiting successfully in London and Paris and gaining widespread praise for his lovely plaster statue of Dante’s Beatrice. But something, somewhere, went wrong.

Hancock died of gastric irritation and exhaustion just after Christmas 1869, aged only 41, with just £20 to his name (very roughly, £1400 of today’s money). In his obituary, The Athenaeum lamented: ‘the anticipated progress of the sculptor was somewhat suddenly stayed and not renewed’. We do know that Hancock asked to use the PRB initials, but, for unknown reasons, was never permitted to do so. William alluded to ‘unfortunate circumstances into which it is not my affair to enter’ (but apparently enough of his affair to draw everyone’s attention to in print).

What happened to Hancock between the lovely plaster medallion of the teenage Gabriel and his early death? I’d love to know.

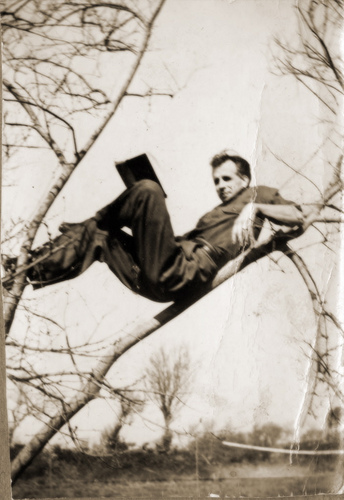

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

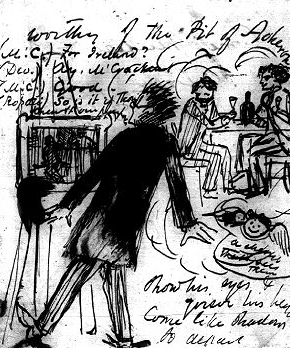

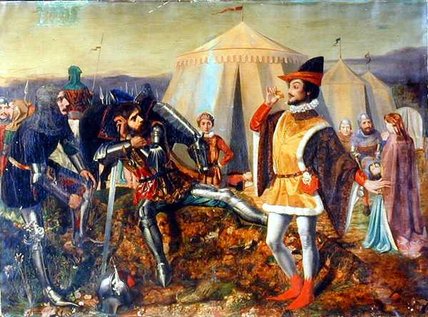

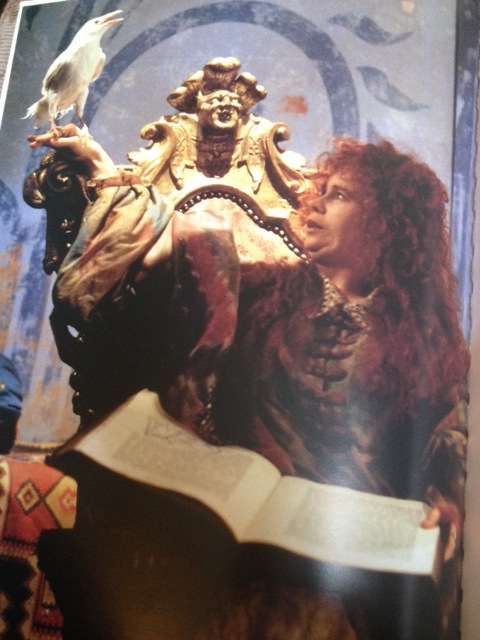

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”. Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.

Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.