August 2015 is when you can buy my novella of magic and makeup, crypts and clownfish.

It’ll be available in paperback and ebook formats, and can be found in those bricks-and-mortar bookshops you used to see everywhere, as well as online.

My magical realist novella, Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs, will be published in paperback and ebook formats later this year.

“Once we looked to earthquakes to gauge the mood of God. I mean, I’ve seen some sights since the fourth century… but lately things have taken a creative turn.”

More details to follow, but here’s some blurb to tide you over…

Saint Silvan is a miracle. Since he died two thousand years ago, not one atom of his beautiful body has succumbed to the natural decay of the flesh. But the planet is not so fortunate. In a small church in Croatia’s Dubrovnik, Silvan lies in state for the veneration of the faithful while nation after nation succumbs to the rising tides of climate change. When an immortal dandy calling himself Az offers Silvan a job boosting humanity’s morale by prettifying the revered dead, Silvan is eager to offer his talents, unaware that someone may be playing him for a holy fool.

From Imperial Rome to Soviet Russia, Silvan crosses the worlds of the living and the dead to uncover his past and divine his future in a dying world.

This is a story of magic and makeup, crypts and clownfish.

The Watchmaker’s Gift

I returned from midnight Mass eager for the warmth of my master’s hearth and something indulgent to drink. I had enjoyed the Christmas service, on the whole, but I was saddened my master was too unwell to accompany me as he had for many years. I was a small boy when he selected me as an apprentice, appreciating the slender dexterity of my fingers, naturally suited to the intricate arts of the watchmaker. Since then, his astounding miniature creations had earned us both considerable fame – timepieces no bigger than buttons, working clocks for dolls’ houses, and even a jewelled ring that chimed on the hour and was rumoured to have been purchased for a Russian princess. With his advancing age, my master’s mounting obsession to create the tiniest watch imaginable had claimed his eyesight. Now, even with his thick spectacles, he struggled to see so much as his own knife and fork when I served him supper. It pained him, and at church that Christmas Eve I said a prayer to all the saints I knew:

“Return my master’s sight to him, even just for the night. Help him craft one more tiny, wondrous thing.”

When I returned to our home above the workshop, I found only one candle lit beside our diminutive Christmas tree. My master sat in the gloom. I could barely ascertain the glint of his spectacles. The dark was bad for his eyes and the cold bad for his chest, but I hadn’t the heart to scold him, particularly when I noticed, next to the tree, an enormous box. It was wrapped in red paper and sealed with a ribbon of gold, and was almost as tall as me. It had not been there when I left.

“A small token, dear boy,” I heard my master say, from the shadows. “Unwrap it, please. It is past midnight, after all.”

With a glimmer of childish pleasure, I set about opening my gift. As I tore through the red paper, thinking I would find some large wooden chest or armchair, I was surprised to find neither of these things, but another layer of wrapping.

“Smaller,” he chuckled. I smiled, heartened by the return of my master’s good humour, and continued to unwrap my gift. Yet I found only another layer of paper.

“Smaller,” said my master.

After some time and much bemusement, I was surrounded by mounds of discarded red paper. The package had shrunk to the size of a shoebox, but I was no closer to my gift.

“This must have taken you hours to wrap,” I laughed. How had he hidden something so large from me? Our workshop was modest, our rooms above intimate. I knew of no-one with sufficient humour to help him in such a task. I was the only family the old man had.

“Smaller,” my master coaxed from the darkness.

Dawn approached. My head swam with my need to sleep, and the gift, still neatly wrapped, was now small enough to hold in my palm. I was irritated with him, and annoyed at my own pettiness in the face of such an elaborate and no doubt well-intentioned joke, but still I tore through layer upon layer of paper and ribbon. My fingertips grew sore. My eyes ached with the lack of light, and for another hour the only sounds in the room were the tearing of paper and the soft, infuriating laughter of my master.

“Smaller.”

When the gift was the size of my thumbnail, I thought that surely, at last, I was close. It would be one of his miniature timepieces, the smallest yet, a wonder of the age. My prayer would have been answered. We would share a brandy and chuckle at my astonishment, and in the light of Christmas Morning we would eat fruitcake and play cards as we had together since I was a boy.

Yet as I peeled back the final layer of paper, no bigger than a postage stamp, I found the package to contain nothing.

At first, I simply stared. My hands shook. There was no miniature timepiece, no gift, not even so much as a grain of rice for my labours. And my master, not a cruel man, not a man given to spiteful gestures, was laughing in his chair, in the corner, in the darkness. Laughing at me.

I snatched up the candlestick and strode with it to his chair to demand an explanation, to touch his brow for signs of sickness, or worse, some brain fever brought on by frustration and old age. I lifted the candle above my head to better view him and was about to open my mouth, unable to contain my annoyance any longer.

He had, for some considerable time, been dead.

It’s been a good couple of months for writing. After getting some lovely responses over my last short story (it’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize – I got the news in the middle of the night during a bout of chronic pain, and I initially thought it was my medication playing tricks) I’ve been putting concerted effort into finishing the novella that’s been lingering about since last winter. To be annoyingly vague, it concerns the nocturnal lives of mannequins, so, for a bit of research and a break from my desk, I visited Silent Partners at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum.

“Silent Partners is a ground-breaking exhibition devoted to the artist’s mannequin, that uncovers its playful, uncanny – and sometimes disturbing – history from the Renaissance to the present-day.”

The exhibition is far bigger than I anticipated. Three large rooms of artists’ lay figures, anatomists’ models, and fashion clotheshorses charting the evolution of the human simulacrum from religious devotion to arch Surrealism, along with striking photography and disembodied limbs dotted around the rest of the Fitz.

Life-sized dolls, no matter how beautifully made, are creepy, and the curators understand. From the moment you enter Silent Partners, you’re hit by the ‘uncanny valley’ effect. Viewing Walter Sickert’s life-sized wooden lay figure – laid out in a coffin, no less – I realised I was experiencing the same sensation of voyeurism I get when viewing Egyptian mummies or one of Doctor Gunther’s anonymous corpses. CT scans add to that sense of the uncanny. The mannequins once had life and purpose. Now they lie still.

To my perverse delight, the Fitz has sourced one of Thomas Edison’s horrendous talking dolls. It’s about as adorable as a vocal manifestation in a poltergeist haunting. The business went bust in the 1890s because children were understandably terrified. Dolls – blonde and smiling or otherwise – have the power to scare, whether you want them to or not.

Are you still with me after that?

Less unnerving is the lay figure’s role as studio companion. Many of the nineteenth century mannequins on display have small, faintly smiling faces and eyes that look submissively up from under the lashes as if to say, “…master?” This of course led to accusations of fetishism – a new term in fin-de-siecle psychology. After all, an artist’s lay figure is an idealised, usually female figure, posable, silent, and always there. A kind of sexless mistress, lifelike but lifeless.

Less unnerving is the lay figure’s role as studio companion. Many of the nineteenth century mannequins on display have small, faintly smiling faces and eyes that look submissively up from under the lashes as if to say, “…master?” This of course led to accusations of fetishism – a new term in fin-de-siecle psychology. After all, an artist’s lay figure is an idealised, usually female figure, posable, silent, and always there. A kind of sexless mistress, lifelike but lifeless.

Edward Burne-Jones bears the brunt of this. Comparing his Pygmalion series to the vibrant new woman of Jones’ time, one label points to Ned’s fixation with statue-serene models as a symptom of his own sexual repression. That strikes me as a bit harsh, particularly when looking at his famously fiery lover, Maria Zambaco. You don’t roll around on the cobblestones with someone if you’re not at least slightly open to the urgency of your own passions. But I see what they’re getting at: ‘I love you, but please stand still and shut up’.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

There’s a surprising amount of Pre-Raphaelite art, considering the movement was so concerned with realism. Ford Madox Brown owned five lay figures at the time of his death (including a horse), and The Last of England was completed partially with the help of these figures. Critics noticed. There’s a fun insult from the eighteenth century: “This painting stinks of the mannequin”. Millais was better at hiding his use of lay figures. The Black Brunswicker required two so that the models – Dickens’ daughter Katy and an army private not of her acquaintance – wouldn’t have to hold such an intimate pose.

The fashion segment was particularly interesting. Earlier clothes modelling mannequins have far more physical agency than the ones you’ll see in Topshop windows. These eighteenth century lifeless girls have hands that reach and gesticulate, and faces poised as if to speak. It was only in the nineteenth century that shop windows began to display disembodied hips and busts. A decline in tailoring to the individual? Or a less sinister preference for cheap mass production?

Overall, Silent Partners is an impressive undertaking and hugely interesting – and free! I’ll be returning at least once. The only downside was the lack of labels on the large photographs dotted around the other galleries, because I loved them but couldn’t find the photographer’s name. It’s probably my shortsightedness, but somebody enlighten me, please.

Silent Partners is on at the Fitzwilliam Museum of Cambridge until the 25th Jan 2015, and then the Musée Bourdelle in Paris from the 31st March until the 12th of July 2015.

My short story, Cremating Imelda, is published in Animal Literary Magazine this month. Imelda, a modern hermit in an abandoned village on the Norfolk coast, is a woman with a morbid talent concerning food – and mortal sin.

This is an old fascination of mine: the links between death, what we eat, and why.

For centuries, sin-eating was a funerary tradition grudgingly tolerated by The Church. Usually a reviled individual on the edge of society, the sin-eater went to funerals and ate bread or cake off the coffin, absorbing the deceased’s sins and thus allowing them to speed through purgatory. Presumably, they hoped someone would do the same for them, when the time came.

Sin-eating has long fallen out of favour. But there are more recent funerary traditions involving food that still manage to make us uncomfortable. A childhood memory: a Greek holiday. I was permitted one treat; anything I chose from the bakery. This bakery was nothing like the ones in England. There wasn’t a single stodgy pink bun or unhappy gingerbread man. Every confection was a miniature ornament sprinkled with green pistachio, or shining with honey. But what I wanted was inside a glass cabinet. A dish piled with plain brown biscuits. Just flat brown rounds of dough – nothing to excite a child. Perhaps it was because they were behind glass and therefore forbidden. I knew what I wanted, and I asked for it.

“Those are not for little girls. Those are for… for…” The baker wheeled her hands, searching for the English. “The funeral.”

Get the child away from the death biscuits. This was a Greek custom, the baker told us. Sweets to eat in the presence of the dead. Looking at the mountain of biscuits, I remember thinking the locals must have been dropping like flies. I ended up with some unmemorable cake or other, and the episode went down as further proof that Verity always was ‘a grimly kid’ (to borrow Rossetti’s phrase). But the idea of funeral biscuits fascinated me. Why didn’t we do this in England?

Food has become the awkward aftermath of the funeral service. I find myself in church hall kitchenettes, spending a great deal of time nibbling dismal supermarket own-brand Jammie Dodgers because it gets me out of talking to anyone. I’ve already stipulated I want gin served at my funeral, partly because everyone secretly hates those undersized cafeteria cups of tea, and also because I think a funeral is a place for a sort of human communion. “Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me.”

The Nourishing Death blog is a brilliant resource for anyone interested in the ways people all over the world honour their dead with food. Because food, in a ritual setting, is communication. In Funeral Festivals in America, Jacqueline S. Thursby writes of the funeral biscuit’s role in the Victorian way of death in the USA’s Pennsylvania:

…a prevailing funeral custom was that a young man and young woman would stand on either side of a path that led from the church house to the cemetery. The young woman held a tray of funeral biscuits and sweet cakes; the young man carried a tray of spirits and a cup. As mourners passed by, they received a sweet from the maiden and a sip of spirits from the cup furnished by the young man. A secular communion of sorts, these were ritual behaviors that transcended countries of origin and melded a diverse young nation with the common cords of death, mourning, and tradition. The funeral biscuit served as part of a code representing understood messages of mourning, honor, and remembrance.

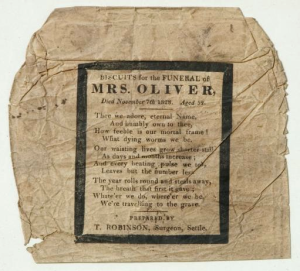

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

All flesh is grass. Enjoy your biscuit.

It’s little wonder such unflinching morbidity is unwelcome in the sanitised funerals of the modern world. But many European cultures still hold on to the funeral biscuit. In 2011, a Greek family were accidentally fed cocaine-sprinkled funeral biscuits, leading to what sounds like a lovely service:

The elderly bystanders, instead of mourning, began to dance around the dead, and the tears turned to nervous laughter. The cognac was consumed in shots accompanied by the sound of happy toasts, and there were some who started ordering mojito cocktails.

So what do you have planned for your send-off? If you could have a sin-eater come to wipe away your deeds, would you?

My short story, Cremating Imelda, is the featured story in this month’s Animal Literary Magazine. When Imelda’s 440lb body overwhelms a crematorium’s ventilation system, the newspapers are equally horrified and amused. But Imelda had a life before her cremation, and a secret talent only her parish priest was privy to.

Also out soon in the Pre-Raphaelite Society Review is my article ‘In Defence of Walter Deverell’. Sometimes referred to as the ‘lost’ Pre-Raphaelite, Deverell died before his talent could truly take off. What happened to his family – and how they kept Walter’s place in PRB history alive – was interesting and poignant to research. Some typically bitchy Victorian letter-writing, too, with what appears to be the use of some rather sneaky pseudonyms.

I find I’m writing more and more about a sense of place. I’m moving house this week, and all my notes are about waterways, familiar food, and the colour of soil.

I was born on the Rock of Gibraltar. My Dad was stationed at the Navy base there, and I spent the first two years of my life beautifully oblivious to the existence of England and drizzle and Margaret Thatcher. I went back last month, not for the first time. As usual, didn’t want to return.

As a Forces child, going wherever the MOD tells you to while the head of your family sweats in a minesweeper’s engine room somewhere far-off and unpronounceable, you’re left feeling like you belong nowhere. Family interactions take place via satellite phone, friendships are brief, and your birthday plans depend on what Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Miloševic have in store for June. Though I left Gibraltar in the late ’80s, the place always meant more to me than anywhere that followed. Two years after Gib, we were on a godawful submarine base in Scotland. Our allotted house had been arsoned a few months previously. Shards of glass, all over the garden.

The Rock was stable, I was safe there, and it was mine. Nulli Expugnabilis Hosti.

Gib is dusty and colourful and intimate and huge, and every time I get off the plane and crane my neck to see the gulls wheeling around the harsh green crags of the upper Rock, I wonder why I ever let myself get mired in the flat Fens – though I love those, too.

It’s the abundance of light and water.

Plus, you can buy a litre of vodka for £3.99. If that were the case in Britain, you’d be stepping over mounds of poisoned teenagers, but the closest I got to an encounter with a drunk was a sober gentleman carrying an easel, wanting to tell me something important:

“You’ve changed your dress. You were wearing black this morning. I saw you, wearing black. I had a demon inside me for fourteen years. But I met a man from Birmingham, and he made it come out of my neck, like whoosh.”

I find it’s only after you leave a place that you begin to feel it inside you.

My sonnet ‘Kelmscott’ has been published today in The Pre-Raphaelite Society’s annual poetry competition anthology.

“Collected in this book are the entries to the second Pre-Raphaelite Society Poetry Competition. The poems offer a myriad of pleasantly surprising responses to the Pre-Raphaelites, their successors, paintings, poetry and lives.”

Copies are £3.99 from lulu.com.

A belated happy new year to you all. 2013 brought new friends, new skills, and new publications, but I’d be fibbing if I said I wasn’t ready to leap into 2014.

I’ve made headway on a new, inevitably Victorian novel. This was aided in part by my summer experience at the Isle of Wight steam railway, getting to grips with the challenges of hopping on and off steam engines in a crinoline during the hottest weekend of the year. There’s nothing like primary research.

Getting intimate with a new narrator is part joy, part daunting challenge. Emma Darwin’s post, 19 Questions To Ask (and ask again) On Voice, has been a helpful point of focus as I reign in the material of the woolly winter months.

“Yes, Voice, overall, is one of the archetypal writerly things that you can’t, completely, make happen by sheer force of will. But as I was discussing here, it’s a mistake to assume that the only good decisions are those which come from that mysterious place we call instinct and intuition. A bit of clear thinking and precise focus can make things clear for your intuition to recognise. And besides, there are always times in your writing life – the depressed moments, the hungover and lack-of-sleep moments – when intuition fails you. But even then, you can always ask practical, technical questions about language and grammar, and – as I was exploring here – so often when you do get practical and technical, you’re led back to the strange, instinctive stuff of our imagined worlds.”

I spent the Christmas break reading Donna Tartt’s The Little Friend and goggling at her masterful world-building. I’ve never been to Mississippi, but, 500 pages later, I feel I know something of its dreary gorgeousness and savagery. “Oh man, you are starting with the wrong Donna Tartt novel,” says just about everyone I mention it to. If that’s Tartt at her worst, I’m intimidated by the possibility of her best.

Which brings me to my resolution. I don’t usually make resolutions. I find myself struggling to think of a suitably righteous goal and become distracted by bizarre Victorian greetings cards encouraging the recipient to fire a pig out of a cannon for luck.

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on Literary Rejections, experience accumulates. I want to be more conscious of that this year. The practical, technical stuff as well as the strange and instinctive.

But, because I’m feeling disgustingly optimistic at present, my 2014 resolution is to keep striving, keep learning, and above all, as always, keep writing. Rossetti had a lifelong habit of trying to accomplish ‘something in some branch of work’ every day, whether that meant poetry, painting, translation or illustration, and when he wasn’t working – or when he was depressed and unable to work – he was reading, observing, taking things in. As I said on Literary Rejections, experience accumulates. I want to be more conscious of that this year. The practical, technical stuff as well as the strange and instinctive.

Failing that, during ‘the depressed moments, the hungover and lack-of-sleep moments’, I can fall back on my secondary resolution: wear more hats.

I’m on Literary Rejections, talking about my experience of the agent querying process.