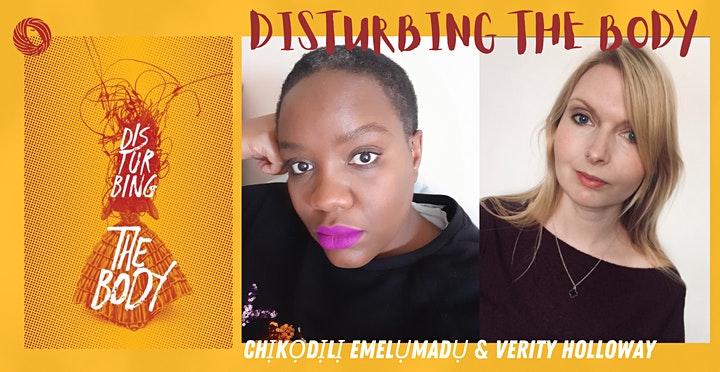

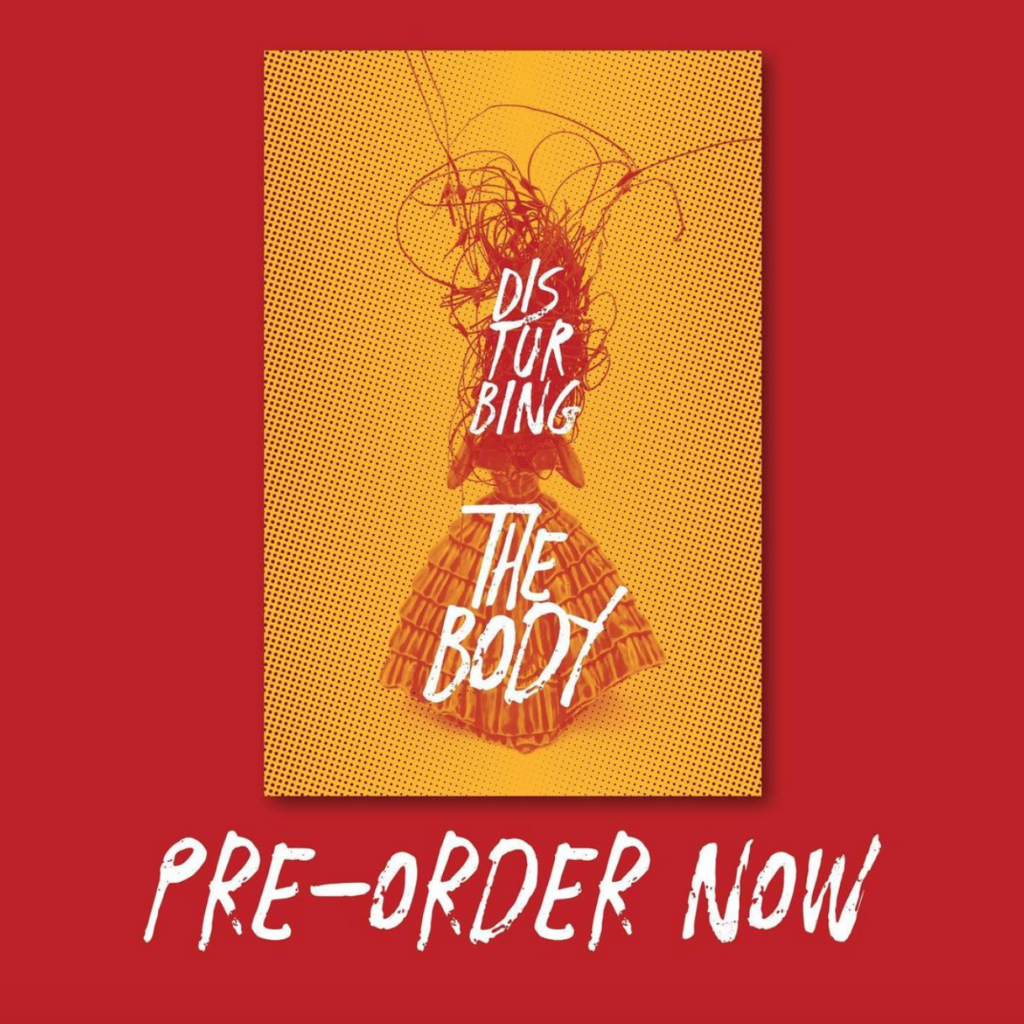

Join me and Chikodili Emelumadu on the 23rd of March for the online launch of Disturbing The Body. We’ll be talking disrupted bodies, subverting genre, and lots more.

Pre-order your copy here and make us all very happy.

Join me and Chikodili Emelumadu on the 23rd of March for the online launch of Disturbing The Body. We’ll be talking disrupted bodies, subverting genre, and lots more.

Pre-order your copy here and make us all very happy.

It’s Marfan syndrome awareness month, so it’s about time I finished this series, isn’t it? It’s been a long time since I last blogged about my aortic root replacement and bypass. That’ll be the pandemic. I was in the middle of my final stretch of cardiac rehab when the gyms were first closed, so that effectively put an end to my journey as an outpatient.

I was extraordinarily lucky to have elected to have my surgery in 2019. Any later, and I don’t know how any of it would have worked. I suspect I’d just wait until everything went back to normal, but as I write this – in February 2021 – that day still looks distant.

So. When I left you, I was on the ward, just about able to sit in the chair for an hour a day, in less pain than before, but still impossibly weak. Stage one rehab had begun – a slow walk to the end of the corridor every day, plus one stair if I felt like a challenge.

Something I wasn’t prepared for was losing the dexterity and strength in my hands, albeit temporarily. I couldn’t cope with mugs, so my nurses started giving me coffee in a toddler’s sippy cup. And frankly, being a giant, caffeinated baby was pretty great.

The other thing I wasn’t prepared for was the migraines. Within a few days of my surgery, I started experiencing bright lights in my vision, and eventually those bright lights became crippling headaches, stopping me from completing my all-important task of getting out of bed once a day. This would become the greatest obstacle of my recovery and the year that followed. I’ve done so much reading, visited a neurologist, and had my brain scanned, but still don’t know exactly what caused this. The good news is, I now only suffer one migraine a month. Daily magnesium is the only thing that has helped.

I was in hospital for a total of ten days. Most only stay for four after an operation like mine, but as I’ve said, I kept spiking fevers and they wanted to keep an eye on me. By day nine, my nurses were running out of viable veins to prick me in, and I discovered the extreme delight that is the eight inch cannula. No. Don’t Google it. This isn’t normal, but I have delicate vessels, and after heart surgery, there are only so many places left to try.

Would you believe, when the time came for me to leave, I was thoroughly institutionalised. The idea of shuffling out into the car park was like boarding a rocket to Mars. Trivial things frightened me – showers, doorsteps, kids running past me. I was a delicate piece of porcelain, a snail without a shell, painfully aware of my broken bones and bruised flesh.

I had to leave my ‘teddy’, my roll of towels, behind. I was scared of that thing in Pavlovian way. The word ‘teddy’ still makes me pause, being so attached to pain, but swapping it for a cushion from home felt strangely reckless. I’d need to carry a cushion for twelve weeks, for sneezing, standing, and rolling out of bed. Make sure yours is soft but firm, with no pointy buttons or zips.

Practical tips: when getting in and out of cars, sit on a blanket with two loose ends either side of you. If you get stuck in a sitting position – which you will – someone can hoist you. Sitting and getting up was my Rubicon, post-op. “She is risen!” I’d say, because every time I successfully stood without aid, it was cause for celebration. Whenever you have to go anywhere – and you’ll be swamped with outpatient appointments – take a thick cushion. Don’t be like me, unable to stand in a GP surgery, while a dozen OAPs look on in amusement. You are forbidden from using your arms to bear your own weight. Indeed, the temptation will be gone altogether. On my first trip out of the house, someone handed me a pint glass of water, and I stared at it in terror. Nothing heavier than a travel kettle full of water – that’s the rule.

After two weeks, my chest looked like this:

Surprisingly good! Puffy, bruised (note my green hand) but healing steadily.

Then, by six weeks:

For scar minimisation, I used a silicone treatment called ProSil, and it’s seems to have worked. My nurse warned me not to use Bio Oil – no clinical proof of it working, apparently, and if you use it too early it can do more harm than good. Don’t @ me, Big Bio Oil.

In that first month or so, my life was a limited one. Once an hour, I took a sedate walk around the garden. Very sedate. I got to know every blade of grass intimately. I slept all the time. I called them my Cataclysmic Death Naps, because I got a two minute warning and then I was just out. Gone. I’d wake up and think a week had passed. As for food, I was hungry, but only for green things. I craved salads and eggs. How boring. I drank kefir in the mornings, with fresh blueberries. And then there were the bananas. Bananas are good for bone metabolism, and as my bones were healing, I needed one a day. I forced down those yellow bastards. Sometimes it took me three hours. Yes, there were sweeties, too, and wine. You need some joy.

Exhaustion, effort, exhaustion. I learnt to budget my time. A brief shower would cost me an hour of rest, at least. Roll out of bed, no hands, recover. Stand up, recover. Dress without bending over, recover. I had a crate of books begging to be read and I touched maybe two of them in six weeks. Sitting was a trial, so I spent my evenings propped up by pillows in bed, managing one small sketch in a notebook and maybe half a chapter of a novel. All that time to myself, and no energy to enjoy it with!

I noticed my chest scar was becoming hard and bumpy. This is called ‘brawny tissue’ – scaffolding, effectively. It’s temporary, but a little alarming at first. The knot at the top of my sternotomy scar freaked me out the most. After a few weeks, the sharp end was threatening to piece my skin, and I phoned my nurse after a sleepless night, thinking the wires knitting my sternum together were breaking out, Alien-style. No. The knot never broke through, by the way, but it’s quite routine for them to do so, and a nurse will just snip it flat. After about three months, mine just went away. But you’re going to be jumpy about all sorts of small things. One time, the sound of a child bouncing a football was enough to make me say, “I have to go home”.

I was very anaemic. Considering I’d just been through a combine harvester, it wasn’t surprising. The anaemia, combined with a spike of pain in my back, put me back in hospital briefly. I was given iron pills rather than infusions, as my difficult veins weren’t behaving and in the end the nurses decided the stress of repeated attempts outweighed the benefit of instant iron.

So, pain. Enough to keep me awake some nights, but nothing like the pain in hospital. Ridges of muscle popped out from my back, spasms I couldn’t wriggle away from. I’m a side-sleeper, and that wouldn’t be safe to attempt until the twelve week mark. In truth, it took me nine months to sleep that way again. In the meantime, I was given good old diazepam to loosen my muscles and to make me care a little less. This, like all the post-op challenges, would fade away with time. None of this is permanent.

I began stage two rehab after my twelve weeks of sternal precautions were up. Rehab is optional, but if you want to get better, you’ll do it. Classes are 45 minutes long, usually at a local leisure centre, and everyone is a seventy year old man. I’m only mildly exaggerating – I was the only female until my final two classes, and the youngest by at least twenty years, but everyone was shyly friendly – feeling vulnerable, like me – and had a story to tell. Tough old boys who’d keeled over on golf courses, younger guys who’d lived a bit too hard. The exercises are simple, gentle, and last a minute each. A minute of gentle weight-lifting, a minute of walking, a minute with a resistance band, and so on. This will all seem daunting at first, but the nurses are constantly checking your pulse and oxygen. I usually spent the rest of the day in a Cataclysmic Death Nap, but rehab was a good experience for me. It gave me an excuse to buy this t-shirt, for instance:

I graduated rehab in the summer, seven months post-op. Got a little certificate and everything. Since April, I’d lost most of my muscles, my stamina was rock bottom, and my body felt like someone else’s. I was down about it sometimes, but that unhappiness was intermingled with awe at what I’d survived and each new milestone I was meeting. Some of these moments were hilarious. I once stood up faster than a ninety-year-old lady in a neighbouring chair and did an inward fist-pump. I learnt to pick socks off the floor with my feet and toss them into the air to catch. BBC’s sitcom Ghosts was the highlight of my week, but it hurt too much to laugh, so I’d try to hold it in, which only made it funnier. Being able to enjoy the absurdity is a real asset after something so massive.

Stage three rehab is voluntary, but I signed up anyway. It’s largely the same as stage two, only you do it alone, in a real gym, with a pulsometer and oxygen monitor on stand-by. I walked twenty minutes to get to the gym, worked out gently but determinedly for forty-five minutes, then walked home. Every Tuesday, I felt like Geralt of Rivia. Sometimes I didn’t even need a nap afterwards.

And then… 2020 happened. The gyms closed, I stayed at home, and any plans for a one-year anniversary party were shelved. But recovery didn’t stop. At twenty months, I found I could sleep on my left side again, hearing my heart loud and strong. My sternotomy scar is pale and flat. My ankle scar is invisible, and my bypass incision on my thigh is white and soft. Of my lung drains and pacemaker, three Xs remain, and at the base of my neck are two perfect white dots where the catheter entered. I love them all.

I want to thank everyone who got me through open heart surgery. Mister Nashef my surgeon, my whole surgical team (who I met but mostly can’t remember because drugs), all my hardworking nurses and therapists, the cheerful cleaners who chatted to me even when I was wittering rubbish, my rehab team and fellow zipper club members, my family, my friends, my partner, my gentle dog, and all the Internet heart veterans who held my hand virtually through the whole thing.

And now… back to life.

At last, pre-orders are open for Disturbing The Body! Throughout 2020, I worked with artist-psychologist Louise Kenward and Boudicca Press to put together this anthology of body-themed speculative autobiography by women.

From chronic illness to major operations, child-bearing to disability, Disturbing The Body sets out to explore the many ways women feel at odds with their own bodies. We encouraged our authors to embrace the weirdness of their perceptions, telling their truths with a truly individual eye. We’ve collected some breathtaking true stories by Chikodili Emelumadu, Abi Hynes, Natasha Kindred, Irenosen Okojie, and many more. I can’t wait to share them with you.

Get your copy by the 23rd of March from Lighthouse Bookshop, Edinburgh’s radical bookshop.

Cat’s out of the bag! The secret Yuletide edition of Hellebore landed. My piece, The Hauntings Of Cold Christmas, is among some very exciting company: Katy Soar, Jackie Bates, John Callow, John Reppion, Shane McCorristine, Roger Clarke, and Elizabeth Dearnley. Artwork by Blood and Dust, Eli John, and Nathaniel Winter-Hébert.

I was having WordPress issues over Christmas, hence this post is late, but as a festive treat I recorded a three-part reading of my ghost story Florabelle to my Patreon for $1 subscribers. A Victorian medical student picks a man’s pocket to pay off his gambling debts, only to find himself in the midst of a very active haunting…

Happy October, quaranteenies. You can now pre-order the Malefice edition of Hellebore zine, just in time for Samhain.

In The Akenham Devil, I uncover the Victorian tragedy that changed the English way of death forever. As always, I’m thrilled to be among such esteemed company as Catherine Spooner, Rebecca Baumann, Thomas Waters, Catherine Winter-Hébert and Finn Robinson, Thérèse Taylor, Maria J. Pérez Cuervo, and Colin J. McCracken.

Following the success of Disturbing the Beast, a collection of weird fiction stories by some of the best women writers in the UK, indie publisher Boudicca Press are crowdfunding for a new anthology of speculative memoir centred around experiences of mis-behaving bodies, from women and those who identify as women in the UK. The Kickstarter will launch on 15th May and they seek to raise £2300 to print the books, pay all the authors, editors, designers and book makers involved in the project.

The crowd funding campaign comes at a time when many businesses, bookshops and independent publishers are striving to survive the wide reaching effects of Covid-19. Boudicca Press hope that this campaign will ensure the fruition of a much deserving anthology and the fair pay of all involved.

The new anthology, Disturbing the Body, came to fruition when Verity Holloway, author of Pseudotooth, Beauty Secrets of the Martyrs and The Mighty Healer, approached Boudicca Press with a unique idea that she felt needed to be heard. Verity started writing about her perception of pain in intensive care following her experience with open-heart surgery. Tanked up on morphine, Verity met a lot of people who turned out not to be real, time was warped and she felt that the sense of her body completely changed. After speaking with Georgina Bruce of This House of Wounds and Louise Kenward, an artist and writer with a background in the NHS, working as a psychologist and psychotherapist, she discovered that they had all written creative non-fiction pieces in response to their unnerving experiences with their bodies. Verity says “It’s world changing, isn’t it, when your body goes out from under you? You see everything from a strange angle.”

Disturbing the Body explores body-horror themed creative nonfiction from women and those who identify as women of all ages in the UK. Body themes range from experiences with major operations, dealing with cancer, childbirth, chronic illness, disability, or any moment where a woman can feel powerless and out of the ordinary against her own body. Submissions were obtained through an open submission period, with Verity Holloway and Louise Kenward contributing their speculative memoirs stories.

The Kickstarter campaign to raise £2300 to fund the anthology will launch on Friday 15th May 2020 at 8am until Friday 12th June 2020 midnight. The book will be published by Boudicca Press in October 2020.

Time flies when you’re diligently attending rehab. It’s been more than eleven months since I had my aortic root replaced. I last blogged about my experience six months ago (what!), but time has been moving at a strange rate what with my improving levels of stamina and the increase of daily responsibilities that come with recovery. You feel like you’re on a plateau, when really you’re still marching up that hill.

I know you’re only here for sexy Instagram before and after shots, so…

When I left you, I was talking about my time on the Critical Care ward (ICU). No one in the history of human endeavour has ever said “Critical Care – fun for all the family!”, and I know if you’re reading this in anticipation of your own surgery, you’re likely not going to be expecting a spa experience. I’ll be honest – it was not fun. But. The worst thing by far was the inability to understand that what I was experiencing was temporary.

To recap – I’d just had my chest sawn in half and cracked open like a walnut. I had two significant leg wounds I wasn’t expecting. Entering my body just above my waist were two lung drains roughly the same thickness as tubes of Smarties. These were all surprising and new sensations I had no frame of reference for, and the first thing your brain does when faced with startling new stimulus is to think, This is my life now.

Everyone kept telling me, no, this is your life now.

For pain relief I was given oral morphine, codeine, and, hilariously, plain old paracetamol. None of this helped. I did not sleep. I couldn’t accept so much as a mouthful of food. I watched the nurses come and go in day and night shifts, on, off, on, off. Time lost all meaning. By day three I was… unhappy. I remember a group of doctors at the foot of my bed puzzling over my body’s refusal to accept pain relief.

“Do we use ketamine in this hospital?” one of them muttered.

God, I wish the answer had been yes.

Instead, I was given an epidural. When I try to describe this experience, my brain throws up a wall of static because this was… unenjoyable. It also turned out to be completely useless. In the end, I was given a personal morphine pump, which is a bit like an opiate vending machine where you just mash the button in the hope of blissful oblivion. None of this is normal, by the way, but in general the young do experience more pain than the old. I was just the lucky millionth customer.

I think it was day three when my drains came out. In the end, this was the only thing that gave me relief. With the help of my morphine pump and a canister of gas and air, I was perfectly happy for the nurses to just yank those suckers out. That’s literally how they do it. Two seconds of internal carpet burn and a couple of neat little stitches. Honestly, it was wonderful. The pain was by no means over, but I now had one less problem to live with.

Eventually a bed was found for me on a regular ward. I was profoundly full of morphine by this point, so I remember the trip down the hall as something akin to The Dam Busters complete with explosions and search lights. I just remember thinking This bed is moving too fast and they’re going to clip a door and I’m going to just die. It was the middle of the night, eerily quiet. When we arrived at the ward, I was given my own private room, which I would later understand as a blessing. At that moment, in my drug-addled brain, I’d been wheeled into an empty grey cell where I would be left to die. Everything equated death in my mind that night. That was the drugs talking.

A word on opiates – I started hallucinating wildly as soon as I left Critical Care. Some people experience this, others don’t. It was never frightening, but it was impossible to tell reality from dreams for at least two days, and even weeks afterwards I had to ask people I knew if they really had come into my room at night to stare wordlessly at me like Christopher Lee’s Dracula. It’s hard to tell yourself everything’s going to be okay when Madame Tussaud shuffles around your bed, hanging up death masks of Louis XVI.

From here, I’m happy to say, I improved daily. Bodies – even my delicate Marfanoid one – work fast to heal. I still couldn’t eat much, so the catering staff – who are perfect angels working under very strained circumstances – made me ice cream milkshakes to try to get calories into me. It took me entire afternoons to get half of one of these down me. Everything becomes an epic battle, but with an army of kind, hilarious nurses and healthcare assistants behind you every step of the way, the impossible becomes doable.

As I regained my grip on reality, I had to come to terms with how radically reality had changed. My usually dry skin had become incredibly oily. My hair – everywhere – had turned ginger and was growing at an amazing rate. My fingernails, too, were like stalactites. The nurses started calling me “That poor girl” because my period arrived out of nowhere. Swollen, sweating and covered in bruises, I resolutely ignored my chest wound. I’d been trussed up in a binder, so I was yet to see it, and even the thought turned my stomach. I’d spent a year on the waiting list worrying about how it would look, how much I would hate it, what a big deal strangers would make out of it.

Naturally, I glimpsed it by accident.

A nurse had removed my binder to wash me, and my eyes flickered open long enough to register a puffy yellow mass of bruises and iodine. I think I must have groaned because the nurse said, “It’s low down and very neat. I see a lot of these. This is a good one.”

Well, I thought. There’s nothing I can do about it ether way.

Every day, my task was to get out of bed at least once and sit in the chair. My room had a bathroom, but I couldn’t walk to it, as hard as I tried. I wanted to move. I also desperately wanted to stay in bed. It took two nurses to get me up and ease me back down every time. Sometimes, it was just impossible. That was the worst. Having to be told to give up. I can still hear my Nigerian night nurse telling me, “If you say sorry one more time, imma smack your bottom”.

But the trend was an upward one. Every day, I lost another tube. No more neck cannula, no more temporary pacemaker. One day I realised I could speak in short sentences without much trouble. Another day, my nurses walked me to the bathroom to brush my own teeth. Soon, it was time to have my first solo shower, perched on a stool. I felt like a gladiator. My appetite came roaring back, and though I couldn’t realistically eat much at all, it was all I could think about. If you’d offered me a Dorito, I’d have bitten your arm off. That’s your body healing – urges become commands. Eat. Sleep. Eat more. Sleep again. OBEY.

I was in hospital for a total of ten days. Usually, someone undergoing an aortic root replacement will be sent home on day four, but I was spiking mysterious fevers every evening and needed antibiotic fusions. It turned out I had antibiotic resistant bacteria on my lungs. This sounds horrifying, but it wasn’t the same thing as having an infection, so I used the extra time to work with my physiotherapist, learning to stand without using my arms, hobbling increasing distances every day, and then – like an actual Jedi – one single stair. Each tiny new achievement felt like vaulting over a mountain. Here’s me at day seven, astonished to be standing up unsupervised:

That’s the face of someone grudgingly impressed by the tenacity of their meat cage.

Next time, I’m going to write about being discharged and adjusting to life on the outside.

Attention, women writers of the UK! Introducing Disturbing The Body, an exciting new ‘speculative autobiography’ project published by Boudicca Press. Submissions are open. We can’t wait to see what you come up with.

We’re looking for pieces that explore women’s personal experiences of fractured relationships with their bodies. Body themes could range from experiences with major operations, chronic health conditions or chronic pain, dealing with cancer, childbirth, disability, or any moment where a woman can feel powerless and out of the ordinary against her own body. Your piece must be about something you personally experienced, but you may be as creative as you please. Think the arch fantasy of Angela Carter, the anxious surrealism of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and the body horror of Margaret Atwood. Tell us about your body, your way.

I’m fairly new to comics and graphic novels. Since my surgery I’ve been reading almost as many comics as novels. Being forced to slow down has had its advantages – I’ve been getting through some brilliant graphic works. The latest is Celine Loup’s The Man Who Came Down The Attic Stairs.

Celine Loup is an award-winning cartoonist seen in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Penguin, and many more prestigious publications. Her work has been honored by The Ignatz Awards, Best American Comics, American Illustration, The Society of Illustrators, and CMYK. She is currently working on Hestia, a serialised erotic Gothic comic set in Ancient Greece.

The Man Who Came Down The Attic Stairs is as Gothic as they come. A loving couple expecting their first child move into a beautiful country house. When Emma’s husband goes to open the locked attic room, she hears a commotion and rushes to investigate. She finds her husband unscathed, but somehow… different.

It’s a Gothic interpretation of the anxiety surrounding motherhood written at a time in Loup’s life when she was ambivalent about starting a family herself and wanted to explore those difficult feelings in a safe place. That’s good horror, really, isn’t it? A sandbox for our worries.

I really enjoy Loup’s art style. It’s painterly, and bodies appear soft and natural. Wide sweeping vistas zoom in to uncomfortable close ‘shots’, raising the tension of isolation and paranoia. I love how Loup conveys loneliness through groups of almost empty panels lingering on repetitive household noises, on tasks that will never be complete. Always present is the baby’s scream, in wavering bold text – is she an exhausting burden, or is she trying to warn Emma of something?

There’s a lovely consciousness throughout of the absurdity of Gothic, that Castle Of Otranto camp that lovers of the genre embrace. The giant portrait of Freud behind the therapist’s head is very funny, but also perfectly illustrates the weight of outdated psychology hanging over women with postpartum depression and psychosis. There’s one particular moment of the uncanny that stands out – simple, elegant and absolutely chilling – but I won’t give anything away here.

Overall, this is a slice of well-executed psychological horror I’ll be returning to. Other reviews have made comparisons to Shirley Jackson, and they are spot on.

A belated happy Halloween to you all!

Ghost stories of the nineteenth century are enjoying a new lease of (un)life at the moment, with publishers scouring the archives for stories that have never since been republished or anthologised. Anyone who loves the genre knows the titles that regularly enjoy fresh publication, and, classic and beloved as they are, it can feel like they take up unnecessary space. There’s a rich untapped seam of ghostly tales, especially by women, and Black Shuck Books are working to rescue these stories from obscurity.

I actually received A Suggestion of Ghosts last Christmas and haven’t had a chance to get into it until now, but it’s spooky season and I felt the need to expand my knowledge of hitherto unknown authors.

First of all, what a fun cover. You know you’re in for a luxurious ride of delicious cliches. The collection is full of ancestral homes, hidden passageways, indomitable heroines with an eye for eligible bachelors, and a whole crew of spectres from the beyond. All the good stuff.

Of course, a good ghost story isn’t merely about a ghost, and there’s a range of interpretations of the form in A Suggestion of Ghosts. The collection shows what women authors of the latter half of the nineteenth century were doing with the ghost trope; fully indulging in the high Gothic or being more playful, working across genres.

The editor, J.A. Mains has typed out the stories by hand rather than relying on scanning software, so original spelling is preserved, which I appreciate. I love the biographical information on the neglected authors, too, some of whom published anonymously or only once. Others were prolific, like Katharine Tynan who published over a hundred novels and was championed by WB Yeats. There’s a real mix here. Tynan, with her knowledge of Irish witch lore, managed to elicit an “Oh, gross!” from me, which isn’t easy.

There are a couple of switcheroo type stories where the ghostly element is a device for a more straightforward romance. These were popular in ladies’ magazines, being less risqué than Gothic tales or sensation stories. In fact, they were generally aping them. The Ghost of the Nineteenth Century by Phoebe Pember is one of these, and I didn’t take to it, mainly because it’s full of nasty racist asides. The author was a Confederate nurse during the American Civil War. At the Witching Hour by Elizabeth Gibert Cunningham-Terry is a much better example of an author playing with genre and cutting edge technology in the same vein as Bram Stoker.

There are, predictably, more stories about or by the aristocracy than otherwise. That’s partly a genre thing (a sprawling ancestral home as your setting is basically the law) and partly a class thing (how many working class women of the late nineteenth century had the time, energy or encouragement to write?), but Lady Gwendolen Gascoyne-Cecil’s The Closed Cabinet is actually one of my favourites of the bunch. A young woman staying at her childhood friends’ home encounters rumours of a family curse, and though she laughs to be given ‘the haunted room’, the resulting nightmares lead her to make a terrible choice which might just change history.

But by far my favourite is A Speakin’ Ghost by Annie Trumbull Slosson. No stately homes here, and no dazzling heroines with a queue of suitors. Written entirely in patois, I thought it was going to be a slog to read, but the story unfolds into sensitive study on what ghosts mean to lonely people, to the unwanted, and how a ghostly encounter can mean radically different things to different people. This is why I love ghost stories. I want to see what they can do.

Overall, A Suggestion of Ghosts is an enjoyable collection showcasing a range of authors’ responses to supernatural encounters, ghost hysteria, and Gothic romance. There are authors who enjoyed success in their lifetimes, and those who only ever got one shot. This makes it an interesting and important snapshot of the period, and some of these tales will stay with me for a good while. Honestly, the more of these anthologies the better, and I’m happy to report Black Shuck Books have already published a sequel, which I’ll definitely seek out.