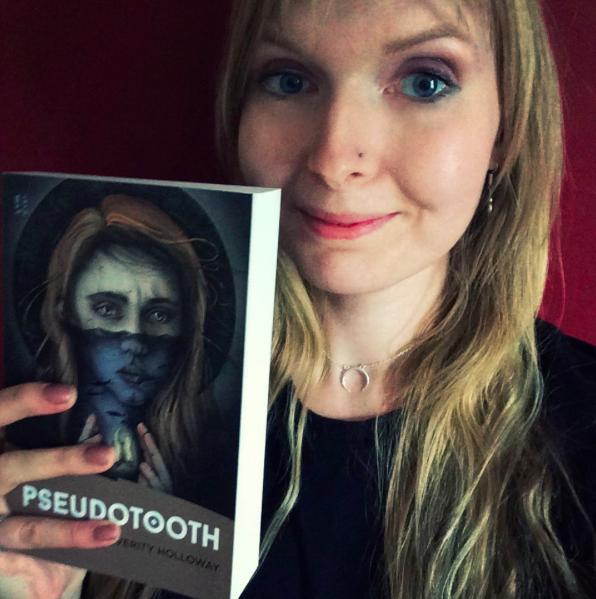

I’ve got a limited number of signed Pseudotooth bookmarks for all new Patreon supporters (including the $1 tier folks). As a patron, you’ll see patron-only poems, stories, and blogs while I embark on this new novel. Maybe even a few cute dog pictures, too.

I’ve got a limited number of signed Pseudotooth bookmarks for all new Patreon supporters (including the $1 tier folks). As a patron, you’ll see patron-only poems, stories, and blogs while I embark on this new novel. Maybe even a few cute dog pictures, too.

The Con Is On (again) – Nine Worlds and Not The Booker

I’ll be talking cityscapes in SFF with Amy Butt, Jared Shurin, and Al Robertson at Nine Worlds on Saturday. I’ll have a bundle of Pseudotooth bookmarks with me, so if you see me, say hi, and I’ll hand some out.

You find us from 11:45 – 12:45 in the Bordeaux Suite.

Panellists discuss the architecture of SFF – how cities are represented and how they can flavour a story. The discussion will range from the dystopian feel of cyberpunk urban jungle to the various flavours of fantasy as well as examining how real world cities are seen in fiction.

While I’ve got you, something cool has happened – Pseudotooth has been longlisted for The Guardian’s Not The Booker Prize! If you’re feeling benevolent, all you need to do to vote is go here and leave a comment in this format:

[yourusername] – Vote # 1 – [Book title only]

[yourusername] – Vote # 2 – [Book title only]

[A short review of one of the two books.]

You have until the 8th of August to vote. Remember to vote for two books on the list, or your vote won’t be counted.

Enter not into the path of the wicked – The Fatal Evidence of Professor Taylor

I’ve been talking to author Helen Barrell about her new book Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science out now from Pen & Sword.

Professor Taylor appears in your last book, Poison Panic, to deal with some murderous Essex wives. How did he capture your imagination sufficiently to make you devote a whole book to him?

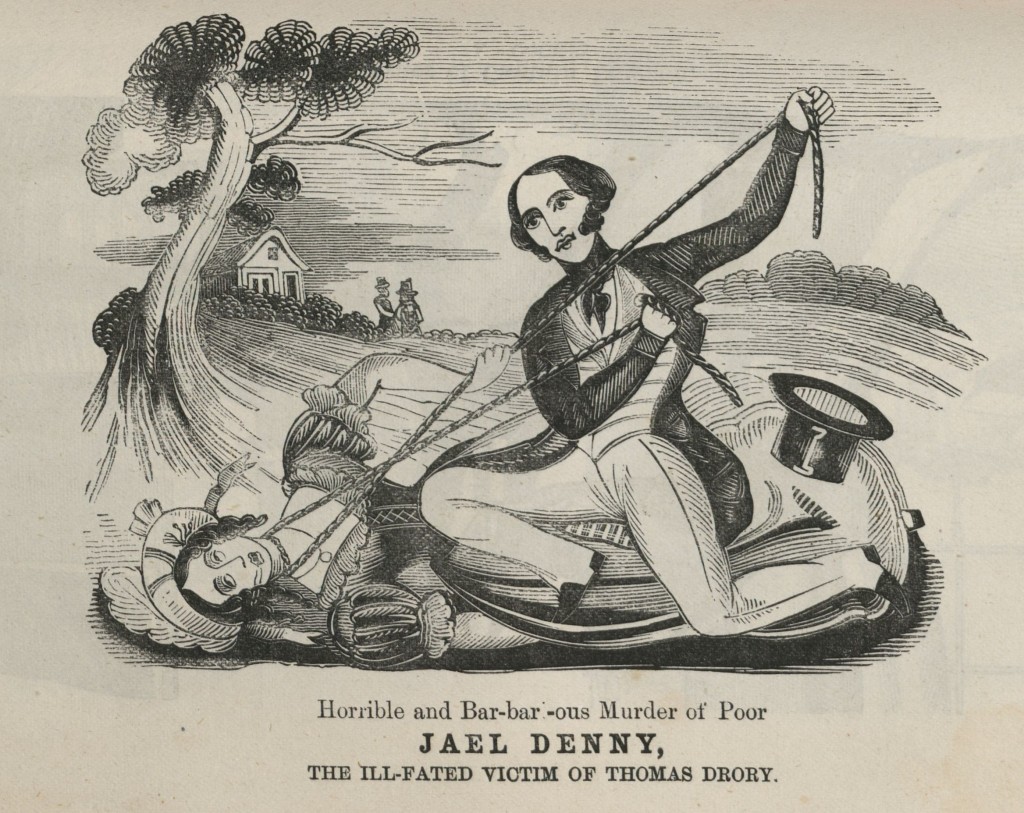

Taylor was the expert witness in the 1840s arsenic poisoning cases which involved Sarah Chesham, Mary May and Hannah Southgate. He was called in to work on all of the cases, and the papers were calling him “the eminent professor”, so I wondered – who on earth is this man? Then when I discovered he’d been summoned by the police to analyse bloodstains during the investigation of Thomas Drory, the Doddinghurst murderer,– and that’s as early as 1850 – I was surprised and intrigued.

I quickly found out that he’d been involved in a huge number of cases, and not always as a toxicologist, although that’s how he’s best remembered. Coupled with this was his massive output of books and journal articles, and his own editorship of the London Medical Gazette. His personality comes out in everything he writes; he’ll start in scholarly tone, but he just cannot resist injecting something of himself. It might be an unscholarly expression of amazement, it might be a sarcastic aside at an enemy, it might be a jibe at how stupid some criminals can be.

So not only are there fascinating cases involving a vast cast of Victorians, you’ve got a clever, sarcastic professor and the evolution of a science. Writing Taylor’s biography was utterly irresistible.

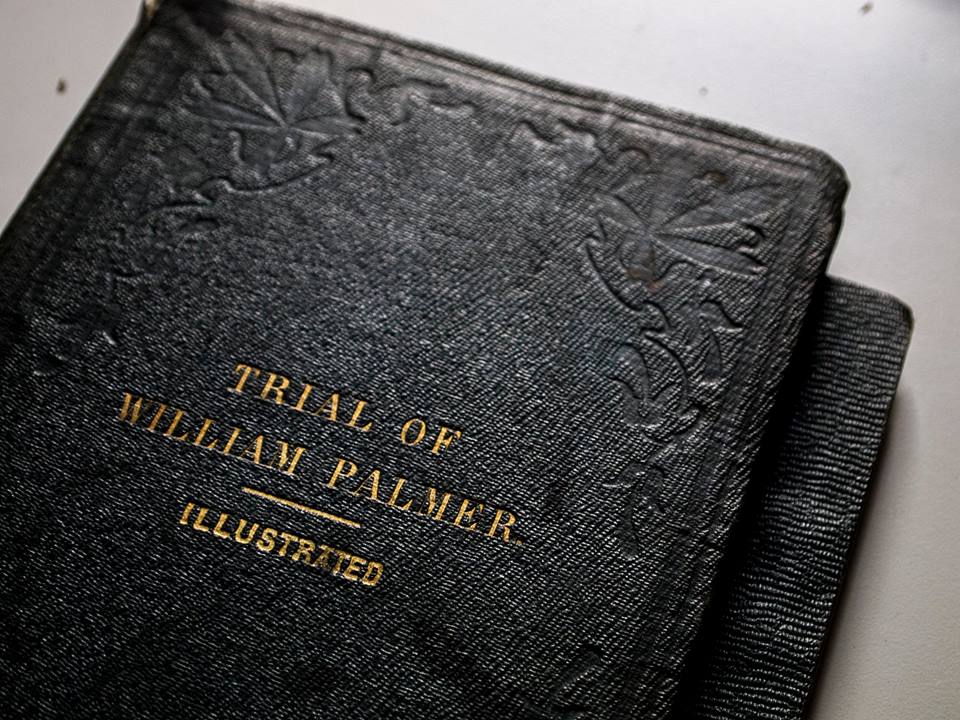

Victorian true crime enthusiasts will probably know Professor Taylor from the particularly nasty Rugeley Poisoner case. William Palmer, or ‘The Prince of Poisoners’, was a surgeon, and went to the gallows for his crimes. But that wasn’t the only time Taylor took down a fellow medical man for murder…

The Palmer and Smethurst trials are the only ones which Taylor worked on to be included in the famous red-bound volumes of the Notable British Trials Series. This is perhaps why Taylor is remembered almost exclusively for them, which means that nowadays his career is seen through a Palmer/Smethurst-tinged prism. But they were difficult cases, and Taylor himself harped on about them for years afterwards.

I have to say that researching and writing the 1856 Palmer cases gave me nightmares! I don’t live far from Rugeley, so my partner and I popped over on the train. We saw the pub where John Parsons Cook died, and I even went into the pet shop which occupies half of what was once Palmer’s house (I bought cat treats for my furry chums at home!). We saw the house where Palmer was born, and went to the church where Cook is buried and saw his grave. The stone was paid for by the priest who was the vicar at the time because so many people were visiting Rugeley purely thanks to the notorious Palmer, and along one side, almost buried now by grass and rising soil, is a line from Proverbs:

Enter not into the path of the wicked. Avoid it, pass not by it, turn from it, and pass away.

That night, I had a terrifying nightmare. I was in the churchyard at Rugeley in the twilight, and there was a horrible sense of evil in the air. I heard someone chant, over and over again, a line from the Lord’s Prayer: Deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil, deliver us from evil….

I managed to develop anaemia at the time, too, and so it felt like William Palmer was trying to finish me off as well! But it has to be said – when you’re writing about crime, real people died sometimes horrible deaths, by “unfair means”, as the Victorians used to phrase it. Although I found the Palmer chapter emotionally hard, I was relieved in a way because it meant that I hadn’t become desensitised.

But to move on to the other medical man who Taylor found himself toe-to-toe with, that would be Dr Thomas Smethurst.

These days, the jury is very much out on the 1859 Smethurst case, as some people think that Isabella, his “wife” whom he was accused of murdering, could have died from Crohn’s disease, or a similar intestinal complaint, aggravated by pregnancy. It was thought at the time that Smethurst used his medical knowledge to bump Isabella off.

Smethurst had originally married a woman who was 22-years his senior. While she was still living, he and Isabella Bankes, an heiress with an annuity, were carrying on with each other in the genteel lodging house where Smethurst was living with his first wife. Isabella was asked to leave by the landlady, and Smethurst quickly followed her. They were bigamously married, and not long afterwards, Isabella fell ill.

She had several doctors, besides her husband, caring for her, and all of them thought that something was off. One Sunday, Taylor was visited at home by a doctor bearing Isabella’s stool samples. Taylor lived in a on well-to-do Regent’s Park – one wonders what his neighbours made of the police and medical men who would drop by with articles for him to examine. On analysing one of the samples, Taylor found arsenic, and declared that Isabella was, quite likely, being poisoned, so her “husband” was arrested. Soon afterwards, she died.

Smethurst was a quack. He had a large collection of homeopathic remedies, and he had run a hydrotherapy spa in Surrey, which Dr Lane bought from him – in case that sounds familiar, Dr Lane was embroiled in the scandalous divorce case of Mrs Robinson. It’s very clear from his time as editor of the London Medical Gazette that Taylor had zero patience with quackery, and he had to examine all the homeopathy bottles looking for arsenic, and also antimony, which he found in Isabella’s body. Antimony wasn’t unusual in medicines, and arsenic was found in some as a pick-me-up – the risk was that Isabella could have been poisoned by one of the many remedies that Smethurst had in his possession. Or indeed, that so many bottles were an excellent way to hide the source of the arsenic, if Smethurst hadn’t already jettisoned it.

One of the bottles was mysterious to Taylor. It was almost empty and he only just managed to perform his favourite arsenic test – the Reinsch test – on it. It tested positive for arsenic, and he said that this was the likely source. Unfortunately, just before the trial, Taylor realised that he had made an error. The arsenic had in fact come from the copper which was part of the Reinsch test, and the mystery bottle had contained a chlorate which dissolves that metal. The arsenic in the copper gauze was released because the chlorate had dissolved it.

Taylor owned up to this error, and tried to turn it to his own ends as a scientific discovery. Well, every cloud has a silver lining, I suppose. The jury still found Smethurst guilty of murder, but he mounted an appeal. Newspapers groaned under the weight of people who had an opinion on the trial – it wasn’t only Taylor’s problem with the copper that some quarters of the public found fault with. Wilkie Collins lampoons this in his 1864 novel Armadale, concerning the trial of Lydia Gwilt, who was:

‘tried all over again, before an amateur court of justice, in the columns of the newspapers. All the people who had no personal experience whatever on the subject seized their pens, and rushed (by kind permission of the editor) into print. Doctors who had not attended the sick man, and who had not been present at the examination of the body, declared by dozens that he had died a natural death. Barristers without business, who had not heard the evidence, attacked the jury who had heard it, and judged the judge, who had sat on the bench before some of them were born.’

Smethurst’s sentence was overturned. However, he was tried for bigamy and sent to prison anyway.

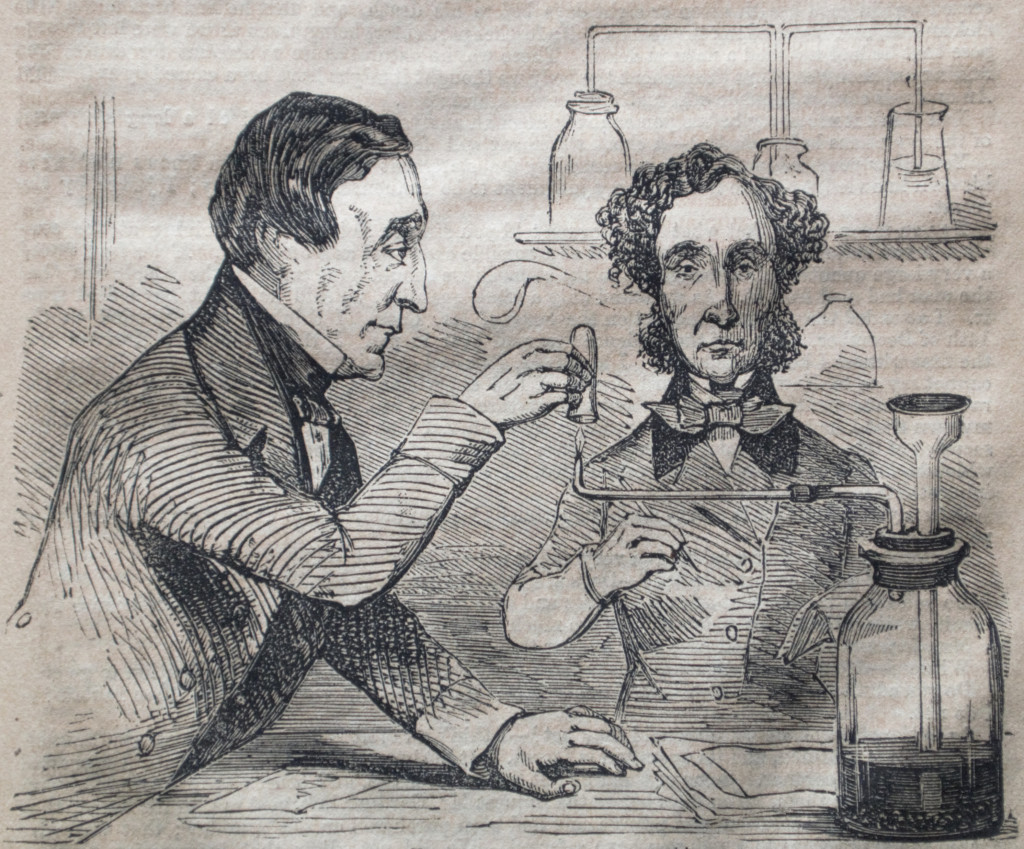

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

Alfred Swaine Taylor. Photograph by Ernest Edwards, 1868.

Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Professor Taylor had some fantastic interactions with the luminaries of the day. Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins were fans, but Sir Arthur Conan Doyle went so far as to base a character on him?

I was very excited when I found a list of all the books in Wilkie Collins’ library (I’m a librarian, so this thrill should not come as a surprise) and was pleased to see that Collins had owned not one, but two editions of Taylor’s On Poisons. It’s safe to say that whenever you see any poison turn up in a Collins’ novel, he’s probably drawn on Taylor’s extensive research and compiled cases to inform his writing.

Charles Dickens was such a fan that Taylor gets mentioned several times in his magazines, and at one point Dickens even visited Taylor’s laboratory at Guy’s Hospital and was given a tour. Imagine Dickens, who seems so cosy now, gazing in amazement at flakes of human liver in a jar, and a stomach in a fume chamber.

And it’s entirely possible that Taylor is one of several men whom Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was thinking of when he created Sherlock Holmes. It’s well-known that Conan Doyle admitted to basing Holmes on one of his tutors at Edinburgh Medical School, Dr Joseph Bell, and he also said that Poe’s detective Dupin was an influence.

However, if you read Dr Watson’s first meeting of Holmes in A Study in Scarlet and you know about men like Robert Christison (another Edinburgh Medical School Man, and a near-contemporary of Taylor’s) and Taylor, then it seems like Conan Doyle is deliberately referencing them in the character of Holmes. Watson’s friend tells him that Holmes has been ‘beating the subjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick’ which is a clear reference to experiments Christison carried out during the trial of Burke and Hare in 1828. He talks about Holmes experimenting on himself and friends with poison, and Christison had written about how he and his scientific chums had put arsenic on their tongues to discover if it had a flavour.

When Watson first sees Holmes, he’s just that moment discovered ‘an infallible test for blood stains’. The famous amateur detective puts a plaster on his finger, where he had pricked it to draw his own blood, saying, ‘I have to be careful, for I dabble with poisons a good deal.’ Blood stain and poison analysis? This sounds rather a lot like Taylor.

And there’s also Taylor’s height, which was often commented on. His energy, and his biting sarcasm to anyone who had the temerity to disagree with him, all seem rather Holmesian. Conan Doyle mentions the Palmer trial in The Adventure of the Speckled Band, and refers to one of Taylor’s books in The Stark Munro Letters; Conan Doyle’s semi-autobiographical novel about a freshly qualified doctor trying to find his feet. Although Holmes might not use his test-tubes very often, they are often a feature in the background, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if this is partly Taylor’s influence.

Taylor almost knew of Conan Doyle. In 1879, the year before Taylor’s death, ‘ACD’ wrote a letter to the British Medical Journal about some self-experimentation with a flower used for curing headaches. Taylor was providing editorial for the BMJ at the time, and so he’s very likely to have read Conan Doyle’s letter. What he made of it we cannot, of course, now know.

And he had a bit of a reputation for… well, losing his temper.

The article Taylor wrote after the Palmer trial is extraordinary piece of work; the toxicological equivalent of a schoolboy thumbing his nose and chanting “neener-neener”. It drips with sarcastic rage; he carefully collated other cases and provided a chart showing aspects of strychnine poisoning, but the footnotes are full of exclamation marks, barbed comments and even sarcastic schoolboy Latin.

He loathed Henry Letheby and William Herapath – expert witnesses hired by the defence at the Palmer trial – and to be honest, they loathed him in return. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the animosity began, although it could have started off as professional jealousy – they were working in a new field and were trying to convince the public of the import of their work. After the 1845 Tawell trial, when a woman had been murdered after drinking stout laced with cyanide, there were irate letters in The Lancet between Letheby and Taylor – Letheby was most annoyed that Taylor, who hadn’t been one of the expert witness at the trial, had conducted his own experiments (could you smell cyanide’s distinctive almond scent when mixed with alcohol?) and written about it in an article on cyanide poisoning. He was really very rude about Taylor; although he didn’t name names, he stated that some people were writing about cyanide ‘to gratify the cacoethes scribendi’ (insatiable desire to write), which is clearly a jibe aimed at Taylor.

The sniping that went on between Taylor and the men who ruffled his feathers is hilarious – it’s just like today when you see academics arguing on Twitter. If Taylor was alive now, that’s exactly what he’d do all the time, I’m sure of it!

He would fly into a fury over public health matters too – he appears to be the first scientist to go public with the surprising idea that arsenical wallpaper dyes might just be a bit dangerous. He was roundly disbelieved, and arsenical dyes continued to be used in the face of mounting evidence from scientists.

I remember you telling me about having to gently explain saponification to your editor. You even have a section called ‘A Horror of Bad Smells’! Without ruining everyone’s dinner, what’s the single grossest thing you’ve come across in Professor Taylor’s career?

This is such a hard question to answer –there’s a heck of a lot of gross things in Fatal Evidence (I did try to avoid too many details though, but it’s possibly not a book to read over lunch), and it’s impossible to mention them without turning people’s stomach. Sorry chaps!

So move along, unless you would like him analysing tapeworms that he found in the intestines of an arsenic poisoning victim. Or would you like the theory one doctor had, that Mrs Wooler was being poisoned with arsenic up her bottom via enema syringe? How about his examination of people who had been dead for some while, whose bodies had turned to soap such that the individual organs were unrecognisable, and yet he was still tasked with analysing them? One of these saponified corpses took him a week to examine and he wrote a letter to the Coroner who had hired him, to complain of the terrible headache the analysis had given him – and the letter, which did not hold back on gory details, was deemed worthy of reproduction in the newspapers!

I imagine you yell at the TV when a Victorian detective squints at a corpse and whispers “Arsenic!”.

Let’s just say I had problems with Taboo and the twenty-minute arsenic test in 1815. In 1850, with the far more efficient Reinsch test, Taylor took half an hour at a trial to analyse a bag of white powder. Now – would it be at all plausible that several years earlier, with a less efficient test, someone was able to examine human organs for arsenic – in twenty minutes? I think not.

This is your second book, and a natural progression from Poison Panic. As a writer, what have you learned about the process from that first experience?

In terms of purely practical things, sort yourself out with a nice place to sit. I wrote Poison Panic on an ancient laptop at the dining table, and ended up hurting my shoulder because I was hunched over. As I knew Fatal Evidence would be a longer book, and would require lots of research, I treated myself to a desk and a PC. And I wrote Fatal Evidence on Scrivener – it made life a lot easier.

There was such a lot of research required for Fatal Evidence, so I used a couple of spreadsheets to keep track of it all. I’ve got a massive timeline showing all of the cases I could find in the British Newspaper Archive which involved Taylor, and ones that I spotted from other sources such as his books and articles – I didn’t use all of them in Fatal Evidence, and I’m certain there’s still cases that are out there somewhere which I wasn’t able to find. I felt very organised, although I’ve still got a massive storage box next to my desk filled with box files of research! I’m loathe to chuck it all out, but I’m not sure where to put it.

I have to say that while I was writing Poison Panic, I was beset with fear that I’d never actually finish it. I was almost frozen sometimes by Imposter syndrome, thinking that I was rubbish and incapable, and that surely someone somewhere had made a mistake because I just couldn’t do it. But I kept going. So when I came to write Fatal Evidence, whenever that feeling tried to raise its horrible head again, I could face it down by going, “I’ve finished one book, I’ll finish this one too!” I wasn’t panicking as much, which made the process less painful – anaemia and nightmares excepted!

And I can’t really finish without saying you’ve upped your costuming game from last time. Nice tailoring.

Thank you! The irony is that my professor outfit is technically cross-dressing, seeing as I’m dashing about as a Victorian chap, but it’s much closer to what I wear on a day-to-day basis than the Victorian lady’s costume I had for Poison Panic last year! I wear a Walker Slater tweed waistcoat with trousers to work, and when the weather’s cooler, I’ll wear my tailcoat too. That said, I don’t wear a cravat or Mr Darcy shirt to work – perhaps I should.

Thank you, Helen!

Fatal Evidence is a worthy successor to Poison Panic, and a must for true crime fanatics. Don’t forget to follow Helen on Facebook for regular updates on her research.

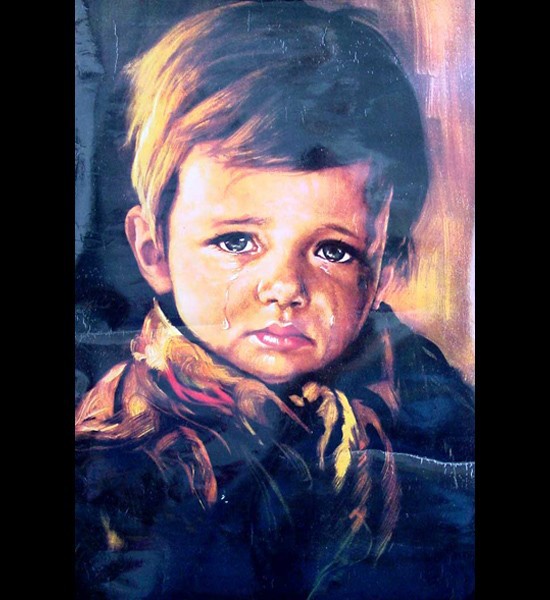

Tears For Fears – The Curse Of The Crying Boy

I have a recurring dream. I’m at my grandparents’ house, the one with the grotty pink shag carpet that enveloped my toes when I was small. I’m alone in the house, wandering through dark rooms with orange floral curtains and vases of papery Honesty, gathering dust. I touch the doorstopper that looks like a slab of chocolate but smells of burned things. The bath towels are scratchy with age.

In my dream, I never look up at the Crying Boy.

He disappeared from my life long before I was old enough to know his folklore, but even as a kid under ten, I could have told you that painting was cursed. The boy stands in a void, the ruffles of his infant blouse reminiscent of a Tudor prince awaiting the block. Something has made him cry. Not the tantrum of a little boy who’s just flushed his Lego down the toilet – there’s dread. We can’t see who or what he’s looking up at. And what is he pleading for? Comfort? Forgiveness? Mercy?

He disappeared from my life long before I was old enough to know his folklore, but even as a kid under ten, I could have told you that painting was cursed. The boy stands in a void, the ruffles of his infant blouse reminiscent of a Tudor prince awaiting the block. Something has made him cry. Not the tantrum of a little boy who’s just flushed his Lego down the toilet – there’s dread. We can’t see who or what he’s looking up at. And what is he pleading for? Comfort? Forgiveness? Mercy?

You’ll know The Crying Boy. Your own grandparents probably had one. Somehow, during the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, context-free devastated children struck a chord with the British public. There are dozens of versions of the Crying Boy, and by 1985, an estimated 50,000 prints of one Crying Boy variant had been sold in Britain.

It isn’t the first time the British have flocked to purchase pictures of children they aren’t related to. Where nowadays you might have a calendar of Yorkshire Terriers in your kitchen, Victorians exhibited their softer side by collecting sentimental pictures of children. This gauze of innocence still applied if you were a single man, and even if said children were unclothed (looking at you, Lewis Carroll). Sentimental infants go in and out of fashion – look at those unspeakable Anne Geddes bumblebee babies, for instance – but the Crying Boy has an altogether more intriguing history.

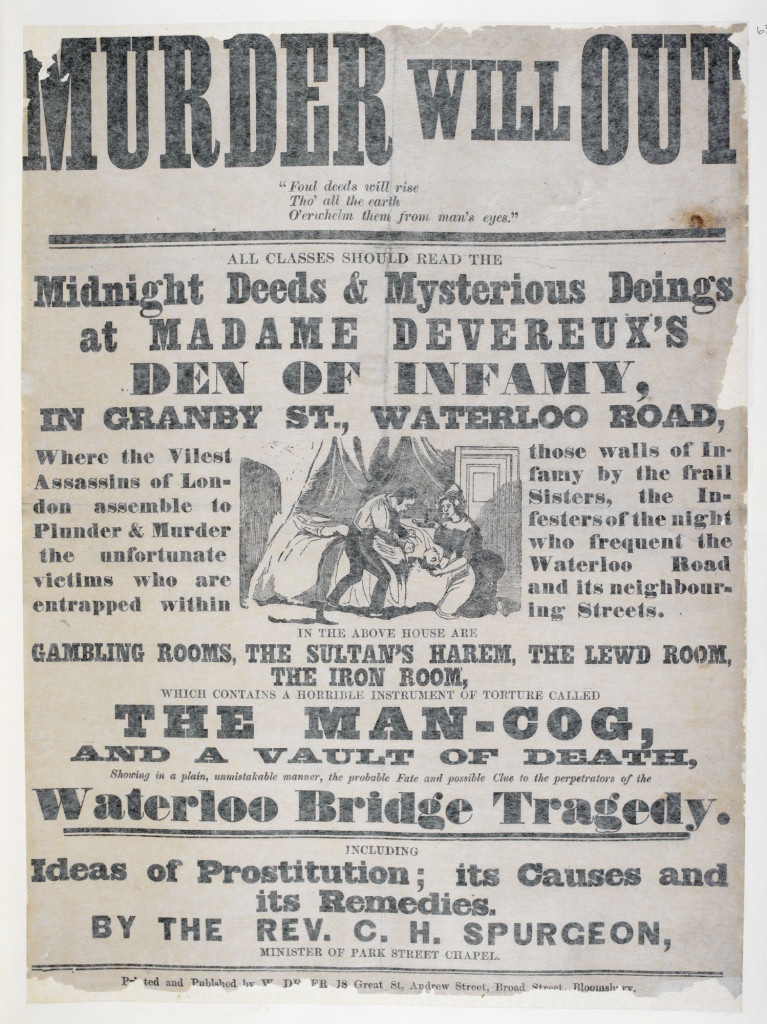

In September 1985, Ron and May Hall lost their home in that most retro of household disasters – the chip pan fire – leaving them with nothing but an intact Crying Boy. Days earlier, the couple had laughed at Ron’s fireman brother as he warned them of all the times he had attended blazes where the child had hung weeping on the walls. “Peter told us he wouldn’t have the picture in his house,” May told The Sun, “and nor would his friends at the fire station.” Maybe Peter and his friends just weren’t tacky as all hell. Or maybe they were onto something.

In September 1985, Ron and May Hall lost their home in that most retro of household disasters – the chip pan fire – leaving them with nothing but an intact Crying Boy. Days earlier, the couple had laughed at Ron’s fireman brother as he warned them of all the times he had attended blazes where the child had hung weeping on the walls. “Peter told us he wouldn’t have the picture in his house,” May told The Sun, “and nor would his friends at the fire station.” Maybe Peter and his friends just weren’t tacky as all hell. Or maybe they were onto something.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

Crying Boy disasters flowed steadily into The Sun’s mail room. Kevin and Julie of Rotherham lost their home to the flames. The couple were left with nothing but the clothes they were wearing and the infernal child on the wall. More than one reader claimed their children mysteriously died following the purchase of the painting. Someone swore they saw their Crying Boy move. One of the Sun’s pin-up girls – Sexy Sandra, 21 – played a trick on a friend by giving her Crying Boy spiky red hair, only to find the house wrecked by floods the following day. The boy, of course, was fine.

For those who don’t know, if it’s printed in The Sun, it might as well be printed on Beelzebub’s toilet paper. ‘Enough is enough, folks’, they wrote, as if the Crying Boy were some kind of foreigner, leftie, or feminist. ‘If you are worried about a crying boy picture hanging in your home, send it to us immediately. We will destroy the painting for you, and that should see the back of any curse there may be.’

Soon enough, The Sun had a pile of Crying Boys, and Sexy Sandra was armed with a can of kerosene to sort them out. The paper’s fine arts correspondent, Paul Hooper, was relieved to report that no muffled cries were heard as the paintings turned to ash.

The South Yorkshire Fire Service were forced to issue a statement assuring the public their Crying Boys would not turn on them, but their chip pans might. The Boy was a running joke in the fire service for years afterwards. Prints became the retirement gift du jour, but the picture retained an aura of bad luck long after the tabloids ran out of fuel. I recently saw the Boy donated to a charity shop, only to be immediately thrown in a skip by the management for being ‘too spooky’.

The South Yorkshire Fire Service were forced to issue a statement assuring the public their Crying Boys would not turn on them, but their chip pans might. The Boy was a running joke in the fire service for years afterwards. Prints became the retirement gift du jour, but the picture retained an aura of bad luck long after the tabloids ran out of fuel. I recently saw the Boy donated to a charity shop, only to be immediately thrown in a skip by the management for being ‘too spooky’.

The legend of Crying Boy lived on. Who was the model? Some say he was an Italian war orphan. Others said he was a runaway who disappeared after posing for his portrait; his anonymity played nicely into the cultural fascination with child murder victims. At school in the 1990s, we had The Boy Ghost who heralded your death if you caught a glimpse of him wandering the corridors. Children are inherently creepy. You can’t have innocence without acknowledging the threat of corruption and death.

The Crying Boy has entered urban legend, where he belongs. Thanks to the Internet, The Sun‘s campaign of burning can continue, despite a BBC documentary in which a leading expert in the field of cursed paintings explains that varnish can have fire retardant properties.

One of the final Crying Boy headlines read: ‘Tears for fears…the portrait that firemen claim is cursed.’ It’s an interesting choice of words. ‘Tears for fears’ relates to psychologist Arthur Janov’s Primal Scream therapy. Janov argued that neurosis is caused by the repressed pain of childhood trauma. This pain could be brought to conscious awareness and resolved through re-experiencing the incident, expressing the resulting pain during therapy. The patient trades their repressed fears for cathartic tears. In short, the inner child screams.

What does therapy have to do with a spooky newspaper hoax? The victims of the boy – or at least the real people who were captivated by the curse – were working class, struggling to make ends meet. Power cuts, unemployment and strikes made the post-war decades grim. Parents and grandparents harboured traumatic memories of recession and war. Perhaps this mass desire to bring innocence and sentimentality into the home was a method of banishing the ghosts of the early twentieth century, putting all those sorrows in a frame and leaving them safely on the living room wall. Maybe that’s why the legend of the Crying Boy still holds the attention – old trauma, like a curse, has a way of bursting out into our cosy homes.

So what happened to my grandparents’ Crying Boy, hanging behind the kitchen door? Their house never burned down. There were no floods. But there was one incident…

Whenever we ate Edam cheese, my mum would roll the red wax between her fingers and tell me the story of a juvenile food fight she had with her siblings in the old house of my dreams. Cheese rind is a natural projectile, and as the five of them pelted each other with Edam wax, a blob of it flew over its target’s head and hit the Crying Boy right on the nose. Choking with laughter, they peeled it off the canvas to discover it had stained the nose clown red. It was permanent, and my nan went spare. Every dinner time became an exercise in not sniggering at the picture, red nosed and tragic forever.

It was around that time that my youngest uncle decided he was going to grow up to be a karate master. He practiced high kicks at the kitchen door beside the Crying Boy, gradually training his muscles until he could connect with the top of the door in one kick. Only one day he got his shoe stuck. Losing his balance, his whole body ended up suspended from his ankle, which broke instantly, leaving him dangling there under the tearful gaze of the red-nosed boy.

For your listening pleasure (?), here’s yours truly reading from my novel Pseudotooth. I hope you like Chopin.

Read a free sample and get a copy at Unsung Stories.

And while I’ve got you, I was on Folklore Thursday this week talking about why you should never wander off with any strange pixies. It’s all fun and games until… well, ask Richard Dadd…

The con is on

Good morning, sweaty British people. Do you fancy spending tomorrow in a nice air-conditioned aircraft hanger with thousands of people dressed as Pyramid Head?

You do? Splendid. See you at ComicCon tomorrow! Here’s where you’ll find me…

Dream a little Dream – The Importance of Dream Worlds in genre fiction:

Dream logic and Dream Worlds have been a staple of genre fiction for years now, but they can be a very tricky thing to pull off right. Join authors Oliver Langmead (METRONOME) Verity Holloway (PSEUDOTOOTH) Claire North (THE END OF THE DAY) and Catriona Ward (RAWBLOOD) as they discuss the use of dreams in fiction.

Exact time: 10:00am – 11:15am

Day: Sunday 28th of May

Lower Platinum Suite – Author signings afterwards – Books available at Forbidden Planet Int.

Unsung Stories Presents: A Very British Scene

For a tiny island on a very large planet, the British turn out a lot of stories. Why is this, and how do they differ from the wider market? Join Unsung Stories authors Aliya Whiteley (THE ARRIVAL OF MISSIVES) Verity Holloway (PSEUDOTOOTH) and Oliver Langmead (METRONOME) as they discuss the role that Great Britain has played in influencing and expanding the staples found within speculative fiction.

Exact time: 12:30pm – 1:45pm

Day: Sunday 28th of May

Lower Platinum Suite – Author signing immediately afterwards – Books available from Forbidden Planet Int.

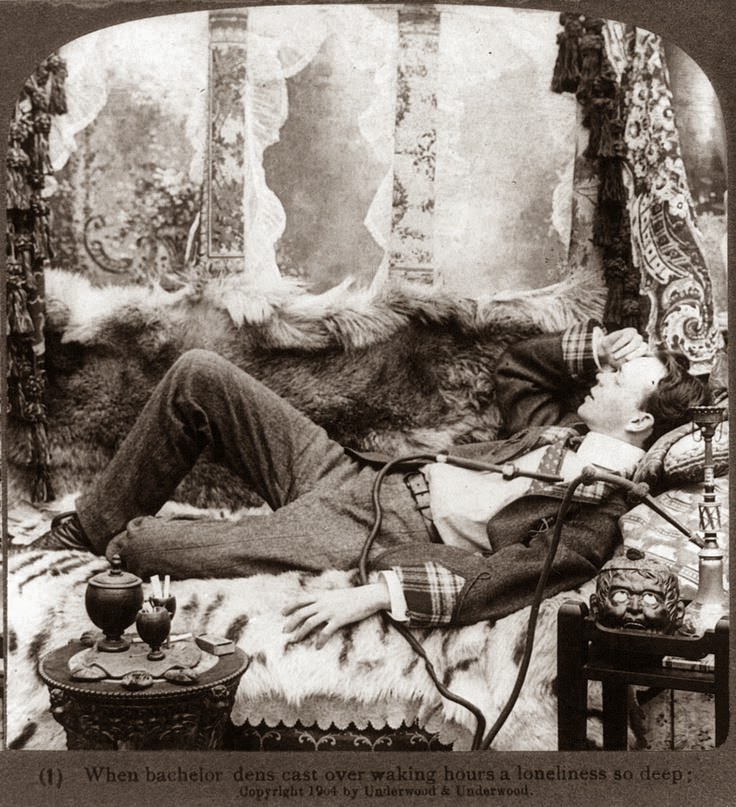

New story: A Little Star

Phew. Fresh off the train from Unsung Live #8. Met some lovely people, listened to some lovely (and scary and violent and hilarious) fiction, and got to share A Little Star, my story of an opium den, a convict, and a shiny little something. It’s online now, if you fancy reading it.

A lamp with a shade of red paper. No matter what draughty lodge or bawdy house Benjamin laid his head for the night, he saw that Lime Street crimson whenever he closed his eyes, the way another man might see the face of a girl he loved, or a child a ghost in the doorway.

Pre-Raphs in Space

I’m surfacing for a brief moment as I haven’t blogged properly for yonks, and with Pseudotooth coming out next month I need to make it look like I’m alive.

Those who know me are well aware of my weakness for Beautiful Tragic Dead Boys. This means I frequently get gifts of antique photographs to hang on my wall where I can imagine the anonymous subjects were thwarted poets who died at sea. We all have our preferences.

Rejoice: I have a new Beautiful Tragic Dead Boy. Nils Asther was beamed down to earth in 1897 by the same aliens who gave us David Bowie. He grabbed my attention a few weeks ago for being the dead spit of my Az from Beauty Secrets of The Martyrs. I had in mind an androgynous silent film star look for Az, and Nils’ dark, unearthly prettiness, though rather too tall, is precisely how Az materialised in my head, stealing my silverware and hijacking the neighbours’ wifi.

Thank you, Outer Space, for loaning us your bisexual cheekbony creatures.

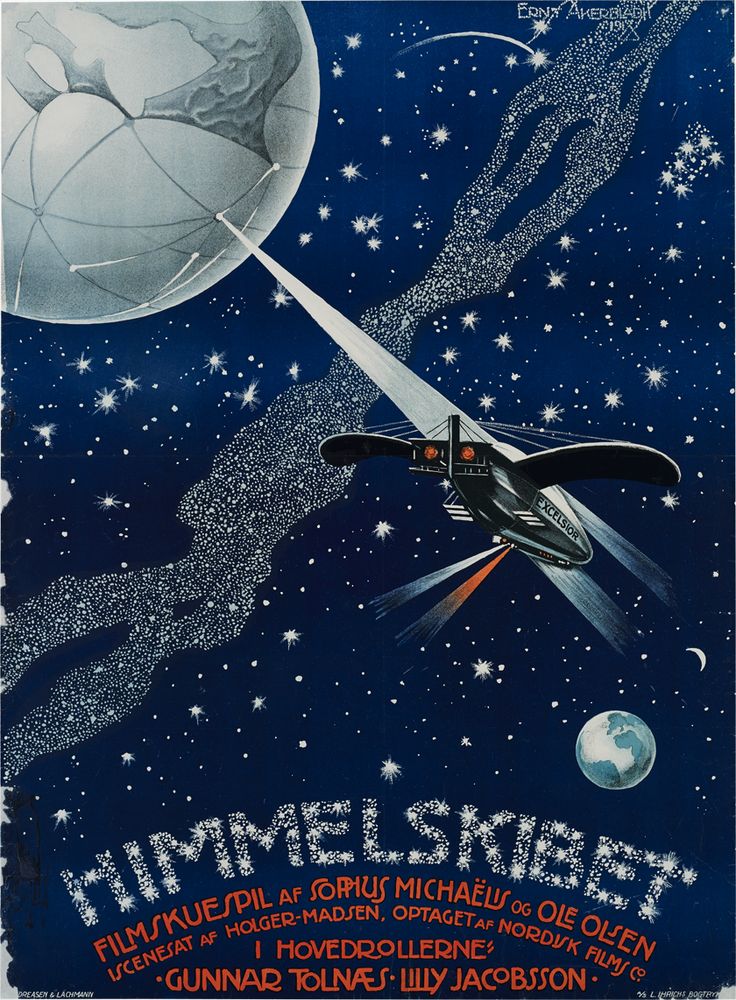

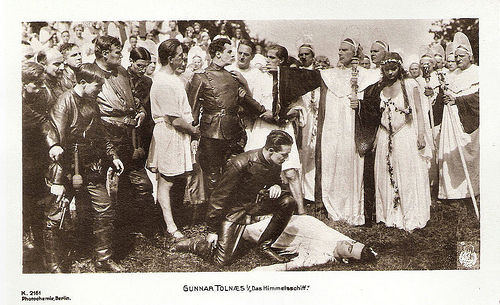

So I’ve been watching as many Asther films as I can find. Mostly, he was the romantic bad boy, which he hated, but there are a few surprising films. Himmelskibet (A Trip To Mars) featuring a twenty-one-year-old, rather skinny Nils as a citizen of Mars, which is probably where he came from in the first place. While lacking the whimsy of Georges Méliès’ 1902 A Trip To The Moon, A Trip To Mars – made in 1918 – has a certain Pre-Raphaelite flavour that caught my eye.

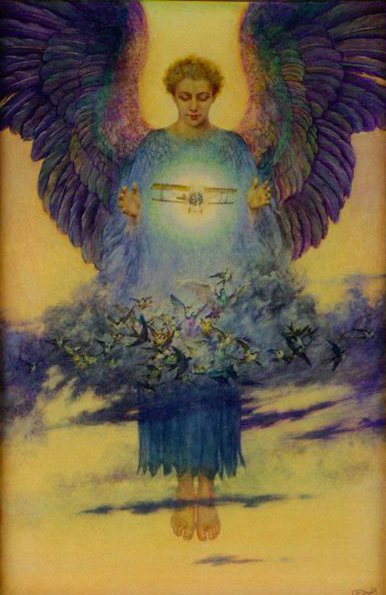

As unlikely as it may seem, the Pre-Raphaelite link to sci-fi is something that keeps popping up. (See the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood post on Princess Leia for some hair-talk.) Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were, by definition, interested in the naturalistic style of art before Raphael, they still interacted with the issues of their own Victorian age through a lens of medievalism and myth. Science, okay, not so much – Rossetti, famously, had no idea if the sun revolved around the Earth or vice versa, and argued it was unimportant anyway – but later disciples of the PRB did dip their toes into the world of modern technology. This 1910 Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale painting of an angel guarding a biplane has always fascinated me…

There’s something odd about watching a film about space exploration made during the First World War. And there’s a yearning quality to A Trip To Mars. While the Earth is tearing itself apart, Mars turns out to be populated by peace-loving vegetarians. We get to watch a rocket full of uniformed Earthmen barging onto the peaceful planet where everyone floats around like Grecian deities. It’s as if Man has found Eden again, and another way to ruin it all.

Are the Earthmen ready for the Martians’ message of peace and love, or will they give in to the temptation to hurl grenades for no good reason? Here’s their chance to go back in time and halt things before they go wrong – something the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were deeply concerned with.

Here are a few of my favourite rather Pre-Raphaelite moments. You can watch the whole film here.

And finally, a spaceship decked in flowers. Just because.

New Story: Trenchfoot Theatre

I adjust my bonnet, take a breath, and emerge into the lamplight. I can see the public in the cheap seats, and they thunder their appreciation with hands and feet and fag smoke. I smell spilt beer and ladies’ perfume disguising sweat, and I fear I will be sick. My debut. Climbing up and out and over the smoky precipice, I want to turn tail and run for the wings, but I wouldn’t survive it. The master of ceremonies wields his gavel like a sabre.

“Ladies and gennlemun, boys and girls! MISTER – PADDY – SYKES!”

Surviving The Season Whilst Spooky

This is me doing my annual Goth National Service. Here’s my list of dark little treats and recommendations to help you traverse the purgatory of December.

How To Survive The Most Wonderful Time of The Year When You Find This Time of The Year Pretty Unbearable Actually.

2016 has been nightmare upon nightmare, but it was last year that we lost the incomparable Christopher Lee. Mr Lee’s baritone M.R. James readings have become a Christmas tradition in my household, and thank all the sunken crowns of East Anglia, you can buy a DVD of the lot. Forget carols at Kings’. Don your mortar board and enter James’ study for an evening of room-temperature madeira and dread.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bc095E5DwEE

For reading matter, cosy won’t cut it. You want something cold. Lauren Owen’s The Quick is a fresh look at the vampire myth, and it stayed with me for its sense of the physicality of being undead as much as Owen’s clever wordplay when it came to the child blood-drinkers of Victorian London.

In The Malleus Maleficarum, Kramer and Sprenger wrote that Christmas was a good time for witches to work their magic, as all the revelry made bad Christians easy to bring over to the Devil. In that spirit, please enjoy Jeanette Winterson’s The Daylight Gate.

Incense Avignon by Comme des Garçons is bottled ritual. Morrissey used to have it sprayed into concert halls before he came onstage to foster a feeling of holiness and dread. I always think it smells like Rasputin might if someone forced him to have a bath. Holy smoke and hard drink.

Incense Avignon by Comme des Garçons is bottled ritual. Morrissey used to have it sprayed into concert halls before he came onstage to foster a feeling of holiness and dread. I always think it smells like Rasputin might if someone forced him to have a bath. Holy smoke and hard drink.

And for your filthy sinful face…

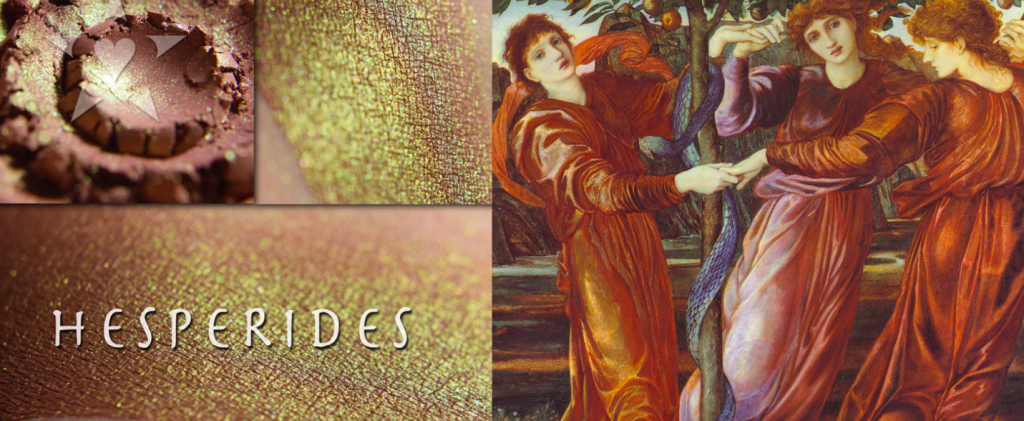

I’ve been a fan of Aromaleigh cosmetics for years and years, and they keep getting better. I never end up in the MAC shop, because Aromaleigh not only beat them on pigment, price, and quality, but their ranges are inspired by arse-kicking historical women, Dante’s Inferno, and deep space, which are really the only topics worth focusing on when browsing eyeshadows. The Hannibal-themed collection, This Is My Design, is particularly delightful for having a copper duochrome shade called Abattoir. “Ooh, you’re so glittery. What is that?” “ABATTOIR.”

I’ve been a fan of Aromaleigh cosmetics for years and years, and they keep getting better. I never end up in the MAC shop, because Aromaleigh not only beat them on pigment, price, and quality, but their ranges are inspired by arse-kicking historical women, Dante’s Inferno, and deep space, which are really the only topics worth focusing on when browsing eyeshadows. The Hannibal-themed collection, This Is My Design, is particularly delightful for having a copper duochrome shade called Abattoir. “Ooh, you’re so glittery. What is that?” “ABATTOIR.”

I’m going to close this year’s guide on an unusually festive note with Mediaeval Baebes, because if there’s one thing December is good for, it’s putting a big blanket around your shoulders, drinking red wine and pretending to be a weatherbeaten medieval king. Mediaeval Baebes are especially good at taking traditional carols and imbuing them with that sense of midwinter darkness you just don’t get with Slade. Salva nos, stella maris…

And remember, at Christmas, Christopher Lee always wore Vincent Price’s special Christmas fez. Make spookiness a part of your festive traditions, for the sake of our dear departed Goth Granddads.