They say that one passion leads to another. Long before I discovered Dante Gabriel Rossetti, I lived in Gormenghast.

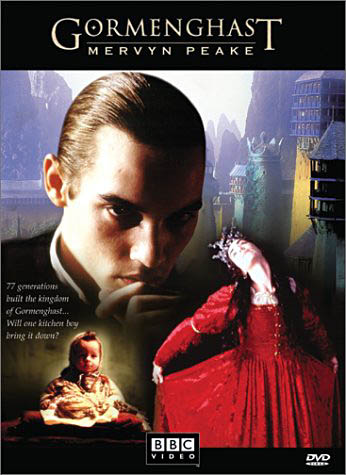

Between school bullies, kidney infections, and the oncoming Iraq war (which, I’d somehow convinced myself, was my fault), the year 2000 was a dismal time to be fourteen. But when the BBC released a four-part adaptation of Gormenghast in time for the Millennium, something shifted. From my hospital bed, I imagined the mauve peaks and crumbling spires of the castle on the horizon. I stopped doing my homework. Mervyn Peake’s Machiavellian fantasy was a safe place to escape to.

I never grew out of it. At my first University graduation, seeing the professors traipsing down the aisles in their gowns and mortar boards, I whispered excitedly to the boy next to me: “This is just like Gormenghast!” He had no idea what I was on about.

Years pass. We grow up, our tastes evolve. I fell out with high fantasy, fell into the nineteenth century. But, over a decade after my first encounter with Gormenghast, thumbing through my paperback trilogy, something sounded familiar…

“A girl of about fifteen with long, rather wild black hair. She was gauche in movement and, in a sense, ugly of face, but with how small a twist might she not suddenly have become beautiful. Her sullen mouth was full and rich – her eyes smouldered. A yellow scarf hung loosely around her neck. Her shapeless dress was a flaming red. For all the straightness of her back she walked with a slouch.”

Oh, hello, Jane Morris.

For a fourteen-year-old reader, Lady Fuchsia Groan is an easy character to relate and aspire to. Living in isolation where ‘the halls, towers, the rooms of Gormenghast were of another planet’, her response to most things is to run away to her dark attic of storybooks and paintings. She is a petulant child playing Ophelia and Juliet, dying to fall headlong into a world of chivalric romance and adventure.

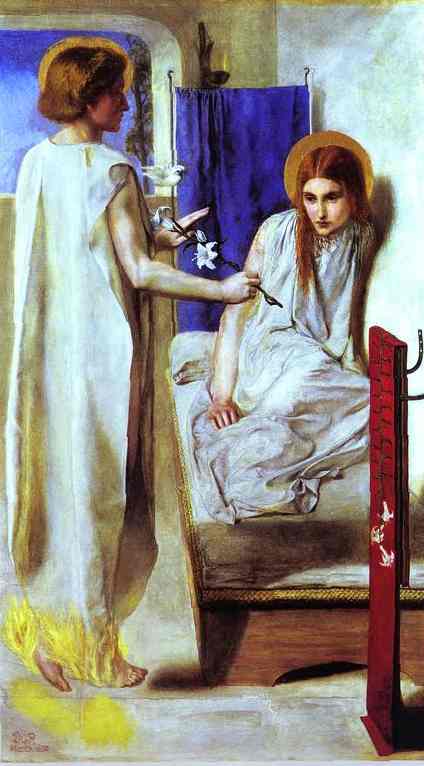

Fuchsia – in Peake’s own illustrations and his text – has unmistakable similarities to Rossetti’s Jane. Like La Pia, Fuchsia glowers with the lethargic energy of someone who wants to be somewhere else but isn’t sure where. Her unkempt hair and pronounced features give her the ‘unpretty’ Pre-Raphaelite beauty the Victorians were so bothered by. Jane was considered unfortunately unattractive by many. Fuchsia, too.

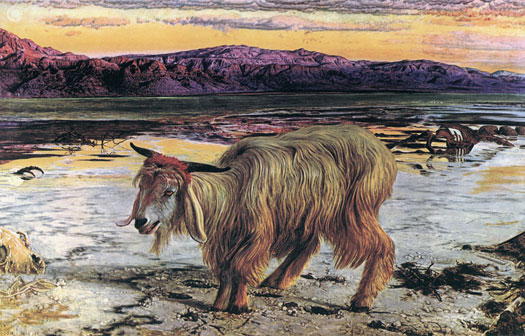

There are Pre-Raphaelite echoes in every corner of Gormenghast. Maybe it’s the meeting of the Gothic and the Chivalric, the tragic and the absurd, or Peake’s own network of literary sources including Lewis Carol and The Brothers Grimm. Peake’s childhood in China and later studies at the Royal Academy gave his work a sense of ancientness and the exotic that reminds me of Holman Hunt’s picking and choosing of historical and cultural details. You can see it in The Hall of The Bright Carvings and the almost Tibetan descriptions of the endless corridors and slanting roofs of the castle.

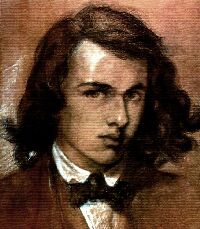

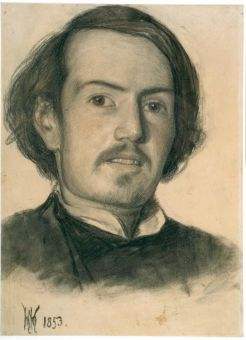

Mervyn, acting casual

As a war artist in the 1940s, Peake saw terrible scenes of human cruelty in the rubble of the bombsites and the concentration camps. Perhaps it was only natural to head for the dusty safety of the past.

The BBC adaptation – which I realise is not to every Peake-purist’s taste – is funhouse mirror Pre-Raphaelitism. Nature is vast and unfathomable. Steerpike wheedles his way into Fuchsia’s favour by claiming to be “like the knights of old, your ladyship” only to find he can’t possibly live up to Fuchsia’s fantasies. In John Constable’s later stage show, Fuchsia is even given red hair. (Actual audience comment: “This is horrible. They said it was fantasy. It’s nothing like Harry Potter at all.”)

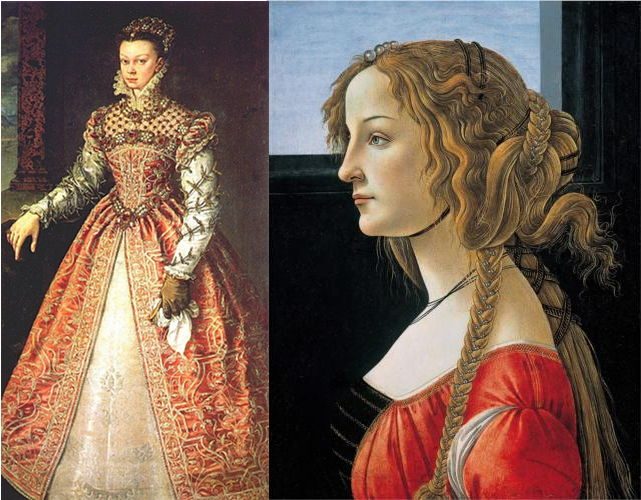

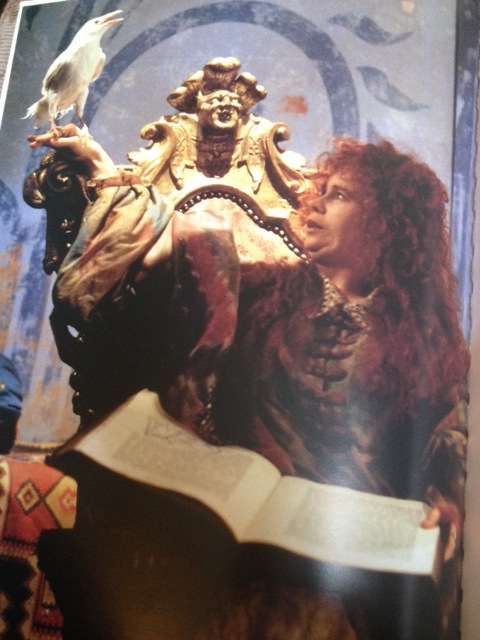

The BBC costumes are luxuriant. Fuchsia starts off as a teenager in a loose red velvet dress embroidered with stars. As she gets older and sadder, her outfits become heavier, more stiffly structured, until she is dragged down into the foaming floodwaters like Ophelia, leaving flowers in her wake.

The costume department referred to some of the same sources the Pre-Raphaelites did – Velázquez and Botticelli – resulting in voluminous layers of fabric and detail (even hazelnuts as buttons!) like a mad dressing-up session in a museum vault. Actress Neve McIntosh would gain two inches in height after taking off Fuchsia’s weighty gowns. Rossetti, with his reams of fabric cluttering up the house, would have loved it.

Excuse the poor quality photograph, but wouldn’t Rossetti have made a great job of this still from the film as a painting? Minus the prosthetic chin.

I wonder if I would have reacted so strongly to the Pre-Raphaelites had I not experienced Gormenghast so young. One good thing leads on to another. What’s next?

Buy The Gormenghast Trilogy, the BBC miniseries on DVD

, or the fantastic soundtrack

by Sir John Tavener who, coincidentally, has Marfans.

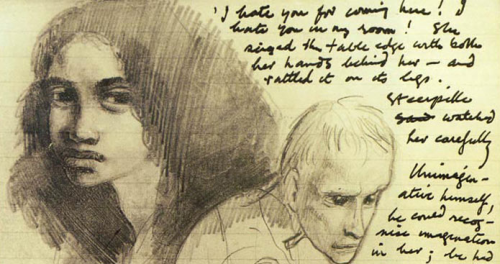

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”.

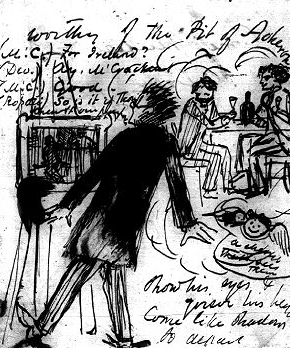

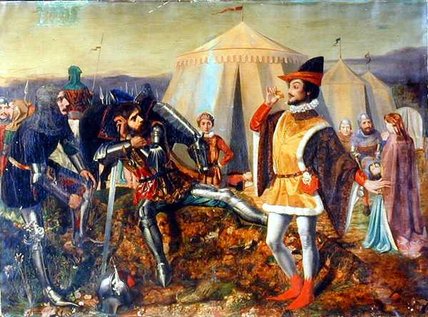

By all accounts, Walter was a nice young thing, and highly sought-after as a model among the PRB. He was especially close to Rossetti, cackling over clueless patrons in the rooms they rented together in Red Lion Square – purportedly so dingy that Walter’s doctor was moved to pat Rossetti on the head and mutter “poor boys, poor boys”. Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.

Hamlet himself, in spite of his being perched upon a square box in the gawky, shrinking attitude of a delinquent school-boy, might, with an effort, be allowed to pass as not wholly un-Shakespearian; but his yellow, pink, and blue majesty Claudius, who pokes towards his nephew in a withering attitude – copied, perchance, from the Bayeux Tapestry – is.

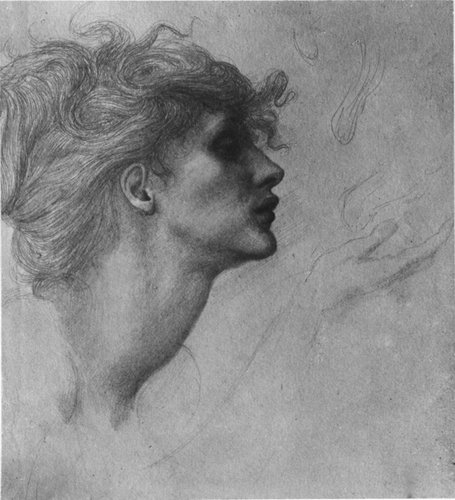

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy.

What I love about Burne-Jones’ nudes, especially the females, is their long, cold, anatomical beauty. There’s a sickliness about them I enjoy. Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence.

Woman In An Interior features Rossetti’s cockney darling, Fanny Cornforth, looking hard as nails. She wasn’t invited to stay at Kelmscott with him, strangely enough. I like her masculinity, here. Many men in Rossetti’s circle were mildly afraid of her, despite her being, by most accounts, a cheerful presence. The certain secret thing he had to tell

The certain secret thing he had to tell