Lately, I’ve been reading Peter Ackroyd’s The English Ghost: Spectres Through Time

Lately, I’ve been reading Peter Ackroyd’s The English Ghost: Spectres Through Time , a compendium of hauntings scattered across English history. I love Peter Ackroyd. He is my favourite walrus-shaped historian. I once had a dream in which we were best friends and he’d allow me to lounge around on scatter cushions in his flat at the top of an old London warehouse, reading his tomes while he organised his cravats*.

, a compendium of hauntings scattered across English history. I love Peter Ackroyd. He is my favourite walrus-shaped historian. I once had a dream in which we were best friends and he’d allow me to lounge around on scatter cushions in his flat at the top of an old London warehouse, reading his tomes while he organised his cravats*.

Being a series of short witness-accounts of strange occurrences, there are a lot of ghosts to take in. Just when I’ve decided on a favourite, Peter Ackroyd presents me with something twice as horrible oozing out of a seventeenth century cupboard and I have to revise my leader-board accordingly. There’s the bodiless entity creeping around Ely, punching people in the side of the head. Then the man in the dripping raincoat, who seems to love being run over on the A38 again and again. And I couldn’t leave out Borley Rectory, the supernatural fire-safety story. Whether you believe in them or not, the history of England is riddled with boggarts, bugs, wraiths, shucks and clabbernappers.

So here’s my contribution.

I was nineteen and living alone in a flat in one of the three-storey Victorian houses on Cambridge’s Chesterton Road. The ceilings were high, the heating was sluggish, and the basement flat – for some unknown and therefore definitely sinister reason – was only ever rented to men. The men had two entrances separate to the main building where the women lived. One was at the front, down a set of steps behind some iron railings, and the other was down another set of steps in the paved yard out the back. It was here that I met my ghost.

It was an old house but it wasn’t a creepy one. I had a room on the ground floor, with a miniature kitchen, a computer desk in the old fireplace nook and a small wall-mounted bookcase with closed sides, packed tightly with books. I never saw the other residents, even in passing, (I kept student hours), but I liked it that way. Only one or two odd occurrences made me pause. The first involved the bookcase.

Quite often, when I came in from my classes at Anglia Ruskin, my books would be on the floor. The one I usually found six feet from my little bookcase was Literary Theory: An Anthology , 1336 pages long, weighing as much as a carrier bag full of sand. If it had slipped off the shelf, it wouldn’t have bounced cheerfully across the carpet for such a distance. But it did, repeatedly, and only while I was out.

, 1336 pages long, weighing as much as a carrier bag full of sand. If it had slipped off the shelf, it wouldn’t have bounced cheerfully across the carpet for such a distance. But it did, repeatedly, and only while I was out.

This didn’t worry me. My half-serious theory was that some disembodied visitor objected to the cover art – a Victorian surgeon contemplating an inappropriately alluring female corpse – so I’d apologise out loud and place the book back on the shelf. The ‘rearrangements’ kept happening, but they weren’t distressing. I wasn’t expecting a one-to-one audience with a full-body apparition.

As it happened, the afternoon I saw her, I wasn’t alone. My dad had come over from Ipswich to visit, and we were out in the yard. He was subjecting my bike to a bit of no-nonsense-Navy-engineer maintenance. He wanted me to cycle back and forth from classes, but I’m a ditherer, and cycling in a city seems like just another way for me to end up in hospital. My bike had lain dormant for months under a plastic sheet, and dad was grappling with it in the small bike shelter as I loitered a few feet away by the steps leading down to the men’s basement flats.

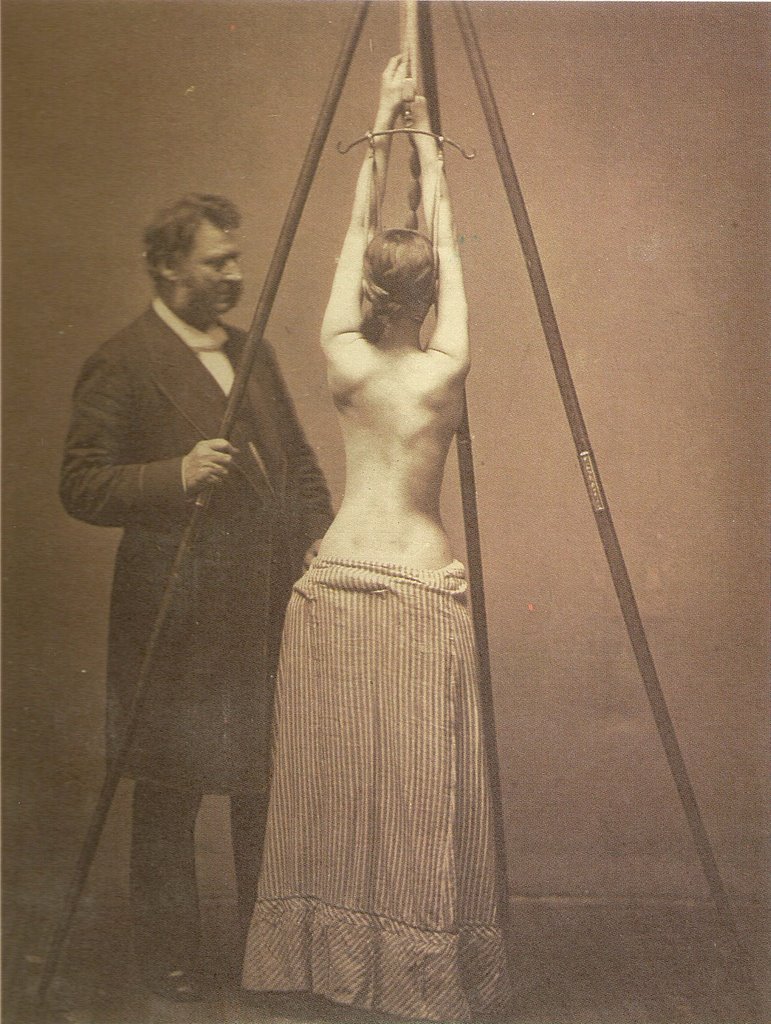

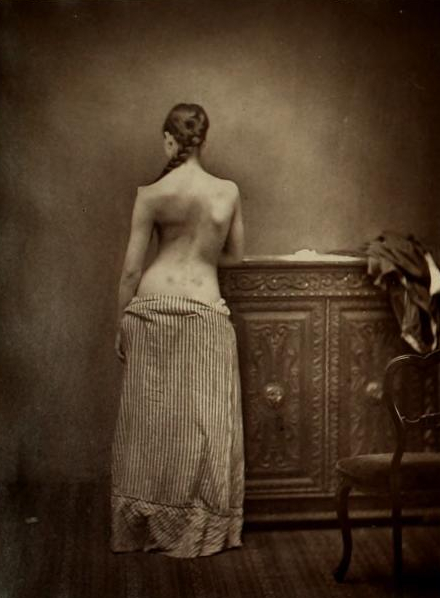

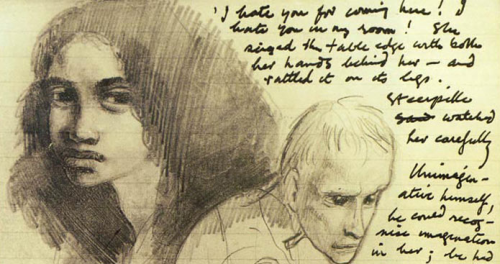

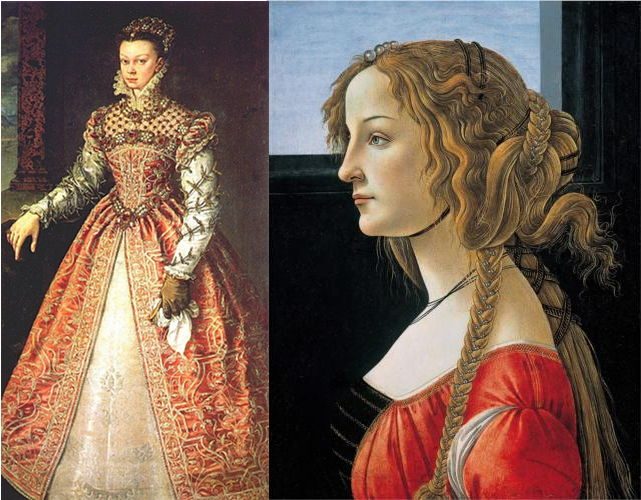

I don’t know what made me turn around. But when I did, I was facing a young woman holding a tray. Her muscles were in the process of dropping the tray – a kind of frozen flinch – because I’d startled her. Which, I suppose, was natural, as she was a maid in a long blue dress and apron and I was a six-foot vision of the future in drainpipe jeans and smeared eyeliner. She was solid, around five-feet-seven, dark-haired, and her uniform was similar to this unnamed girl’s on the right.

I don’t know what made me turn around. But when I did, I was facing a young woman holding a tray. Her muscles were in the process of dropping the tray – a kind of frozen flinch – because I’d startled her. Which, I suppose, was natural, as she was a maid in a long blue dress and apron and I was a six-foot vision of the future in drainpipe jeans and smeared eyeliner. She was solid, around five-feet-seven, dark-haired, and her uniform was similar to this unnamed girl’s on the right.

I registered all this within the space of two seconds. There wasn’t time to speak. She was gone. She didn’t disintegrate, or fade, or even just wink out. I can only say that she simply wasn’t there any more.

Rather than the ice-crystals-in-the-blood shock so many people in Peter Ackroyd’s book reported after meeting with ghosts, I felt guilty. I wasn’t frightened, but she most definitely was. I think she must have dropped her tray, whenever the connection faltered and she found herself alone. I turned back to dad, who was still engrossed in my flat tires, and never mentioned the girl to him.

In The English Ghost, Peter Ackroyd describes the categories of hauntings: the conscious souls of the dead, the replaying of actions, nature spirits, omens good or bad… but I believe my ghost wasn’t a ghost at all. I think there was a glitch in time; a window allowing us to see each other. Perhaps the moving books were a symptom of whatever quantum hiccup was focused on the house. It’s fun to speculate, and I especially like the possibility that maybe, just over 100 years ago, a parlour maid rushed back into the scullery after breaking a trayful of china, and told her friends about me – the girl in the yard.

* There’s still time, Peter, if you’re reading this.