Is there anything better than perusing glossy photographs of artificial limbs and trepanned skulls over one’s breakfast? I think you’ll find there isn’t.

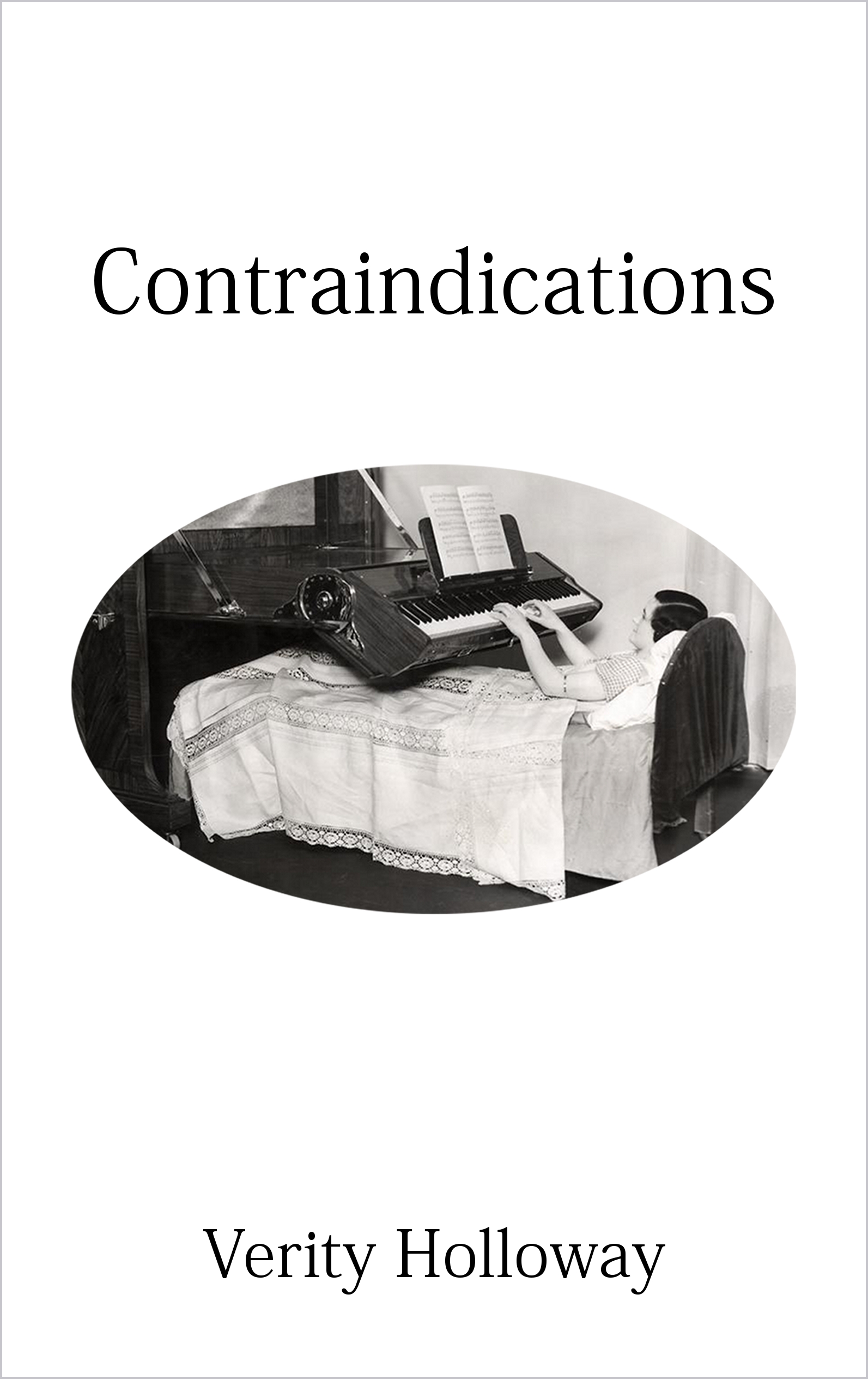

This week, I won a copy of the Wellcome Collection’s brand new ‘Guide For The Incurably Curious’.

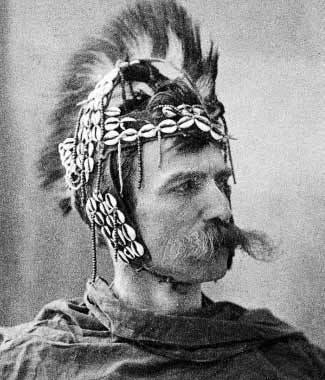

Wellcome is my favourite museum. If you have the slightest interest in wunderkammer, it’s a playground. The perfect balance of the medical, the historical, the scientific and the artistic, lovingly founded by Victorian philanthropist Henry Wellcome. Look upon his facial hair and tremble.

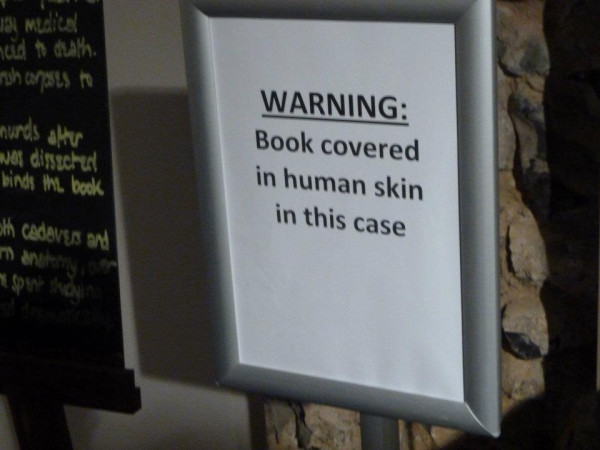

I’ve spent birthdays there, handling live leeches and drinking gin. I’ve seen Mexican miracle paintings there, verdigris mediaeval skeletons, and glass acorns for warding off lightning strikes. Once, an attendant saw how excited my friends and I were and fetched us goodie bags complete with wearable cardboard moustaches.

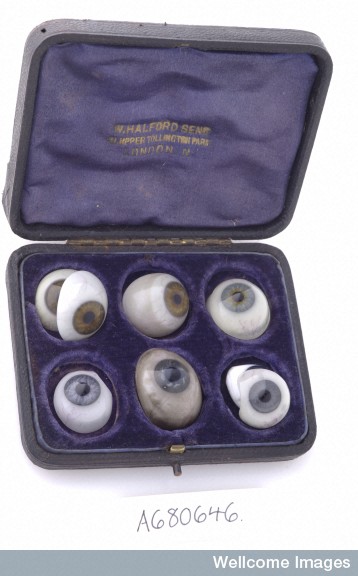

Science museums can feel unfriendly to artsy types, but at the Wellcome, the two disciplines interact. Upstairs, in the cool white Medicine Now room, slides of organs are displayed alongside barmy art (there’s a giant purple jellybaby as a metaphor for human cloning). Downstairs, in the darker, more anthropological Medicine Man room, you’ll find a wall of antique forceps and some beautifully detailed glass eyes which could easily be items of jewellery or sculpture. Plus, there’s a Bosch painting, and everyone loves a good Bosch.

But I think what I love the most about the Wellcome Collection is that, in a manner of speaking, I’m in it.

I have Marfan syndrome. The National Marfan Foundation explains:

Marfan syndrome is a disorder of the connective tissue.

Connective tissue holds all parts of the body together and helps control how the body grows. Because connective tissue is found throughout the body, Marfan syndrome features can occur in many different parts of the body.

Marfan syndrome features are most often found in the heart, blood vessels, bones, joints, and eyes. Sometimes the lungs and skin are also affected. Marfan syndrome does not affect intelligence.

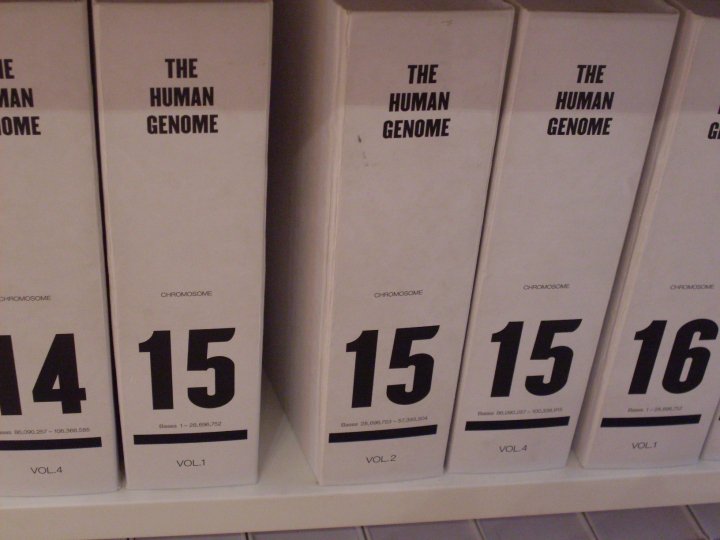

Specifically, Marfans is caused by a kink in the fifteenth chromosome. So imagine the surreal excitement I felt when I turned a corner in the Wellcome Collection and came across this:

There it is. The Human Genome Project, chapter 15, subheading ‘Verity’s Wonky Genes’. I took it from the shelf with both hands. Buried amongst the reams and reams of baffling code inside was the string of glyphs that spelled out Marfan Syndrome.

Only one in five-thousand people have Marfans. The syndrome will generally make you around six feet tall and willowy in build, with exceptionally long, spidery fingers and toes. You may have a curvature of the spine or an uneven ribcage, and you can probably bend your thumbs into strange angles. Abraham Lincoln probably had it, as did Jonathan Larson, Joey Ramone, and, I strongly suspect, Lux Interior of The Cramps.

Marfans can affect you in all sorts of strange, annoying, sometimes life-threatening ways. Individual Marfs differ. As for me, I’m well looked-after by good doctors. I pace myself, I watch my diet and try not to be a stubborn ass when it comes to clinging to the barrier at Morrissey concerts or vigorous charity shopping the weekend after minor heart surgery. (Although holding hands with Morrissey and acquiring an antique nursing chair for £10 were worth the resulting drama).

One of the things about having an unusual health problem is that you can end up feeling alienated. That’s why I love the Wellcome Collection. Things that could be clinical or morbid, like Jennifer Sutton viewing her old heart after her successful transplant, are greeted with curiosity and joy.

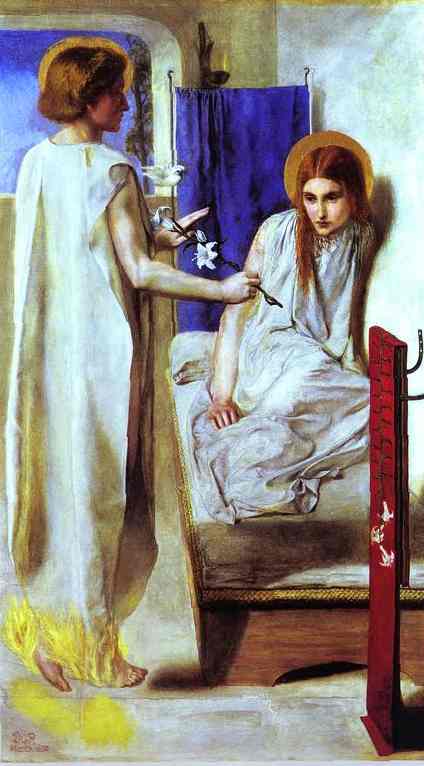

It’s an ambition of mine to get Marfans into the Wellcome more prominently. Short of standing in the entrance hall with a sign on me, I don’t know how to raise awareness. I’m not quite ready to donate my hands. But it’s a syndrome that really lends itself to art. Maybe I can use my nonexistent artistic ability to chop up my MRIs in a nice lightbox, or draw an Edward Gorey-esque bunch of spidery fingers. Or, better still, persuade someone who actually knows what they’re doing to put Marfans in front of the lens, like Alexa Wright’s ‘After Image’ series.

Where’s an artist when you need one?