If you were lucky enough to catch Doctors, Dissection, and Resurrection Men at the Museum of London, you’ll remember this fellow…

This is murderer James Legg. In 1801, the 80-year-old Legg challenged a fellow pensioner, Lamb, to a duel. When Lamb refused, throwing the pistol to the ground, Legg did the ungentlemanly thing and shot him anyway. Although apparently well-received in the courtroom, not to mention the ramifications of his advanced age and plea of insanity, Legg was sentenced to be hanged on the 2nd of November, and his body dissected.

Meanwhile, sculptor Thomas Banks and painters Benjamin West and Richard Cosway had always wondered if artistic representations of Christ’s crucifixion were anatomically correct. How they justified this is a mystery (“It’s for art, dears, art”) but surgeon Joseph Constantine Carpue apparently saw no moral issue with procuring the hanged Legg’s body fresh from the gallows and crucifying it in situ. The four men created two casts, one with skin on, one with skin off. The casts were moved to Banks’ London studio, where they attracted much attention from the curious public before being displayed for art students in the Royal Academy.

The ‘experiment’ still brings up uncomfortable questions about ownership and consent. But awfulness aside, the cast is incredible, and enormous. Legg must have been an imposing young man if he were that size at 80. The photograph is somehow more dreadful than viewing it in person. Perhaps it was the low light of the exhibition, or the woman sat at his feet, sketching, but I found it rather beautiful.

When I first set eyes on James Legg’s plaster remains and learned of his strange corporeal afterlife in the RA, I hoped Dante Gabriel Rossetti would have seen him. The student Rossetti hated drawing from sculptures in the same way most of us hated doing our times tables, but this is the boy who, dismayed by the sight of cancan dancers’ petticoats, took William Holman Hunt to a Parisian morgue to view a drowned man. On holiday. For fun. (He was a pleasant traveling companion, wrote Hunt, for certain values of pleasant.)

I think he would have loved James Legg.

Rossetti’s prolonged phase of reveling in the macabre produced some amusing works and letters: the ballad Jan Van Hunks about a smoking contest against the devil (DGR never smoked), general delight in ‘stunner’ murderesses and all things Poe. A cast of a flayed murderer would probably have persuaded him to pay more attention in class.

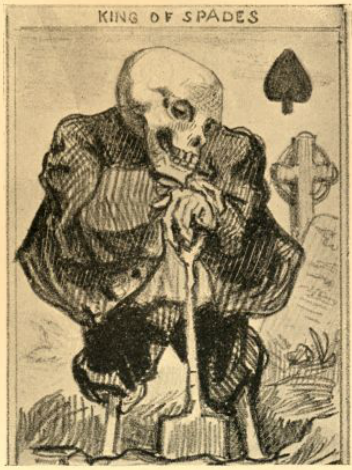

Look at this jaunty little Death, done in 1840. Note the odd leg bones. It was never meant to be a serious anatomical study, but the disregard for details is there. “I have nearly finished studying the bones,” he wrote to Mamma Francis in 1843, ” and my next drawing will most probably be an anatomy-figure.” He sounds bored to tears.

Sadly, the cast of James Legg was removed from the RA in 1822, seven years before Rossetti was born, and only returned in 1917, thirty-five years after his death, when it narrowly avoided being blown up by a zeppelin bomb.

In light of their commitment to realism and the religious nature of so many Pre-Raphaelite paintings, it is tantalising to wonder how the PRB would have reacted to such a ‘teaching aid’, had it been available.

Although Rossetti would probably argue, it doesn’t matter how accurate the cast – it’s the soul of the thing that matters.

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape?

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape? Nailed it.

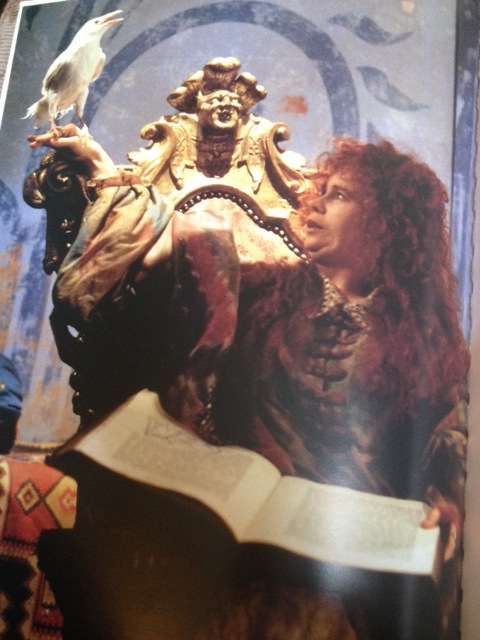

Nailed it. When the news filtered through to the mainstream press, I’d been reading about the Australian artist Vali Myers. Vali, with her trademark raccoon eyes, red haystack of hair, and tattooed moustache, is such an exciting figure, not only for her outlandish paintings and appearance, but because her chosen adornments were so intrinsic to her sense of self:

When the news filtered through to the mainstream press, I’d been reading about the Australian artist Vali Myers. Vali, with her trademark raccoon eyes, red haystack of hair, and tattooed moustache, is such an exciting figure, not only for her outlandish paintings and appearance, but because her chosen adornments were so intrinsic to her sense of self:

The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable.

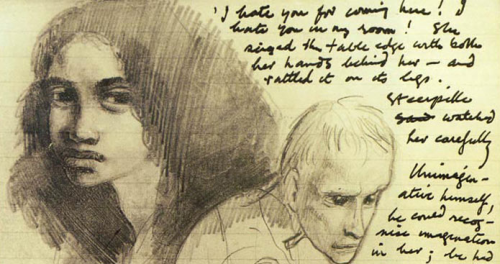

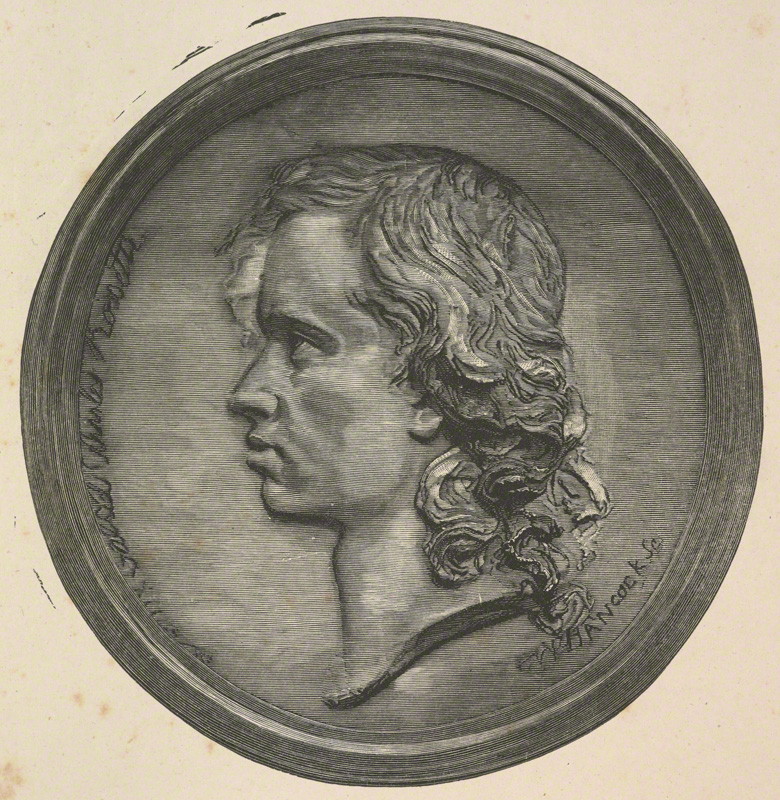

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable. Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.