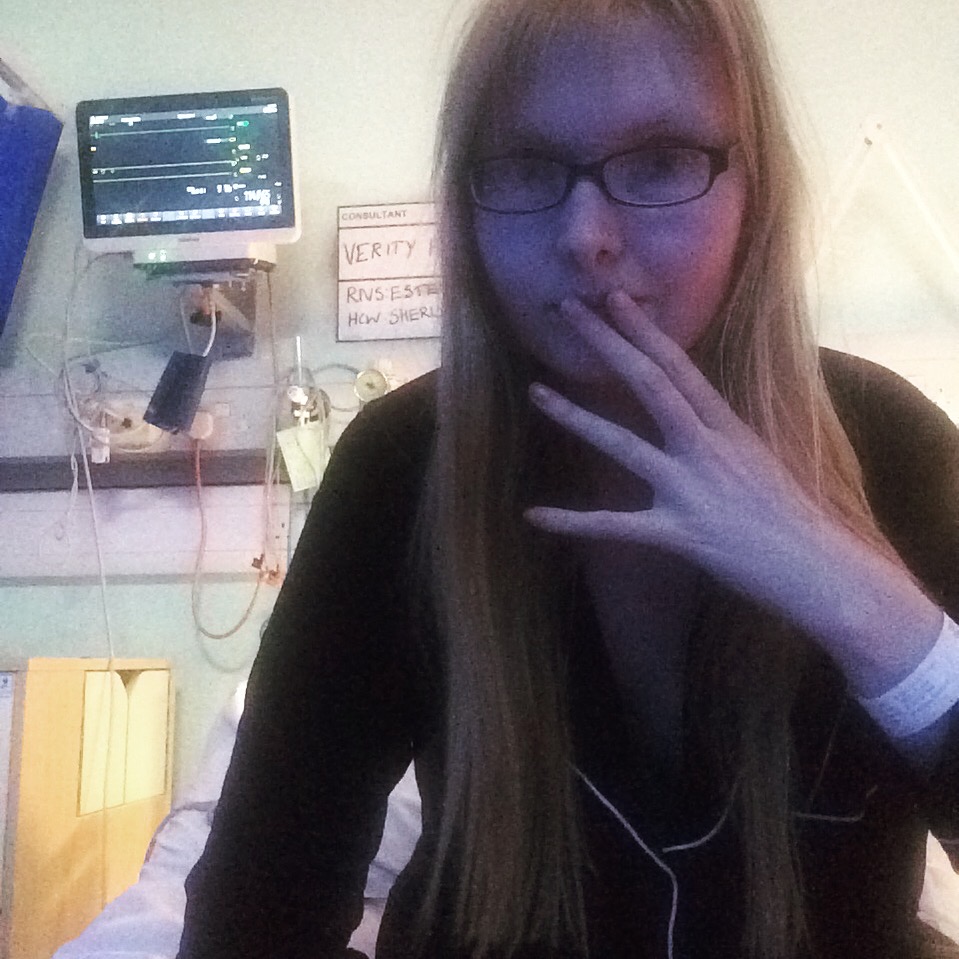

It’s been five months since my surgery, and I am still – touch wood – alive and healing. Actually, I’m feeling great. Please keep that in mind while you’re reading this!

I may have been putting this post off. When I started this series of blogs, my intention was to write a plain description of the experience to give prospective patients a clear idea of what they were going in for. But that approach comes with a lot of responsibility. The absolute last thing I want is for someone to read about my experience and think “No thanks, not today, I’ll pass if it’s all the same to you”. I don’t want to put anyone off, but I also don’t want to pretend it’s a doddle.

It shouldn’t be a shock that living with heart disease is all kinds of annoyance and misery, but I think it does need to be reiterated from time to time. As the staff nurse who greeted me as I walked into the ward said, “This is going to be rough.”

My surgery date was April Fool’s Day because of course it bloody was.

I took my big black bag with me. I wore a plain hoodie and some jeans, and took out all my piercings except my nose stud. Amazingly, they let me keep that in for the entire experience. I signed a form stating exactly what I had with me and what was being left in the hospital safe. My surgery was set for 8am the next morning as that was the slot least likely to be cancelled. Unfortunately, that meant my family were sent away and I was left alone with my thoughts all night.

My window was on the ground floor, looking out onto Papworth’s green surroundings. A little out of sight was the famous duck pond. I saw a heron fly over, seeking fish. There was a lock on the window. I looked at that lock all evening. Before bed, I was told to shower and wash my hair with antibacterial gel.

My window was on the ground floor, looking out onto Papworth’s green surroundings. A little out of sight was the famous duck pond. I saw a heron fly over, seeking fish. There was a lock on the window. I looked at that lock all evening. Before bed, I was told to shower and wash my hair with antibacterial gel.

At 10pm one of the surgeons came to see me and discuss valve options. My surgery was planned as valve-sparing, meaning I’d have my own aortic valve reattached when my new prosthetic root was in place, but because that isn’t always possible I needed to choose between a mechanical valve (meaning lifelong blood thinners to stop it rejecting) or a pig valve which could wear out within fifteen years. He explained the various pros and cons of both options, and I made a decision and signed for it. Then he outlined the really fun statistics – mortality and whatnot. With my aorta measuring 4.5cm, it was statistically more dangerous for me to be walking around than lying on an operating table. Average mortality is really, really low for aortic root replacements, even with Marfan syndrome taken into account, and the figures are actually even lower with my surgeon, Mr Nashef. He’s kind of a rockstar.

Nevertheless, it’s quite a thing to sign your name under that statistic, sitting there in your glittery slippers.

No, I didn’t sleep a single solitary wink. It wasn’t so much anxiety as my heart monitor shouting every few minutes to tell the nurse I was having ectopic beats. I told myself I’d have plenty of time to sleep the next day and settled down listening to Rammstein all night. Fight music for punching the Grim Reaper in the eye socket. Before the nurse came to take me away at 8am, I had to repeat the shower ritual and get into a hospital gown and my fancy slippers.

I was wheeled to theatre. I could have walked, but they just default to wheelchairs for some reason. I’m the kind of prisoner who jokes on the way to the gallows. Somehow the nurse and I were talking about crossword puzzles. Surprisingly, I was then held in a queue, parked up with a row of old men in identical gowns. There was one young girl, bald from chemo, but she was sent to the other side of the room. No one spoke. Staff whirled around. It was cold. I kept telling myself it would be over soon. There’s really nothing else you can tell yourself at that point.

My team introduced themselves. It takes a lot of people to replace one aortic root. I met so many people, I hardly took it in. When my two anaesthetists asked if I had any questions, and because my brain is the way it is, I blurted out something about the possibility of waking up in the middle of it all. And yes! That can happen if you have really lousy anaesthetists. Now you know. Hooray for me for asking that unbelievably stupid question at that precise moment.

I was wheeled into a small, chilly antechamber with a bed and several nurses, as well as my (not lousy) anaesthetists. Here I would be given a sedative through a cannula, followed by my general anaesthetic. I think they also attached me to some monitors in here, though my memories drift into vapour at this point. I can remember holding a nurse’s hand and saying “Just feel free to mess me up” as the drugs took hold. They do the job – you feel drunk and accepting, and full of big hilarious love. I’m pretty sure I told everyone in that room they were perfect angels. I wasn’t aware of them inserting the larger cannula that goes into the underside of the wrist, and for that I’m grateful.

I was in theatre for seven and a half hours.

I was in theatre for seven and a half hours.

I don’t remember waking up in Critical Care. I’m told one of my aunts was there to witness me first opening my eyes, and I gestured at the ventilator tube down my throat. I was worried about that part, waking up with the tube, but I don’t remember it being uncomfortable. My aunt thinks I was gesturing apologetically, as if to say “Can’t speak”. I certainly wasn’t panicking, but the nurses are prepared for that eventuality and just sedate you again if you’re a flailer. It’s rare, though. They have to leave the tube in until you can prove you can breathe without it, and though I don’t remember it being removed I know the bottom of my lungs were some of the last parts of me to wake up, so breathing is a lot like when you’re wearing a corset – upper lungs only.

When you come round, you’re on a lot of medication. It’s not like waking up from a small procedure. My family tell me I looked very peaceful and amazingly healthy, and if it weren’t for the enormous bag of spare blood and all the wires, I’d look like anyone else having a pleasant nap. From my perspective, I felt strangely immobile. I knew I couldn’t move, and though it wasn’t panic I was feeling, it was very unfamiliar. I was alive and relieved but I’d been airlifted into some new reality and yesterday was a million miles away. Slowly, very slowly, as I slid in and out of sleep, I became aware of all the things attached to me. I had tubes coming out of just about everywhere, but at that stage no pain. Weirdness, but no pain.

You’re never left alone at this early stage. I had a nurse called Rose – I think? – sitting right by my face all night, mopping my brow and comforting me. I was whispering all sorts of hoarse nonsense to her, and she just smiled and agreed with me. Another nurse was able to tell me that the girl with the bald head had got through her surgery too. I asked him to tell her I was proud of her (there’s that big hilarious love again).

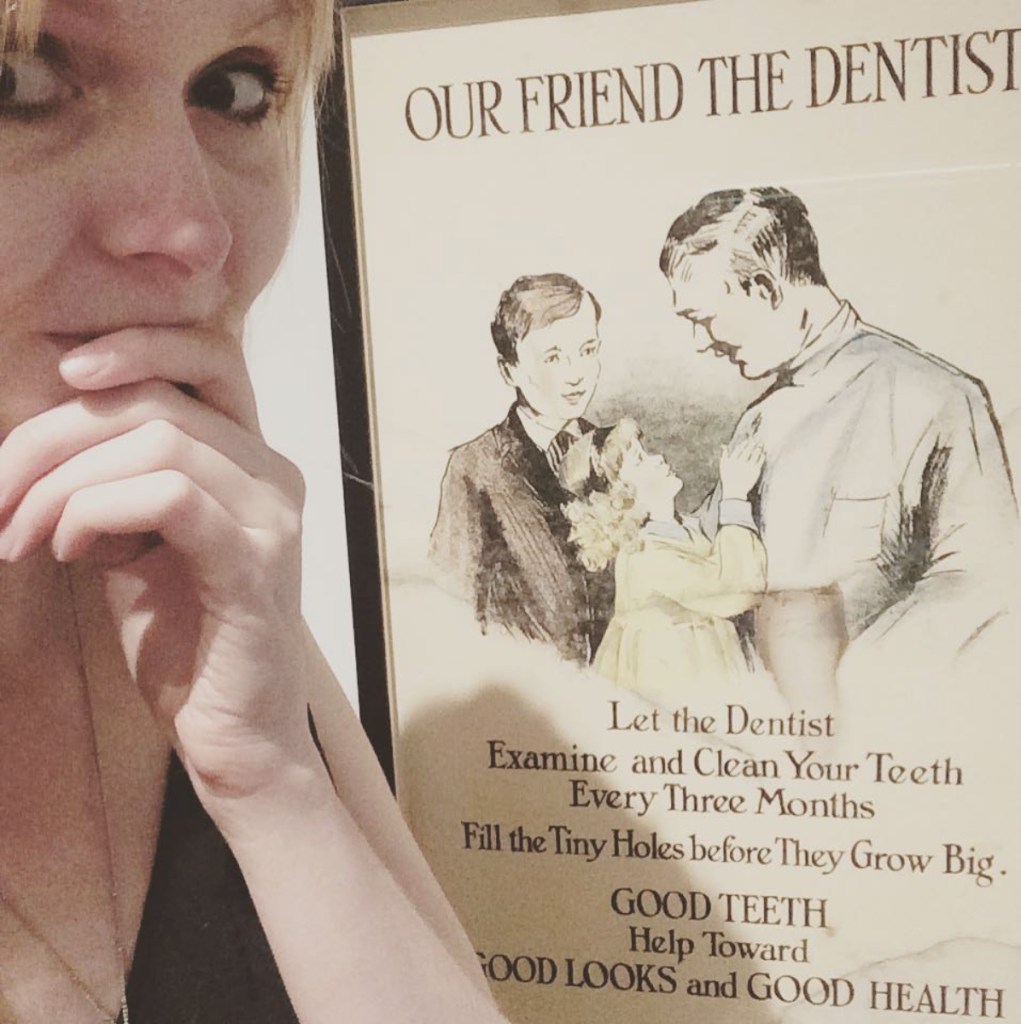

I was able to move my arms a little, but Rose brushed my teeth for me and kept my glasses clean, giving me small sips of water. I was sweating like a pig. Your body is cooled during the surgery, so when you wake up your ability to gauge temperature is completely out of whack for days or weeks. I could only speak in whispers. Every physical act was a monumental task, but at least I was in bed with nurses doing everything for me…

Hollow laughter.

Once upon a time, heart patients were kept in bed for weeks. Those days are long gone. Never mind that your feet are made of concrete and the floor is so far away you can barely dream of it, on day one you’re expected to get out of bed and into a chair. Lying still is an invitation to pneumonia and suffering is the path to enlightenment or something. It was morning, Rose had finished her shift and I had a new nurse who, honestly, I didn’t take to. While Rose had held my hand and dabbed my tears, this new nurse had had it up to here with my shit and was getting me out of that bed even if it killed me, which it quite possibly would.

After open heart surgery, your sternum is held together with internal cable ties. It is possible to break or dislodge them, so you’re forbidden to use your arms to take your own weight. Enter… The Teddy.

American hospitals give you a cute cuddly heart, but here in the NHS it’s a towel wrapped in a sheet held together with surgical tape, and yes, that’s blood you can see. I now have a Pavlovian response to the word ‘teddy’. It’s a sickening helpless fear, and I’ll probably never leave it behind. When you hear “Okay, hold onto your teddy” you know you’re about to be marched up Everest without an oxygen tank, and nothing you can do or say will get you out of it.

So there I was, clutching Teddy to my chest. The idea was I’d slowly roll onto my side and heave myself into a sitting position using the power of positive thinking. This was when I discovered my leg was all cut up. My left thigh and ankle were bandaged and stiff as a board, and I had no idea why. Wires, drains, catheters, a temporary pacemaker, something coming out of my neck, cannulas, compression socks… wriggling myself onto the edge of the bed was all about avoiding tugging on any of these things and not using my arms. Worse still, when you’re 6’3″, no piece of furniture on God’s Earth is made for your body. The chair was about ten inches too low for my body’s natural levers, so getting me on my feet and down into it was so much more terrible than it needed to be. I cannot tell you how exhausting it was. I’m getting stressed just thinking about it.

And then you’re expected to sit there. Sitting is tiring. Sitting is simply awful. I threw up. They offered me ice cream. I threw up again.

Sitting time was over, now I had to stand again. Without using my arms. From a chair so low it might as well have been a child’s.

“I can’t I can’t I can’t-”

“You can.”

“I can’t I can’t I can’t-”

“You can.”

“Don’t drop me.”

“We won’t drop you.”

Yeah, they dropped me.

I had a nurse either side of me, but I still managed to go straight back down into the chair with all the finesse of a grand piano jettisoned from a Chinook, and the whole of the Book of Revelation flashed before my eyes.

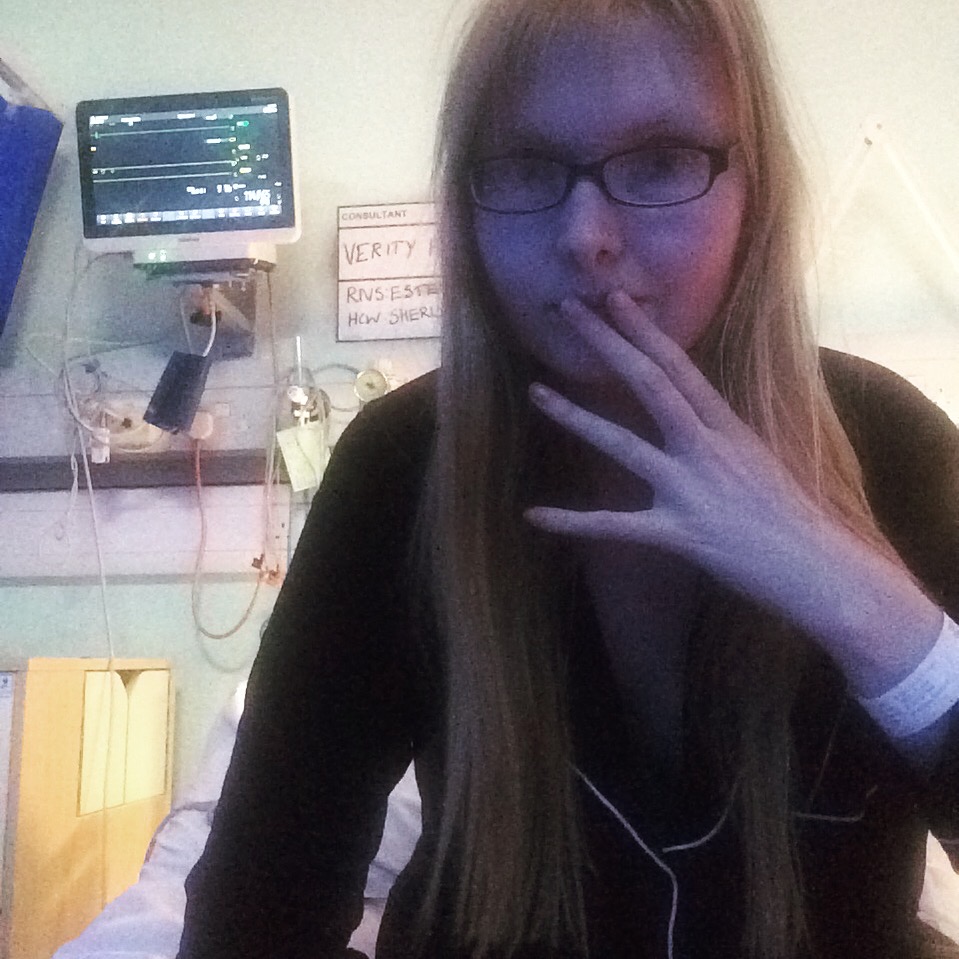

One for the ‘Gram. I’d gained a stone in water overnight. Pictured: teddy and hateful ice cream.

I stayed on Critical Care for two days. In that time, I managed to eat a teaspoon of ice cream and as many vials of liquid morphine as they would give me. Unfortunately, morphine makes me sick, so that necessitated anti-emetic drugs on top of everything. I was now in pain, yes, but it was controllable, and I was still getting intravenous dopamine, which probably helped keep me doped up enough not to care as much as I might.

Mr Nashef, my surgeon, came to visit me. I was so pleased to see his smiling face, mainly because cheerful surgeons don’t give bad news. My aortic root had been replaced with a synthetic tube as planned, and I’d been able to keep my own valve, which he’d tightened up because it was a tiny bit leaky. The only snag was that one of my coronary arteries had started to dissect and couldn’t be reattached, so I had an unscheduled bypass – known as a CABG – which explained my wounded leg. A vein had been taken from my thigh because when they tried to take one from my ankle it was no good. I’d chosen to have surgery at the right time, Mr Nashef told me. My tissue was like paper, and I wasn’t far off ‘problems’, meaning… you know.

I instantly forgot most of this conversation because I was on drugs. The merciful thing about this part is that you’ll forget most of it.

Anyway, that’s enough fond reminiscence for one day. To be continued.