I have most of my baby teeth in a box somewhere. One of them took too long to wobble its way out of my mouth, so I used my mum’s car keys to gouge it out. I was a very metal seven-year-old. One by one, they ended up under my pillow in exchange for 20p from the Tooth Fairy, who was a tightfisted little madam in my household.

I don’t really know why I still have my teeth. I keep thinking I’ll make some jewellery out of them. You can’t just bin your own bodyparts, you know? But I’ve always liked teeth. The shape, the various colours, the way they feel, like little irregular pearls. And if you have a pearl, how do you tell if it’s real? Rub it against your tooth.

Teeth and the state of them are badges of age, class, and beauty. Our first tooth may end up in a keepsake box, and our last may help to identify us after death.

At the Wellcome Collection’s recent Teeth exhibition, I got up close with Victorian dental teaching dummies like eyeless Cenobites,1940s toothpaste ads featuring cheerful squirrels, and ancient hand-cranked drills reused in the power cuts of the ’70s. What big teeth you have, grandma. It’s little wonder that, as objects, teeth take on special qualities in the anxious netherworld of folklore.

Western dream dictionaries usually say a dream of losing one’s teeth is a manifestation of the fear of losing control, whereas the Chinese interpretation is that the dream heralds a sad event in the family. But in Maori folklore, if someone grinds their teeth during sleep, it is an omen of abundance for the community. To make a child’s teeth grow and put an end to teething pains, a charm would be recited:

An eel, a spiny back,

True indeed, indeed: true in sooth, in sooth.

You must eat the head

Of said spiny back.

One 1856 source tells of another Maori charm for teeth:

Growing kernel, grow,

Grow, that thou mayest arrive

To see the moon now full.

Come thou kernel,

Let the tooth of man

Be given to the rat

And the rat’s tooth

To the man.

And then there’s tooth worms. That pain in your gums, up until the 18th century, could be explained away by the presence of evil little worms. And it isn’t surprising when so many death historical certificates will simply list ‘teeth’ as cause of death that so many people – there are accounts of this even up until the 20th century – believed hideous burrowing monsters could sneak inside their mouths. Tooth worms could be smoked out with henbane, excised with a hard poke from a literal chopstick, or just yanked out. After all, exposed nerves do look a lot like worms.

Positioning of teeth in the mouth can denote character, a la physiognomy. Norweigian folklore has it that someone with teeth packed close together will never stray far from home. The USA took it one step further, that a man with teeth overlapping would always live with his mother.

Of course, if your teeth are bothering you and you wish to ask for help from someone other than a dentist, you could take a tin effigy of your offending peg to the local church. In South America and southern parts of Europe, you may come across churches festooned with these tiny offerings in the shapes of different body parts hanging from ribbons. More folk custom than strictly Christian, the sight of scores of these glistening Milagros is something you won’t forgot.

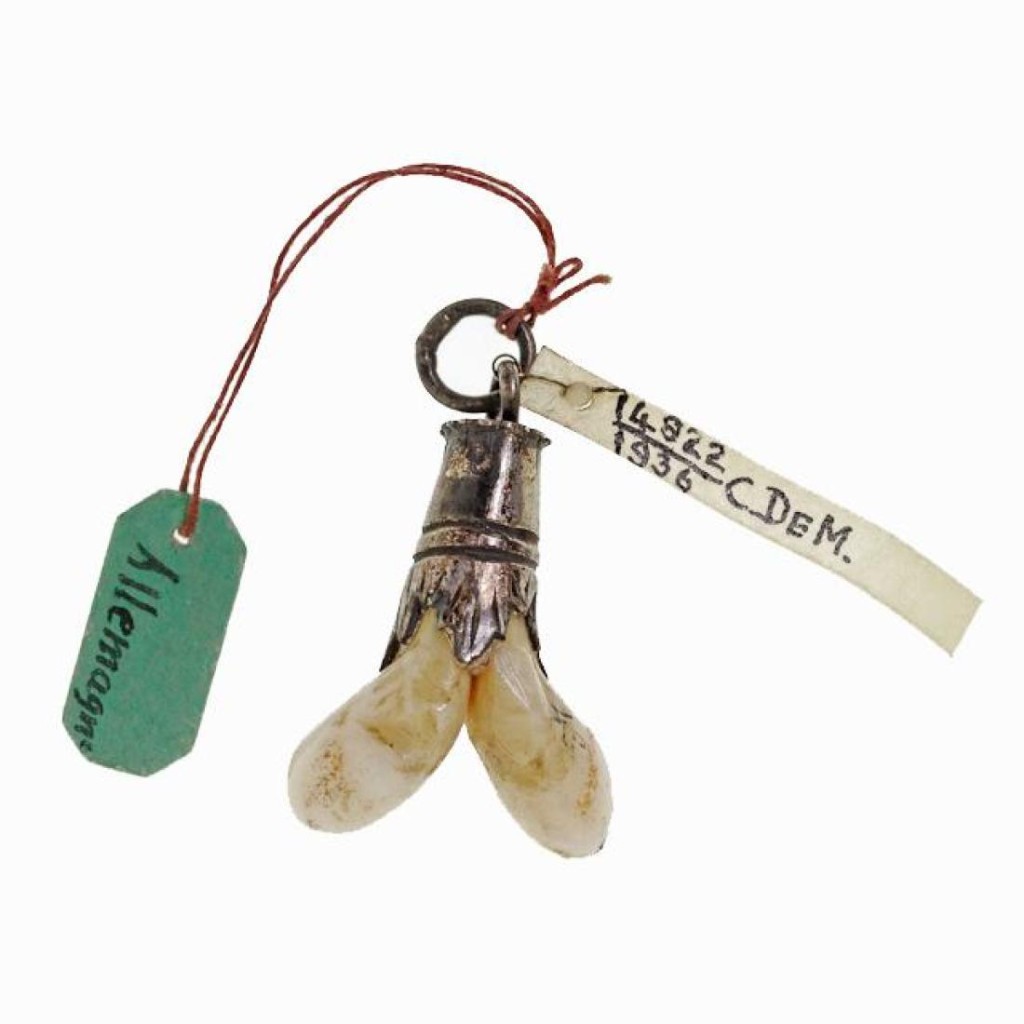

Teeth make good amulets. Queen Victoria kept a collection of tooth-set jewellery. Most of the pearly whites came from her children, but some were hunting trophies, including a gold necklace set with forty-four deer teeth, inscribed with dates of death and the words ‘all shot by Albert’. In nineteenth-century Bavaria, deer teeth on watch chains or pinned to the brim of hats were said to bring good luck to aspiring hunters.

These are a few of the toothy tidbits I collected while writing Pseudotooth. Throughout the novel, Aisling carries with her a rotted tooth she finds in her aunt’s cellar. It’s a talisman of sorts, tied to her fate as much to its previous owner’s. When we first meet Aisling, she is fully immersed in the sterile medical world. Aisling’s internal landscape is all wanderlust and scrapbook anthropology. She’s muddled; banished from her own body and her place in the world. The tooth felt like a fitting motif to take along with her. Teeth store information on our pasts. They can be weapons in times of desperation. But most of all, teeth – a single tooth – are incredibly intimate objects.

When Aisling feels the urge to tell the doctor about the witchdoctors of Tahiti who would take a shark’s tooth to release bad blood, of course, she doesn’t dare. She doesn’t exactly believe in it… but she doesn’t exactly not. Nothing in Aisling’s life is as simple as physical cause and effect. Like the tooth worms, the Milagros and the strange destiny of physiognomy, there are anxieties beneath the surface, bargains to be struck, and rhymes to be whispered when the road ahead is unclear.

Fun post, Verity! It probably won’t surprise you to know that I also kept my baby teeth, in a little gold pillbox. I remember showing them to my cousins, who were completely grossed out! Not sure what happened to them.