I love Ripper Street. It’s not so much the series as the hour of settling down with a large gin and a chat window open, howling through the experience with all of my friends. Although my bookshelf is stuffed with serial killer paraphernalia, I’m not a proper Ripperologist; the 1880s are a little late for my area of study. With Ripper Street, I can sit back and enjoy the hats.

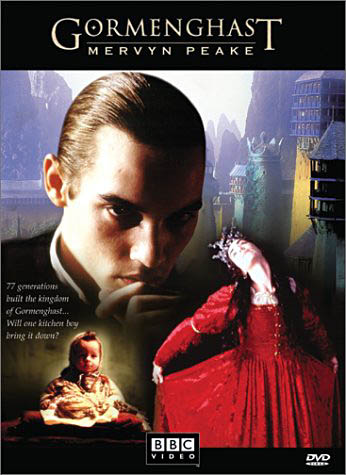

I generally hate everything the BBC comes out with. Since Gormenghast – which was my life – everything has been a let-down. But Ripper Street is gritty. Ripper Street is

intense. Ripper Street is hilarious.

M&S menswear, take heed.

The premise: it’s 1889, and Jack the Ripper has vanished. Whitechapel is still a wretched hive of scum and villainy. Policemen pose fetchingly in rat-infested alleys.

We have our surgeon. “He is…American.” Captain Homer Jackson (seriously) spends most of his time carousing with whores, loitering attractively, or interfering with cadavers in The Dead Room. He gets the loudest suits and is marginally the least violent, although he does indulge in the odd spot of torture, because the Hippocratic Oath is for sissies.

We have a skinny Jerome Flynn – who will never, ever escape his hilarious musical past*, because we simply will not allow him – as Detective Sergeant Bennet Drake. He sports Egyptian tattoos, hints at a traumatic military background, and is generally gruff, gaunt and likeable. He does a lot of clobbering. Mainly, the audience is dying to hear him break into song.

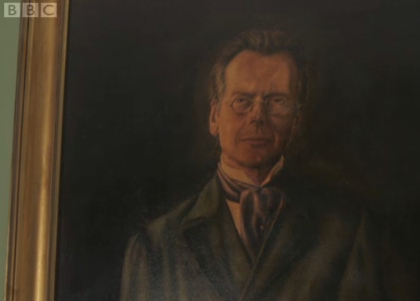

And then there’s our hero: Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. He’s a tortured maverick who believes in all sorts of rubbish, like justice, bowler hats and slow motion striding sequences. With a back etched in scars, he has a dark past, probably involving The Ripper whom he spends most of the time dwelling on. In his office, where he chats to the relatives of murdered women, there is a collage of post-mortem Ripper victim photographs. He’s sensitive, but not that sensitive.

There’s some hoo-ha about his lost child, but by episode three, the audience still don’t care.

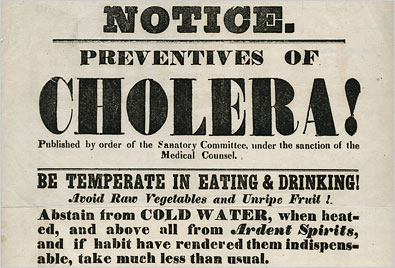

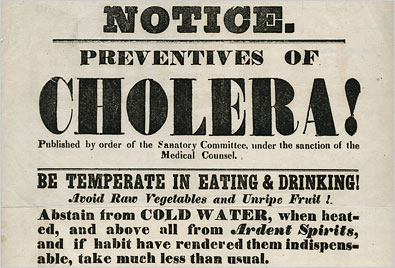

So far, Ripper Street has gone through the gritty Victorian drama checklist. We’ve had early snuff films, molly houses, cholera (or is it…?), gangs of loveable urchins, and ‘ores galore. That leaves babies in handbags, and vampires.

Sometimes, Stephen King turns up:

And sometimes, this sort of thing happens:

Special mention goes to this guy: the tattooed, crucifix-festooned Scouser Carmichael. He creates total chaos in episode two by simply arriving. My partner, being from Lancashire, has much the same effect in London by making eye-contact on the Tube.

As for the writing, I quite like it. There are some screechingly funny lines. (“Reid, every man likes a good cabinet, but is this quite the time?”) The interactions between the three leads are on the intense end of natural, except when Reid launches into one of his speeches about justice whereupon everyone awkwardly averts their eyes. You get the feeling Drake keeps a picture of Reid under his pillow. Homer is your typical American archetype, but the BBC wanted to export the series, so what can you do?

I’m just going to lie here, being sad, if that’s alright with you.

There aren’t many women in Ripper Street. Those we do see are either dead or in some kind of trouble spewing from the fount of all woe: the uterus. Mrs Reid, played by Amanda Hale, has a missing or dead child and copes by doing vague charity work for needy ‘ores with ‘earts of gold. Hale was much more interesting in The Crimson Petal and The White, cutting her dresses into hundreds of tiny birds and stabbing her own feet with a garden spade. I live in hope of a female character I can truly sympathise with, but I’m not holding my consumptive breath.

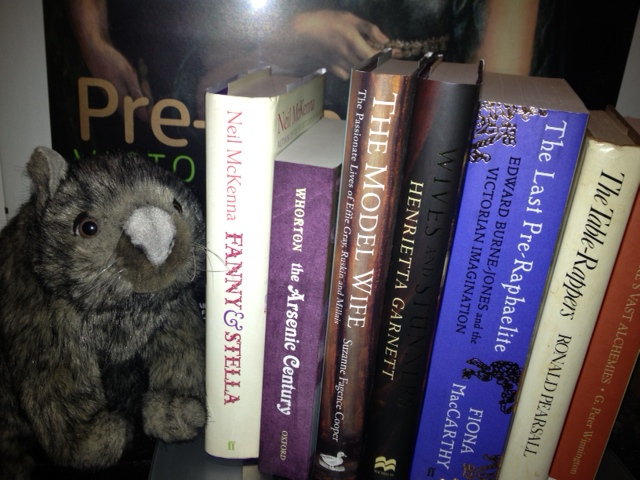

I blu-tacked this to the inside of the toilet door in my student accommodation. That’s how I approach friend-making.

I know I’m enjoying Ripper Street for all the wrong reasons. I know it’s not entirely normal to rejoice when you hear there’s been an outbreak of cholera, or to find yourself hoping the parish priest has been on an urchin-strangling spree because it’s Sunday night and you’re in the mood for a good ‘anging. But this is as close as I’m going to get to a soap opera aimed at my demographic. And the hats are awfully nice.

Catch up on the hilarity with iPlayer, or tune in to BBC1 on Sundays at 9pm.

Not everyone enjoyed Unchained Melody.

* When I was nine, my parents gave me a Robson and Jerome tape because I was hugely into Elvis Presley (an interesting leap of logic), so the sight of Jerome Flynn putting a poisoner into an armlock is hysterically funny.

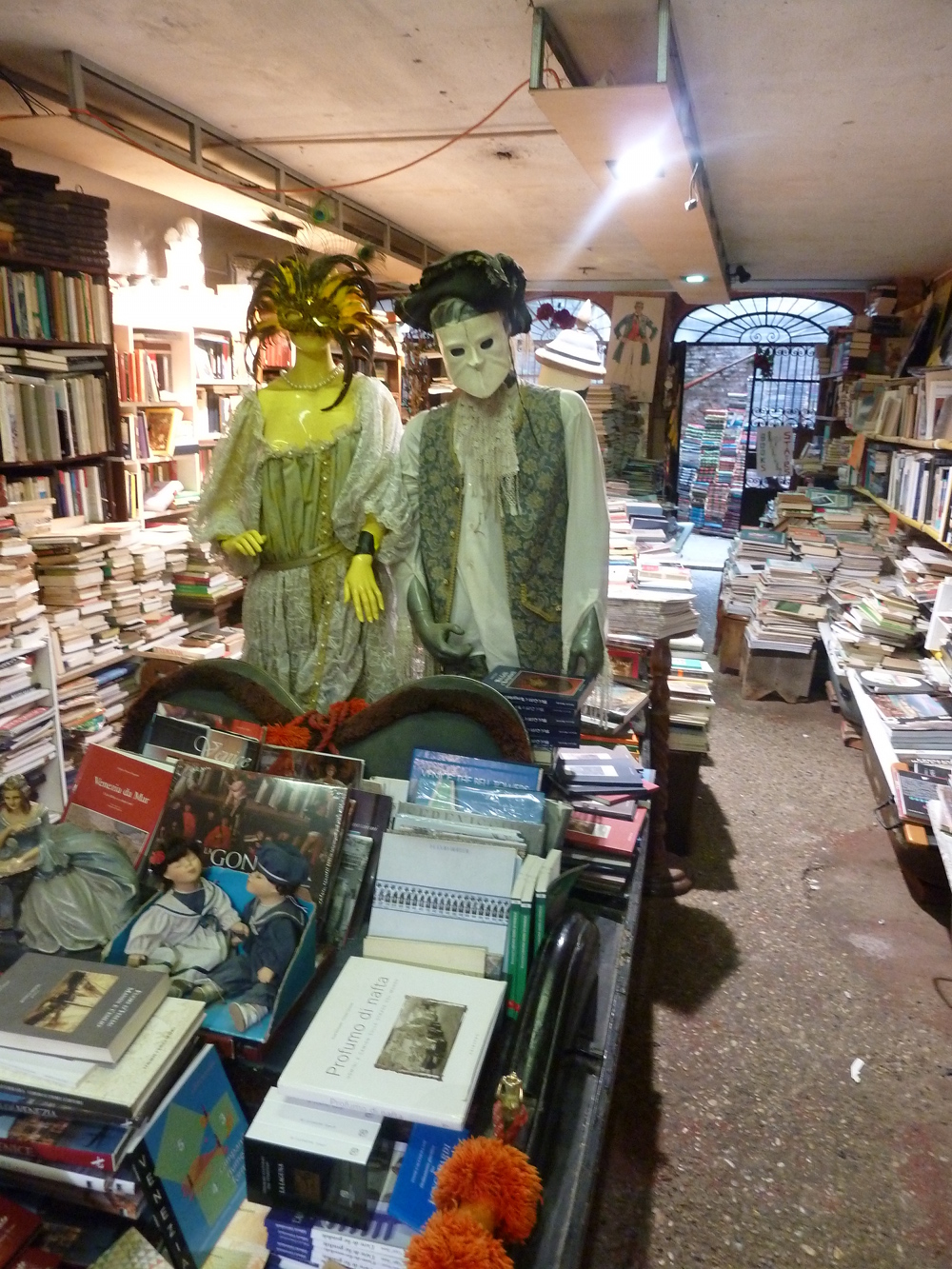

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape?

I know what you’re thinking. Where’s the fire escape? Nailed it.

Nailed it.

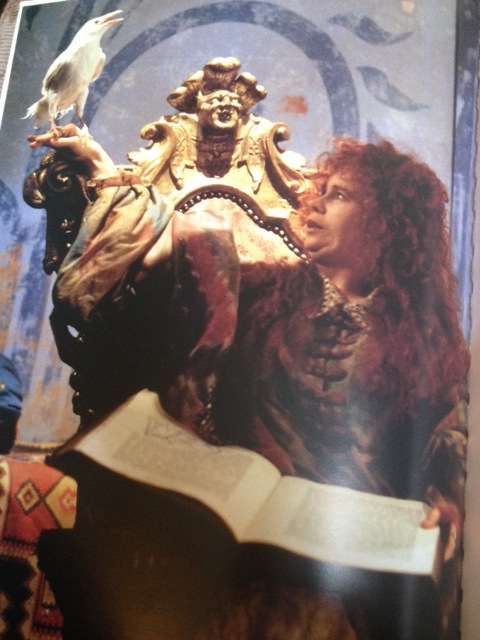

When the news filtered through to the mainstream press, I’d been reading about the Australian artist Vali Myers. Vali, with her trademark raccoon eyes, red haystack of hair, and tattooed moustache, is such an exciting figure, not only for her outlandish paintings and appearance, but because her chosen adornments were so intrinsic to her sense of self:

When the news filtered through to the mainstream press, I’d been reading about the Australian artist Vali Myers. Vali, with her trademark raccoon eyes, red haystack of hair, and tattooed moustache, is such an exciting figure, not only for her outlandish paintings and appearance, but because her chosen adornments were so intrinsic to her sense of self:

The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable.

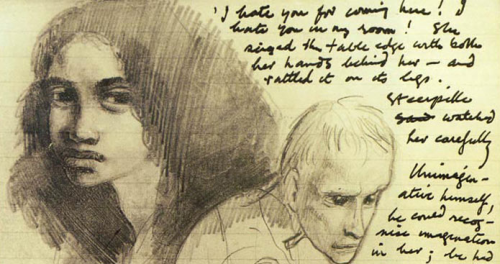

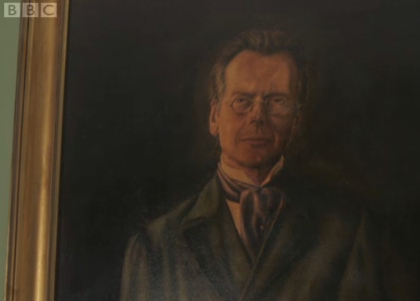

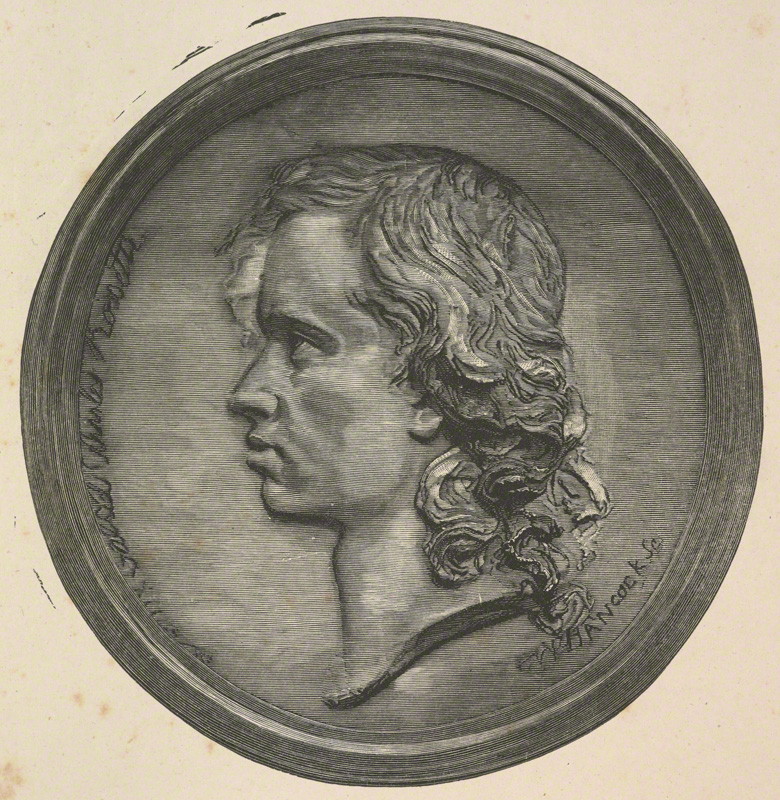

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable. Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.

Sculptor John Hancock’s 1846 plaster medallion is the earliest known likeness of Rossetti in adulthood. This is the young, dreamy Gabriel Hunt and Stephens remembered shirking classes at the Royal Academy: 18, girlish and moody, with unbrushed ‘elf locks’, and an insouciant air masking rickety self-confidence. Always surrounded by what Hunt called his ‘following of clamorous students’, the adolescent Gabriel wore his poverty with bravado: if you took exception to his unfashionable, mud-spattered clothes, well, you obviously didn’t have a poet’s soul.