I love this part.

The Mighty Healer: Thomas Holloway’s Victorian Patent Medicine Empire will be published in winter 2016 by Pen & Sword.

The Mighty Healer: Thomas Holloway’s Victorian Patent Medicine Empire will be published in winter 2016 by Pen & Sword.

I was in Bury St Edmunds this week, taking a breather from writing The Mighty Healer. I’m immersed in research about Bedlam lately, and there’s only so many times one can read the phrase ‘urine-soaked straw bedding’ before depression sets in. So I thought I’d take a break and return to my comfort zone: hideously brutal martyrdoms.

I photographed this statue of Saint Edmund outside Bury cathedral. In recent years, the interior has been restored to its colourful medieval self, all sky blues and reds and golds, like something a child might paint. The nearby abbey was badly hit during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries – only a few romantic ruins remain – but the site was once a popular pilgrim destination: the shrine of Saint Edmund, martyr king of England.

Edmund was the king of East Anglia during the 9th century. Now the patron saint of wolves, pandemics, and victims of torture, Edmund’s feast day – the 20th of November – marks his death at the hands of Ivar The Boneless during the Viking invasion of England. He is considered by some to be the true patron saint of England. In fact, he was until 1348 when he was officially replaced by St George, presumably because an armour-clad hunk thrusting a spear through a dragon is a more respectable national emblem than a weed with a bowl-cut meekly accepting a beating from a gang of Danes.

Edmund was the king of East Anglia during the 9th century. Now the patron saint of wolves, pandemics, and victims of torture, Edmund’s feast day – the 20th of November – marks his death at the hands of Ivar The Boneless during the Viking invasion of England. He is considered by some to be the true patron saint of England. In fact, he was until 1348 when he was officially replaced by St George, presumably because an armour-clad hunk thrusting a spear through a dragon is a more respectable national emblem than a weed with a bowl-cut meekly accepting a beating from a gang of Danes.

St George being of Greek/Palestinian blood, he doesn’t make an awful lot of sense as Patron saint of England beyond the ‘slaying things is wicked cool’ angle. There’s a campaign to reinstate St Edmund; I met a few of the supporters in 2006, just before Parliament rejected their petition to bring him back. They’re still going, if you’re interested.

After killing Edmund, the Vikings managed to erase almost all contemporary evidence of his reign. We really know very little about the man, but Anglo-Saxons being Anglo-Saxons, we have some nice accounts of his death…

“King Edmund, against whom Ivar advanced, stood inside his hall, and mindful of the Saviour, threw out his weapons. Lo! the impious one then bound Edmund and insulted him ignominiously, and beat him with rods, and afterwards led the devout king to a firm living tree, and tied him there with strong bonds, and beat him with whips. In between the whip lashes, Edmund called out with true belief in the Saviour Christ. Because of his belief, because he called to Christ to aid him, the heathens became furiously angry. They then shot spears at him, as if it was a game, until he was entirely covered with their missiles, like the bristles of a hedgehog (just like St. Sebastian was).

When Ivar the impious pirate saw that the noble king would not forsake Christ, but with resolute faith called after Him, he ordered Edmund beheaded, and the heathens did so. While Edmund still called out to Christ, the heathen dragged the holy man to his death, and with one stroke struck off his head, and his soul journeyed happily to Christ.”

– Ælfric of Eynsham, Old English paraphrase of Abbo of Fleury, ‘Passio Sancti Eadmundi’.

Ivar had Edmund’s severed head thrown into the woods. Edmund’s followers searched for him, calling out “Where are you, friend?” the head answered, “Here, here,” until they found it, clasped gently between a wolf’s paws. The villagers then praised God and the wolf that did His work. It walked tamely beside them before vanishing back into the forest.

Ivar had Edmund’s severed head thrown into the woods. Edmund’s followers searched for him, calling out “Where are you, friend?” the head answered, “Here, here,” until they found it, clasped gently between a wolf’s paws. The villagers then praised God and the wolf that did His work. It walked tamely beside them before vanishing back into the forest.

The 14th century poet John Lydgate called the “precious charboncle of martirs alle”. If you believe Lydgate, Edmund performed dozens of miracles after his death, including setting fire to an uncharitable priest’s house, materialising before the Danish King Sweyn and stabbing him with a spear (because you would, really, wouldn’t you?), and my favourite, catching a Flemish pilgrim in the act of stealing jewels from his shrine whilst pretending to kiss it. Edmund miraculously glued the pilgrim’s lips to the shrine until he apologised.

Right! Back to Bedlam.

On the morning of July the 14th 1789, the people of Paris had had enough. The medieval fortress Bastille, a symbol of the abuses of the monarchy, was stormed by a mob of a thousand men, women, and children. The garrisoned guards, sympathetic to the cause, joined the vainqueurs, helping to free the Bastille’s prisoners (all seven of them, including one chap who thought he was Julius Caeser). Ninety-eight attackers were killed. The Bastille’s governor was beheaded after kicking a pastry cook in the groin. It was the flashpoint of the Revolution, a pivotal moment in Europe’s history.

For Gaetano Polidori – father of The Vampyre‘s John Polidori and grandfather of Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti – the rise of the people against the injustices of poverty and monarchy really put a dampener on his morning stroll.

“I was passing by the Palais Royal while the populace were running to assault the fortress; and, having encountered a highly-powdered wig-maker, with a rusty sword raised aloft, I, not expecting any such thing, and hardly conscious of the act, had the sword handed over to me, as he cried aloud—‘Prenez, citoyen, combattez pour la patrie.’ I had no fancy for such an enterprise; so, finding myself sword in hand, I at once cast about for some way to get rid of it; and, bettering my instruction from the man of powder, I stuck it into the hand of the first unarmed person I met; and, repeating, ‘Prenez, citoyen, combattez pour la patrie,’ I passed on and returned home.”

In summary: “Screw you guys, I’m going home.”

As always, at moments of great historical significance, you have bystanders who’d really rather be at home with a cup of tea.

The Rossetti link to the Bastille doesn’t end there. I’ve already blogged about Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s youthful trip to the site of the Battle of Waterloo with fellow Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt. While the battlefield with its meddlesome tour guides left DGR distinctly unimpressed, the site of the Bastille was far more stirring. In October 1849, he wrote home to his brother William:

The other day we walked to the Place de la Bastille. Hunt & Broadie smoked their cigars, while I, in a fine frenzy conjured up by association and historical knowledge, leaned against the Column of July and composed the following sonnet:

How dear the sky has been above this place!

Small treasures of this sky that we see here

Seen weak through prison-bars from year to year;

Eyed with a painful prayer upon God’s grace

To save, and tears which stayed along the face

Lifted till the sun set. How passing dear

At night, when through the bars a wind left clear

The skies, and moonlight made a mournful space.

This was until one night, the secret kept

Safe in low vault and stealthy corridor

Was blown abroad on a swift wind of flame.

Above God’s sky and God are still the same:

It may be that as many tears are shed

Beneath, and that man is but as of yore.

As someone who thoroughly enjoyed The Castle of Otranto, you can see how, on balance, Rossetti would prefer the sort of battle that involved ghastly dungeons and the tears of the damned. Revolution, of course, was a cause close to the hearts of the PRB, though perhaps, as this hasty sonnet suggests, it was the sentiment of revolution and not the act itself that lent itself to art.

As it’s the two-hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, I thought I’d share this Pre-Raphaelite tidbit from the twenty-one-year-old Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

In the autumn of 1849, he and William Holman Hunt took a holiday to the continent together. Rossetti journaled the experience in verse which he duly sent to his brother, William Michael, back in London. Between sniggering in art galleries and noticing pretty girls (French ones weren’t as nice as English ones, naturally), the PR Brothers took in the usual famous attractions, including the site of the Battle of Waterloo. Here’s what Rossetti thought of it:

On the Field of Waterloo.

So then, the name which travels side by side

With English life from childhood—Waterloo,

Means this. The sun is setting. “Their strife grew

Till the sunset, and ended,” says our guide.

It lacked the “chord” by stage-use sanctified,

Yet I believe one should have thrilled. For me,

I grinned not, and ’twas something:—certainly

These held their point, and did not turn but died:

So much is very well. “Under each span

“Of these ploughed fields” (’tis the guide still) “there rot

Three nations’ slain, a thousand-thousandfold.”

Am I to weep? Good sirs, the earth is old:

Of the whole earth there is no single spot

But hath among its dust the dust of man.

Oh dear. But he does have a point. And then, in a letter to William at home:

One of the great nuisances of this place, as also at Waterloo, is the plague of guides from which there is no escape. The one we had at Waterloo completely baulked me of all the sonnets I had promised myself; so that all I accomplished was the embryo bottled up in the preceding column. Between you and me, William, Waterloo is simply a bore.

This Saturday, the 13th of June 2015, All Saints Church on Jesus Lane will be open to the public from 11.00am to 3.00pm.

Building started on site in 1863 where no former church existed. Instead of a mishmash of different ages like most medieval churches, All Saints is a testament to the vision of one man, George Fredrick Bodley, one of the most significant architects of the Gothic Revival.

With the artistic input from William Morris, Charles Eamer Kempe, Edward Burne-Jones, Ford Maddox Brown, Frederick Leach and Philip Web, there are plenty of stories to tell. Volunteers will be on hand to guide you around the church’s intricate details, including the pre-WW1 graffiti in the chamber to the right of the altar.

Friends of All Saints are always looking for more volunteers. Opportunities include being part of an advisory forum, research, events and fundraising. Email Karen Fishwick for more details: kfishwick@thecct.org.uk

2015 is off to a busy start. I’m very pleased to say I’ve been commissioned by Pen & Sword to write a book on Thomas Holloway, my Victorian ancestor, who made his fortune with patented pills and ointments.

It’s due for publication in 2016, so I’ll be spending most of this year poring over material like this…

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–

I’d like to be able to write coherently about the British Library’s Gothic exhibition, but because I’m an inveterate goth, I’m at risk of listing my moments of “Oh God, I can’t believe they’ve got the actual original [insert artefact here]”, hand to pale brow. Bear me for a moment, because–

Mervyn Peake’s handwritten Gormenghast!

Doctor Dee’s Elizabethan scrying mirror!

Thomas Chatterton’s medieval forgeries!

Letters by John Polidori!

Not since 2012’s Pre-Raphaelites at The Tate have there been so many of my favourite things in a single room. Anyone who loves Gothic will lick their chops at The British Library. From the genre’s florid beginnings with The Castle of Otranto to The Sisters of Mercy crooning at girls who wander by mistake, the exhibition is a celebration of the pleasure Gothic’s many incarnations have brought people down the centuries – and how Gothic manages never to die.

Crumbling ramparts, impenetrable forests, double lives, and lashings of gore. Gothic has always toyed with what disturbs us – the secret lives of respectable personages in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, female sexuality in Carmilla, foreign invasion in Dracula. No wonder there was pearl-clutching at the thought of sensible Victorian girls devouring Gothic novels, letting their darkest desires run free. This breathless consumption of all things dreadful left early Gothic fans open to ridicule (try reading The Castle of Otranto without laughing), but the exhibition manages to convey Gothic’s steady evolution into a self-aware, perhaps even post-modern genre, taking us through to Edward Gorey’s playful macabre and the androgynous world of post-punk goth.

The hysterical quality of Gothic is where the fun lies. Because there’s that veneer of ‘wink-wink, we know this is daft’, the genre has the opportunity to introduce genuinely scary ideas in a setting we’re already comfortable with. We sign up to the horror of Gothic while we may shy away from brutal realism. Take the alcoholism and child abuse in The Shining. We talk about the bathtub woman or the bloody lift, but what’s really chilling is Jack’s likability while he terrorises his wife and child with a croquet mallet. Gothic is something that lurks beneath the ordinary; a sense of heightened, oversaturated reality where the family secrets are literally locked in the attic, scratching with broken fingernails at all that floral Victorian wallpaper.

Terror & Wonder is on at the British Library until January 2015.

My short story, Cremating Imelda, is published in Animal Literary Magazine this month. Imelda, a modern hermit in an abandoned village on the Norfolk coast, is a woman with a morbid talent concerning food – and mortal sin.

This is an old fascination of mine: the links between death, what we eat, and why.

For centuries, sin-eating was a funerary tradition grudgingly tolerated by The Church. Usually a reviled individual on the edge of society, the sin-eater went to funerals and ate bread or cake off the coffin, absorbing the deceased’s sins and thus allowing them to speed through purgatory. Presumably, they hoped someone would do the same for them, when the time came.

Sin-eating has long fallen out of favour. But there are more recent funerary traditions involving food that still manage to make us uncomfortable. A childhood memory: a Greek holiday. I was permitted one treat; anything I chose from the bakery. This bakery was nothing like the ones in England. There wasn’t a single stodgy pink bun or unhappy gingerbread man. Every confection was a miniature ornament sprinkled with green pistachio, or shining with honey. But what I wanted was inside a glass cabinet. A dish piled with plain brown biscuits. Just flat brown rounds of dough – nothing to excite a child. Perhaps it was because they were behind glass and therefore forbidden. I knew what I wanted, and I asked for it.

“Those are not for little girls. Those are for… for…” The baker wheeled her hands, searching for the English. “The funeral.”

Get the child away from the death biscuits. This was a Greek custom, the baker told us. Sweets to eat in the presence of the dead. Looking at the mountain of biscuits, I remember thinking the locals must have been dropping like flies. I ended up with some unmemorable cake or other, and the episode went down as further proof that Verity always was ‘a grimly kid’ (to borrow Rossetti’s phrase). But the idea of funeral biscuits fascinated me. Why didn’t we do this in England?

Food has become the awkward aftermath of the funeral service. I find myself in church hall kitchenettes, spending a great deal of time nibbling dismal supermarket own-brand Jammie Dodgers because it gets me out of talking to anyone. I’ve already stipulated I want gin served at my funeral, partly because everyone secretly hates those undersized cafeteria cups of tea, and also because I think a funeral is a place for a sort of human communion. “Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me.”

The Nourishing Death blog is a brilliant resource for anyone interested in the ways people all over the world honour their dead with food. Because food, in a ritual setting, is communication. In Funeral Festivals in America, Jacqueline S. Thursby writes of the funeral biscuit’s role in the Victorian way of death in the USA’s Pennsylvania:

…a prevailing funeral custom was that a young man and young woman would stand on either side of a path that led from the church house to the cemetery. The young woman held a tray of funeral biscuits and sweet cakes; the young man carried a tray of spirits and a cup. As mourners passed by, they received a sweet from the maiden and a sip of spirits from the cup furnished by the young man. A secular communion of sorts, these were ritual behaviors that transcended countries of origin and melded a diverse young nation with the common cords of death, mourning, and tradition. The funeral biscuit served as part of a code representing understood messages of mourning, honor, and remembrance.

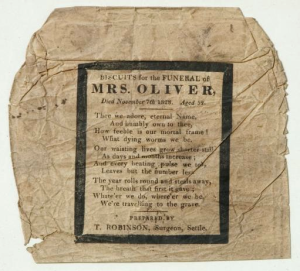

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

In England, packaged up in paper and sealed with a blob of black wax, funeral biscuits came in many different flavours and shapes. Sometimes the packages bore morbid little poems, practically gallows ballads. One of these is in the Pitt Rivers museum. Biscuits for the funeral of Mrs Oliver, died November 7th 1828, aged 52:

Thee we adore, eternal Name,

And humbly own to thee,

How feeble is our mortal frame!

What dying worms we be.

All flesh is grass. Enjoy your biscuit.

It’s little wonder such unflinching morbidity is unwelcome in the sanitised funerals of the modern world. But many European cultures still hold on to the funeral biscuit. In 2011, a Greek family were accidentally fed cocaine-sprinkled funeral biscuits, leading to what sounds like a lovely service:

The elderly bystanders, instead of mourning, began to dance around the dead, and the tears turned to nervous laughter. The cognac was consumed in shots accompanied by the sound of happy toasts, and there were some who started ordering mojito cocktails.

So what do you have planned for your send-off? If you could have a sin-eater come to wipe away your deeds, would you?

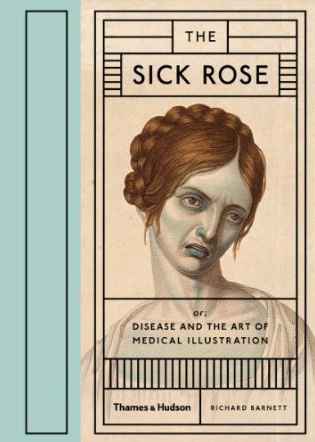

The Sick Rose: Or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration

The Sick Rose: Or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration

– William Blake

In a pub a few weeks ago, a doctor friend was telling me about his first autopsy. What stayed with him, he said, was how the surface brutality of the act was accompanied by a strange, palpable tenderness as the assembled students protected the face of the deceased, keeping it clean and untouched. I thought of this when reading Dr Richard Barnett’s new book, The Sick Rose, ‘a visual tour through disease in an age before colour photography’. These painstakingly detailed images, so much more intimate than a quick photo session for The Lancet, take on the task of showing human bodies at their most vulnerable while also communicating something of the subject’s soul. Even affirming it, in the face of what was – at least then – helpless suffering.

In case it comes as a shock, I love the history of medicine. Being a) a medical oddity myself, and b) from a family of doctors who refused to censor their conversation at the dinner table, I’m always up for a chat about the experimental origins of rhinoplasty or how best to suspend a foetus in lucite. I’ve been looking forward to this book for months, especially as I went on a London gin tour with Dr Barnett a couple of years ago, and if it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t have known about the 18th century gin-dispensing cat. That’s the kind of thing I need to know.

And have I mentioned the contents of my living room?

I was always going to love The Sick Rose. Physically, it’s gorgeous. A heavy, tactile hardback. Even the endpapers are smallpox, and the clinical, geometric cover design contrasts sharply with a portrait of a wasted young Veronese woman, blue with cholera. Thought has gone into the aesthetic, and it doesn’t go down any of the obvious ghoulish routes, making the reader uneasy from the off. Is this art or science? Is there a line dividing the two?

That’s what I like about the book. It’s unflinching but compassionate. The images of sores, growths, pestilence, and dissection are shocking without being childish. You’re invited to look into these faces and wonder who they belonged to. One particularly moving page features a baby wizened with syphilis, staring past the reader with ancient eyes.

And then there’s the human ingenuity. Silver noses for patients disfigured by venereal disease, or beautiful art nouveau posters warning against ‘the white death’, a poetic and oddly desirable pseudonym for TB. Even my Uncle Thomas Holloway makes an appearance, with his delicate ceramic pots of useless ointment, bearing the image of Britannia and her shield. Disease and death are inseparable from the human condition, so it’s natural we should turn to art for expression and protection.

And then there’s the human ingenuity. Silver noses for patients disfigured by venereal disease, or beautiful art nouveau posters warning against ‘the white death’, a poetic and oddly desirable pseudonym for TB. Even my Uncle Thomas Holloway makes an appearance, with his delicate ceramic pots of useless ointment, bearing the image of Britannia and her shield. Disease and death are inseparable from the human condition, so it’s natural we should turn to art for expression and protection.

These symbolic gestures are not always comforting. For medieval physicians, leprosy was a sign of moral degradation, and the rituals that followed are disturbing. Barnett writes: “[Leprosy was] not only a disease but also a metaphor for the frail state of the human soul, portending the foulness of the grave and the agonies of purgatory. Some Catholic communities developed ceremonies in which lepers were declared symbolically dead, excluded from communal Christian life, even made to lie in a grave while a priest recited a burial mass”.

Compassionate. One can’t help but look at the recent cultural resurgence of zombies and feel queasy. Can such things only appeal to us when we’re comfortably removed from the possibility of actual living death? And what does it say about us?

Philosophical reflections aside, the most unsettling thing I learned while researching The Sick Rose was that the makers of the game series BioShock based the faces of the splicers (drug-crazed mindless killers, if you haven’t played) directly on those of disfigured WW1 servicemen. There’s an essay on it here by Suzannah Biernoff – upsetting reading, and something I’m astonished isn’t more widely known. BioShock is one of my favourite shoot-em-ups, but I’d never made the mental link until Biernoff pointed it out. These ‘points of contact and dissonance’ between art, entertainment, and anatomy too often tread the problematic line of appropriation. It needs examining, and The Sick Rose is refreshingly mindful of this.

In short, I’m recommending the book to everyone. It’s beautiful and emotionally-engaging. All the while the ravages of disease and cultural ideas of monstrosity go hand in hand, thoughtful books like The Sick Rose are still very much needed. It’s natural to be fascinated by the blood and horror of the past, but it’s important to temper that fascination with the humanity of the subject. We mustn’t forget how relatively fortunate we are today.

I’m obsessed with History’s drama series, Vikings. I only started watching because I enjoy a bit of the old ultraviolence, but now I’m emotionally involved to an embarrassing degree and spend my time praying for Athelstan’s safety. That poor child has been through enough. All the hacking and slashing has piqued my interest, but, as fans of the show have pointed out, Vikings is only tenuously based on real events. We visited The British Museum’s wildly popular new exhibit – Vikings: Life and Legend – to learn more.

Were the Vikings one gigantic black metal band, or a culture as nuanced and refined as any other? Life and Legend doesn’t try to force you into either camp. What it does do is present the way the Northmen interacted with the cultures they encountered – the Franks, the Slavs, the Anglo-Saxons and beyond – and the evidence isn’t always what most visitors are expecting. Surviving poems prove it wasn’t all about violent conquest:

What’s this talk of going home?

My heart is in Dublin,

And the women of Trondheim won’t see me this autumn.

The girl has not denied me pleasure-visits, I’m glad;

I love the Irish lady as well as my young self.

– Magnus ‘Barelegs’ Olafsson, king of Norway (11th century)

These and other fragments challenge the image of the Viking people as marauding beasts. Sometimes they feel strangely familiar. Take, for instance, this public health announcement:

A man shouldn’t clutch at his cup, but moderately drink his mead.

A thousand years on, and Europe still isn’t listening.

However, if it’s indiscriminate bloodshed you’re after, there’s a lot to take in. We handled a 10th century axe-head, which the attendant helpfully informed us “was for killing people”. Then there was the absolute cutting-edge of weapon technology: Ulfberht swords. So powerfully made and sought-after were Ulfberhts, counterfeits were churned out like dubious Rolexes. There’s a documentary on Youtube about the staggering amount of effort put into making these swords, topped by a striking signature hammered into the blade – one slip and the sword was ruined. However, if you didn’t fork out for the British Museum’s £4.50 audio guide, you’d have walked past the swords without the slightest idea what they were.

It’s always good to see the lives of women represented, especially when it’s not limited to the domestic. We loved the section on sorceresses. These women possessed the gift of prophecy and were feared and respected in equal measure, making their grave goods particularly fascinating. Although the spiritual practices of different Viking settlements varied, there was a widespread belief in shapeshifting. Men turned into bears and wolves, but women’s spirits were allied to more furtive creatures like birds and fish, offering an interesting window into the Viking gender divide.

Near the sorceresses’ wands and finery, there was a tiny statue of a figure wearing female clothing, but labelled as ‘probably’ Odin nonetheless. This made us wonder if (much like female skeletons found buried with weaponry and consequently classified as male) we’re projecting our own gender theory onto history for want of further context. As the Vikings were a largely oral culture, we’ll probably never know.

Speaking of skeletons, bones were displayed sparingly and to great effect. Turning a corner, visitors come across a pile of skeletons divested of their heads – an entire Viking ship’s crew, dumped in a mass grave in Weymouth. The bodies were laid out as they were found, sprawled, face-down, fingers missing, suggesting their hands weren’t tied before execution. We’ve all seen human remains in museums, but this was unusually visceral.

All this was fascinating – if you got close enough. Our major criticism was echoed by everyone we know who’s been to the exhibition: the overcrowding. Many of the smallest and most delicate pieces were by the entrance, creating a bottleneck of bodies. At times it was impossible to see exhibits, and most of the labels were placed below the cases, meaning only the visitors with the sharpest elbows could read them. I’m 6’1″, and I struggled. By the time the room opened up to reveal the breathtakingly gigantic Roskilde 6 ship, most visitors were too stressed to enjoy it.

I love The British Museum, but they should have known better than to cram people in like that. However, if you’re tall or determined, Vikings: Life and Legend is still on until the 22nd of June 2014.