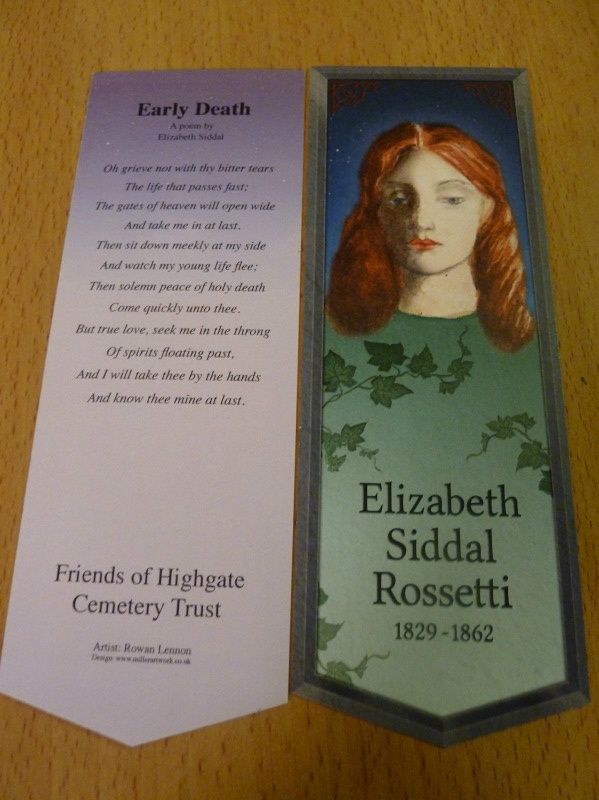

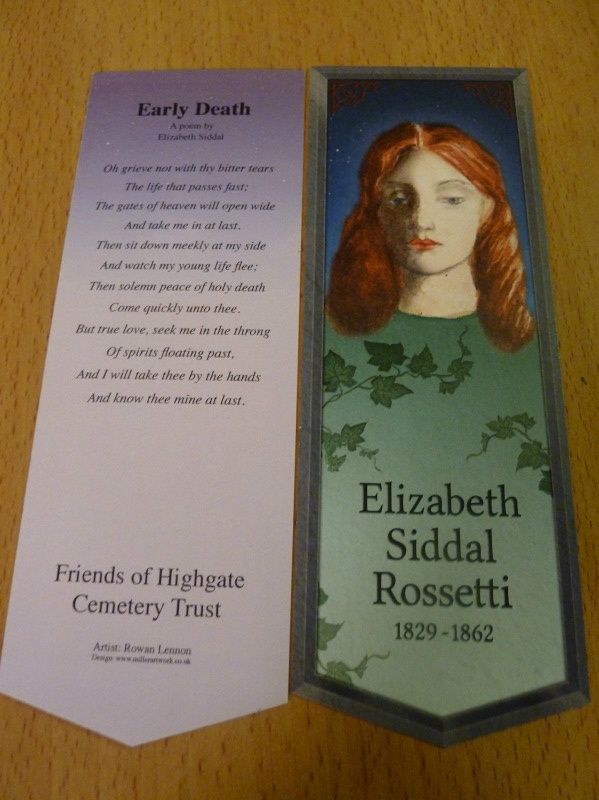

Yesterday, I travelled to Highgate cemetery for the 150th anniversary of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal’s death.

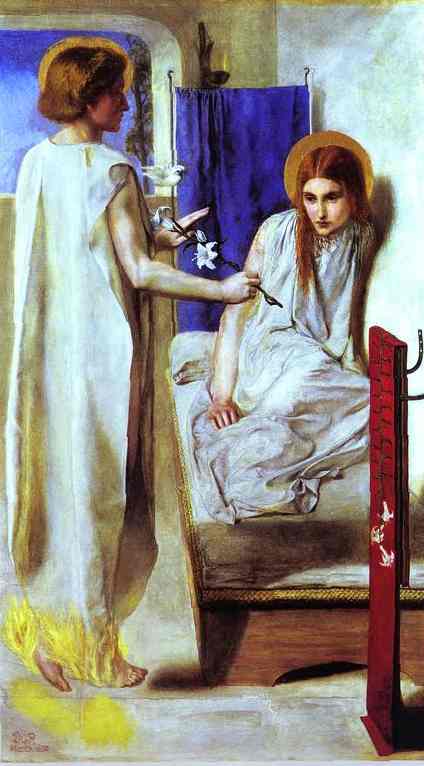

That morning, Lucinda Hawksley, author of The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel, and Jan Marsh, one of the leading lights of Pre-Raphaelite studies, laid lilies on Lizzie’s grave in the west cemetery. Being also the resting place of Christina Rossetti, they chose to read Christina’s In An Artist’s Studio, probably the most telling sonnet ever written about the iconic artist’s model:

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel — every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

That evening, in the sub-zero chill, Lucinda Hawksley gave a talk on Lizzie Siddal’s life and sudden death. For anyone who hasn’t had the pleasure of reading The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel (the publisher’s title, not Hawksley’s), there are few better ways to enter the world of The PRB. It’s an entertaining, thoughtful study of a fascinating period of artistic innovation, and, what’s more, it allows Lizzie Siddal the space to stand alone – not as a legend, but as a fully-formed human.

As is often the case with historical women, Lizzie Siddal has always been in danger of being overwhelmed by her own image. Even today, we’re told she simultaneously froze in Millais’ bathtub, killed herself after a blistering row with her husband, and slowly wasted away with Romantic Consumption™. Legend has it, she spent her life quietly enduring victimisation, and (conveniently for a stunner) never decomposed*. It’s saddening to see yet another woman artist and poet reduced to 2D, and it’s an especial problem with the Pre-Raphaelite sisterhood. Annie Miller is cast as the foulmouthed slut. Christina Rossetti is the religious one. Lizzie is relegated to a pedestal as The One Who Died. It is for this reason that it was so wonderful to spend yesterday with people who truly care about Lizzie and her legacy.

I first met Lucinda Hawksley a few years ago, while I was dissecting Lizzie’s poetry for my BA dissertation, and I was glad of the opportunity to see her again. She’s a charismatic speaker, and people always leave her talks smiling. Yesterday was no exception. In the newly-renovated Highgate chapel, she opened with the admission that she was glad to be talking about something other than her great-great-great-grandfather, Charles Dickens. With the recent bicentenary of his birth, Hawksley has been the guest-speaker du jour and she feels she’s rather Dickensed us to death. Hawksley’s talks manage to be rollicking fun. She has a way of putting the PRB humour back into what could be dry art history. When talking about Hunt being reviled for painting the holy family as Jewish: “As we know, Mary was from Sweden.”

The evening was full of the lovely anecdotes that flesh Lizzie out as the creative, funny, intelligent woman she was. How she silenced the bullies in her ladies’ art class by turning up in French fashions they could never hope to emulate; how she told ghoulish tales of her childhood neighbour, Mr Greenacre, who was hanged for dismembering his fiance; how she was shrewdly aware of her own image as a romantic figure, and embellished it with heightened depictions of her working-class upbringing. Lucinda Hawksley brings to the fore all those charming human elements of the PRB story that so often get swept away in the myth-making. As silly as it may sound, by the end of the evening, there was a warm sense of shared energy in the room, as if we were being told stories of someone we had all once known and loved.

The talk took place in the newly refurbished chapel, which, until recently, was in dire need of repair. Now, it’s an optimistic, bright space. Highgate is sadly neglected when it comes to funding, relying heavily on volunteers despite being one of the most beautiful places one is ever likely to see. The whole Highgate cemetery area is quiet and green – very ‘un-London’. It’s always a surprise to catch a glimpse of The Gherkin in the polluted horizon. I wonder if Lizzie would be pleased to know her body rests in such a peaceful spot. Christina, I’m sure, would be relieved. “O grave, where is thy victory?”

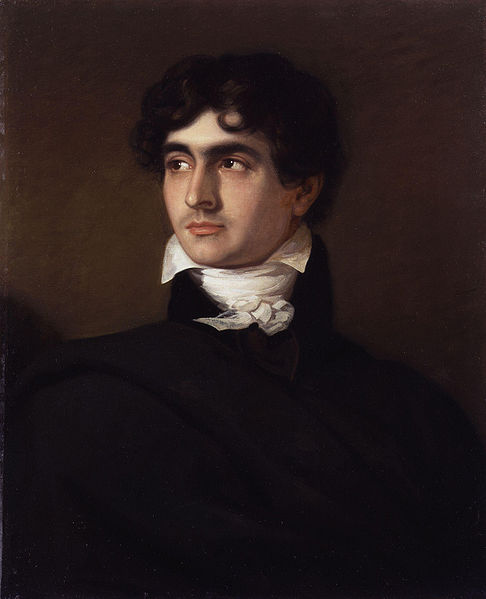

Although she was at the cemetery in the morning, Jan Marsh wasn’t able to make it to the talk, which is a shame, as I’d love the opportunity to tell her how important her writing has been to me. On a personal note, Dante Gabriel Rossetti is my absolute overwhelming passion. Even after a BA and an MA, with a PhD on the backburner, it’s difficult for me to talk about him and his work without becoming insufferable. I once turned a corner in the Fitzwilliam museum to find Rossetti’s 1882 Joan of Arc, and promptly had to pivot and faint on a bench. (Apparently, Stendhal syndrome does exist). He’s important – I’ll leave it at that.

Was Lizzie’s death a suicide? I’m unconvinced. But moreover, I don’t believe it’s the detail we should fix Lizzie’s life around. Yes, she died young and she died troubled, but she left an indelible imprint on British art and aesthetics. She was a skilled satirist and frequently reduced Algernon ‘sado-masochism’ Swinburne to giggles. She was a quick learner and impressed the major artistic players of the day, not as a novelty, but as a figure in her own right. She delighted in collecting the Oriental china the Aesthetes were so wild about. Her Christian faith was important to her. She was human.

Overall, it was heartening to see so many people gathering together yesterday to honour Lizzie by keeping a more accurate image of her alive, even after all these years. As one of the talk’s organisers reassured me as we prepared to step out into the snow: “We look after her”.

*Turn to the late Ken Russell’s hilarious Dante’s Inferno for zombie-Lizzie rising from her coffin and Oliver Reed as Rossetti scrambling across boulders to escape.

The new Highgate Cemetery website is soon to launch, with a list of upcoming events. I highly recommend becoming a member of the society, not only because funding is vital to the cemetery’s survival, but because the newsletters are a taphophile’s dream.