I have difficulty with Dickens.

I acknowledge the fact that he’s arguably the supreme symbol of the Victorian age I love so much, and yes, I adore his description of Miss Havisham’s rotting wedding cake. Say ‘speckled-legged spiders’ out loud. It’s beautiful. There are many things to like about Dickens, and I know it. But…

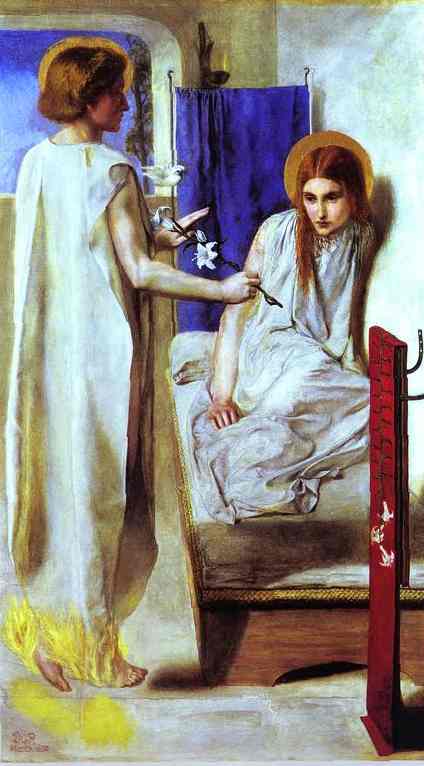

1) He was catty towards the Pre-Raphaelites and then retracted his statements as soon as they were popular, in that “I was at all their early gigs” way. Millais may have forgiven him, but I never will.

1) He was catty towards the Pre-Raphaelites and then retracted his statements as soon as they were popular, in that “I was at all their early gigs” way. Millais may have forgiven him, but I never will.

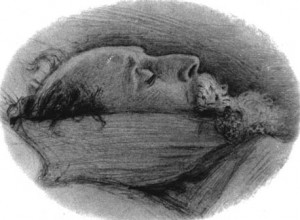

And 2) My parents took me to Dickens’ house in Portsmouth when I was small. Dad had me sit on the deathbed.* There was a big rip in the upholstery with the stuffing pouring out like guts, and I remember being convinced that Dickens had died thrashing and tearing at the velvet with his fingernails like some hairy roaring beast. Worse was the fact that the courtyard outside the room had recently suffered some kind of paint spillage. Nice, wet red paint. To this day, I have to remind myself during cosy Christmas BBC productions of Great Expectations that no, Charles did not throw himself out of any windows.

I don’t hate him, or especially dislike him. I just have trouble with him. And it turns out, my beef with Dickens may run in my family.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin of Quackery

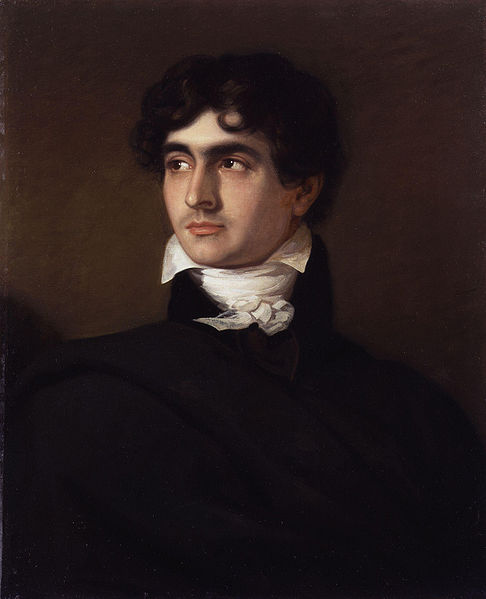

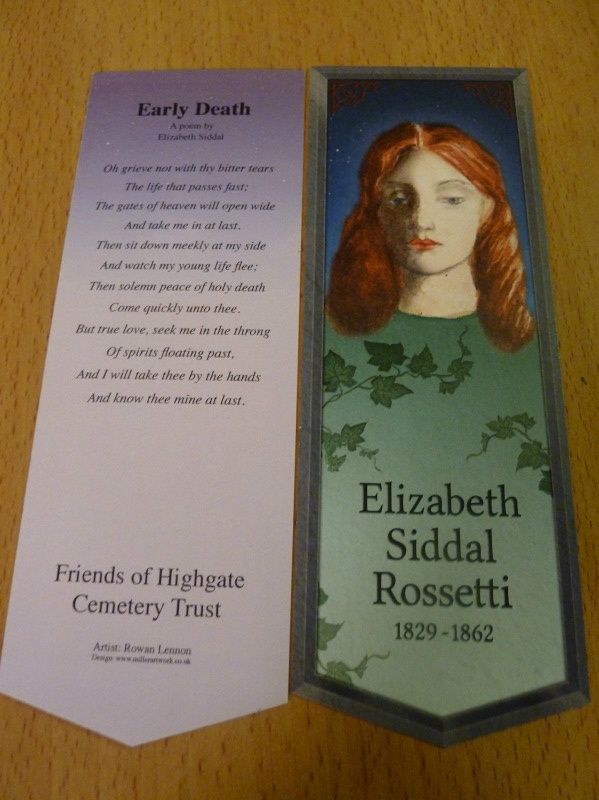

While my favourite Victorians painted and wrote and exhumed their dead wives, my great-great-great uncle made his fortune selling pills and ointments and then advertising to the point that there were few countries in which you could avoid him. ‘Professor’ Thomas Holloway (although he was as much as professor as I am a raccoon) was a businessman who never missed a trick, a man of strong opinions. It was said that “millions who have never heard of Napoleon … have heard of Holloway”.

While my favourite Victorians painted and wrote and exhumed their dead wives, my great-great-great uncle made his fortune selling pills and ointments and then advertising to the point that there were few countries in which you could avoid him. ‘Professor’ Thomas Holloway (although he was as much as professor as I am a raccoon) was a businessman who never missed a trick, a man of strong opinions. It was said that “millions who have never heard of Napoleon … have heard of Holloway”.

We Holloways are generally seafaring people. My dad spent 35 years in the Navy, his granddad did, and his dad in turn. During the eighteenth century, there was a patch in which thirteen of us had a go at petty crime and ended up being deported to Australia. On the same ship. So yes, we’re very nautical. Not so Thomas Holloway. Growing up in a Penzance pub, Thomas began concocting general-purpose ointments in the family kitchen in the late 1830s. Thirty years later, he was a multi-millionaire and living on a 72-acre estate that would later belong to John Lennon.

Like Dickens, Holloway rose to become one of the Victorian leviathans. Until recently, I had no idea whether the pair met, or even took much notice of each other. So I’m grateful to my friend Thora for pointing me to this article on The Quack Doctor detailing an amusing alleged incident between Holloway and Dickens…

The Professor, audacious in pursuit of a deal, supposedly sent a substantial cheque to Dickens in the hope of persuading him to highlight his ointments and pills in Dickens’ next novel. Product placement. What followed was a bitchy rebuff from one Enormous Victorian to another. It’s a brilliant piece of gossip, and I recommend you go and read it.

May Contain Traces of Nothing

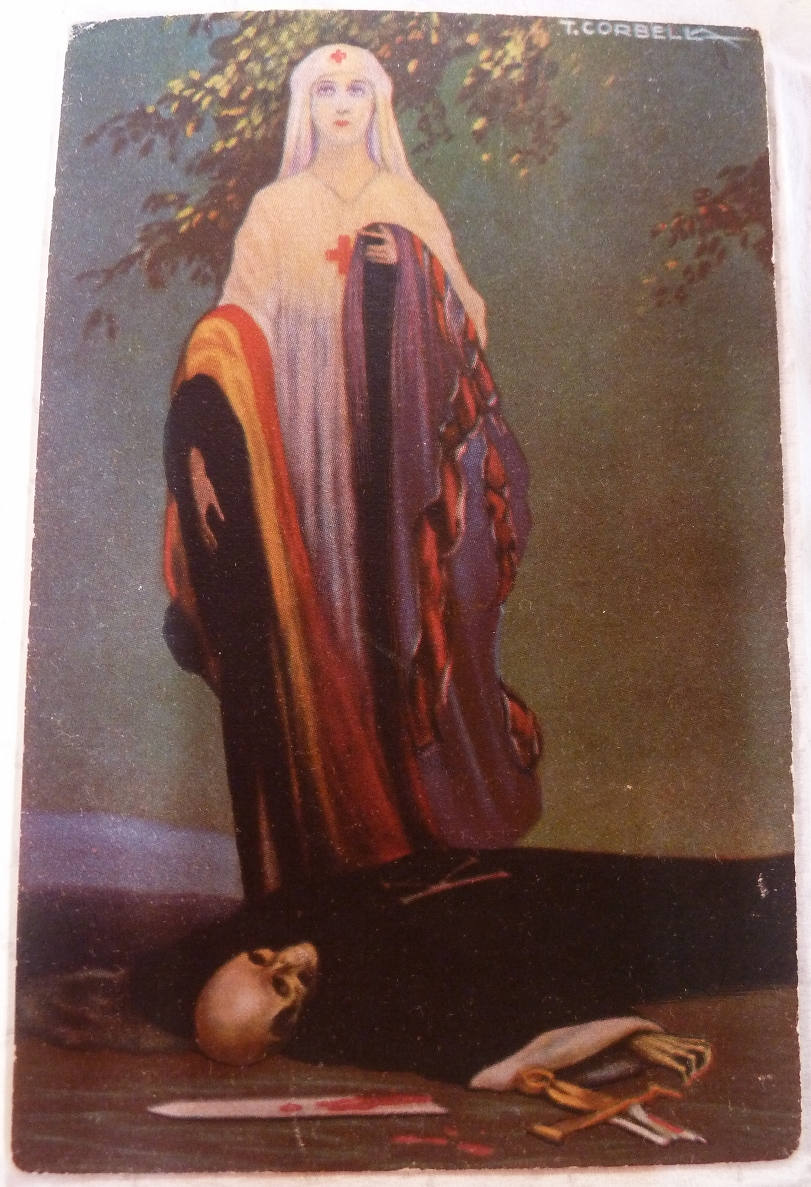

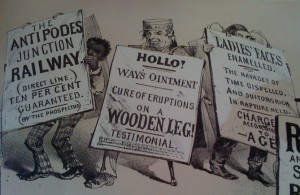

I have a small collection of Holloway’s ceramic ointment pots and advertisements. They promise ‘all good nurses’ rely on Holloway’s products, which is just as well, as his pills promised to cure everything from bronchitis to gout, period pain to fistulas. These were the days before advertising standards, when you could legitimately publish an ad asking DO YOU WANT YOUR CHILDREN TO DIE?

I have a small collection of Holloway’s ceramic ointment pots and advertisements. They promise ‘all good nurses’ rely on Holloway’s products, which is just as well, as his pills promised to cure everything from bronchitis to gout, period pain to fistulas. These were the days before advertising standards, when you could legitimately publish an ad asking DO YOU WANT YOUR CHILDREN TO DIE?

Thomas Holloway’s advertising was ruthless. If he were alive today, he’d be the mastermind behind those impossible-to-avoid “lose 2st with this implausible old tip” ads. Dickens commented on this in Household Words, joking at how terrible it would be to have psychological baggage attached to pills and ointments – Holloway’s posters were so ubiquitous, the victim would never escape their torment.

The trouble with Holloway is that, like Dickens, I don’t know how to feel about him. I admire his rise through society, but the medicine itself was pure fluff. Being a chronic invalid myself, I can’t shake the suspicion that The Professor brought down a karmic curse upon the family after all those years of fooling nannies into feeding their poorly charges something about as nutritious as Smarties. Deciding whether he was a goodie or a baddie all hinges on whether or not he knew it was fluff, and, unfortunately, he did.

It’s like that episode of Armstrong and Miller where Armstrong goes on Who Do You Think You Are?, and it turns out that each and every one of his ancestors were whores.

Although Thomas was aware his medicine was fluff, he claimed that the hundreds of letters he received from happy customers were all he needed in the way of proof he was doing good. His understanding of the placebo effect was pretty advanced, and he seemed never to view his customers as chumps.

So not dastardly exactly. She says. Hopefully.

As a philanthropist, at least, he was a good egg. He gave around one million pounds to charity and founded the uber-gothic Royal Holloway College for women which one of these days I’ll get around to claiming as my ancestral home. Considering it took until 1948 for Cambridge to grant full degrees to women, that was quite a progressive decision on face value.

As a philanthropist, at least, he was a good egg. He gave around one million pounds to charity and founded the uber-gothic Royal Holloway College for women which one of these days I’ll get around to claiming as my ancestral home. Considering it took until 1948 for Cambridge to grant full degrees to women, that was quite a progressive decision on face value.

But that’s all business. On a human level, he’s hard to pin down. As someone who deals in fiction, achievements don’t mean as much to me as characteristics. I have only snippets, like how, in the early days, he and his assistant would celebrate making a new batch of pills by having a good sing-song. His personal motto was “nil desperandum”. He worked hard, even on Christmas Day. From the few personal letters I’ve read, I can certainly say he was funny, but tending towards the melancholy. Like the rest of us Holloways, he was over six feet tall. He had a magnificent quiff.

This Isn’t Over, Charles

So did the snub actually happen? Leslie Katz’ paper “Dickens and Product Placement: Did He Refuse an Offer from ‘Professor’ Holloway?” concludes ‘probably not’. The story came from notorious fibber and owner of the gossip paper The World, Edmund Yates (What? A Victorian? Making something up?) after both parties had died. Although it’s a stunt The Professor was forward enough to try, there’s no proof that he did.

Which is a shame, as The Professor could be pretty catty himself, and the fallout would have been hilarious. Paraphrasing his estimation of William Makepeace Thackeray:

“That Mr. Dickens may think himself a very clever man; but I fancy that I could buy him up, ten times over.”

* Come to think of it, I doubt I sat on it. But in my traumatic memory, I was basically made to rub my face on Dickens’ hairy death-sofa.

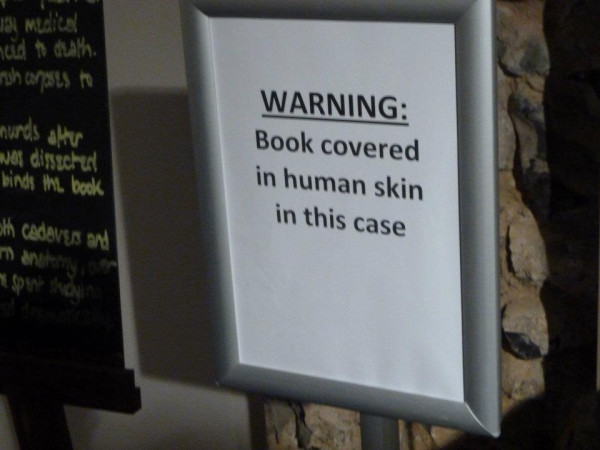

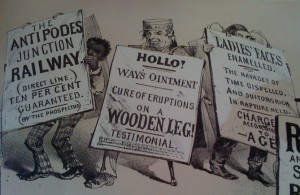

The pictures: At an antiques market, I came across the satirical poster shown above. The coin (a gift token) is stamped with Thomas’ bequiffed profile and was a present from my dad.