1840s Essex was a tough place to call home. If the damp cottages or the Potato Blight didn’t kill you, your wife might take the hump and lace your porridge with deadly poison.

This is the grisly focus of the new true crime book by Helen Barrell, Poison Panic: Arsenic Deaths in 1840s Essex.

Three ordinary Victorian women – Sarah Chesham, Mary May and Hannah Southgate – all stood trial, accused of poisoning with arsenic. The press quickly seized the stories, suggesting the women were part of a ring of murderesses who taught nice English housewives how to kill. The public were thrilled and repulsed. Was the average woman secretly capable of such a thing? And as this practically undetectable powder was freely available, what was stopping other women from sprinkling arsenic on their husbands’ dinner?

Three ordinary Victorian women – Sarah Chesham, Mary May and Hannah Southgate – all stood trial, accused of poisoning with arsenic. The press quickly seized the stories, suggesting the women were part of a ring of murderesses who taught nice English housewives how to kill. The public were thrilled and repulsed. Was the average woman secretly capable of such a thing? And as this practically undetectable powder was freely available, what was stopping other women from sprinkling arsenic on their husbands’ dinner?

I’ve talked to Helen about death and domesticity in 1840s Essex…

What drew you to poisonings as the subject of your first book?

I grew up reading Arthur Conan-Doyle and Agatha Christie, so when I tripped over a real-life poisoning case, I was fascinated. I had been transcribing the burial register for Wix in Essex, as part of my genealogical research, and there it was – some poor chap who’d been poisoned by arsenic. As a lot of my family are from that area, there was a chance that I was related to him, and so I started to dig deeper. With the British Newspaper Archive, there’s so many newspapers digitised and easy to access, so I was able to read the inquests and trials. Being a genealogist, I was able to reconstruct the families of the women who were accused of the poisonings, which is a new angle that hasn’t really been explored before.

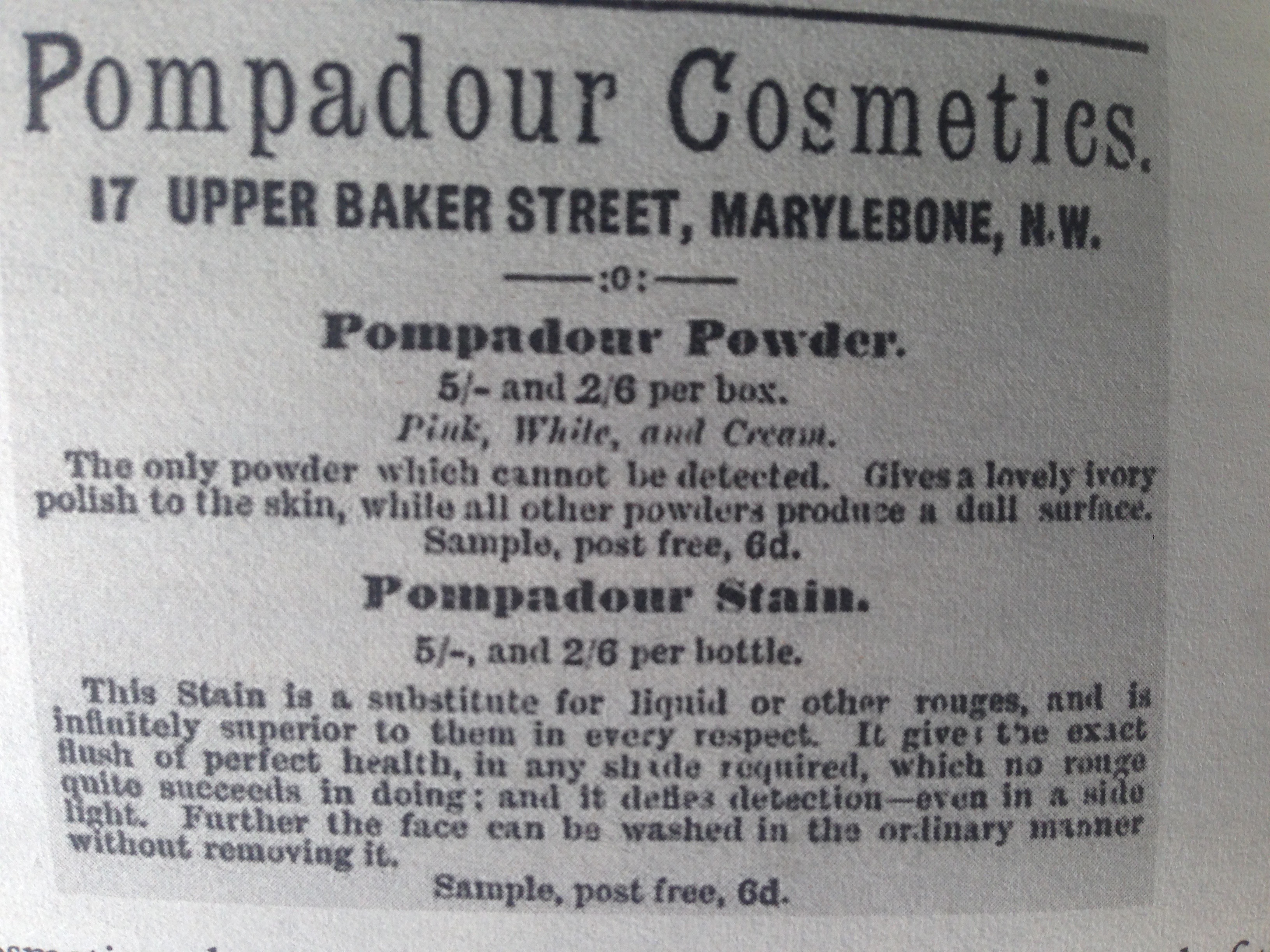

Arsenic poisoning is a terrible way to die, but that didn’t stop Victorians from using it around the home. Of the many 1840s uses for arsenic – disposing of a bad husband aside – which struck you as the most alarming?

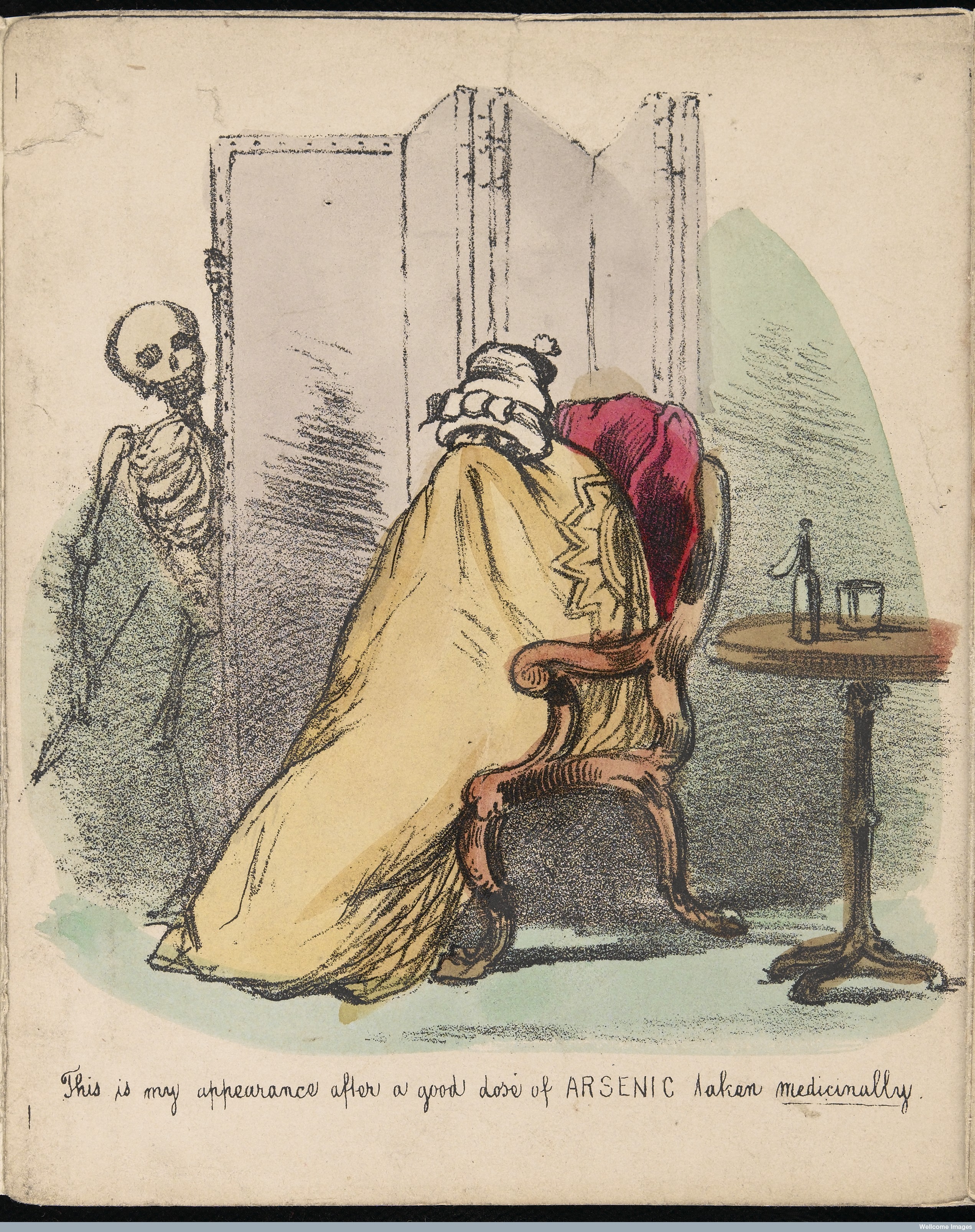

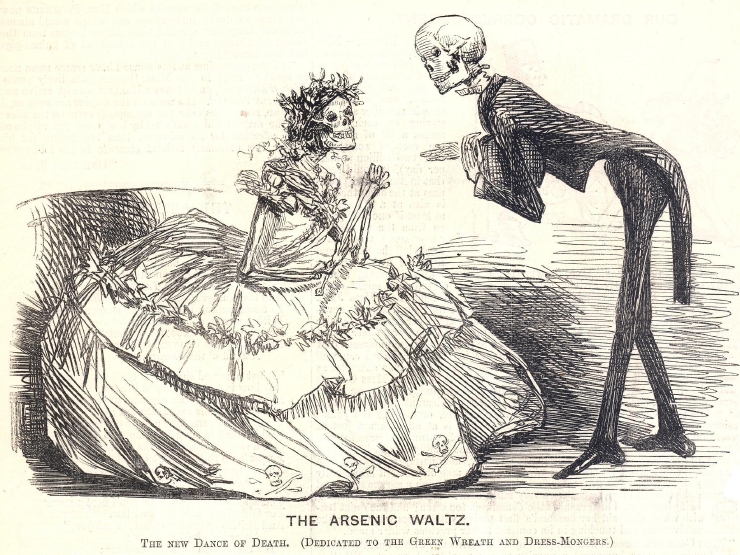

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

But I think what shocked me most was how casual they were about using arsenic in conjunction with food. You could become poisoned by it if you absorbed it through the skin, but the most common way was by it entering your mouth. So if you’re trying to deal with rodents plaguing your badly maintained cottage, putting arsenic on bread and butter to attract the vermin might seem like a good idea. But if you’ve got a house full of people, it’s just possible that someone might accidentally die. Especially as arsenic used in the home was often ‘white arsenic’ and resembled flour.

What alarmed me more, though, was that arsenic-based green dyes (Scheele’s Green) were used in food colouring. And yes, it killed people. In 1853, two children died eating the green ornaments on their Twelfth Night cake, and in Northampton in 1848, one man died and several others fell ill after eating a green blancmange. The shopkeeper who sold the dye for the blancmange was convicted of manslaughter – why? Because it was felt he hadn’t explained the safe dose clearly enough.

“He’s in the burial club” was Victorian slang for ‘he’s not got long to live’. Tell us about these these burial clubs and how they tied in to the 1840s poison panic.

I’m sure you’ve heard of the case of Burke and Hare, the Edinburgh-based resurrection men who, rather than dig updead bodies, killed people to provide Edinburgh Medical School with cadavers. Following that scandalous case, it was decided that Something Must Be Done. As long as it didn’t involve dead middle- and upper-class people being cut about by medical students; after all, the faithful believed that an anatomised body couldn’t rise from the grave on Judgement Day (though somehow bodies reduced to bones and dust could). So Edwin Chadwick, that enemy of the poor, came up with a brilliant plan. How about parishes, which were more or less the local councils of their day, selling their dead paupers to medical schools when they were in need of a body. So if you died, and your body was unclaimed by family and friends because they couldn’t afford to bury you, you could end up the subject of an anatomy lesson – the poor weren’t allowed agency over their own bodies.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

Except burial clubs were run by self-organising workers, usually meeting in pubs. So for instance, in Great Oakley in Essex, you had the Maybush Burial Club, which met at the Maybush pub – that pub is still open. Landlords liked to get involved as they could convince the funeral party to have a knees up at their pub. But they weren’t very secure, and they were unregulated, which meant that you could pay into a club for several years, and then when Little Eleazar went the way of all flesh, the club has packed up and can’t payout. So people would enter family members in more than one club at once. But then there was a problem – what happens if the clubs are in fine fettle when Little Eleazar’s cough turns bad, and you get a £10 payout from four different clubs? You’ve suddenly got £40 from your son’s death. Edwin Chadwick decided that some parents were entering children in multiple clubs and then murdering them, just for the burial club money. It’s a version of the life insurance murder, which would reach its most infamous moment at the trial of William Palmer in 1856.

Mary May, who lived in Wix, had entered her half-brother William Constable (also known as Spratty Watts), in a burial club in Harwich. He died a month later. The local vicar, Reverend George Wilkins, was suspicious, especially as Mary kept pestering him to write notes for the burial club, as they wouldn’t pay out. There was an inquest and it was discovered that Constable had died of arsenic poisoning. But had Mary May really murdered her own brother for £10?

In the 1840s, how could an investigator attempt to detect arsenic in a suspected poisoning case? How accurate were these early forensic techniques?

I’ve been doing lots of research into this for my second book – it’s quite interesting. Sometimes the investigator would be able to see arsenic with the naked eye: either in white lumps, or yellow orpiment. This was caused by arsenic oxide (white arsenic) reacting with the sulphur being released in the body after death, creating arsenic trisulphide. In one case, Professor Taylor asked one of the illustrator at Guy’s Hospital, where he worked, to produce a colour drawing of the deceased’s stomach, and use the arsenic trisulphide with gum to show where he had found the poison in the body. Not quite something you’d see in a courtroom now, but I suspect Taylor would’ve embraced colour photography if it had existed in his lifetime.

They would also look for backup evidence – the symptoms of poisoning were important, partly to indicate what they had been poisoned with, but the onset of symptoms would indicate when the poison had been administered, and might point you in the direction of the culprit. It could even lead you to realise it was an accident. But then you had the problem that poisoning symptoms, such as those of arsenic, weren’t unlike the gastric upsets that were common in a world with poor sewerage systems. It just wasn’t possible to open an inquest for everyone who died of violent vomiting and diarrhoea, as it would upset the county ratepayers who footed the bill for Professor Taylor.

In the early 19th century, they had to rely on a battery of tests. In some forms, arsenic would smell of garlic when it was heated, but this was clearly unreliable as it relied on the chemist’s sense of smell. There was the reduction test, which was a bit more reliable, but you needed to have a decent about of arsenic present for it to work. You heated arsenic oxide (white arsenic) in a tube, which released the oxygen and turned it into a metal. If you were testing a liquid, you used hydrogen sulphide to make arsenic trisulphide. The remaining oxygen reacted with the hydrogen and created water, then you could perform the reduction text on the arsenic trisulphide. There were reagent tests as well, which relied on the known reactions of arsenic with other chemicals, but they were unreliable when there was, how shall I put it, organic matter present, which would affect the colour changes.

So in 1836, James Marsh came up with a test involving hydrogen and zinc, which forced arsenic out of liquids. You’d hold a piece of cold glass over the end of the tube and as the highly poisonous ‘arsenuretted hydrogen’ (or arsine gas to you and I) came out, the arsenic would deposit itself on the glass in a convenient metallic film. You could then use the reduction and reagent tests on the metallic film; the test would also dislodge other poisons such as antimony and mercury, so you had to rule those out.

In the early 1840s, Hugo Reinsch’s test took over from Marsh’s. It used simpler equipment – you added hydrochloric acid to your suspicious liquid, and dipped in some copper. Any arsenic present would appear on it, again, as a metallic film, and the other confirmatory tests could be performed.

The Marsh and Reinsch tests were far more sensitive than the previous methods available, but this could lead to embarrassing mistakes, such as eminent French chemist Orfila claiming that arsenic was a natural constituent of human bone. When he used the Marsh test on bone, a metallic film resulted, but far too small for him to carry out any confirmatory tests. It’s possible that the arsenic found in the alleged victim of Madame Lafarge, which Orfila used the Marsh test to investigate, actually came from the pots his corpse was boiled up in, or the acids that were used as part of the process.

If you’re dealing with someone who’s been killed with a large dose of arsenic, the Marsh and Reinsch tests are probably quite reliable – as long as the chemist has checked their apparatus, their zinc, and copper, and acids for any contamination. But it’s when the amounts are small that there’s a problem and it seems less reliable. When Sarah Chesham’s husband died, Taylor found a tiny amount of arsenic inside him – in 1859, he wrote that it was the smallest amount he’d ever identified. But he was clear with the prosecutors – it was too small an amount for Sarah to be charged with murder. Bearing in mind the problem he ran into later in 1859 with the Smethurst trial, I have to wonder if the arsenic Taylor found in Richard Chesham’s insides was from Taylor’s laboratory apparatus, rather than a dose administered with murder in mind.

How did the press handle the idea of women murdering their husbands? Do you think Southgate, May and Chesham’s cases would be approached differently by today’s tabloids?

The first thing that struck me about the way they reported the cases was how they described the accused. These days, people in news stories are described as ‘mother of two’ or ‘a grandmother’ – and the same goes for how they describe men, even if the news story that follows has no bearing on whether or not they’ve managed to reproduce! Anyway, in the 1840s, the newspapers would define you by your social status. So the women in Poison Panic, the women were described as ‘wife of an agricultural labourer’ or ‘wife of a farmer.’

And then there’s the women’s appearances. When women were found not guilty, the newspaper describes them as beauties, and women sent to hang are described in highly unflattering terms. At the execution of one of the women in Poison Panic, the papers commented on the fact that her stoutness meant her hanging was swift; it seems such an unseemly thing to comment on, but it’s an extra indignity piled onto an already wretched end. Newspapers still make a big fuss about women’s appearances, more so than men’s.

Victorians adored a good murder. How did these sensational crimes filter down into the popular culture of the day?

Public executions drew big, rowdy crowds, so if you wanted to make some money, just print up some doggerel verse with the name of the condemned shoved in any old how. It doesn’t even have to rhyme that well, and it certainly doesn’t need to scan. It wasn’t unusual for people to use execution ballads as their newspapers, as some were sold house-to-house, or in the streets, which is problematic as the ballad-sellers didn’t make much attempt at factual accuracy.

If there was a particularly sensational trial – such as that of Thomas Drory, the Essex farmer who strangled his heavily pregnant lover – the ballad-sellers really went to town. You could buy an illustration of Drory murdering Jael Denny; you know he’s bad because they gave him a melodrama villain’s mustachios. What a lovely souvenir.

Executions had previously taken place only a couple of days after sentence was passed, so there wasn’t much time for them to prepare their ballads. As one ballad-seller explained to Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor, “There wasn’t no time for a Lamentation; sentence o’ Friday, and scragging o’ Monday.” But by the 1840s, there would be several weeks before the hanging, so they could print multiple confessions, lamentations, and ‘true histories’ (which were anything but), ensuring that it wasn’t just William Calcraft who earned a pretty penny from a hanging. Sorry, ‘scragging.’

You’ve invested in a pretty fantastic Victorian outfit. Can we hope to see you out and about in it?

I’ve always loved dressing up in historical costume, probably because I was taken to Kentwell Hall at an impressionable age! So when the chance came up to have my own made-to-measure 1840s dress, it had to be done.

I’ve been a fan of the Brontës for a long time, and at one point was considering a postgrad research project on them. I’d been researching the 1840s, which is another reason why finding that burial record from 1848 was somewhat fortuitous! And seeing as it’s the 200th anniversary of Charlotte Brontë’s birth – which, I feel I must say, has been overshadowed by the anniversary of that playwright bloke’s death – getting my bonnet on seemed only right.

I shall indeed be scuttling about in it; quite frankly, whenever the opportunity arises.

And finally, tell us about your work in progress, Fatal Evidence.

And finally, tell us about your work in progress, Fatal Evidence.

The name “Alfred Swaine Taylor” runs through Poison Panic like “Clacton” through a stick a rock. He’s the expert witness in nearly all the cases in my book, and although he’s mainly remembered as a toxicologist, he was involved in the Drory case because he identified bloodstains on clothing, and could comment on strangulation. He gets called ‘the father of English forensic science’ quite often, as well he might, but no one had written a book-length biography of him. So Fatal Evidence is a balance between Taylor the public man, in his laboratory and in the witness box, and Taylor the private man, in his home in Regent’s Park, borrowing his wife’s lace to experiment with photography. It’s fascinating – all the different cases he worked on, and all the ridiculous things scientists did then. Taylor only became Professor of Chemistry at Guy’s Hospital because his predecessor accidentally blew himself up when experimenting with compressed gas, and Taylor’s Scottish counterpart, Robert Christison, found out that arsenic didn’t really have a flavour by putting it on his own tongue! That will be published next year – I’ve already started looking for a cravat.

Poison Panic is published by Pen & Sword at the end of June, and available for pre-order now.

Shop on Amazon UK, Amazon US and iBooks for what the Pope himself* has called “a really excellent slice of sacrilege and apocalypse”.

Shop on Amazon UK, Amazon US and iBooks for what the Pope himself* has called “a really excellent slice of sacrilege and apocalypse”.

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments.

It’s hard to know where to start, when you consider they were rubbing arsenic-infused preparations onto their faces, or wore clothes made with arsenic dye, or had wallpaper coloured with it. It was taken medicinally in Fowler’s Solution – tiny amounts of it gave people a pep, and in fact, it has a positive effect on the blood, hence it’s used today in leukaemia treatments. At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

At the same time, you’ve got funerary and mourning rituals becoming increasingly codified – the Victorians loved a good funeral, and it was a point of pride to give your loved ones a good send off. For a few pence a week, you could sign up your loved one to a burial club, so that when the time came for the solemn bell to toll for them, the burial club would pay out – about £10, which in the late 1840s was half a year’s wage for the average East Anglian farm worker. You’d have a respectable funeral and avoid medical students laughing at your embarrassing wart. Sounds like a win-win situation.

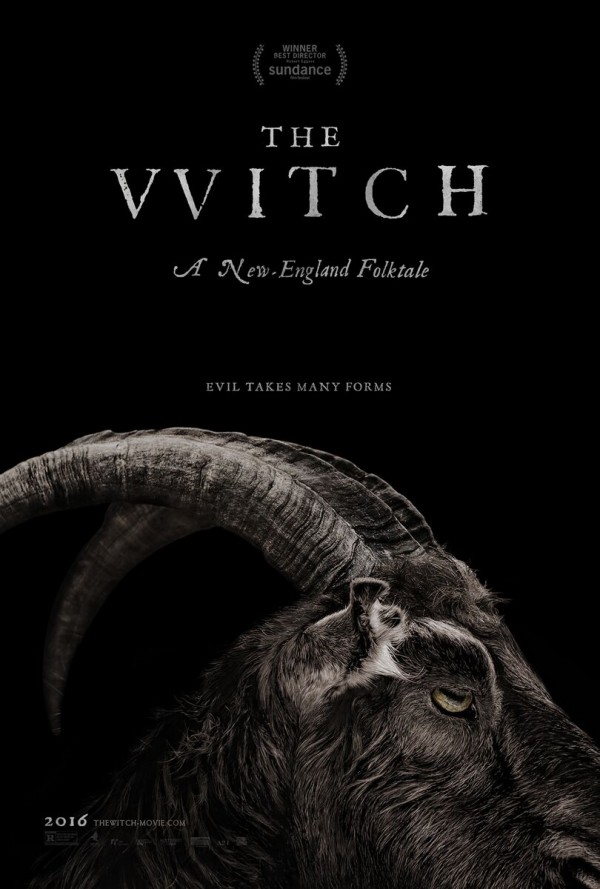

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of

Amid all the jolly goat-related devastation, some scenes reminded me of certain folk tales and cases of bizarre phenomenon I’ve taken to my heart over the years. In the spirit of