The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

The first rule of Dennis Severs’ house is that you do not talk in Dennis Severs’ house.

Not that you’re given a chance to say anything. As we rounded the corner into Spitalfield’s Folgate Street and rang the bell on number 18, the door immediately opened to reveal a composed gentleman in warm winter clothes.

“Is this your first visit to my friend Dennis’ house? Entry is ten pounds. I warn you, there is a mad cat.”

What were we in for? The Californian Dennis Severs moved into Folgate Street in 1979, when the run-down area was attracting colourful types like Gilbert & George. Bypassing frivolities like electricity and modern plumbing, he decorated each of the house’s eleven rooms in the style of a different era, from 1724 to 1914. The aim, or ‘game’ as he put it, was to give the impression the original occupants of the house – the Jervises, a family of Huguenot silk weavers – had just left the room.

Ring the bell, hand over your tenner, and slide into the past.

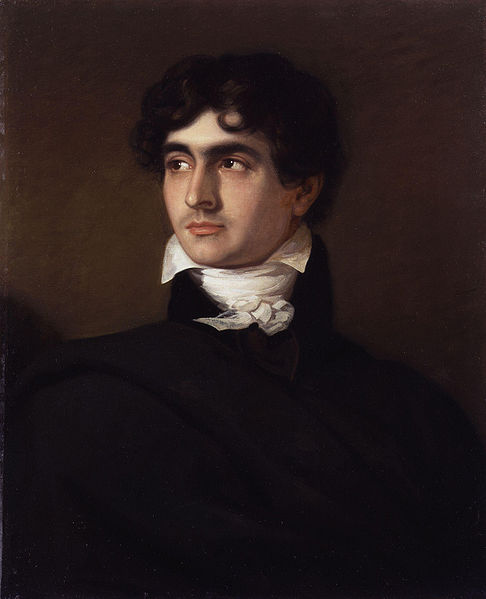

Photograph by Roelof Bakker

The motto of the house, Aut Visum Aut Non (‘you either see it or you don’t’), hints at the ghostly quality of the place. Severs died in 1999. In his Will, he asked the house be kept as it was during his lifetime, still admitting the curious, silent public.

Inside the tall, dimly lit house, you see no ghosts. But you hear them, oh yes. The atmosphere is an entity in itself, following you, touching you. You learn to minimise your movements to avoid the naked flames. You tune into the language of the nibbled scone, the glistening yolk of a cooling boiled egg, the afternoon sherry guiltily abandoned. Upstairs, in the paupers’ room, the collapsing ceiling admits sighs of freezing London air.

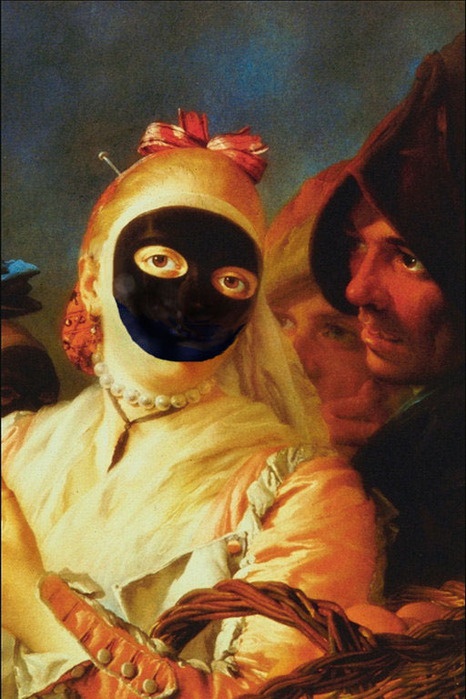

“Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.”

Performance art of this kind offers strange intimacy. I was reminded of Punchdrunk’s incredible 2007 production of The Masque of The Red Death in which the audience were given masks and let loose in the industrial cavern that is Battersea Arts Centre. You could rifle through tattered paperwork, watch contortionists getting violently busy on a four-poster bed, or enter a mad puppet show…but you had to remain silent.

In my mask, I laid eyes on a boy (man? It was so dark, I couldn’t tell), taller than me – rare, as I’m over six foot – lurking in a chamber of piled silks and wools. He beckoned; I unthinkingly obeyed. Without permission, he laid a velvet cloak around my shoulders and slowly fastened the clasp. Was he gorgeous? I don’t know; I never saw more than his eyes, which I stared into with inebriated fascination for far longer than was polite until he laid his hand on my back – a touch! – and moved me on.

That, I think, is the trick of performance art. Like a parasite, it knows your boundaries and wheedles inside. Think of Venetian prostitutes with their Servetta Muta masks held by a bit between the teeth. Anonymity is intimacy.

“Those in the past were also dizzy and dumbstruck”

Severs left a note for us in Mrs Jervis’ pink confection of a rococo dayroom. To experience the house without sensing the long-gone occupants would be “like celebrating the Millennium as a number, without Christ.” It’s safe to say he took his still life drama seriously. But that heavy statement was interesting…

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable.

“You must forgive the shallow who must chatter,” says another note. We have the Internet, 24 hour news, the telephone with the police on the end waiting for our call. The Severs house recreates the cut-offedness we’ve learned to forget. If you love history, you spend eons inside books offering first person accounts of a moment 100 years old or more, but when you enter the closed atmosphere of 18 Folgate Street, with its strange sounds, strong smells, and unreliable light, you at once feel vulnerable.

But the house is merely a pretty illusion if you aren’t willing to let down your barriers – a fact brought home by the frequent smacks on the wrist in the form of signs saying, “STOP LOOKING AT INDIVIDUAL OBJECTS/ARE YOU STILL LOOKING AT THE OBJECTS/WELL STOP IT”. The spirit of the age was what Severs wanted to capture, not a cabinet of curiosities. These signs are more off-putting than the small anachronisms such as supermarket labels on the claret bottles. Besides, I like to think they were all part of the game. Where would Hogarth’s revelers get their cheap plonk if they were around today? Sainsbury’s, like the rest of us.

It takes an experience like 18 Folgate Street to illustrate how different we are to our ancestors – and how viscerally similar.

As Severs said:

“You are 100 years old; you are wise.”